Lady Alice Le Strange 1585

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beer Shop Beer Shop

1 3 10 11 13 14 West Norfolk C5 E3 C4 C3 Sandringham House C2 C3 VISIT BRITAIN’S BIGGEST BEER SHOP & What To Do 2016 Plus WINE AND SPIRIT WWAREHOUSEAREHOUSE Sandringham House, the Royal Family’s country retreat, ATTRACTIONS is perhaps the most famous stately home in Norfolk - and certainly one of the most beautiful. The Coffee Shop at Thaxters Garden Centre is PLACES TO VISIT Opens Easter 2016 Set in 60 acres of stunning gardens, with a fascinating renowned locally for its own home-made cakes museum of Royal vehicles and mementos, the principal and scones baked daily. Its menu ranges from the EVENTS ground floor apartments with their charming collections popular cooked breakfast to sandwiches, baguettes YOUYOU DON’TDON’T HAVEHAVE Visit King’s Lynn’s of porcelain, jade, furniture and family portraits are open throughout West Norfolk and our homemade specials of the day. During the stunning new to the public. Visitor Centre open every day all year. warmer months there is an attractive garden when TOTO TRAVELTRAVEL THETHE attraction, which Open daily 26 March- 30 October you can sit and enjoy lunch and coffee. EXCEPT Wednesday 27 July. tells the stories of the Take a stroll around the attractive Garden Centre. Adults £14.00, Seniors £12.50, Children £7.00 GLOBEGLOBE TOTO ENJOYENJOY seafarers, explorers, Family (2 adults + 3 children) £35.00 It sells everything the garden could need as well as merchants, mayors, www.sandringhamestate.co.uk a large range of giftware. WORLDWORLD BEERS.BEERS.BEERS. magistrates and If you are staying in self-catering accommodation 4 North Brink, Wisbech, PE13 1LW 12 or a caravan there is a well stocked grocery store Tel: 01945 583160 miscreants who have A5 www.elgoods-brewery.co.uk C4 on site that sells hot chickens from its rotisserie, It is just a short haul to shaped King’s Lynn, one of freshly baked bread, newspapers, lottery and England’s most important everything you could possibly need. -

Norfolk Through a Lens

NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service 2 NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service History and Background The systematic collecting of photographs of Norfolk really began in 1913 when the Norfolk Photographic Survey was formed, although there are many images in the collection which date from shortly after the invention of photography (during the 1840s) and a great deal which are late Victorian. In less than one year over a thousand photographs were deposited in Norwich Library and by the mid- 1990s the collection had expanded to 30,000 prints and a similar number of negatives. The devastating Norwich library fire of 1994 destroyed around 15,000 Norwich prints, some of which were early images. Fortunately, many of the most important images were copied before the fire and those copies have since been purchased and returned to the library holdings. In 1999 a very successful public appeal was launched to replace parts of the lost archive and expand the collection. Today the collection (which was based upon the survey) contains a huge variety of material from amateur and informal work to commercial pictures. This includes newspaper reportage, portraiture, building and landscape surveys, tourism and advertising. There is work by the pioneers of photography in the region; there are collections by talented and dedicated amateurs as well as professional art photographers and early female practitioners such as Olive Edis, Viola Grimes and Edith Flowerdew. More recent images of Norfolk life are now beginning to filter in, such as a village survey of Ashwellthorpe by Richard Tilbrook from 1977, groups of Norwich punks and Norfolk fairs from the 1980s by Paul Harley and re-development images post 1990s. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

