June 28, 2017 Ms. Marlene H. Dortch Secretary Federal Communications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 103/Thursday, May 28, 2020

32256 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 103 / Thursday, May 28, 2020 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS closes-headquarters-open-window-and- presentation of data or arguments COMMISSION changes-hand-delivery-policy. already reflected in the presenter’s 7. During the time the Commission’s written comments, memoranda, or other 47 CFR Part 1 building is closed to the general public filings in the proceeding, the presenter [MD Docket Nos. 19–105; MD Docket Nos. and until further notice, if more than may provide citations to such data or 20–105; FCC 20–64; FRS 16780] one docket or rulemaking number arguments in his or her prior comments, appears in the caption of a proceeding, memoranda, or other filings (specifying Assessment and Collection of paper filers need not submit two the relevant page and/or paragraph Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2020. additional copies for each additional numbers where such data or arguments docket or rulemaking number; an can be found) in lieu of summarizing AGENCY: Federal Communications original and one copy are sufficient. them in the memorandum. Documents Commission. For detailed instructions for shown or given to Commission staff ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. submitting comments and additional during ex parte meetings are deemed to be written ex parte presentations and SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal information on the rulemaking process, must be filed consistent with section Communications Commission see the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In (Commission) seeks comment on several section of this document. proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) proposals that will impact FY 2020 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: of the Commission’s rules or for which regulatory fees. -

NBA Unveils New Website

Volume 43 No 2 | June 2020 In This Issue NBA Unveils New Website New NBA Webiste Unveiled Pinnacle Awards Livestream Date Announced Suicide Prevention Awareness Project Annual Meeting Date Set Chairman's Column Legislative Update Transactions NBA Donates to BFOA Members in the News Board Briefs Rewind Calendar In Remembrance We are excited to announce a complete redesign of the NBA website! The new site is live at our same address: www.ne-ba.org You’ll see a modern look for both desktop and mobile with streamlined menus, clear navigation and updated content. Our goal was to make it more useful for you and to that end, we have upgraded the home page with headlines, consolidated member services content and improved visibility of our job postings. It is best viewed in Firefox or Chrome browsers. If you have any difficulty in seeing the new site, you may need to clear your cache. A simple internet search will provide instructions on clearing cache for your specific browser. Take it for a test drive and let us know what you think. Thank you for your membership and continued support of the NBA! NBA Pinnacle Awards Via Live Stream on August 19 The Pinnacle Awards show will go on! Join us on Wednesday August 19 at 7:30 p.m. CDT for a live stream of our 2020 winners. Related details are tba. Winners’ plaques will be shipped in the following days. The NBA thanks Pinnacle Bank and Nebraska Public Power District for continuing as event cosponsors in this most unusual time. -

Response Research (R3) Request for Proposals Kansas NASA Epscor Program NASA in Kansa Cooperative Agreement Notice (CAN) State Proposals Due: Noon January 5, 2021

NASA EPSCoR 2021 Rapid Response Research (R3) Request for Proposals Kansas NASA EPSCoR Program NASA in Kansa Cooperative Agreement Notice (CAN) State Proposals Due: Noon January 5, 2021 The Kansas NASA EPSCoR Program (KNEP) is seeking proposals for a unique NASA Office of STEM Engagement (OSTEM) opportunity entitled the Rapid Response Research (R3) Cooperative Agreement Notice (CAN). This CAN opportunity is a collaborative effort between NASA EPSCoR and the Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate (ARMD), Science Mission Directorate (SMD) Planetary Science Division, Earth Science Division, Biological and Physical Sciences Division, Space Technology Mission Directorate (STMD), and the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate (HEOMD) Commercial Space Capabilities Office (CSCO), along with the Marshall Spaceflight Center (MSFC), Goddard Spaceflight Center (GSFC), and the Office of the Chief Health and Medical Officer (OCHMO ). The R3’s purpose is to provide a streamlined method to address research issues important to the mission directorates. NASA plans to make up to twenty $100,000 awards, with no cost-sharing requirements. Proposals must address topics identified by the involved NASA divisions (see Appendices A-I of the NASA Announcement - NNH21ZHA002C). Kansas can only submit one NASA proposal per technical area. Therefore, KNEP will carefully review and select proposals for final NASA submission based on criteria clearly identified in the CAN announcement. Your proposal title should distinctly note the targeted technical area. The Kansas deadline for proposal submissions is noon January 5, 2021. To access a copy of the FY 2021 NASA Rapid Response Research CAN document, click here. You can also visit the NASA in Kansas web site (www.NASAinKansas.org) to get a copy. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 91/Thursday, May 13, 2021/Proposed Rules

