FIELD WORKS : Explorations in the Tall Grass Prairie Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enjoy the Journey of Cultural Learning

International Student Program Homestay Guide Enjoy the journey of cultural learning isp.lrsd.net CONTENTS Welcome ....................................................................3 Health Insurance Guide ...........................................................10 International Student Program Manitoba Health ........................................................................11 Homestay Guidelines ................................................................ 3 What to Do and How to Claim ...............................................11 Information Changes ................................................................ 3 Helpful Website Links and Contact Numbers .................... 4 Living in Canada ........................................................................12 Contact Information, Location and Map .............................. 5 Events and Permission Forms ...............................................16 Activities and Things to do in Winnipeg ............................... 6 Who Signs What? .....................................................................17 Fun Family Activities ..................................................................7 Homestay Program ................................................. 18 Arriving in Canada .....................................................8 What is Expected from the Homestay Family..................20 Airport Arrival ............................................................................. 8 Homestay Food Do’s and Don’ts ..........................................23 -

Parks and Recreation Photograph Collection

CITY OF WINNIPEG ARCHIVES PARKS AND RECREATION PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION FINDING AID Parks ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Community Infrastructure and Programming ................................................................................62 City Staff, Events, and Promotions ................................................................................................. 116 Maintenance Services and Infrastructure ..................................................................................... 143 A City at Leisure ................................................................................................................................. 154 Winnipeg Landmarks and Businesses ........................................................................................... 159 Weather Related Events ................................................................................................................... 178 Signs and Stencils .............................................................................................................................. 181 National and Provincial Landmarks ............................................................................................... 182 Oversized Items ................................................................................................................................. 186 DISCLAIMER: this finding aid was produced manually and may contain -

Summer Family Fun During COVID-19

Summer Family Fun During COVID-19: What’s Open Many more facilities are expected to open soon with additional COVID-19 Protocols, stay tuned for a Phase 3 updated list! Museums, Zoos & More Assiniboine Park Zoo Open Daily from 9:00 am – 5:00 pm *Children 2 & under free with general admission https://www.assiniboineparkzoo.ca/zoo/home/plan-your-visit/hours-rates Manitoba Museum Open Saturdays & Sundays in June from 11:00 am – 5:00 pm https://manitobamuseum.ca/main/visit/hours-admissions/ Canadian Museum for Human Rights *Opening Wednesday, June 17th Open Tuesday to Saturday from 10:00am – 5:00 pm https://humanrights.ca/COVID-19 Winnipeg Railway Museum Open Daily from 10:00 am – 4:00 pm http://www.wpgrailwaymuseum.com Winnipeg Art Gallery Open Tuesday to Sunday 11:00 am – 5:00 pm, with extended Friday hours until 9:00 pm https://wag.ca/visit/hours-admission/ Living Prairie Museum Open Sundays 10:00 am – 5:00 pm https://www.winnipeg.ca/publicworks/parksOpenSpace/livingprairie/ Fort Whyte Alive Open Weekdays 9:00 am – 5:00 pm & Weekends 10:00 am – 5:00 pm https://www.fortwhyte.org The Golf Dome Mini Golf Open 10:00 am – 8:00 pm http://www.thegolfdome.ca/hours.php https://www.parentingduringthepandemic.com Water Fun The following Winnipeg spray pads are open from 9:30am-8:30pm daily: *Note that no washroom facilities are available at any of the following https://www.winnipeg.ca/cms/recreation/facilities/pools/spraypads.stm • Central Park • Fort Rouge • Freight House • Gateway • Jill Officer Park • Lindenwoods • Lindsey Wilson Park • Machray Park • Provencher Park • Park City West • River Heights • St. -

