Proceedings of the Symposium on Dynamics and Management Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Climatology

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE Inc. © Eyewire, OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER 1Introduction to Climatology © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION those specializingNOT FOR in glaciology, SALE OR as wellDISTRIBUTION as special- Chapter at a Glance ized physical geographers, geologists, and ocean- Meteorology and Climatology ographers. The biosphere, which crosscuts the Scales in Climatology lithosphere, hydrosphere, cryosphere, and atmo- Subfields of Climatology sphere, includes the zone containing all life forms © Jones & BartlettClimatic Learning, Records andLLC Statistics © Joneson the& Bartlettplanet, including Learning, humans. LLC The biosphere NOT FOR SALE SummaryOR DISTRIBUTION NOT FORis examined SALE by OR specialists DISTRIBUTION in the wide array of life Key Terms sciences, along with physical geographers, geolo- Review Questions gists, and other environmental scientists. Questions for Thought The atmosphere is the component of the system © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLCstudied by climatologists ©and Jones meteorologists. & Bartlett Ho- Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONlistic interactions betweenNOT the FORatmosphere SALE and OR DISTRIBUTION Climatology may be described as the scientific each combination of the “spheres” are important study of the behavior of the atmosphere—the contributors to the climate (Table 1.1), at scales thin gaseous layer surrounding Earth’s surface— from local to planetary. Thus, climatologists must integrated over time. Although this definition is draw on knowledge generated in several natural © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC certainly acceptable, it fails to capture fully the and sometimes social scientific disciplines to un- NOTscope FOR of SALE climatology. -

Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Habitat Suitability of Fagus Sylvatica L. Forests in Spain

Plant Biosystems - An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology Official Journal of the Societa Botanica Italiana ISSN: 1126-3504 (Print) 1724-5575 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tplb20 Potential impacts of climate change on habitat suitability of Fagus sylvatica L. forests in spain Sara del Río, Ramón Álvarez-Esteban, Eusebio Cano, Carlos Pinto-Gomes & Ángel Penas To cite this article: Sara del Río, Ramón Álvarez-Esteban, Eusebio Cano, Carlos Pinto-Gomes & Ángel Penas (2018): Potential impacts of climate change on habitat suitability of Fagus sylvatica L. forests in spain, Plant Biosystems - An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology, DOI: 10.1080/11263504.2018.1435572 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2018.1435572 View supplementary material Published online: 22 Feb 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 10 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tplb20 PLANT BIOSYSTEMS - AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL DEALING WITH ALL ASPECTS OF PLANT BIOLOGY, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2018.1435572 Potential impacts of climate change on habitat suitability of Fagus sylvatica L. forests in spain Sara del Ríoa,b , Ramón Álvarez-Estebanc , Eusebio Canod , Carlos Pinto-Gomese and Ángel Penasa,b aDepartment of Biodiversity and Environmental Management (Botany), University of León, León, Spain; bFaculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Mountain Livestock Institute (CSIC-ULE), University of León, León, Spain; cFaculty of Economics and Business, Department of Economics and Statistics (Statistics and Operational Research), University of León, León, Spain; dDepartment of Animal and Plant Biology and Ecology, Botanical Section, University of Jaén, Jaén, Spain; eDepartamento de Paisagem, Ambiente e Ordenamento/Instituto de Ciências Agrárias e Ambientais Mediterrânicas (ICAAM). -

Freshwater Aquatic Biomes GREENWOOD GUIDES to BIOMES of the WORLD

Freshwater Aquatic Biomes GREENWOOD GUIDES TO BIOMES OF THE WORLD Introduction to Biomes Susan L. Woodward Tropical Forest Biomes Barbara A. Holzman Temperate Forest Biomes Bernd H. Kuennecke Grassland Biomes Susan L. Woodward Desert Biomes Joyce A. Quinn Arctic and Alpine Biomes Joyce A. Quinn Freshwater Aquatic Biomes Richard A. Roth Marine Biomes Susan L. Woodward Freshwater Aquatic BIOMES Richard A. Roth Greenwood Guides to Biomes of the World Susan L. Woodward, General Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roth, Richard A., 1950– Freshwater aquatic biomes / Richard A. Roth. p. cm.—(Greenwood guides to biomes of the world) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-33840-3 (set : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-313-34000-0 (vol. : alk. paper) 1. Freshwater ecology. I. Title. QH541.5.F7R68 2009 577.6—dc22 2008027511 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2009 by Richard A. Roth All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008027511 ISBN: 978-0-313-34000-0 (vol.) 978-0-313-33840-3 (set) First published in 2009 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Contents Preface vii How to Use This Book ix The Use of Scientific Names xi Chapter 1. -

