Università Di Pisa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Birth of Funk Culture

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture Domenico Rocco Ferri Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ferri, Domenico Rocco, "Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture" (2013). Dissertations. 664. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/664 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Domenico Rocco Ferri LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO FUNK MY SOUL: THE ASSASSINATION OF DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. AND THE BIRTH OF FUNK CULTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY DOMENICO R. FERRI CHICAGO, IL AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Domenico R. Ferri, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Painstakingly created over the course of several difficult and extraordinarily hectic years, this dissertation is the result of a sustained commitment to better grasping the cultural impact of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and death. That said, my ongoing appreciation for contemporary American music, film, and television served as an ideal starting point for evaluating Dr. -

Brown Jordan FINAL W Signed

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I’d like to thank the English Department at UWO, especially Professor Laura Jean Baker, Dr. Stewart Cole, Professor Douglas Haynes, Dr. Ron Rindo, and Dr. Christine Roth, as well as former Professor Pam Gemin and Dr. Paul Klemp. Their encouragement went a long way. Additionally, Tara Pohlkotte and the regular group of participants at Storycatchers live events, where I read early versions of many of these pieces to attentive and empathetic audiences. I would also like to thank my fellow graduate and undergraduate students at UWO, as well as many of my personal friends, for reading drafts, offering feedback, and putting up with me and my many shortcomings. Especially Chloé Allyn, Adam Bartlett, Lyz Boveroux, Tanner Kuehl, and John Pata. Thanks to all of my parents, who got me as far as they could. It was a real team effort. Some of these pieces have appeared elsewhere: “Saturday Pancakes & Hash at Perkins” was printed in the Spring 2018 issue of Bramble Lit Mag. A different form of “Henry Wakes Up” was published in Issue 34 of Inkwell Journal, an excerpt of “Let’s Not Be Ourselves” appears in Issue 2 of Wilde Boy, and the full version of “Let’s Not Be Ourselves” appears, alongside work from many of my colleagues and friends, in the 2019 issue of The Bastard’s Review. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................... ii CRITICAL INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 1 HENRY WAIT ........................................................................................................ -

The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Birth of Funk Culture Domenico Rocco Ferri Loyola University Chicago, [email protected]

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture Domenico Rocco Ferri Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Recommended Citation Ferri, Domenico Rocco, "Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture" (2013). Dissertations. Paper 664. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/664 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Domenico Rocco Ferri LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO FUNK MY SOUL: THE ASSASSINATION OF DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. AND THE BIRTH OF FUNK CULTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY DOMENICO R. FERRI CHICAGO, IL AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Domenico R. Ferri, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Painstakingly created over the course of several difficult and extraordinarily hectic years, this dissertation is the result of a sustained commitment to better grasping the cultural impact of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and death. That said, my ongoing appreciation for contemporary American music, film, and television served as an ideal starting point for evaluating Dr. King’s legacy in mass culture. This work likewise is wrought from an intricate combination of support and insight derived from many individuals who, in some way, shape, or form, contributed encouragement, scholarly knowledge, or exceptional wisdom. -

45 Inventory

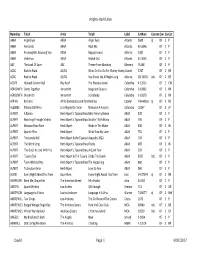

45 Inventory item type artist title condition price quantity 45RPM ? And the Mysterians 96 Tears / Midnight Hour VG+ 8.95 222 45RPM ? And the Mysterians I Need Somebody / "8" Teen vg++ 18.95 111 45RPM ? And the Mysterians Cryin' Time / I've Got A Tiger By The Tail vg+ 19.95 111 45RPM ? And the Mysterians Everyday I have to cry / Ain't Got No Home VG+ 8.95 111 Don't Squeeze Me Like Toothpaste / People In 10 C.C. 45 RPM Love VG+ 12.95 111 45 RPM 10 C.C. How Dare You / I'm Mandy Fly Me VG+ 12.95 111 45 RPM 10 C.C. Ravel's Bolero / Long Version VG+ 28.95 111 45 RPM 100% Whole Wheat Queen Of The Pizza Parlour / She's No Fool VG+ 12 111 EP:45RP Going To The River / Goin Home / Every Night 101 Strings MMM About / Please Don't Leave VG+ 56 111 101 Strings Orchestra Love At First Sight (Je T'Aime..Moi Nom Plus) 45 RPM VG+ 45.95 111 45RPM 95 South Whoot (There It Is) VG+ 26 111 A Flock of Seagulls Committed / Wishing ( If I had a photograph of you 45RPM nm 16 111 45RPM A Flock of Seagulls Mr. Wonderful / Crazy in the Heart nm 32.95 111 A.Noto / Bob Henderson A Thrill / Inst. Sax Solo A Thrill 45RPM VG+ 12.95 555 45RPM Abba Rock Me / Fernando VG+ 12.95 111 45RPM Abba Voulez-Vous / Same VG+ 16 111 PictureSle Abba Take A Chance On Me / I'M A Marionette eve45 VG+ 16 111 45RPM Abbot,Gregory Wait Until Tomorrow / Shake You Down VG+ 12.95 111 45RPM Abc When Smokey Sings / Be Near Me VG+ 12.95 111 45RPM ABC When Smokey Sings / Be Near Me VG+ 8.95 111 45RPM ABC Reconsider Me / Harper Valley p.t.a. -