2015 Report on Park Assets

Appendix A 2015 Report on Park Assets Asset Management Branch Parks and Open Space Division Public Works Department Table of Contents Summary of Parks, Assets and Asset Condition by Ward Charleswood-Tuxedo-Whyte Ridge Ward ................................................................................................... 1 Daniel McIntyre Ward .................................................................................................................................. 9 Elmwood – East Kildonan Ward ................................................................................................................. 16 Fort Rouge – East Fort Garry Ward ............................................................................................................ 24 Mynarski Ward ........................................................................................................................................... 32 North Kildonan Ward ................................................................................................................................. 40 Old Kildonan Ward ..................................................................................................................................... 48 Point Douglas Ward.................................................................................................................................... 56 River Heights – Fort Garry Ward ................................................................................................................ 64 South Winnipeg – St. Norbert -

Keeyask Generation Project: Public Involvement Supporting Volume

Keeyask Generation Project Environmental Impact Statement Supporting Volume Public Involvement June 2012 KEEYASK GENERATION PROJECT June 2012 Round 1 PIP - Proposed Keeyask Generation Project: Meeting with Ilford Mayor and Council Final Meeting Notes Date of Meeting: October 30, 2008 – 11:00 am to 12:00 pm Th Location: Ilford, MB Town Office In Attendance: James Chornoby Mayor Jennifer Bloomfield Councillor Harold Blan Councillor Dwayne Flett Councillor Fiona Scurrah Manitoba Hydro Gordon Wastesicoot KCN Victor Flett KCN Jonathan Kitchekeesik Jr. KCN Wayne Marcinyshyn KCN John Osler InterGroup Consultants David Lane InterGroup Consultants PURPOSE OF MEETING The meeting was requested by the Environmental Assessment Team for the proposed Keeyask Generation Project to: Provide background information about the proposed Keeyask Generation Project; Begin dialogue about the Environmental Assessment process; Provide initial information about the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and its associated Public Involvement Program (PIP); and Identify issues and concerns Mayor and Council has with the proposed project, the EIA and the PIP. The meeting is one of a series of sessions being held with communities in the Churchill-Burntwood- Nelson area and with potentially affected and interested organizations as part of Round 1 of the PIP. Two additional rounds of meetings are contemplated as information from the EIA becomes available. MEETING PROCESS Following introductions and a prayer, John Osler presented information on the project, the EA process and the purpose of Round 1 PIP. This included details on the size and location of the project, project components and construction activities, potential partnership with the in-vicinity communities, the EA PIP, environmental approvals, and project environmental studies. -

Municipal Manual 2004 Manitoba Cataloguing in Publication Data

Municipal Manual 2004 Manitoba Cataloguing in Publication Data Winnipeg (Man.). Municipal Manual - 1904 - Also available in French Prepared by the City Clerk’s Dept. Issn 0713 = Municipal Manual - City of Winnipeg. 1. Administrative agencies - Manitoba - Winnipeg - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Executive departments - Manitoba - Winnipeg - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 3. Winnipeg (Man.). City Council - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 4. Winnipeg (Man.) - Guidebooks. 5. Winnipeg (Man.) - Politics and government - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 6. Winnipeg (Man.) - Politics and government - Directories. I. Winnipeg (Man.). City Clerk’s Department. JS1797.A13 352.07127’43 Cover Photograph: The Provencher Twin Bridge and the Pedestrian walkway known as “Esplanade Riel”. The dramatic cable-stayed pedestrian bridge is Winnipeg’s newest landmark, and was officially opened on December 31, 2003. The Cover Photo was taken by Winnipeg Sun photographer, John Woods and is used with permission from the Toronto Sun Publishing Company. All photographs contained within this manual are the property of the City of Winnipeg Archives, the City of Winnipeg and the City Clerk’s Department. Permission to reproduce must be requested in writing to the City Clerk’s Department, Council Building, City Hall, 510 Main Street, Winnipeg, MB, R3B 1B9. The City Clerk’s Department gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Creative Services Branch in producing this document. Table of Contents Introduction 3 Preface 4A Message from the Mayor 5A Message from the Chief Administrative Officer -