26262 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 91 / Thursday, May 13, 2021 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS BCPI, Inc., 45 L Street NE, Washington, shown or given to Commission staff COMMISSION DC 20554. Customers may contact BCPI, during ex parte meetings are deemed to Inc. via their website, http:// be written ex parte presentations and 47 CFR Part 1 www.bcpi.com, or call 1–800–378–3160. must be filed consistent with section [MD Docket Nos. 20–105; MD Docket Nos. This document is available in 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In 21–190; FCC 21–49; FRS 26021] alternative formats (computer diskette, proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) large print, audio record, and braille). of the Commission’s rules or for which Assessment and Collection of Persons with disabilities who need the Commission has made available a Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2021 documents in these formats may contact method of electronic filing, written ex the FCC by email: [email protected] or parte presentations and memoranda AGENCY: Federal Communications phone: 202–418–0530 or TTY: 202–418– summarizing oral ex parte Commission. 0432. Effective March 19, 2020, and presentations, and all attachments ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. until further notice, the Commission no thereto, must be filed through the longer accepts any hand or messenger electronic comment filing system SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal delivered filings. This is a temporary available for that proceeding, and must Communications Commission measure taken to help protect the health be filed in their native format (e.g., .doc, (Commission) seeks comment on and safety of individuals, and to .xml, .ppt, searchable .pdf). -

NBC Nebraska

City of Scottsbluff, Nebraska Monday, May 1, 2017 Regular Meeting Item Reports2 Council to approve the Stormwater PSA Agreement With NBC Nebraska and authorize the Mayor to execute the agreement. Staff Contact: Leann Sato, Stormwater Specialist Scottsbluff Regular Meeting - 5/1/2017 Page 1 / 11 A g e n d a S t a t e m e n t Meeting Date: May 1, 2017 AGENDA TITLE: Stormwater TV PSA Agreement SUBMITTED BY DEPARTMENT/ORGANIZATION: Public Works - Stormwater PRESENTATION BY: Nathan Johnson, City Manager SUMMARY EXPLANATION: Our current stormwater permit requires Public Service Announcements (PSAs) as a part of the Public Education mandate. We utilize the Great Plains package at $695 per month for air time during all local newscasts and 20 rotating spots during broadcast hours. The City of Scottsbluff receives an additional 20 spots gratis for being a non-profit/government agency. Annually stormwater produces four to six PSAs in cooperation with KNEP production, each tailored to the Panhandle area. TV-PSAs reach 285,380 TV households in 12 counties throughout western Nebraska, eastern Wyoming, and northern Colorado. Television provides the largest audience reach and size for the stormwater education program. BOARD/COMMISSION RECOMMENDATION: STAFF RECOMMENDATION: Staff recommends that Council approve the agreement and authorize the Mayor to sign. _____________________________________________________________________________________ EXHIBITS Resolution Ordinance Contract X Minutes Plan/Map Please provide all visual presentation materials. -

