World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation Lead Authors:∗ Tamara Gurevich and Peter Herman Contributing Authors: Nabil Abbyad, Meryem Demirkaya, Austin Drenski, Jeffrey Horowitz, and Grace Kenneally Version 1.00 Abstract This document provides technical documentation for the Dynamic Gravity dataset. The Dynamic Gravity dataset provides extensive country and country pair information for a total of 285 countries and territories, annually, between the years 1948 to 2016. This documentation extensively describes the methodology used for the creation of each variable and the information sources they are based on. Additionally, it provides a large collection of summary statistics to aid in the understanding of the resulting Dynamic Gravity dataset. This documentation is the result of ongoing professional research of USITC Staff and is solely meant to represent the opinions and professional research of individual authors. It is not meant to represent in any way the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission or any of its individual Commissioners. It is circulated to promote the active exchange of ideas between USITC Staff and recognized experts outside the USITC, professional devel- opment of Office Staff and increase data transparency by encouraging outside professional critique of staff research. Please address all correspondence to [email protected] or [email protected]. ∗We thank Renato Barreda, Fernando Gracia, Nuhami Mandefro, and Richard Nugent for research assistance in completion of this project. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Nomenclature . .3 1.2 Variables Included in the Dataset . .3 1.3 Contents of the Documentation . .6 2 Country or Territory and Year Identifiers 6 2.1 Record Identifiers . -

Sustained Prehistoric Exploitation of a Marshall Islands Fishery

Sustained prehistoric exploitation of a Marshall Islands fishery: ichthyoarchaeological approaches, marine resource use, and human- environment interactions on Ebon Atoll Ariana Blaney Joan Lambrides BA (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2017 School of Social Science Abstract Atolls are often characterised in terms of the environmental constraints and challenges these landscapes impose on sustained habitation, including: nutrient-poor soils and salt laden winds that impede plant growth, lack of perennial surface fresh water, limited terrestrial biodiversity, and vulnerability to extreme weather events and inundation since most atolls are only 2-3 m above sea level. Yet, on Ebon Atoll, Republic of the Marshall Islands in eastern Micronesia, the oceanside and lagoonside intertidal marine environments are expansive, with the reef area four times larger than the land area, supporting a diverse range of taxa. Given the importance of finfish resources in the Pacific, and specifically Ebon, this provided an ideal context for evaluating methods and methodological approaches for conducting Pacific ichthyoarchaeological analyses, and based on this assessment, implement high resolution and globally recognised approaches to investigate the spatial and temporal variation in the Ebon marine fishery. Variability in landscape use, alterations in the range of taxa captured, archaeological proxies of past climate stability, and the comparability of archaeological and ecological datasets were considered. Utilising a historical ecology approach, this thesis provides an analysis of the exploitation of the Ebon marine fishery from initial settlement to the historic period—two millennia of continuous occupation. The thesis demonstrated the importance of implementing high resolution methods and methodologies when considering long-term human interactions with marine fisheries. -

Aviation in the Pacific International Aviation Services Are Crucial to Trade, Growth, and Development in the Pacific Region

Pacific Studies Series About Oceanic Voyages: Aviation in the Pacific International aviation services are crucial to trade, growth, and development in the Pacific region. Improved access provided by international aviation from every other region in the world to an increasing number of islands is opening new opportunities. Tourism contributes substantially to income and employment in many Pacific countries, usually in areas outside of the main urban centers, and enables air freight services for valuable but perishable commodities that would otherwise not be marketable. Although some features of the Pacific region make provision of international aviation services a challenge, there have also been some notable successes that offer key lessons for future development. Case studies of national aviation sector experience show the value of operating on commercial principles, attracting international and OCEANIC V private-sector capital investment, assigning risk where it can best be managed, and liberalizing market access. Integration of the regional market for transport services, combined with harmonized but less restrictive regulations, would facilitate a greater range of services at more competitive prices. Pacific island country governments have the ability to create effective operating environments. When they do so, experience O shows that operators will respond with efficient service provision. YAGES: About the Asian Development Bank Av ADB aims to improve the welfare of the people in the Asia and Pacific region, IATI particularly the nearly 1.9 billion who live on less than $2 a day. Despite many success stories, the region remains home to two thirds of the world’s poor. ADB is O N IN THE PACIFIC a multilateral development finance institution owned by 67 members, 48 from the region and 19 from other parts of the globe. -

Marshall Islands

Country Guide to Gamefishing in the Western and Central Pacific by Wade Whitelaw Oceanic Fisheries Programme Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2001 © Copyright Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2001 All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. The SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this mate- rial for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided the SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the docu- ment and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. Original text: English Secretariat of the Pacific Community Cataloguing-in-publication data Whitelaw, Wade Country guide to gamefishing in the Western and Central Pacific: by Wade Whitelaw 1. Fishing - Oceania. 1. Title 2. Secretariat of the Pacific Community 799.1665 AACR2 ISBN 982–203–817–8 Secretariat of the Pacific Community BP D5 98848 Noumea Cedex New Caledonia Telephone: + 687 26 20 00 Facsimile: + 687 26 38 18 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.spc.int/ Funded by AusAID Layout: Muriel Borderie Prepared for publication and printed at Secretariat of the Pacific Community headquarters Noumea, New Caledonia, 2001 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . .1 BACKGROUND . .2 SOURCES OF INFORMATION . .4 RESULTS . .4 WORLD RECORDS . .5 SEASONALITY OF GAMEFISH SPECIES . .5 SEASONALITY OF TOURISM . .5 SUMMARY OF INFORMATION BY COUNTRY . .6 American Samoa . .7 Cook Islands . .11 Federated States of Micronesia . .15 Fiji Islands . .19 French Polynesia . .23 Guam . .27 Kiribati . .31 Marshall Islands . -