Your Guide to Winnipeg Public Library

Your Guide At The to Winnipeg LIBRARY Public Library July-August 2018 winnipeg.ca/library FREE content library news 3-5 for adults 6-12 for teens & tweens 13-15 for children & families 16-21 membership guide 22-23 locations & hours 24 ON THE COVER: Emily and Maggie From the Manager are kicking off summer with the TD Summer Reading Club. Visit your local Summer arrives with the promise of long, golden days and more time to spend on branch to sign up today! outdoor pursuits. At Winnipeg Public Library, July and August are all about the TD Summer Reading Club! Children up to age 12 are invited to drop by any branch of the library to register and to pick up their free reading kit that includes activities and a calendar to track time spent reading. Making time for reading over the summer encourages children to become stronger readers and helps them maintain their reading skills over the holiday break. And reading is not just an indoor activity! Join the Walk about in Bruce Park at the St. James-Assiniboia branch or Rambling Recommendations at the Charleswood branch for a chance to take your love of reading outdoors. Details on the TD Summer Reading Club, the programs mentioned above and much more are available in this newsletter and at winnipeg.ca/library. Enjoy the summer while it’s here! • Ed Cuddy, Manager of Library Services EDITOR Patricia Bal DESIGN Sherry Galagan Volume 19, Number 4 At The Library is your bimonthly guide to the news and programs of Winnipeg Public Library. -

Landscape Aarchitectsrchitects and Landscape Architecture in Manitoba Cover Art: Don Reichert, Icefog, 2005

Catherine Macdonald MAKING A PLACE: A History of Landscape AArchitectsrchitects and Landscape Architecture in Manitoba Cover Art: Don Reichert, Icefog, 2005 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Macdonald, Catherine, 1949- Making a place [electronic resource] : a history of landscape architects and landscape architecture in Manitoba / Catherine Macdonald. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-9735539-0-1 1. Landscape architecture--Manitoba--History. 2. Landscape architects--Manitoba--History. 3. Landscape design--Manitoba--History. I. Manitoba Association of Landscape Architects II. Title. SB469.386.C3M33 2005 712’.097127’09 C2005-904024-6 The Manitoba Association of Landscape Architects acknowledges with gratitude the financial assistance of the following agencies in the publication of this volume: the Landscape Architecture Canada Foundation; the Department of Canadian Heritage (Winnipeg Development Agreement); The Visual Arts Section of the Canada Council for the Arts; the Province of Manitoba Heritage Grants Program; and the City of Winnipeg. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1826 Foreword by Professor Gerald Friesen 05 Author’s Preface and Acknowledgements 06 Author’s Biography 09 Abbreviations 09 1893 Chapter 1. Design by Necessity: The Landscape is Shaped 1826-1893 10 1894 Chapter 2. The City on the Horizon 1894-1940 30 Chapter 3. Prairie Modernism 1940-1962 58 Chapter 4 Establishing the Profession 1962-1972 89 Chapter 5 Riding the Economic Tiger 1973-1988 136 1940 1940 Chapter 6 Looking For the Way Forward 1989-1998 188 1962 Selected Bibliography 225 1962 1972 1973 1988 1989 1998 FOREWORD When Catherine Macdonald first asked me to read this history of landscape architecture in the province, and to give her patrons, the Manitoba Association of Landscape Architects, some estimate of its potential audience, I assumed that the book would be a brief, bare-bones history of an organization. -