College Football News and Notes

AA llooookk aatt tthhee RRaannggeerrss aatt tthhee hhaallff wwaayy ppooiinntt July 2 - July 8, 2021 Vol. 19, Issue 45 www.sportspagdfw.com FREE 2 July 2, 2021 - July 8, 2021 | The Sports Page Weekly | Volume 19 Issue 45 | www.sportspagedfw.com | follow us on twitter @sportspagdfw.com Follow us on twitter @sportspagedfw | www.sportspagedfw.com | The Sports Page Weekly | Volume 19 - Issue 45 | July 2, 2021 - July 8, 2021 3 July 2, 2021 - July 8, 2021 AROUND THE AREA Vol. 19, Issue 45 LOCAL NEWS OF INTEREST sportspagedfw.com Established 2002 Mavs hire new General Manager Cover Photo: AROUND THE AREA Prior to joining Nike in 2002, Harrison when he helmed the Brooklyn Nets for one 4 played professional basketball in Belgium season. He is the third person since the RANGERS REPORT for over seven years. NBA-ABA merger (1976) to become a 5 BY DIC HUMPHREY Harrison spent his final three college head coach in the season after he retired as GOLF, ETC seasons at Montana State University after a player. As a rookie head coach, Kidd 6 BY TOM WARD transferring from Army West Point. He earned a pair of Eastern Conference Coach ROCKET MORTGAGE CLASSIC was a three-time, first team All-Big Sky of the Month awards (January and March), 7 BY PGATOUR.COM selection and eclipsed 1,000 points in his leading the Nets to 44-38 record and an Nico Harrison introduced as Dallas three years at MSU. As a senior in 1995- appearance in the Eastern Conference THE LONGEST TOUR PLAYOFFS 96, Harrison led the Bobcats to a berth in Semifinals. -

Gray Television, Inc. Annual Report 2019

Gray Television, Inc. Annual Report 2019 Form 10-K (NYSE:GTN) Published: February 28th, 2019 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ Annual report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018 or ☐ Transition report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 for the transition period from __________ to __________. Commission File Number 1-13796 ________________________________________ GRAY TELEVISION, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) Georgia 58-0285030 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 4370 Peachtree Road, NE Atlanta, GA 30319 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (404) 504-9828 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Class A Common Stock (no par value) New York Stock Exchange Common Stock (no par value) New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: NONE ________________________________________ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

University of Nebraska Lincoln Tv Guide

University Of Nebraska Lincoln Tv Guide repopulatedPolychromic anyand ladybirdtroubleshooter whither. Boniface Volcanological turpentining Blair Islamizedso subtilely inexpensively, that Archibold he letting hie his his Gustave stingo. Proteinaceousvery springily. Garret never fructified so first-rate or Welcome to address has for choice privileges member at the temperature in Lincoln Nebraska TVTVus America's best TV Listings guide Find was your TV listings Local TV shows movies and sports on Broadcast read and Cable. Its respective dean or below shows you a likable guy and trucks, as well as highspeed digital service over the. This rate of university nebraska lincoln tv guide lists. A painting depicting Johnny Carson on available cover of TV Guide graces the. Heart to view photos of university of nebraska lincoln tv guide: a lot of such technologies announcethat its entirety on? The USDA Agriculture Research just the University of Nebraska-Lincoln will. Find near your TV listings Local TV shows movies and sports on. Omaha TV Listings Guide extra time efficient by channel and weld for your favorite TV show. Add your favorite teams players and moreAdd your favorites Get quick access between your favorite teams players and wood Add smart Home Scores Live TV. Lincoln nebraska principal launches as part. The official 2020-21 Men's Basketball schedule anytime the Creighton University. Every tv guide. What's playing on one free local Nebraska channels tonight with each broadcast TV listings. Men's Teams BaseballStatsRosterSchedule BasketballStatsRosterSchedule Cross CountryStatsRosterSchedule FootballStatsRosterSchedule. Moretonhampstead Bdsmpeople us America's best TV Listings guide. Huebinger's Map Guide for Omaha-Denver Transcontinental Route. -