Ringstead and Bircham

RINGSTEAD & BIRCHAMRingstead 17 miles / 27.25 km Business open times may vary. Bircham 6.5 miles / 10.5 km Please check withvenue if you look Defibrillator (AED) map location. to use their facilities & services. Village reference (cycling routes). 1 1 Business location (cycling routes). Route. Start point. 2 RINGSTEAD CYCLE ROUTE SEE ‘RURAL RAGS, RURAL RICHES’ Bus Stop Heritage / Point Of Interest Church THORNHAM 1 Drove Orchards 4 Thornham Deli 3 Lifeboat Inn The Orange Tree RINGSTEAD 2 Gin Trap Inn BIRCHAM CYCLE ROUTE The General Store SEE ‘FLOUR POWER’ SEDGEFORD 3 The King William IV Country Inn & Restaurant DOCKING 4 Railway Inn Docking Fish GREAT BIRCHAM 5 Bircham Mill © Crown copyright and database rights 2019 Ordnance Survey 100019340 Bircham Stores and Cafe Kings Head Hotel Peddars Way & Norfolk Coast Path With a pub in each village the Ringstead route passes through, Getting Started it’s the perfect route for leisurely exploration. The shorter This route has two starting points: Bircham route is an ideal route for families; Combined with a Ringstead village green/picnic area (TF705410). visit to the mill, it makes for a great family day out in the Norfolk Bircham Windmill (TF759327). countryside. For those seeking chal-lenge, or faster cyclists that Parking want to visit everything the area has to offer, why not combine For Ringstead starting point there is limited car parking in the the two routes into one loop? village. For Bircham Windmill start point there is on-site car parking West Norfolk has been home to notable politicians, distinguished ladies subject to opening times. -

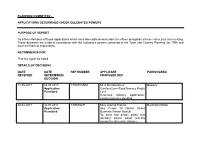

Delegated List

PLANNING COMMITTEE - APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 11.05.2017 04.07.2017 17/00918/RM Mr & Mrs Blackmur Bawsey Application Conifers Lynn Road Bawsey King's Permitted Lynn Reserved Matters Application: construction of a dwelling 24.04.2017 12.07.2017 17/00802/F Miss Joanna Francis Burnham Norton Application Sea Peeps 19 Norton Street Permitted Burnham Norton Norfolk To erect two timber gates and ancillary picket panel fencing across the driveway entrance 12.04.2017 17.07.2017 17/00734/F Mr J Graham Burnham Overy Application The Images Wells Road Burnham Permitted Overy Town King's Lynn Construction of bedroom 22.02.2017 30.06.2017 17/00349/F Mr And Mrs J Smith Brancaster Application Carpenters Cottage Main Road Permitted Brancaster Staithe Norfolk Use of Holiday accommodation building as an unrestricted C3 dwellinghouse, including two storey and single storey extensions to rear and erection of detached outbuilding 05.04.2017 07.07.2017 17/00698/F Mr & Mrs G Anson Brancaster Application Brent Marsh Main Road Permitted Brancaster Staithe King's Lynn Demolition of existing house and -

6 June 2016 Applications Determined Under

PLANNING COMMITTEE - 6 JUNE 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 09.03.2016 29.04.2016 16/00472/F Mr & Mrs M Carter Bagthorpe with Barmer Application Cottontail Lodge 11 Bagthorpe Permitted Road Bircham Newton Norfolk Proposed new detached garage 18.02.2016 10.05.2016 16/00304/F Mr Glen Barham Boughton Application Wits End Church Lane Boughton Permitted King's Lynn Raising existing garage roof to accommodate a bedroom with ensuite and study both with dormer windows 23.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00590/F Mr & Mrs G Coyne Boughton Application Hall Farmhouse The Green Permitted Boughton Norfolk Amendments to extension design along with first floor window openings to rear. 11.03.2016 05.05.2016 16/00503/F Mr Scarlett Burnham Market Application Ulph Lodge 15 Ulph Place Permitted Burnham Market Norfolk Conversion of roofspace to create bedroom and showerroom 16.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00505/F Holkham Estate Burnham Thorpe Application Agricultural Barn At Whitehall Permitted Farm Walsingham Road Burnham Thorpe Norfolk Proposed conversion of the existing barn to residential use and the modification of an existing structure to provide an outbuilding for parking and storage 04.03.2016 11.05.2016 16/00411/F Mr A Gathercole Clenchwarton Application Holly Lodge 66 Ferry Road Permitted Clenchwarton King's Lynn Proposed replacement sunlounge to existing dwelling. -

