Geographies of India-Nepal Contestation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory Establishment

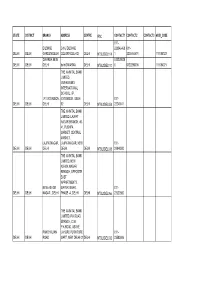

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :URBAN STATE : UTTARANCHAL DISTRICT : Almora Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 MILITARY DAIRY FARM RANIKHET ALMORA , PIN CODE: 263645, STD CODE: 05966, TEL NO: 222296, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 1962 10 - 50 NIC 2004 : 1520-Manufacture of dairy product 2 DUGDH FAICTORY PATAL DEVI ALMORA , PIN CODE: 263601, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL 1985 10 - 50 : N.A. NIC 2004 : 1549-Manufacture of other food products n.e.c. 3 KENDRYA SCHOOL RANIKHE KENDRYA SCHOOL RANIKHET ALMORA , PIN CODE: 263645, STD CODE: 05966, TEL NO: 1980 51 - 100 220667, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 1711-Preparation and spinning of textile fiber including weaving of textiles (excluding khadi/handloom) 4 SPORTS OFFICE ALMORA , PIN CODE: 263601, STD CODE: 05962, TEL NO: 232177, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 1975 10 - 50 NIC 2004 : 1725-Manufacture of blankets, shawls, carpets, rugs and other similar textile products by hand 5 PANCHACHULI HATHKARGHA FAICTORY DHAR KI TUNI ALMORA , PIN CODE: 263601, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, 1992 101 - 500 E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 1730-Manufacture of knitted and crocheted fabrics and articles 6 HIMALAYA WOLLENS FACTORY NEAR DEODAR INN ALMORA , PIN CODE: 203601, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, 1972 10 - 50 E-MAIL : N.A. -

We Take Pride in Jobs Well Done

We take pride in jobs well done. JAGADAMBA PRESS #128 17 - 23 January 2003 16 pages Rs 25 [email protected] Tel: (01) 521393, 543017, 547018 Fax: (01) 536390 HEMLATA RAI, with JANAK NEPAL Manjushree in ○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○ NEPALGANJ hoever killed their parents, the talks to Samrat children end up in the same place. W Sangita Yadav’s father was a farmer in Leave the kids alone Banke district. The Maoists came while he was the needs of those who are already affected.” Children recruited by eating, dragged him out of his house, beat and One of the undocumented aspects of the tortured him in front of his family, and killed Maoists to carry their conflict is the growing number of internally him. Sarala Dahal’s father was a teacher in the rucksacks rest at a tea displaced families. This has increased the same district. He was killed after surrendering house in Kalikot number of children in the district headquarters, to the security forces. district in June. townships and in Kathmandu Valley who have Sarala and Sangita are both being raised in a lost their traditional village support Novelist Manjushree Thapa, author of the child shelter which has just opened in mechanisms. School closures and threats of much-acclaimed The Tutor of History has Nepalganj by the charity group, Sahara. “We forced recruitment of one child per family by a cyber-chat with fellow-author and don’t really care who killed their parents or Maoists have added to the influx of children. A compatriot, Samrat Upadhyay who has relatives, we want to protect the future of these recent survey in the insurgency hotbed of just published his second book, The Guru children, and they all get equal care here,” says Rukum alone found that out of 1,000 people of Love in the United States. -