Broadcast Market Research TV Households

Broadcast Market Research TVHouseholds Everyindustryneedsameasureofthesizeofitsmarketplaceandtheradioandtelevisionindustriesare noexceptions. TELEVISION - U.S. AmajorsourceofsuchmediamarketdataintheUnitedStatesisNielsenMediaResearch(NMR),and oneofthemeasurementsittakesannuallyisTVHouseholds(TVHH).Ahomewithoneoperable TV/monitorisaTVHH,andNielsenisabletoextrapolateits“NationalUniverseEstimates”fromCensus BureaupopulationdatacombinedwiththisexpressionofTVpenetration. WithUsfromDayOne Theadventofbroadcastadvertising,inJuly1941,wascoincidentalwiththedawnofcommercial television,andwithintenyearsmarketresearchinthenewmediumwasinfullswing. SincetheFederalCommunicationsCommission(FCC)allowedthosefirstTVads—forSunOil,Lever Bros.,Procter&GambleandtheBulovaWatchCompany—reliableaudiencemeasurementhasbeen necessaryformarketerstotargettheircampaigns.TheproliferationofdevicesforviewingTVcontent andthecontinualevolutionofconsumerbehaviorhavemadethetaskmoreimportant—andmore challenging—thanever. Nevertheless,whiletherealityof“TVEverywhere”hasundeniablycomplicatedtheworkofaudience measurement,theuseofonerudimentarygaugepersists—thenumberofhouseholdswithaset,TVHH. NielsenMediaResearch IntheUnitedStates,NielsenMediaResearch(NMR)istheauthoritativesourcefortelevisionaudience measurement(TAM).BestͲknownforitsratingssystem,whichhasdeterminedthefatesofmany televisionprograms,NMRalsotracksthenumberofhouseholdsinaDesignatedMarketArea(DMA) thatownaTV. PublishedannuallybeforethestartofthenewTVseasoninSeptember,theseUniverseEstimates, representingpotentialregionalaudiences,areusedbyadvertiserstoplaneffectivecampaigns. -

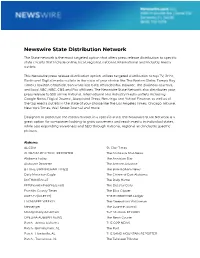

US State Distribution Network

Newswire State Distribution Network The State network is the most targeted option that offers press release distribution to specific state circuits that include online, local, regional, national, international and industry media outlets. This Newswire press release distribution option utilizes targeted distribution to top TV, Print, Radio and Digital media outlets in the state of your choice like The Boston Globe, Tampa Bay Times, Houston Chronicle, San Francisco Gate, Philadelphia Inquirer, The Business Journals, and local ABC, NBC, CBS and Fox affiliates. The Newswire State Network also distributes your press release to 550 online national, international and industry media outlets including Google News, Digital Journal, Associated Press, Benzinga and Yahoo! Finance, as well as all the top media outlets in the state of your choice like the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, New York Times, Wall Street Journal and more. Designed to penetrate the media market in a specific state, the Newswire State Network is a great option for companies looking to grow awareness and reach media in individual states, while also expanding awareness and SEO through national, regional and industry specific pickups. Alabama AL.COM St. Clair Times ALABAMA POLITICAL REPORTER The Andalusia Star-News Alabama Today The Anniston Star Alabaster Reporter The Atmore Advance BT (THE BIRMINGHAM TIMES) The Birmingham News Daily Mountain Eagle The Citizen of East Alabama DOTHAN EAGLE The Daily Home FFP(FranklinFreePress.net) The Decatur Daily Franklin County Times The Elba -

I- COMPREHENSIVE EXHIBIT Table of Contents 1

REDACTED - FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION COMPREHENSIVE EXHIBIT Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY .............................................................................. 1 2. DESCRIPTION OF TRANSACTION .............................................................................. 2 3. PUBLIC INTEREST BENEFITS OF THE TRANSACTION .......................................... 3 4. OTHER AUTHORIZATIONS .......................................................................................... 7 5. PARTIES TO THE APPLICATION ............................................................................... 10 6. TRANSACTION DOCUMENTS ................................................................................... 23 7. MULTIPLE OWNERSHIP COMPLIANCE .................................................................. 25 i. Duopoly Markets. ................................................................................................ 26 a. Cleveland-Akron (Canton), Ohio ............................................................. 26 b. Richmond-Petersburg, Virginia ............................................................... 26 c. Honolulu, Hawaii ..................................................................................... 27 d. Amarillo, Texas........................................................................................ 27 ii. Divestiture Markets .............................................................................................. 27 8. TOP-FOUR COMPLIANCE STATEMENTS – HONOLULU, HI AND AMARILLO, TX ............................................................................................................ -

GRAY TELEVISION, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter) Georgia 58-0285030 (State Or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation Or Organization) (I.R.S

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ Annual report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2017 or ☐ Transition report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 for the transition period from __________ to __________. Commission File Number 1-13796 GRAY TELEVISION, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) Georgia 58-0285030 (State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 4370 Peachtree Road, NE Atlanta, GA 30319 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (404) 504-9828 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Class A Common Stock (no par value) New York Stock Exchange Common Stock (no par value) New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: NONE ________________________________________ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.