ORGANIZATIONS FUNDED in 2018 (Winnipeg

ORGANIZATIONS FUNDED IN 2018 (Winnipeg - sorted by area) ORGANISATIONS FINANCÉES EN 2018 (Winnipeg - classées par secteur) Charleswood-Tuxedo Archers & Bowhunters Assoc of MB Assiniboine Park Conservancy Canadian Mennonite University Family Dynamics of Winnipeg Fort Whyte Alive Friends of the Harte Trail Grace Community Church Manitoba Cycling Association Manitoba Sailing Assoc. Nature Manitoba Oasis Community Church Purple Loosestrife Project of Manitoba Rotary Club of Winnipeg - Charleswood Varsity View Community Centre Winnipeg Military Family Resource Centre Winnipeg South Minor Baseball Association Daniel McIntyre Daniel McIntyre / St. Matthew's Comm. Assoc. Emmanuel Mission Church Ethio-Canadian Cultural Academy Girls with Pride and Dignity Foundation Living Bible Explorers (Winnipeg) Mission Baptist Church Monyjang Society of Manitoba Mood Disorders Association of Manitoba Robert A. Steen Memorial Community Centre Sargent Park Lawn Bowling Club Spence Neighbourhood Assoc. Valour Community Centre West Central Community Program West Central Women's Resource Centre West End BIZ Wii Chii Waakanak Learning Centre Winnipeg Art Gallery Winnipeg School Division (special needs project) Elmwood-East Kildonan Bronx Park Community Centre Chalmers Community Centre Chalmers Neighbourhood Renewal Corp. Congo Canada Charity Foundation East Elmwood Community Centre Elmwood Community Resource Centre Elmwood Giants Baseball Club Elmwood Mennonite Brethren Church Frontier College Hope Centre Ministries One Hope Min. of Canada-Adventure Day Camp River -

O. V. Jewitt Community School REPORT to COMMUNITY 2011-2012

O. V. Jewitt Community School REPORT TO COMMUNITY 2011-2012 Natural Playscape & Healthy Living Outdoor Classroom Field Trips Spirit Week: “Earth Week” focus Development of a natural playscape where Intramurals young children can engage in creative play. Interscholastic Sports Components include: log cabins, water Aviation Museum Regular Phys. Ed. classes feature, canoe, forest; further development Manitoba Museum and Planetarium Middle Years daily Active Living Breaks taking place over the summer Fort Whyte Family Life Kidsfest Classroom gardens Terry Fox Run Curricular connections through the outdoors Oak Hammock Marsh Outdoor Education Writing Children’s Museum Winter Activity Days Art Living Prairie Museum Classroom focus on fitness/movement Science Assiniboine Park Zoo breaks Math Steinbach Museum Middle Years Life Days Reading Mariash Quarry MADD Presentation for Middle Years Community gathering/meeting place, including Grade 4 and 4/5 dance class a chess/checker table and pergola Classroom discussions on nutrition Alternative classroom space Jump Rope for Heart Shared use with O.K. Before & After Day Care and O.V. Jewitt Family Centre Marathon Club Middle Years Winnipeg Community Police Presentation: Drug Awareness Learning Through the Arts Roots of Empathy Middle Years outings to Manitoba Theatre Student-Led Art Club: Multi-Cultural for Young People (MTYP) Awareness: Oragami and Crafts Classroom based program Middle Years Band Program Classroom book publishing and Regular monthly visits from a baby and parent Middle Years Choirs illustration Development of empathy Early Years Choirs Middle Years Exploratory classes and identifying feelings Guitar Club Special Events such as the K-3 Two families participated Grade 4/5 and 5 Dance Classes performance of “Flakes,” Grade 4 and 5 this year! Grade 5 WSO: Adventures in Music production of “I Need a Vacation” K-5 Music Program Choir and Band concerts Grade 4/5 and 5 Arts Camp Carolling in December Classroom Art Experiences Family Evening: Easter Egg Decorating African Drumming Working with Clay 3-D Art O.V. -