Caribbean Marine Science

Caribbean Marine Science May 2009 Official Newsletter of the AMLC Published Spring and Fall Travel information: Melville Hall International. Contents Airport is located on the East coast of Dominica near the town of Marigot. It takes about an hour to cross the island along the trans-insular "Imperial Road" into Association News ........……….....…….…… 1 Roseau. This trip takes you through forest reserves Profile …………………………………….. 2 and you will be passing by the Morne Trois Pitons General Interest ……….…………………... 4 National Park (UNESCO World Heritage Site). The Meetings/Workshops …………………….. 8 roads are narrow, steep and winding. Participants are Course Offerings ..……….………………… 8 responsible for their transfer from the airport to the New Books/publications ……..………….. 11 hotel and back. The regulated transfer fares are Change of Address Form ……..…………. 12 Eastern Caribbean Dollars 65.00 (US$ 25.00) for Dues/Membership Form .…………………. 13 “Taxis" (minibuses), and as long as there is more than AMLC Background & Goals …………..… 13 one passenger in the bus, each passenger is to pay no AMLC Officers …………………....……… 14 more than the $25.00 set fee. Please inform the drivers to which hotel you need to go. Have a good trip! Meeting participants are invited to look for representatives of Choice Taxi (Mr. Ben Senhouse) Association News for their transfers. Choice Taxi has been informed of the event." From the Editors’ desk Please be advised that the Transportation Security Our greetings to all AMLC members. We are ready Administration (TSA) has instituted new rules and for our upcoming Scientific meeting next week in procedures that require airlines to present the TSA Dominica. The program looks fine and highly with certain specific identity information for all informative with over 50 oral presentations and 40 passengers. -

Positive Feedback Between Future Climate Change and the Carbon Cycle

GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, VOL. 28, NO. 8, PAGES 1543-1546, APRIL 15 , 2001 Positive feedback between future climate change and the carbon cycle Pierre Friedlingstein, Laurent Bopp, Philippe Ciais, IPSL/LSCE, CE-Saclay, 91191, Gif sur Yvette, France Jean-Louis Dufresne, Laurent Fairhead, Herv´eLeTreut, IPSL/LMD, Universit´e Paris 6, 75252, Paris, France Patrick Monfray, and James Orr IPSL/LSCE, CE-Saclay, 91191, Gif sur Yvette, France Abstract. Future climate change due to increased atmo- two carbon simulations. In the “constant climate” simula- sphericCO 2 may affect land and ocean efficiency to absorb tion the carbon models are forced by a CO2 increase of 1% atmosphericCO 2. Here, using climate and carbon three- per year and the control climate from the OAGCM. In the dimensional models forced by a 1% per year increase in at- “climate change” simulation, the carbon models are forced mosphericCO 2, we show that there is a positive feedback by the same 1%/yr CO2 increase as well as the climate from between the climate system and the carbon cycle. Climate the transient climate run. change reduces land and ocean uptake of CO2,respectively In this experiment, atmosphericCO 2 and monthly aver- by 54% and 35% at 4 × CO2 . This negative impact im- aged climate fields from the IPSL OAGCM [Braconnot et al., plies that for prescribed anthropogenic CO2 emissions, the 2000] are used to drive both terrestrial and oceanic carbon atmosphericCO 2 would be higher than the level reached if cycle models. These two models allow one to translate an- climate change does not affect the carbon cycle. -

Meteorology and Climatology

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION PART 1 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONThe BasicsNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC CHAPTER© 1 Jones Introduction & Bartlett to Climatology Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT MeteorologyFOR SALE and Climatology OR DISTRIBUTION Scales in Climatology Subfields of Climatology Climatic Records and Statistics Summary © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLCKey Terms © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONReview Questions NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Questions for Thought CHAPTER 2 Atmospheric Structure and Composition © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC Origin of the Earth© Jonesand Atmosphere & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Atmospheric CompositionNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Faint Young Sun Paradox Atmospheric Structure Summary Key Terms © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC Review Questions NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT QuestionsFOR SALEfor Thought OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, -

