The Southeastern Coastal Plain: an Overview (Fig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great's Tombolos at Tyre and Alexandria, Eastern Mediterranean ⁎ N

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Geomorphology 100 (2008) 377–400 www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Alexander the Great's tombolos at Tyre and Alexandria, eastern Mediterranean ⁎ N. Marriner a, , J.P. Goiran b, C. Morhange a a CNRS CEREGE UMR 6635, Université Aix-Marseille, Europôle de l'Arbois, BP 80, 13545 Aix-en-Provence cedex 04, France b CNRS MOM Archéorient UMR 5133, 5/7 rue Raulin, 69365 Lyon cedex 07, France Received 25 July 2007; received in revised form 10 January 2008; accepted 11 January 2008 Available online 2 February 2008 Abstract Tyre and Alexandria's coastlines are today characterised by wave-dominated tombolos, peculiar sand isthmuses that link former islands to the adjacent continent. Paradoxically, despite a long history of inquiry into spit and barrier formation, understanding of the dynamics and sedimentary history of tombolos over the Holocene timescale is poor. At Tyre and Alexandria we demonstrate that these rare coastal features are the heritage of a long history of natural morphodynamic forcing and human impacts. In 332 BC, following a protracted seven-month siege of the city, Alexander the Great's engineers cleverly exploited a shallow sublittoral sand bank to seize the island fortress; Tyre's causeway served as a prototype for Alexandria's Heptastadium built a few months later. We report stratigraphic and geomorphological data from the two sand spits, proposing a chronostratigraphic model of tombolo evolution. © 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Tombolo; Spit; Tyre; Alexandria; Mediterranean; Holocene 1. Introduction Courtaud, 2000; Browder and McNinch, 2006); (2) establishing a typology of shoreline salients and tombolos (Zenkovich, 1967; The term tombolo is used to define a spit of sand or shingle Sanderson and Eliot, 1996); and (3) modelling the geometrical linking an island to the adjacent coast. -

The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We Are Failing to Save Its Wetlands

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 8-8-2007 The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We are Failing to Save its Wetlands Lon Boudreaux Jr. University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Boudreaux, Lon Jr., "The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We are Failing to Save its Wetlands" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 564. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/564 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We Are Failing to Save Its Wetlands A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Urban Studies By Lon J. Boudreaux Jr. B.S. Our Lady of Holy Cross College, 1992 M.S. University of New Orleans, 2007 August, 2007 Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................. -

Subsurface Geology of Cenozoic Deposits, Gulf Coastal Plain, South-Central United States

REGIONAL STRATIGRAPHY AND _^ SUBSURFACE GEOLOGY OF CENOZOIC DEPOSITS, GULF COASTAL PLAIN, SOUTH-CENTRAL UNITED STATES V U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1416-G AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the current-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Survey publications re leased prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that may be listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" may no longer be available. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices listed below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books and Maps Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Tech Books and maps of the U.S. Geological Survey are available niques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications over the counter at the following U.S. Geological Survey offices, all of general interest (such as leaflets, pamphlets, booklets), single of which are authorized agents of the Superintendent of Docu copies of Earthquakes & Volcanoes, Preliminary Determination of ments. Epicenters, and some miscellaneous reports, including some of the foregoing series that have gone out of print at the Superintendent of Documents, are obtainable by mail from ANCHORAGE, Alaska-Rm. -

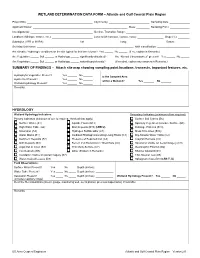

Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain Region SUMMARY of FINDINGS

WETLAND DETERMINATION DATA FORM – Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain Region Project/Site: City/County: Sampling Date: Applicant/Owner: State: Sampling Point: Investigator(s): Section, Township, Range: Landform (hillslope, terrace, etc.): Local relief (concave, convex, none): Slope (%): Subregion (LRR or MLRA): Lat: Long: Datum: Soil Map Unit Name: NWI classification: Are climatic / hydrologic conditions on the site typical for this time of year? Yes No (If no, explain in Remarks.) Are Vegetation , Soil , or Hydrology significantly disturbed? Are “Normal Circumstances” present? Yes No Are Vegetation , Soil , or Hydrology naturally problematic? (If needed, explain any answers in Remarks.) SUMMARY OF FINDINGS – Attach site map showing sampling point locations, transects, important features, etc. Hydrophytic Vegetation Present? Yes No Is the Sampled Area Hydric Soil Present? Yes No within a Wetland? Yes No Wetland Hydrology Present? Yes No Remarks: HYDROLOGY Wetland Hydrology Indicators: Secondary Indicators (minimum of two required) Primary Indicators (minimum of one is required; check all that apply) Surface Soil Cracks (B6) Surface Water (A1) Aquatic Fauna (B13) Sparsely Vegetated Concave Surface (B8) High Water Table (A2) Marl Deposits (B15) (LRR U) Drainage Patterns (B10) Saturation (A3) Hydrogen Sulfide Odor (C1) Moss Trim Lines (B16) Water Marks (B1) Oxidized Rhizospheres along Living Roots (C3) Dry-Season Water Table (C2) Sediment Deposits (B2) Presence of Reduced Iron (C4) Crayfish Burrows (C8) Drift Deposits (B3) Recent Iron Reduction -