Singles-David.Xlsx Namekey Titlea Artist Titleb Label Catnum

singles-david.xlsx NameKey TitleA Artist TitleB Label CatNum CommentsOwnerConditionCat ABBA Angel Eyes ABBA Angel Eyes Atlantic 3609 dj DF 1 P ABBA Fernando ABBA Rock Me Atlantic 45-3346 DF 1 P ABBA Knowing Me, Knowing You ABBA Happy Hawaii Atlantic 3387 DF 2 P ABBA Waterloo ABBA Watch Out Atlantic 45-3035 DF 2 P ABC The Look Of Love ABC Theme From Mantrap Mercury 76168 DF 2 P ACDC Back In Black AC/DC What Do You Do For Money HoneyAtlantic 3787 DF 2 RR ACDC Back In Black AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Atlantic OS 13235 btb DF 1 RR ACUFF Wabash Cannon Ball Roy Acuff The Precious Jewel Columbia 4-52014 DF 2 CW AEROSMITH Come Together Aerosmith Kings and Queens Columbia 3-10802 DF 2 RR AEROSMITH Dream On Aerosmith Somebody Columbia 3-10278 DF 2 RR AFRIKA Reckless Afrika Bambaataa and FamilyReckless Capitol P-B-44163 dj DF 3 RE ALEGRES Paloma Del Alma Los Alegres De Teran Novturno A Rosario Columbia 10147 DF 3 SP ALPERT A Banda Herb Alpert's Tijuana Brass Miss Frenchy Brown A&M 870 DF 2 P ALPERT Marching Through Madrid Herb Alpert's Tijuana Brass Struttin' With Maria A&M 706 DF 2 P ALPERT Mexican Road Race Herb Alpert Wade in The Water A&M 840 DF 2 IN ALPERT Spanish Flea Herb Alpert What Now My Love A&M 792 DF 2 P ALPERT The Lonely Bull Herb Alpert & the Tijuana BrassAcapulco 1922 A&M 703 DF 3 P ALPERT The Work Song Herb Alpert's Tijuana Brass Plucky A&M 805 DF 3 IN ALPERT This Guy's In Love With You Herb Alpert's Tijuana Brass A Quiet Tear A&M 929 DF 3 P ALPERT Tijuana Taxi Herb Alpert & The Tijuana BrassZorba The Greek A&M 8507 btb DF -

Here There’S a Wall : Jeffrey Francis Stanley Neumann Photography by Andrew Mcallister Text by Denny Fraser

2 3 4 PG 6 EDITORS NOTE PG 39 ARTIST OF ORIGINAL, AMERICAN & AUSTRIAN PAINTINGS: BERTHA HALOZAN TEXT BY HILLA KATKI PG 6 THE SELF TAUGHT TEXT BY DAN PRINCE PG 43 WHERE THERE’S A WALL : JEFFREY FRANCIS STANLEY NEUMANN PHOTOGRAPHY BY ANDREW MCALLISTER TEXT BY DENNY FRASER PG 16 THE SPIRIT OF ESTHETICS : DAVID LIVINGSTON HANSON PHOTOGRAPHY BY CASSANDRA MALLIEN TEXT BY DAVID LIVINGSTON HANSON PG 53 THE MESSAGE & THE SENDER : BUZZ BORON PHOTOGRAPHY BY ANDREW MCALLISTER TEXT BY BUZZ BORON PG 24 REAP WHAT YOU SEW : RAY MATERSON TEXT BY SARAH CLAPSADDLE PG 62 SLEEP OF REASON INTERVIEW WITH CHRIS MARS BY SAMANTHA KAINE PG 32 ART & SCIENCE : IONEL TALPAZAN PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRIAN ULRICH TEXT BY IONEL TALPAZAN PG 67 THRIFT ART PROJECT PARTICIPANTS BUY SOME ART WITH 20 BUCKS PG 37 THE KIDS COLLAGE PROJECT PG 74 AUDIO CD COLLAGES FROM THE CHILDREN’S INPATIENT UNIT THIS ISSUE’S ARTIST INTERVIEWS AND MUSIC FEATURES summer 2005 CONTENTS volume 1 issue 1 5 6 CONTRAPTION Growing up in the former rubber capital of the world, where the mercury levels in the water may have been a little too high and the struggles of family, friends, and neighbors were a little too visible, I found DESIGNER AND EDITOR myself surrounded by people who were compelled to express themselves creatively. My mother was Johnathan Swafford always drawing and crafting anything she could get her hands on. My father would blow on his trumpet for hours when he had been laid off from the factory. Maybe they were using expression to overcome personal difficulties. -