Magical Weddings at Heacham Manor

Magical Weddings at Heacham Manor HEACHAM MANOR 2018 WEDDING BROCHURE 220 x 305 AW for website.indd 1 11/01/2019 14:32 2 HEACHAM MANOR 2018 WEDDING BROCHURE 220 x 305 AW for website.indd 2 11/01/2019 14:32 Congratulations on your engagement and thank you for considering Heacham WelcomeManor for your special day. Heacham Manor is unique, from the beautiful venue, our experienced and friendly team, to the award-winning cuisine, attentive service, value and flexibility we have been delivering since the hotel opened in 2009. We want this to be the wedding you have always dreamed of. This is possible with the personal assistance of our experienced and dedicated Wedding Coordinator who knows the venue inside out and will be your trusted companion from start to finish. We look forward to making your dream wedding come true. www.heacham-manor.co.uk 3 HEACHAM MANOR 2018 WEDDING BROCHURE 220 x 305 AW for website.indd 3 11/01/2019 14:32 An Exclusive Venue You will have exclusive use of the Manor House, a historic Grade II listed country house set in picturesque gardens, close to the charming Victorian seaside town of Hunstanton and the beautiful beaches of the North Norfolk coast. A perfect venue for a truly romantic wedding. Heacham Manor is unique in the North West Norfolk area, in that it can easily cater for 100+ guests for the ceremony, reception and bedroom accommodation. It also boasts a boutique Spa, 18-hole golf course and an AA Rosette Restaurant. www.heacham-manor.co.uk 4 HEACHAM MANOR 2018 WEDDING BROCHURE 220 x 305 AW for website.indd 4 11/01/2019 14:32 The Bedrooms Heacham Manor’s 45 bedrooms range from the 13 luxurious Manor House Rooms, including the newly refurbished* Manor Suite (the “Bridal Suite”), to the 32 adjacent Norfolk-style Cottage Rooms and Suites that cater magnificently for couples and families. -

NORFOLK. SMI 793 Dyball Alfred, West Raynham, Faken- Hales William Geo

TRADES DIRECTORY. J NORFOLK. SMI 793 Dyball Alfred, West Raynham, Faken- Hales William Geo. Ingham, Norwich Kitteringham John, Tilney St. Law- ham Hall P. Itteringham, Aylsham R.S.O rence, Lynn Dyball E. T. 24 Fuller's hill, Yarmouth Hammond F. Barroway Drove, Downhm Knights Edwd. H. London rd. Harleston Dye Henry Samuel, 39 Audley street & Hammond Richard, West Bilney, Lynn Knott Charles, Ten Mile Bank, Downhm North Market road, Yarmouth & at Pentney, Swaffham Kybird J ames, Croxton, Thetford Earl Uriah, Coltishall, Norwich Hammond Robert Edward Hazel, Lade Frederick Wacton, Long Stratton Easter Frederick, Mileham, Swaffham Gayton, Lynn Lake Thomas, Binham, Wighton R.S.O Easter George, Blofield, Norwich Hammond William, Stow Bridge, Stow Lambert William Claydon, Wiggenhall Ebbs William, Alburgh, Harleston Bardolph, Downham St. Mary Magdalen, Lynn Edward Alfred, Griston, Thetford Hanton J ames, W estEnd street, Norwich Langham Alfred, Martham, Yarmouth Edwards Edward, Wretham, Great Harbord P. Burgh St. Margaret, Yarmth Lansdell Brothers, Hempnall, Norwich Hockham, Thetford Hardy Harry, Lake's end, Wisbech Lansdell Albert, Stratton St. Mary, Eggleton W. Great Ryburgh, Fakenham Harper Robt. Alfd. Halvergate, Nrwch Long Stratton R.S.O Eglington & Gooch, Hackford, Norwich Harrold Samuel, Church end, West Larner Henry, Stoke Ferry ~.0 Eke Everett, Mulbarton, Norwich Walton, Wisbech Last F. B. 93 Sth. Market rd. Yarmouth Eke Everet, Bracon Ash, Norwich Harrowven Henry, Catton, Norwich Lawes Harry Wm. Cawshm, Norwich Eke James, Saham Ton.ey, Thetford Hawes A. Terrington St. John, Wisbech Laws .Jo~eph, Spixworth, Norwich Eke R. Drayton, Norwich Hawes Robert Hilton, Terrington St. Leader James, Po!'ltwick, Norwich Ellis Charles, Palling, Norwich Clement, Lynn Leak T. -