La”Kksf/Kr Vkns”K

la”kksf/kr vkns”k Incident Response System (IRS) for District Disaster Management in District Pithoragarh vkink izcU/ku vf/kfu;e 2005 v/;k; IV dh /kkjk 28 dh mi/kkjk 01 ds vUrxZr o`ºr vkinkvksa ds nkSjku tuin fiFkkSjkx<+ esa vkink izcU/ku izkf/kdj.k ds vUrxZr iwoZ esa xfBr fuEuor Incident Response System (IRS) dks fuEu izdkj leLr vkinkvksa gsrq fØ;kfUor fd;k tkrk gSaA S.N. Position of IRS Nomination in IRS 1. Responsible Officer (RO) District Magistrate (DM) Pithoragarh 05964-225301,225441, 9410392121, 7579162221 1.1 Deputy Responsible Officer (DRO) ADM/CDO/ Officer Next to DM 2.0 COMMAND STAFF (CS) 2.1 Incident Commander (IC) Superintendent of Police (SP) Pithoragarh 05964-225539, 225023, 9411112082 2.2 Information & Media Officer (IMO) District Information Officer (DIO) Pithoragarh, 05964-225549, 9568171372, 9412908675 NIC Officer Pithoragarh 05964-224162, 228017, 9412952098 2.3 Liaison Officer (LO) District Disaster Management Officer (DDMO) 05964-226326,228050, 9412079945, 8476903864 SDM (Sadar) Pithoragarh 05964-225950, 9411112595 2.4 Safety Officer (SO) SO Police 05964-225238, 9411112888 SDO forest 9410156299 FSO Pithoragarh as per Specific Requirement 05964-225314, 9411305686 3.0 OPERATION SECTION (OS) 3.1 Operation Section Chief (OSC) SP Pithoragarh 9411112082 DSP Pithoragarh 9411111955 DFO Pithoragarh (For Forst Fire) 05964-225234, 225390, 9410503638 CMO Pithoragarh (For Epidemics) 05964-225142,225504, 9837972600, 7310801479 3.2.1 Staging Area Manager (SAM) CO Police Pithoragarh 05964-225539, 225410, 941111955 RI Police line -

District Profile Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand

District Profile Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand The district of Pithoragarh lies in the north-eastern boundary of the newly created state Uttarakhand. The district has been divided into six tehsils namely Munsari, Dharchula, Didihat, Gangolihat, Berinag and Pithoragarh as per Census 2011. This has been further divided into eight community development blocks. There are 1572 inhabited and 103 un-inhabited villages and 669 Gram Panchayat in the district. The towns are Dharchula NP, Didihat NP, and Pithoragarh NPP. DEMOGRAPHY As per Census 2011, the total population of Pithoragarh is 483,439. Out of which 239,306 were males and 244,133 were females. This gives a sex ratio of 1020 females per 1000 males. The percentage of urban population in the district is 14.40 percent, which is almost half the state average of 30.23 percent. The deca- dal growth rate of population in Uttarakhand is 18.81 percent, while Pithoragarh reports a 4.58 percent decadal increase in the population. The decadal growth rate of urban population in Uttarakhand is 39.93 percent, while Pithoragarh reports a 16.33 percent. The district population density is 68 in 2011. The Sched- uled Caste population in the district is 24.90 percent while Scheduled Tribe comprises 4.04 percent of the population. LITERACY The overall literacy rate of Pithoragarh district is 82.25 percent while the male & female literacy rates are 92.75 percent and 72.29 percent respectively. At the block level, a considerable variation is noticeable in male-female literacy rate. Munsiari block has the lowest literacy male and female rates at 88.55 percent and 62.66 percent respectively. -