African American Vernacular English in the Lyrics of African American Popular Music

African American Vernacular English in the Lyrics of African American Popular Music Matthew Feldman 2 1.0 Introduction This thesisl investigates the use of grammatical features of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) in African American popular music from three different periods of the 20th century. Since the late 1960s there have been numerous studies of the language of African Americans, but none has attempted to use song lyrics as a major source of data. This is not entirely surprising. It would be a mistake to blindly equate song lyrics with other forms of language, for musical performance is a distinctive genre of language use. Nonetheless, as will be demonstrated below, the lyrics of songs produced by African Americans are a valuable source of information about AA VE. No source of linguistic data is free of limitations, so no potential source should be ignored. Studies of AAVE have been based on a variety of sources, including slavery-era literary texts (e.g. Dillard 1972), letters written by freed slaves (Montgomery, Fuller, and DeMarse 1993), transcripts of Depression-era interviews with former slaves (e.g. Schneider 1989), audio recordings of interviews with former slaves (Bailey, Maynor, and Cukor-Avila 1991), exam essays written by African American high school students (Smitherman 1992, 1994), and sociolinguistic interviews (e.g. Wolfram 1969, Labov 1972, Rickford 1992). Each of these sources is useful within certain contexts, yet their validity could still be challenged. The same is true of song lyrics. As with other potential sources, it is important that African American song lyrics are examined and that their strengths and weaknesses as sources of information about AA VE are recognized. -

The James Brown Soul Train Honky Tonk (Parts 1 & 2) Mp3, Flac, Wma

The James Brown Soul Train Honky Tonk (Parts 1 & 2) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: Honky Tonk (Parts 1 & 2) Country: France Released: 1972 Style: Soul MP3 version RAR size: 1541 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1285 mb WMA version RAR size: 1650 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 670 Other Formats: ASF VOC AA VOC DMF AU APE Tracklist A Honky Tonk (Part 1) 3:05 B Honky Tonk (Part 2) 3:29 Companies, etc. Printed By – S.I.A.T. Distributed By – Polydor Credits Performer – James Brown - The Creator* Producer, Arranged By – James Brown Written-By – B. Doggett*, B. Butler*, C. Scott*, H. Glover*, S. Shepherd* Notes Recorded in U.S.A. D. R. Distribution exclusive Polydor SIAT - Paris Made in France Barcode and Other Identifiers Price Code: Ⓙ Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The James Brown Soul PD-14129 Honky Tonk (7") Polydor PD-14129 US 1972 Train The James Brown Soul 2066-216 Honky Tonk (7") Polydor 2066-216 UK 1972 Train The James Brown Soul Honky Tonk, Parts 1 & 2 2066 216 Polydor 2066 216 Netherlands 1972 Train (7", Single) The James Brown Soul 2066-216 Honky Tonk (7") Polydor 2066-216 UK 1972 Train The James Brown Soul 2066 216 Honky Tonk (7", Single) Polydor 2066 216 Italy 1972 Train Related Music albums to Honky Tonk (Parts 1 & 2) by The James Brown Soul Train The Rolling Stones, James Brown - Honky Tonk Woman / Mother Popcorn Bill Doggett - Honky Tonk A-La Mod! Hutch Davie - Honky Tonk Train / Woodchopper's Ball James Brown - Talking Loud And Saying Nothing James Brown - Superbad, Superslick The James Brown Soul Train - Honky Tonk (Part 1 & 2) James Brown - I'm A Greedy Man James Brown - Stoned To The Bone. -

What We Want to Hear

Night Sky Sangha Inquiry into Awakening (Facebook posts Ju l y 201 8 – December 201 8 ) Chapters Rattle me this Batman? ................................ ................................ ................................ ........................... 5 Iridescent Fracticality: The Case of the Missing Emptiness ................................ ................................ ....... 6 Delight & Erasure ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 8 May as well be lizards ................................ ................................ ................................ .............................. 9 Radioactive Presence ................................ ................................ ................................ ............................. 10 Somatic Self Reference ................................ ................................ ................................ .......................... 11 A break from delusion ................................ ................................ ................................ ........................... 13 Being & Convincing ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ 14 What should I do about myself? ................................ ................................ ................................ ............ 15 Face it, you're the most annoying person you know ................................ ............................... -