Coastal Plain of Georgia

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIBECTOK WATER-SUPPLY PAPER UNDERGROUND WATERS OF THE COASTAL PLAIN OF GEORGIA BY L. W. STEPHENSON AND J. 0. VEATCH AND A DISCUSSION OP THE QUALITY OF THE WATERS BY R. B. DOLE Prepared in cooperation with the Geological Survey of Georgia WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1915 CONTENTS. __ Page. Introduction.............................................................. 25 Physiography.............................................................. 26 Cumberland Plateau.................................................... 26 Appalachian Valley.................................................... 27 Appalachian Mountains................................................ 27 Piedmont Plateau..................................................... 27 Coastal Plain........................................................... 28 General features................................................... 28 Physiographic subdivisions......................................... 29 Fall-line Mils................................................. 29 Dougherty plain............................................... 31 Altamaha upland............................................... 32 Southern limesink region...................................... 34 Okefenokee plain.............................................. 35 Satilla coastal lowland ......................................... 36 Minor features..................................................... 38 Terraces...................................................... -

West Gulf Coastal Plain Pine

Rapid Assessment Reference Condition Model The Rapid Assessment is a component of the LANDFIRE project. Reference condition models for the Rapid Assessment were created through a series of expert workshops and a peer-review process in 2004 and 2005. For more information, please visit www.landfire.gov. Please direct questions to [email protected]. Potential Natural Vegetation Group (PNVG) R5GCPP West Gulf Coastal Plain Pine -- Uplands + Flatwoods General Information Contributors (additional contributors may be listed under "Model Evolution and Comments") Modelers Reviewers Maria Melnechuk [email protected] In worshop review Mike Melnechuk [email protected] Doug Zollner [email protected] Doug Zollner [email protected] Vegetation Type General Model Sources Rapid AssessmentModel Zones Forested Literature California Pacific Northwest Local Data Great Basin South Central Dominant Species* Expert Estimate Great Lakes Southeast Northeast S. Appalachians PITA LANDFIRE Mapping Zones PIEC Northern Plains Southwest 37 N-Cent.Rockies QUER 44 ANDR 45 Geographic Range This PNVG lies in Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and SE Oklahoma. The West Gulf Coastal Plain Pine- Hardwood Forest type is found over a large area of the South Central model zone. It is the predominate vegetation system over most of the Upper West Gulf Coastal Plain ecoregion with smaller incursions into the southern Interior Highlands (Ecological Classification CES203.378). The flatwoods communities represent predominately dry flatwoods of limited areas of the inland portions of West Gulf Coastal Plain. (Ecological Classification CES203.278) Biophysical Site Description This PNVG was historically present on nearly all uplands in the region except on the most edaphically limited sites (droughty sands, calcareous clays, and shallow soil barrens/rock outcrops). -

Alaska Peninsula and Becharof

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Alaska Peninsula and Becharof National Wildlife Refuge Bird List Covering approximately 4.6 million acres (larger than Connecticut and Rhode Island combined), the Alaska Peninsula/Becharof National Wildlife Refuge includes an immense variety of Peregrine Falcon ©Rod Cyr habitats and is home to more than 200 species of birds. Established in 1980, the Refuge conserves fish and wildlife populations and habitats in their natural diversity. Introduction The Alaska Peninsula/Becharof National Wildlife Refuge is a long, thin refuge; reaching from the Gulf of Alaska coast, over the Aleutian Mountains and a number of large inland lakes, to the middle of the Bristol Bay Coastal Plain. The Refuge stretches from the Katmai National Park’s southern boundary to American Bay on the Gulf of Alaska and Port Moller on the Bristol Bay coast, and is interrupted by Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve. Becharof Lake, completely within Becharof NWR, is the largest lake in the wildlife refuge system. The landscape is shaped by the Pacific Ocean, active volcanoes and glaciers, meandering rivers and sub- arctic weather cells. Habitats include near-shore marine, coastal shores and cliffs, alpine tundra, forest, shrub and a mostly treeless tundra/ shrubland/wetland complex at lower elevations. This diversity of the Refuge’s landforms and habitats contributes to a diverse avifauna. Starting at the Gulf of Alaska, coastal waters support a variety of seabirds, other cliff dependent species, and wintering waterfowl. The land rises sharply to the Aleutian Mountains, where alpine species of landbirds, shorebirds, cliff nesting raptors, and the elusive Kittlitz’s Murrelet find homes. -