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: a Newar Perspective

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: A Newar Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Tsukuba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Public Policy Suwarn VAJRACHARYA 2014 To my mother, who taught me the value in a mother tongue and my father, who shared the virtue of empathy. ii Map-1: Original Nepal (Constituted of 12 districts) and Present Nepal iii Map-2: Nepal Mandala (Original Nepal demarcated by Mandalas) iv Map-3: Gorkha Nepal Expansion (1795-1816) v Map-4: Present Nepal by Ecological Zones (Mountain, Hill and Tarai zones) vi Map-5: Nepal by Language Families vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents viii List of Maps and Tables xiv Acknowledgements xv Acronyms and Abbreviations xix INTRODUCTION Research Objectives 1 Research Background 2 Research Questions 5 Research Methodology 5 Significance of the Study 6 Organization of Study 7 PART I NATIONALISM AND LANGUAGE POLITICS: VICTIMS OF HISTORY 10 CHAPTER ONE NEPAL: A REFLECTION OF UNITY IN DIVERSITY 1.1. Topography: A Unique Variety 11 1.2. Cultural Pluralism 13 1.3. Religiousness of People and the State 16 1.4. Linguistic Reality, ‘Official’ and ‘National’ Languages 17 CHAPTER TWO THE NEWAR: AN ACCOUNT OF AUTHORS & VICTIMS OF THEIR HISTORY 2.1. The Newar as Authors of their history 24 2.1.1. Definition of Nepal and Newar 25 2.1.2. Nepal Mandala and Nepal 27 Territory of Nepal Mandala 28 viii 2.1.3. The Newar as a Nation: Conglomeration of Diverse People 29 2.1.4. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE 011- DILSHAD C-16, DILSHAD 223546460 011- DELHI DELHI GARDEN DELHI COLONY DELHIQ DELHI NTBL0DEL114 1 2235464601 110184023 DWARKA NEW 512228030 DELHI DELHI DELHI delhi DWARKA DELHI NTBL0DEL110 0 5122280300 110184021 THE NAINITAL BANK LIMITED, VIVEKANAND INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL, I.P. I.P. EXTENSION, EXTENSION, DELHI 011- DELHI DELHI DELHI 92 DELHI NTBL0DEL053 22240041 THE NAINITAL BANK LIMITED, LAJPAT NAGAR BRANCH, 40- 41, PUSHPA MARKET, CENTRAL MARKET, LAJPATNAGAR, LAJPATNAGAR, NEW 011- DELHI DELHI DELHI DELHI DELHI NTBL0DEL038 29848500 THE NAINITAL BANK LIMITED, NEW ASHOK NAGAR BRANCH, OPPOSITE EAST APPARTMENTS, NEW ASHOK MAYUR VIHAR, 011- DELHI DELHI NAGAR , DELHI PHASE -A, DELHI DELHI NTBL0DEL066 22622800 THE NAINITAL BANK LIMITED, P.K.ROAD BRANCH, C-36, P.K.ROAD, ABOVE PANCHKUIAN LAHORE FURNITURE 011- DELHI DELHI ROAD MART, NEW DELHI 01 DELHI NTBL0DEL032 23583606 THE NAINITAL BANK LIMITED, PAPPANKALAN BRANCH, 29/2, VIJAY ENCLAVE, PALAM PAPPANKALAN( DABRI ROAD, KAPAS 011- DELHI DELHI DWARKA) DWARKA, DELHI HERA NTBL0DEL059 25055006 THE NAINITAL BANK LIMITED, PATPARGANJ BRANCH, P-37, PANDAV NAGAR, 011- DELHI DELHI PATPARGANJ PATPARGANJ, DELHI DELHI NTBL0DEL047 22750529 THE NAINITAL BANK LIMITED, PITAMPURA BRANCH, SATABDI HOUSE, PLOTNO. 3, COMMERCIAL COMPLEX, ROHIT KUNJ, WEST PITAMPURA , PITAMPURA 110034, 011- DELHI DELHI DELHI DELHI DELHI NTBL0DEL049 27353273 THE NAINITAL BANK LIMITED, ROHINI BRANCH, E-4, SECTOR 16, JAIN BHARTI MODEL, PUBLIC SCHOOL, ROHINI, ROHINI, -

Mainstream Religious Domain in Nepal a Contradiction and Conflict

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Electronic Sumy State University Institutional Repository SocioEconomic Challenges, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2019 ISSN (print) – 2520-6621, ISSN (online) – 2520-6214 Mainstream Religious Domain in Nepal a Contradiction and Conflict of Indigenous Communities in Maintaining the Identity, Race, Gender and Class https://doi.org/10.21272/sec.3(1).99-115.2019 Medani P. Bhandari PhD, Professor and Deputy Program Director of Sustainability Studies, Akamai University, Hawaii, USA, Professor of Economics and Entrepreneurships, Sumy State University, Ukraine Nepal is certainly one of the more romanticized places on earth, with its towering Himalayas, its abomi- nable snowmen, and its musically named capital, Kathmandu, a symbol of all those faraway places the imperial imagination dreamt about. And the Sherpa people ... are perhaps one of the more romanticized people of the world, renowned for their mountaineering feats, and found congeal by Westerners tour their warm, friendly, strong, self-confident style" (Sherry Ortner, 1978: 10). “All Nepalese, whether they realize it or not, are immensely sophisticated in their knowledge and appreciation cultural differences. It is a rare Nepalese indeed who knows how to speak only one language” (James Fisher 1987:33). Abstract Nepal is unique in terms of culture, religion, and geography as well as in its Indigenous Communities (IC). There has always been domination by the mainstream culture and religion; however, until recently there was no visible friction and violence between any religious groups and ICs. Within the societal structure, there was an effort to maintain harmonious relationships, at least on the surface. -