Records for Sale - Imports Rare Funk Prince Public Enemy Techno

records for sale - imports rare funk prince public enemy techno http://www.wyndelllong.com/v_list.htm Records & CDs for sale [email protected] download this list as a pdf HERE (right click 'save as') 708.263.8935 look titles up by name or catalog # on discogs.com location: flossmoor IL 60422 usa will ship anywhere in the known galaxy, and I do take paypal. rap pop r&b albums for sale 808 state - 10 x 10 12" .... prince - 1999 808 state - one in ten 12" prince - alphabet st. 12" apollonia 6 - sex shooter 12" prince - america / girl 12" art of noise - close up 12" prince - another lonely christmas / I would die for u 12" art of noise - dragnet 12" prince - around the world in a day art of noise - in no sense, nonsense prince - batdance / 200 baloons 12" art of noise - in visible silence prince - batman soundtrack art of noise - into battle prince - black album art of noise - kiss 12" prince - gett off 12" art of noise - legacy 12" prince - graffiti bridge 12" art of noise - legs 12" prince - I wish you heaven / camille - scarlett pussy 12" art of noise - paranoima 12" prince - if I was your girlfriend / shockadelic 12' art of noise - paranoimia 89' 12" prince - kiss / love or money 12" art of noise - peter gunn 12" prince - let's go crazy / erotic city 12' art of noise - who's afraid of the art of noise prince - lovesexy art of noise - yebo! 12" prince - paisley park (import) 12" beastie boys - shadrach 12" prince - parade beastie boys - shake your rump / hey ladies 12" prince - partyman / purple party mix 12" blow monkees - digging your -

Dawn of a New Apocalypse: Engagements with the Apocalyptic Imagination in 2012 and Primitvist Discourse

DAWN OF A NEW APOCALYPSE: ENGAGEMENTS WITH THE APOCALYPTIC IMAGINATION IN 2012 AND PRIMITVIST DISCOURSE Beckett Warren A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2008 Committee: Cynthia Baron, Advisor Gary Heba © 2008 Beckett Warren All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Cynthia Baron, Advisor Apocalypse is often viewed entirely as a politically conservative phenomenon, conjuring images of evangelical Christians anxiously awaiting the return of Christ. However, such a reading oversimplifies competing tensions within apocalyptic discourse. This study examines interpretations of ancient apocalypses, both Jewish and Christian, paying particular attention to the workings of what has been termed the apocalyptic imagination in order to establish a basic framework to consider contemporary instances. The apocalyptic imagination may be characterized as a “revolution of the imagination” and is largely concerned with the status of truth, and what ways of knowing may constitute truth. Additionally, apocalypse may be calibrated either towards a focus on destruction and purification or creation and redemption. The condition of postmodernity and “postmodernists” have been characterized as apocalyptic in and of themselves. This study argues that contemporary engagements with the apocalyptic imagination are largely informed by a perceived failure of the Enlightenment project, both in terms of politics and ways of knowing. Speculations about a nearing “end” of the Mayan calendar identify a coming apocalypse in the year 2012. Debates within this discourse, specifically between Daniel Pinchbeck and Whitley Strieber, illustrate the tension between purification and redemption. Furthermore, there is a concern with reexamining what constitutes knowledge, particularly that feelings about the world are worth knowing. -

Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain

Resistance Through Rituals Youth subcultures in post-war Britain Edited by Stuart Hall and Tony Jefferson First published in 1975 as Working Papers in Cultural Studies no. 7/8 Eighth impression 1991, HarperCollinsAcademic Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © The Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, University of Birmingham 1976 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work. ISBN 0-203-22494-9 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-22506-6 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-09916-1 (Print Edition) CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 THEORY 1 SUBCULTURES, CULTURES AND CLASS: A theoretical overview John Clarke, Stuart Hall, Tony Jefferson & Brian Roberts 9 SOME NOTES ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE SOCIETAL CONTROL CULTURE AND THE NEWS MEDIA: The construction of a law and order campaign CCCS Mugging Group 75 ETHNOGRAPHY CULTURAL RESPONSES OF THE TEDS: The defence of space and status Tony Jefferson 81 THE MEANING OF MOD Dick Hebdige 87 THE SKINHEADS AND THE MAGICAL RECOVERY OF COMMUNITY John Clarke 99 DOING NOTHING Paul Corrigan 103 THE CULTURAL MEANING OF DRUG USE Paul E.Willis 106 ETHNOGRAPHY THROUGH THE LOOKING-GLASS: The case