Summary of Hydrology of the Regional Aquifer Systems, I Gulf Coastal Plain, South-Central United States

SUMMARY OF HYDROLOGY OF THE REGIONAL AQUIFER SYSTEMS, I GULF COASTAL PLAIN, SOUTH-CENTRAL UNITED STATES PROFESSIONAL PAPER I416-A science for a changing world Availability of Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey Order U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) publications from the Documents. Check or money order must be payable to the offices listed below. Detailed ordering instructions, along with Superintendent of Documents. Order by mail from prices of the last offerings, are given in the current-year issues Superintendent of Documents of the catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Government Printing Office Survey." Washington, DC 20402 Books, Maps, and Other Publications Information Periodicals By Mail Many Information Periodicals products are available through Books, maps, and other publications are available by mail the systems or formats listed below: from Printed Products USGS Information Services Box 25286, Federal Center Printed copies of the Minerals Yearbook and the Mineral Com Denver, CO 80225 modity Summaries can be ordered from the Superintendent of Publications include Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water- Documents, Government Printing Office (address above). Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Printed copies of Metal Industry Indicators and Mineral Indus Circulars. Fact Sheets, publications of general interest, single try Surveys can be ordered from the Center for Disease Control copies of permanent USGS catalogs, and topographic and and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and thematic maps. Health, Pittsburgh Research Center, P.O. Box 18070, Pitts burgh, PA 15236-0070. Over the Counter Mines FaxBack: Return fax service Books, maps, and other publications of the U.S. Geological Survey are available over the counter at the following USGS \. -

Northland Regional Landscape Assessment Worksheet

Northland Regional Landscape Assessment Worksheet Unit name – WAIKUKU BEACH TO TOM BOWLING BAY LOWLAND DESCRIPTION AND CHARACTERISATION Component Comment Land Types A broad tombolo of accumulated sand that has formed between the (refer to list overleaf) former island of North Cape headland and the mainland body. Beach Swamps and peat deposits have built up on this area as sands have Dune complex Coastal plain (tombolo) created pans and drainage is impeded. Wetlands Lakes and waterbodies Geology Holocene foredunes overlying eroded Pleistocene consolidated dune (including geopreservation sites) sand associated with Tom Bowling Bay and Waikuku Beach. Pleistocene-Holocene muddy and sandy interdune deposits on tombolo bordered by Pleistocene-Holocene foredune belts creating freshwater wetlands in muddy and sandy interdune deposits. NZ Geopres Inventory: Waikuku Beach (north) and Waikuku Beach (south) Miocene limestone sites – only marine middle or late Miocene fauna known north of Kawhia or East Cape. Waikuku Flat dune dammed swamp – a large area in the centre of the tombolo. Soil Types Te Kopuru sand, Ohia sand, Ruakaka peaty sandy loam, Hurewai fine sandy loam, Te Hapua fine sandy loam, Kapuwairua clay and silty clay, eroded remains of Red Hill sandy clay loam. Ecology Waikuku Beach is considered a good example of a nationally (including protected vegetation / features, threatened habitat type supporting threatened and regionally PNAP Level 1 and 2 sites) significant species . Tom Bowling Bay contains a diverse array of plant and animal taxa, including several threatened species within a nationally uncommon habitat type (dunefields). A range of wetland / peat favouring ecological units are developed around depressions and wet areas in the central part of the tombolo. -