Geological and Geotechnical Characterisation of the Khotila Landslide in the Dharchula Region, NE Kumaun Himalaya

J. Earth Syst. Sci. (2019) 128:86 c Indian Academy of Sciences https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-019-1106-9 Geological and geotechnical characterisation of the Khotila landslide in the Dharchula region, NE Kumaun Himalaya Ambar Solanki1,VikramGupta1,*, S S Bhakuni1, Pratap Ram1 and Mallickarjun Joshi2 1Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, 33 General Mahadeo Singh Road, Dehradun 248 001, Uttarakhand, India. 2Department of Geology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. *Corresponding author. e-mail: vgupta [email protected] MS received 18 April 2018; revised 6 August 2018; accepted 21 August 2018; published online 22 March 2019 On 04 October 2016, a severe landslide had occurred in the vicinity of Khotila village in Dharchula, region of NE Kumaun Himalaya. This landslide may be classified as typical rockslide, involving thin veneer of debris on the slope as well as the highly shattered rockmass. The slide has been divided into three morpho-dynamic zones, viz., (i) Zone of detachment between elevation 1000 and 960 m, (ii) Zone of transportation between elevation 960 and 910 m, and (iii) Zone of accumulation between elevation 910 and 870 m. The landslide had occurred at the end of the monsoon season when the slope was completely saturated. It has been noted that the area received ∼88% rainfall during the monsoon months which is about two times more rainfall during 2016 monsoon than during 2015 monsoon. Geotechnical testing of the soil overlying the rockmass, corroborate the soil as ‘soft soil’ with compressive strength of 42 kPa and friction angle of 27.4◦. Granulometry confirms the soil as having >97% sand and silt size particles and <3% clay size particles, indicating higher permeability. -

Cfreptiles & Amphibians

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES &IRCF AMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 189 24(3):197–200 • DEC 2017 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES New. Chasing Bullsnakes Distributional (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: Records for the On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: HimalayanA Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................ White-lipped Pitviper,Robert W. Henderson 198 TrimeresurusRESEARCH ARTICLES septentrionalis Kramer 1977 . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in Florida (Reptilia: ............................................. Viperidae)Brian J. Camposano, Kenneth L. Krysko, Kevinfrom M. Enge, Ellen M. theDonlan, and MichaelGarhwal Granatosky 212 CONSERVATION ALERT . World’sHimalaya Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................... in Northwestern ..............................India 220 . More Than Mammals ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

India L M S Palni, Director, GBPIHED

Lead Coordinator - India L M S Palni, Director, GBPIHED Nodal Person(s) – India R S Rawal, Scientist, GBPIHED Wildlife Institute of India (WII) G S Rawat, Scientist Uttarakhand Forest Department (UKFD) Nishant Verma, IFS Manoj Chandran, IFS Investigators GBPIHED Resource Persons K Kumar D S Rawat GBPIHED Ravindra Joshi S Sharma Balwant Rawat S C R Vishvakarma Lalit Giri G C S Negi Arun Jugran I D Bhatt Sandeep Rawat A K Sahani Lavkush Patel K Chandra Sekar Rajesh Joshi WII S Airi Amit Kotia Gajendra Singh Ishwari Rai WII Merwyn Fernandes B S Adhikari Pankaj Kumar G S Bhardwaj Rhea Ganguli S Sathyakumar Rupesh Bharathi Shazia Quasin V K Melkani V P Uniyal Umesh Tiwari CONTRIBUTORS Y P S Pangtey, Kumaun University, Nainital; D K Upreti, NBRI, Lucknow; S D Tiwari, Girls Degree College, Haldwani; Girija Pande, Kumaun University, Nainital; C S Negi & Kumkum Shah, Govt. P G College, Pithoragarh; Ruchi Pant and Ajay Rastogi, ECOSERVE, Majkhali; E Theophillous and Mallika Virdhi, Himprkrthi, Munsyari; G S Satyal, Govt. P G College Haldwani; Anil Bisht, Govt. P G College Narayan Nagar CONTENTS Preface i-ii Acknowledgements iii-iv 1. Task and the Approach 1-10 1.1 Background 1.2 Feasibility Study 1.3 The Approach 2. Description of Target Landscape 11-32 2.1 Background 2.2 Administrative 2.3 Physiography and Climate 2.4 River and Glaciers 2.5 Major Life zones 2.6 Human settlements 2.7 Connectivity and remoteness 2.8 Major Land Cover / Land use 2.9 Vulnerability 3. Land Use and Land Cover 33-40 3.1 Background 3.2 Land use 4. -