Habitat Means Home

(!")4!4-%!.3(/-%-!--!,3 (!")4!4-%!.3(/-%-!--!,3 FRONT FRONT -!--!,3 REAR REAR 2%$!.$'2%9315)22%,3 4HEREAREMANYKINDSOFSQUIRRELSINTHEFOREST2EDANDGREYSQUIRRELSARETHE ONESYOUWILLLIKELYSEE&LYINGSQUIRRELSONLYCOMEOUTATNIGHT2EDSQUIR 2!##//. RELSARESMALLERTHANGREYSQUIRRELSANDAREREDWITHAWHITEBELLY4HEYOFTEN 9OUCANALWAYSRECOGNIZEARACCOONBYTHEBLACKMASKITWEARSANDTHE CHATTERATYOUFORBEINGINTHEIRTERRITORY'REYSQUIRRELSAREBIGGERANDGREY BLACKRINGSONITSTAIL)TLOOKSLIKEAREALLYBIGGREYHOUSECAT2ACCOONSARE COLOUREDWITHAWHITEBELLYANDBUSHYTAIL"OTHAREHERBIVORES,OOKFORARED OMNIVORESnTHEYEATPLANTSLIKEBERRIESANDANIMALSLIKECRAYFISH TURTLES SQUIRRELNESTOFSTICKSANDLEAVESINTHETREES!NOTHERSIGNOFASQUIRRELISA MICEANDFROGS4HEYARENOCTURNALnTHATMEANSTHEYCOMEOUTATNIGHT4HEY PILEOFSEEDORNUTSHELLS SLEEPINTREESDURINGTHEDAY2IVERBOTTOMFORESTISTHEIRFAVOURITEPLACETO LIVE 2IVERS7EST!NIMALSOFTHE2IVERBOTTOM&OREST 0AGE -!--!,3 -!--!,3 FRONT -!--!,3 REAR 7()4%4!),%$$%%2 7HITE TAILEDDEERARELARGEHERBIVORES9OUCANSEETHEMEATINGGRASSATTHE EDGEOFTHEFOREST4HEYARERED BROWNINSUMMERANDGREY BROWNINWINTER 3+5.+ -ALEDEERGROWANTLERSOVERTHESUMMERTHATFALLOFFINTHEWINTER"ABYDEER %VERYONEKNOWSTHESKUNKnBLACKFURWITHAWHITESTRIPEDOWNITSBACKAND ARETHESIZEOFYOU4HEIRMOMHIDESTHEMINTHEGRASSDURINGTHEDAYnIFYOU BIGBUSHYTAIL)FYOUSEEASKUNKYOUBETTERGETOUTOFITSWAYnITSPRAYSA FINDONEJUSTLEAVEITALONE BECAUSEMOMISCLOSEBYBUTHIDING4HEBEST FOULPERFUMEIFSCARED3KUNKSAREOMNIVORES4HEYLIKEBIRDSEGGS INSECTS TIMETOSEEDEERISEARLYMORNINGANDSUNDOWN,OOKFORTHEIRTRACKSINMUD MICE PLANTSANDEVENCARRIONnDEADANIMALS ORSNOWALONGTRAILS 2IVERS7EST!NIMALSOFTHE2IVERBOTTOM&OREST -

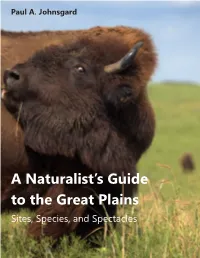

A Naturalist's Guide to the Great Plains

Paul A. Johnsgard A Naturalist’s Guide to the Great Plains Sites, Species, and Spectacles This book documents nearly 500 US and Canadian locations where wildlife refuges, na- ture preserves, and similar properties protect natural sites that lie within the North Amer- ican Great Plains, from Canada’s Prairie Provinces to the Texas-Mexico border. Information on site location, size, biological diversity, and the presence of especially rare or interest- ing flora and fauna are mentioned, as well as driving directions, mailing addresses, and phone numbers or internet addresses, as available. US federal sites include 11 national grasslands, 13 national parks, 16 national monuments, and more than 70 national wild- life refuges. State properties include nearly 100 state parks and wildlife management ar- eas. Also included are about 60 national and provincial parks, national wildlife areas, and migratory bird sanctuaries in Canada’s Prairie Provinces. Numerous public-access prop- erties owned by counties, towns, and private organizations, such as the Nature Conser- vancy, National Audubon Society, and other conservation and preservation groups, are also described. Introductory essays describe the geological and recent histories of each of the five mul- tistate and multiprovince regions recognized, along with some of the author’s personal memories of them. The 92,000-word text is supplemented with 7 maps and 31 drawings by the author and more than 700 references. Cover photo by Paul Johnsgard. Back cover drawing courtesy of David Routon. Zea Books ISBN: 978-1-60962-126-1 Lincoln, Nebraska doi: 10.13014/K2CF9N8T A Naturalist’s Guide to the Great Plains Sites, Species, and Spectacles Paul A.