Coastal Plain Marsh Community Abstract

Coastal Plain Marsh Community Abstract Community Range High water level, Goose Lake, 1990 Top photo by Michael R. Penskar Bottom photo by Dennis A. Albert Low water level, Goose Lake, 1999 Prevalent or likely prevalent Infrequent or likely infrequent Absent or likely absent Range: Coastal plain marsh is a Great Lakes Region ranges along the Atlantic and Gulf coastal plains. In wetland plant community comprised chiefly of species the upper Great Lakes Region this community occurs from the Atlantic and Gulf coastal plains. Coastal along the shores of softwater seepage lakes, ponds and plain marsh occurs on sand deposits associated with depressions where water levels fluctuate both seasonally postglacial lakes and outwash channels in southwest and yearly. Michigan and northern Indiana, northern and central Wisconsin, and the southeastern Georgian Bay region of Coastal plain marsh occurs on sandy, pitted outwash Ontario (Chapman 1990, Reznicek 1994). In southwest plains and sandy lakeplains (Chapman 1990, Kost et al. Michigan and northwestern Indiana, the greatest 2007). Similar to the Atlantic and Gulf coastal plains, concentration of coastal plain marshes is found on sand these level outwash plains and abandoned glacial deposits associated with postglacial stages of Lake lakebeds harbor shallow depressions with gently sloping Michigan (Reznicek 1994). sides (Brodowicz 1989, Chapman 1990). Where these depressions reach groundwater and the sandy substrate Global and State Rank: G2/S2 is acidic, coastal plain marsh may occur. The sandy soils underlying coastal plain marsh are strongly to Rank Justification: Coastal plain marshes are rare in very strongly acidic and nutrient poor. Organic deposits the Great Lakes Region and typically occur as small of peat, muck, or sandy peat may overlay the sandy (e.g., less than 50 acres), isolated depressions. -

The United States and Canada

The United States and Canada Physical Geography Landforms The U.S. and Canada have several major mountain ranges: A. The Rocky Mountains B. The Appalachian Mountains C. Pacific Coastal Ranges The Rocky Mountains The Rocky Mountains extend about 3,000 miles from Alaska south to New Mexico. They are younger and taller than the Appalachian Mountains. The Continental Divide is the line of highest points in the Rockies that marks the separation of rivers flowing eastward and westward. The Appalachian Mountains The Appalachian Mountains extend about 1,600 miles north to south from Newfoundland in Canada to Alabama. Pacific Coastal Ranges A series of small mountain ranges stretch from southern California to Washington. These ranges are low in elevation and right on the coast. They make the coastline rugged and steep. This area is also on the Ring of Fire and has many active and dormant volcanoes. Earthquakes are common in this area. Other Landforms A. The Canadian Shield B. Interior Lowlands C. Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plains D. Basin and Range E. Great Plains F. Grand Canyon Canadian Shield The Canadian Shield is a rocky, mainly flat area around Hudson Bay. Interior Lowlands An area that spreads from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River. This area is mostly flat with rolling hills. Arctic and Gulf Coastal Plains These are flat areas that stretch along the Gulf of Mexico in the south and the Arctic Ocean in the north. The Arctic Coastal Plain is tundra. Basin and Range This area is mostly in Nevada and it consists of rocky outcroppings of rock and large depressions. -

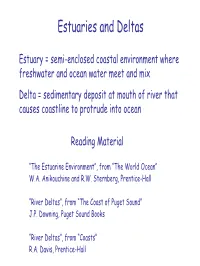

Estuaries and Deltas

Estuaries and Deltas Estuary = semi-enclosed coastal environment where freshwater and ocean water meet and mix Delta = sedimentary deposit at mouth of river that causes coastline to protrude into ocean Reading Material “The Estuarine Environment”, from “The World Ocean” W.A. Anikouchine and R.W. Sternberg, Prentice-Hall “River Deltas”, from “The Coast of Puget Sound” J.P. Downing, Puget Sound Books “River Deltas”, from “Coasts” R.A. Davis, Prentice-Hall Impact of sea-level rise on fluvial and glacial valleys 20,000 y to 7,000 y ago valleys flooded, all sediment trapped 7,000 y ago to present if little sediment supply – estuaries and fjords still filling trapping mechanisms very important (Chesapeake Bay) if moderate sediment supply – estuaries nearly full some sediment leaks to continental shelf (Columbia River) if much sediment supply – estuaries full and sediment overflowing deltas build seaward (Mississippi Delta) Chesapeake and Delaware Bays Coastal-Plain Estuaries Drowned river valleys Impact of sea-level rise on fluvial and glacial valleys 20,000 y to 7,000 y ago valleys flooded, all sediment trapped 7,000 y ago to present if little sediment supply – estuaries and fjords still filling trapping mechanisms very important (Chesapeake Bay) if moderate sediment supply – estuaries nearly full some sediment leaks to continental shelf (Columbia River) if much sediment supply – estuaries full and sediment overflowing deltas build seaward (Mississippi Delta) Some sediment from Columbia River escapes estuary and accumulates on the adjacent