List of Polling Station for 42-Dharchula(GEN) Assembly

List of Polling Station for 42-Dharchula(GEN) Assembly Constituency Comprised with in the 3-Almora(SC) Parliamentary Constituencies District-Pithoragarh SL.NO Locality of Polling Building in which it will be Area of the Polling Station Whether for all voter or Station Located man only or woman only 1 2 3 4 5 1 Pato Govt. Primary school 1- Bui For All 2- Panto 3- Leelam 2 Saipolu Govt. Primary school 1- Saipolu For All 2- Saibhat 3- Qwiri 4- Jimiya 3 Jainti Govt. Primary school 1- Jainti For All 2- Sankhdhura 3- Sarmoli 4- Suring 4 Tiksen Govt. Adrsh Vidyalya 1- Bunga For All 5 Tiksen Govt. Primary school 1- Ghorpatta Malla For All 2- Ghorpatta Talla 6 Dhapa Govt. Primary school 1- Pyangti For All 2- Sainar 3- Dhapa 7 Darkot Govt. Primary school 1- jalath For All 2- Darkot 3- DuMmar Malla 4- Dummar Talla 8 Darati Govt. Primary school 1- Darati For All 2- Ranthi 3- Minalgaon 4- Nagariyabara 5- Diyawalla 6- Diyapalla 7- Khasiyabara 8- Gopalbara 9- Charklham 10- Matiyali 9 Kawadhar Govt. Primary School 1- Jubuk For All 2- Barniyagaon 3- Ghatdhar 4- Kawadhar 5- Sela 6- SelaChital 7- Sela Malla 8- Kholi 9- Dhamikura 10- Manachulnkar 11- Namjala 12- Chetichimla Page 1 of 9 List of Polling Station for 42-Dharchula(GEN) Assembly Constituency Comprised with in the 3-Almora(SC) Parliamentary Constituencies District-Pithoragarh SL.NO Locality of Polling Building in which it will be Area of the Polling Station Whether for all voter or Station Located man only or woman only 1 2 3 4 5 10 Sevila Govt. -

Directory of E-Mail Accounts of Uttarakhand Created on NIC Email Server

Directory of E-mail Accounts of Uttarakhand Created on NIC Email Server Disclaimer : For email ids enlisted below, the role of NIC Uttarakhand State Unit is limited only as a service provider for technical support for email-ids created over NIC’s Email Server, over the demand put up by various Government Depratments in Uttarakhand from time to time. Therefore NIC does not take responsibility on how an email account is used and consequences of it’s use. Since there may also be a possibility that these Departments might be having varied preferences for using email ids of various service providers (such as yahoo, rediffmail, gmail etc etc) other than NIC email ids for various official purposes. Therefore before corresponding with an email over these accounts, it is advised to confirm official email account directly from the department / user. As per policy NIC's email account once not used continuously for 90 days gets disabled. Last Updated on :- 25/10/2012 DEPARTMENT DESIGNATION HQs EMAIL-ID DESCRIPTION Accountant General Accountant General State Head Quarter [email protected] Accountant General(A & E) Agriculture Hon'ble Minister State Head Quarter [email protected] Minister of Agriculture, GoU Agriculture Secretary State Head Quarter [email protected] Secretary, GoUK Aditional Director of Agriculture Aditional Director State Head Quarter [email protected] Agriculture,Dehradun,Uttarakhand Deputy Director Technical Analysis of Agriculture Deputy Director State Head Quarter [email protected] Agriculture ,Dehradun,Uttarakhand Deputy