A Glossary for Biometeorology

Int J Biometeorol DOI 10.1007/s00484-013-0729-9 ICB 2011 - STUDENTS / NEW PROFESSIONALS A glossary for biometeorology Simon N. Gosling & Erin K. Bryce & P. Grady Dixon & Katharina M. A. Gabriel & Elaine Y.Gosling & Jonathan M. Hanes & David M. Hondula & Liang Liang & Priscilla Ayleen Bustos Mac Lean & Stefan Muthers & Sheila Tavares Nascimento & Martina Petralli & Jennifer K. Vanos & Eva R. Wanka Received: 30 October 2012 /Revised: 22 August 2013 /Accepted: 26 August 2013 # The Author(s) 2013. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Here we present, for the first time, a glossary of berevisitedincomingyears,updatingtermsandaddingnew biometeorological terms. The glossary aims to address the need terms, as appropriate. The glossary is intended to provide a for a reliable source of biometeorological definitions, thereby useful resource to the biometeorology community, and to this facilitating communication and mutual understanding in this end, readers are encouraged to contact the lead author to suggest rapidly expanding field. A total of 171 terms are defined, with additional terms for inclusion in later versions of the glossary as reference to 234 citations. It is anticipated that the glossary will a result of new and emerging developments in the field. S. N. Gosling (*) L. Liang School of Geography, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG7 Department of Geography, University of Kentucky, Lexington, 2RD, UK KY, USA e-mail: [email protected] E. K. Bryce P. A. Bustos Mac Lean Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, Department of Animal Science, Universidade Estadual de Maringá Toronto, ON, Canada (UEM), Maringa, Paraná, Brazil P. G. Dixon S. -

Abstract Pdf 31 Kb

Biomass and soil carbon: Major research needs for the coming decade Roger M. Gifford1, R. John Raison2 and Miko U.F. Kirschbaum3 1CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO Box 1600 Canberra, ACT 2601 2ENSIS, PO Box E4008, Kingston, ACT 2604 3Landcare Research, Private Bag 11052, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand Abstract We have selected nine topics of particular importance for gaining a better understanding of the inter-relationship between vegetation, the global terrestrial carbon cycle and climate change. Four of these priorities have an Australia-specific focus. In priority order they are: 1) Reduce uncertainty in Australian continental net primary productivity. A primary input to any terrestrial carbon cycle model is an estimate of the rate of annual uptake of CO2 from the atmosphere. Ability to model the baseline is a prerequisite to convincing modelling of its response to climatic change. Review of 18 model estimates of the long-term average net primary productivity of the Australian continent (Roxburgh et al. 2005) reported an 8-fold range from 0.4 Gt C yr-1 to 3.3 Gt C yr-1. Whilst some of this variation is due to identified modelling differences (e.g. use of current actual land cover vs potential vegetation cover, or driven by the weather in specific years vs long- term climatic averages), the extent of this range of estimates does highlight that knowledge of national NPP is still inadequate for many applications. A national stratified network of long-term field sites is needed to estimate NPP by an agreed methodology, linked with model development and satellite imagery for interpolation, and augmented with a small number of sites for intensive measurements and determination of component C fluxes including towers for eddy-covariance measurements. -

Climate in Architecture: Revision of Early Origins Ursula Anna Freire Castro Univerity of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Latin American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 4-8-2019 Climate in architecture: revision of early origins Ursula Anna Freire Castro Univerity of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ltam_etds Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Climate Commons, and the Other Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Freire Castro, Ursula Anna. "Climate in architecture: revision of early origins." (2019). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ltam_etds/ 49 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Latin American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i URSULA ANNA FREIRE CASTRO Candidate LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: ELENI BASTÉA, Chairperson MARIA LANE CHRIS DUVALL DAVID SCHNEIDER ii CLIMATE IN ARCHITECTURE: REVISION OF EARLY ORIGINS by URSULA ANNA FREIRE CASTRO Architect, Universidad Central del Ecuador, 2008 Master Architectural Design, Universidad Central del Ecuador, 2012 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Latin American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2019 iii DEDICATION With all my love, to Kati, Max, and Mina. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I heartily and warmly acknowledge the support of my Committee of Studies, Eleni Bastéa, Maria Lane, David Schneider and Chris Duvall, who always were generous with their knowledge and time. -

Cherax Longipes (A Crayfish, No Common Name) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Cherax longipes (a crayfish, no common name) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, September 2011 Revised, December 2017 Web Version, 5/20/2018 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Holthuis (1982): “All 8 species of the subgenus Cherax inhabit the Central Mountain Range in the Wissel Lakes region of Irian [Irian Jaya, a.k.a. West Papua province, Indonesia] […] 2 of the species (C. longipes and C. solus) are known only from Tigi Lake […]” Status in the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the United States. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has listed the crayfish Cherax longipes as a prohibited species. Prohibited nonnative species “are considered to be dangerous to the ecology and/or the health and welfare of the people of Florida. These species are not allowed to be personally possessed or used for commercial activities” (FFWCC 2017). From Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife (2017): “(1) Prohibited aquatic animal species. RCW 77.12.020 1 These species are considered by the commission to have a high risk of becoming an invasive species and may not be possessed, imported, purchased, sold, propagated, transported, or released into state waters except as provided in RCW 77.15.253. […] The following species are classified as prohibited animal species: […] Family Parastacidae: Crayfish: All genera except Engaeus, and except the species Cherax quadricarninatus [sic], Cherax papuanus, and Cherax tenuimanus.” Means of Introduction into the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the United States. -