NORFOLK. Bould : the Lectern

128 DOCKING. NORFOLK. bould : the lectern,. of carved oak, was presented m Strachan Charles Edward E*lq. Heacham hall, Lynn n'l82 by the Misse:i! Chadwick, of Tunbridge Wells, in The chairmen of the New Hunstanton Urban District. memory of Mrs. H. E. Ha.re: the ancient font 'i.IJ adorned Council & Docking ,Rural District Council, for the with many carved figures, but much mutilated: the time being, are ex-oili.cio justices of the peace ohurch was new roofed in r875, and additions made, Clerk to the Justic~ G. Whitby, Hunstanton at a. cost of over £4,ooo, and now affords 65o sit tings. The register dates from tihe year 155 8. The Petty Se8sions are helq at the Sessions house, Docking, living is a. discharged vicarage, gross yearly . value the last monday in every month at r r a. m. & at the Council hall, New Hnnstanton, on t·he second monday £419, with 45 acres of glebe and residence, in the gift in each month at 10.30 a.m. The following places are of the Provost and Fellows of Eton College, on the included in the petty sessional division :-Barwick, nomination of the Bishop of Norwich, and held since Bircham Great, Birobam Newton, Biraham Tofts, Bran 1909 by the Rev. James Amiraux Fletcher B.A. of caster, Bul"'ltbam Deepdale, Burnb!lm Norton, Burnbam Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, surrogate· and Sutton & Uiph, Burnham Overy, Burnham Westgate; chaplain of. Docking union. The great tithes are .Buruham• Thorpe, North & South Creake, Ohoseley, commuted at [1,II4. The Wesleyan chapel is of red Docking, Fring, Heaoh:1m, Holme-next-the-Sea., Hun brick, and was erected in 1821 ; the Primitive Methodist stanton, New Hunsta'lton, Ingoldisthorpe, Ringstead, chapel, also of brick faced with cement, was erected in Sedgeford, .Shernbonrne, Snettisham, Stanhoe, Thorn 1836, and has 350 sittings. -

SITUATION of POLLING STATIONS Parliamentary North West Norfolk

SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Parliamentary North West Norfolk Constituency Date of Election: Thursday 12 December 2019 Hours of Poll: 7:00 am to 10:00 pm Notice is hereby given that: The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Ranges of electoral register Ranges of electoral register Station Station Situation of Polling Station numbers of persons entitled Situation of Polling Station numbers of persons entitled Number Number to vote thereat to vote thereat Minster Court, Fairstead, KING'S LYNN 83 PA1-1 to PA1-1501/1 Minster Court, Fairstead, KING'S LYNN 83 PD2-1 to PD2-89 King's Lynn Bowls Club, Beulah Street, King's Lynn Bowls Club, Beulah Street, 84 PA2-1 to PA2-596 84 PB2-1/1 to PB2-569 Gaywood Gaywood The Church of Jesus Christ, Latter Day Saints, St. Raphael Club, Parkway, KING'S LYNN 85 PB1-2 to PB1-1701 86 PC1-1 to PC1-1824 Reffley Lane, KING'S LYNN The Church of Jesus Christ, Latter Day Saints, The Church of Jesus Christ, Latter Day Saints, 87 PC1-1824/1 to PC1-3648/1 87 PC3-1 to PC3-137 Reffley Lane, KING'S LYNN Reffley Lane, KING'S LYNN King's Lynn Masonic Centre, Hamburg Way, King's Lynn Masonic Centre, Hamburg Way, 88 PC2-1 to PC2-1438 89 PC2-1439 to PC2-2748/2 KING'S LYNN KING'S LYNN Fairstead Community Centre, Centre Point, Fairstead Community Centre, Centre Point, 90 PD1-1 to PD1-2257/1 91 PD1-2264 to PD1-4427 KING'S LYNN KING'S LYNN Discovery Youth Centre, Columbia Way, Discovery Youth Centre, Columbia Way, 92 PE1-1 to PE1-2021 93 PF1-1 to PF1-2202 KING'S LYNN KING'S LYNN South Lynn Community Centre, 10 St. -

Listed Buildings and Scheduled Ancient Monuments in King’S Lynn and West Norfolk

Listed Buildings and Scheduled Ancient Monuments In King’s Lynn and West Norfolk with IDox References 10th Edition March 2020 2 LISTED BUILDINGS Property Designation IDox Ref No ANMER St Mary’s Church II* 763 ASHWICKEN Church Lane All Saints Church II* 1248 War Memorial II 1946 BABINGLEY Ruins of Church of St Felix I & SAM 1430 BAGTHORPE WITH BARMER Bagthorpe St Mary’s Church II 764 1 – 4 Church Row II 765 (Listed as 9 and 10 cottages 25m S of Church) II 766 Hall Farmhouse II 767 K6 Telephone kiosk NW of Church II 770 Barmer Barn 50m N of Barmer Farmhouse II 768 All Saints Church II* 769 BARTON BENDISH Barton Hall II 771 Dog Kennels 20m N Barton Hall II 772 St Mary’s Church I 773 Church Road St Andrew’s Church I 774 Barton Bendish War Memorial II 1948 26 (Listed as Old Post Office) II 775 27 (Listed as cottage adjacent to Old Post Office) II 776 Avenue House II 777 Buttlands Lane K6 Telephone kiosk II 778 BARWICK Great Barwick Barwick Hall II 779 Stable block 10m S Barwick Hall II 780 Little Barwick Barwick House II 781 Stable block 10m NE Barwick House II 782 Carriage block 50m NE Barwick House II 783 BAWSEY Ruined church of St James I & SAM 784 Church Farmhouse II 785 Mintlyn Ruined church of St Michael II* 786 Font against S side Whitehouse Farmhouse II 787 (farmhouse not listed) 3 BEXWELL Barn north of St Mary’s Church II & SAM 1421 Church of St Mary The Virgin II* 1422 Bexwell Hall Farmhouse II 1429 War Memorial A10 Bexwell/Ryston II 1908 BIRCHAM Bircham Newton All Saints Church II* 788 The Old House II 789 Bircham Tofts Ruined Church -

295 Le Strange V Creamer and Stileman

1 372 LE STRANGE V CREAMER AND STILEMAN Sir Hamon Le Strange of Hunstanton, co. Norfolk, knt v Robert Creamer of Little Massingham and Robert Stileman of Snettisham, co. Norfolk, gents Michaelmas term, 1638 – June 1640 Name index: Armiger, John, gent Bacon, Robert, mercer Banyard, Edmund, husbandman Bell, Mary Bell, Robert Blackhead, John, scrivener Bramston, John, knight (also Branston) Burnham, Thomas, yeoman Chosell, Thomas, husbandman Clarke, Dr Claxton, Hamon, clerk Clowdeslie, Thomas, gent Cobbe, Edmund, gent (also Cobb) Cobbe, George (also Cobb) Cobbe, Martin, gent (also Cobb) Crampe, Thomas, yeoman Creamer, Bridget (also Cremer) Creamer, Edmund (also Cremer) Creamer, Robert, gent (also Cremer) Crooke, George, knight (also Croke, Crook) Dawney, Thomas, clerk Dixe, Thomas, gent (also Dix) Duck, Arthur, lawyer Eden, Thomas, lawyer Eldgar, John the elder Eldgar, John the younger Garey, Nathaniel, notary public Goldsmith, Robert, miller Gooding, Mr Goodwin, Vincent, clerk Gournay, Edward, esq (also Gurney) Hendry, Thomas Houghton, Robert, esq Hovell, Hugh, gent Hoverson, Roger Howard, Henry, baron Maltravers Howard, Thomas, earl of Arundel and Surrey Jenner, Edmund, yeoman (also Jeynor) Le Strange, Alice, lady (also L’Estrange) Le Strange, Hamon, knight (also L’Estrange) Le Strange, Mary, lady (also L’Estrange) Le Strange, Nicholas, baronet (also L’Estrange) Le Strange, Nicholas, knight (also L’Estrange) 2 Lewin, William, lawyer Lewkenor, Alice Lewkenor, Edward, knight Lownde, Ralph Mileham, Edward, esq Mordaunt, Henry, esq Neve, William,