List of Journal Abbreviations

List of Journal Abbreviations This list is based mostly on ISO 4:1997, the standard titled "Information and documentation - rules for the abbreviation of title words and titles of publications," and the List of Title Word Abbreviations maintained by the International Standard Serial Number International Center A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W Y Z A • Abh. Akad. Wiss. Lit. Mainz Math.-Nat.wiss. Kl.| Abhandlungen. Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Klasse • Abh. Nat.wiss. Ver. Brem. | Abhandlungen. Naturwissenschaftliche Verein zu Bremen • ACIAR Proc. | ACIAR Proceedings • ACOPS Yearb. | ACOPS Yearbook • Acoust. Phys. | Acoustical Physics • Acta Acad. Agric. Tech. Olst., Geod. Ruris Regul. | Acta Academiae Agriculturae ac Technicae Olstenensis. Geodaesia et Ruris Regulatio • Acta Acad. Agric. Tech. Olst., Protect. Aquar. Piscat. | Acta Academiae Agriculturae ac Technicae Olstenensis. Protectio Aquarum et Piscatoria • Acta Acad. Agric. Tech. Olst., Technol. Aliment. | Acta Academiae Agriculturae ac Technicae Olstenensis. Technologia alimentarum • Acta Acad. Agric. Tech. Olst., Vet. | Acta Academiae Agriculturae ac Technicae Olstenensis. Veterinaria. • Acta Adriat. | Acta Adriatica • Acta Amazon. | Acta Amazonica • Acta Anat. | Acta Anatomica • Acta Arct. | Acta Arctica • Acta Biol. Cracov., Bot. | Acta Biologica Cracoviensia. Serie Botanique • Acta Biol. Cracov., Zool. | Acta Biologica Cracoviensia. Serie Zoologique • Acta Biol. Hung. | Acta Biologica Hungarica • Acta Biol. Jugosl.,. B | Acta Biologica Jugoslavica. Serija B. Mikrobiologija • Acta Biol. Jugosl., E | Acta Biologica Jugoslavica. Serija E. Ichthyologia • Acta Biol. Med. Soc. Sci. Gedanensis | Acta Biologica et Medica Societas Scientiarum Gedanensis • Acta Biol. Paran. | Acta Biologica Paranaense • Acta Biol. Venez. -

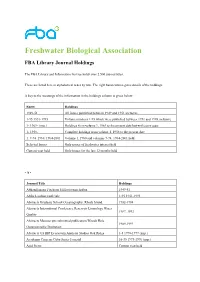

Here in Alphabetical Order by Title

Freshwater Biological Association FBA Library Journal Holdings The FBA Library and Information Service holds over 2,500 journal titles. These are listed here in alphabetical order by title. The right hand column gives details of the holdings. A key to the meanings of the information in the holdings column is given below: Entry Holdings 1949-51 All issues published between 1949 and 1951 inclusive 1-95 1951-1995 Volume numbers 1-95 which were published between 1951 and 1995 inclusive 1- 1969- (imp.) Holdings from volume 1, 1969 to the present date but with some gaps 1- 1958- Complete holdings from volume 1, 1958 to the present date 1, 7-74 1960, 1964-2001 Volume 1, 1960 and volumes 7-74, 1964-2001 held Selected Issues Only issues of freshwater interest held Current year held Only issues for the last 12 months held - A - Journal Title Holdings Abhandlungen Fischerei Hilfswissenschaften 1949-51 Abiks Loodusevaatlejale 1-95 1951-1995 Abstracts Graduate School Oceanography. Rhode Island 1982-1984 Abstracts International Conference Reservoir Limnology Water 1987, 1992 Quality Abstracts Manuscripts submitted publication Woods Hole 1989-1993 Oceanographic Institution Abstracts US IBP Ecosystem Analysis Studies Oak Ridge 1-5 1970-1977 (imp.) Academia Ciencias Cuba Series Forestal 16-35 1973-1976 (imp.) Acid News Current year held Acta Academie Agriculturae Technicae Olstensis Protectio 14-21 1985-1997 Aquarum Piscatoria Acta Academie Agriculturae Technicae Olstensis Zootechnica 30-34 1986-1992 Acta Adriatica 2(4)- 1941- (imp.) Acta Biologica Academiae