SOLOMON AIRLINES We’Re Redefining Airline Growth

ISSUE APRIL 2015 7 ISSN 2304-5043 PACIFICAVIATION MAGAZINE THE PACIFIC'S LEADING AVIATION MAGAZINE | No.1 in Circulation and Readershipskies FEATURE AIRLINE: SOLOMON AIRLINES We’re redefining airline growth Maximize the revenue from every seat sold Travelport’s Merchandising Platform transforms the way you deliver, differentiate and retail your brand to over 67,000 travel agency customers globally. Our award-winning and industry-leading technology, encompassing Rich Content and Branding, Aggregated Shopping and Ancillary Services, is designed to maximize the revenue you can generate from every seat sold. Discover how our platform can help grow your business. Please contact [email protected] for more information. © 2014 Travelport. All rights reserved travelport.com ISSUE APRIL 2015 7 ISSN 2304-5043 PACIFICAVIATION MAGAZINE skies FRONT COVER: Solomon Airlines See cover story for more information 13 20 40 56 Contents 04 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVES 41 SUNFLOWER AVIATION LIMITED Message from Director SPC Economic 43 PACIFIC FLYING SCHOOL Development Division Message from Secretary-General Association of 46 PACIFIC AVIATION SAFETY OFFICE South Pacific Airlines PASO climbing to greater heights 06 ASSOCIATION OF SOUTH PACIFIC 47 PACIFIC AVIATION SECURITY AIRLINES Pacific Island aviation security capacity building Regional meeting of aviation experts at the 61st ASPA 49 TRANSPORTATION SECURITY General Session ADMINISTRATION 12 CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY OF NEW Aviation security: The importance of building CALEDONIA unpredictability and -

ISSUE 71 Be the Captain of Your Own Ship

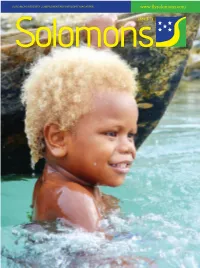

SOLOMON AIRLINE’S COMPLIMENTARY INFLIGHT MAGAZINE www.flysolomons.com SolomonsISSUE 71 be the captain of your own ship You are in good hands with AVIS To make a reservation, please contact: Ela Motors Honiara, Prince Philip Highway Ranadi, Honiara Phone: (677) 24180 or (677) 30314 Fax: (677) 30750 Email:[email protected] Web: www.avis.com Monday to Friday 8:00am to 5:00pm - Saturday – 8:00am to 12:00pm - Sunday – 8.00am to 12:00pm Solomons www.flysolomons.com WELKAM FRENS T o a l l o u r v a l u e d c u s t o m e r s Mifala hapi tumas fo wishim evriwan, Meri Xmas and Prosperous and Safe New Year Ron Sumsum Chief Executive Officer Partnerships WELKAM ABOARD - QANTAS; -our new codeshare partnership commenced Best reading ahead on the 15th November 2015. Includes the following- This is a major milestone for both carriers considering our history together now re-engaged. • Cultural Identity > the need to foster our cultures Together, Qantas and Solomon Airlines will service Australia with four (4) weekly services to and from Brisbane and one (1) service to Sydney • Love is in the Air > a great wedding story on the beautiful Papatura with the best connections within Australia and Trans-Tasman and Resort in Santa Isabel Domestically within Australia as well as Worldwide. This is a mega partnership from our small and friendly Hapi Isles. • The Lagoon Festival > the one Festival that should not be missed Furthermore, we expect to commence a renewed partnership with our annually Melanesian brothers in Air Vanuatu with whom we plan to commence our codeshare from Honiara to Port Vila and return each Saturday and • The Three Sisters Islands of Makira > with the Crocodile Whisperers Sunday each week. -

ATOLL RESEARCH Bulletln

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETlN NO. 235 Issued by E SMTPISONIAIV INSTITUTION Washington, D.C., U.S.A. November 1979 CONTENTS Abstract Introduction Environment and Natural History Situation and Climate People Soils and Vegetation Invertebrate Animals Vertebrate Animals Material and Methods Systematics of the Land Crabs Coenobitidae Coenobi ta Coenobi ta brevimana Coenobi ta per1 a ta Coenobi ta rugosa Birgus Birgus latro Grapsidae Geogxapsus Geograpsus crinipes Geograpsus grayi Metopograpsus Metopograpsus thukuhar Sesarma Sesarma (Labuaniurn) ?gardineri ii Gecarcinidae page 23 Cardisoma 2 4 Cardisoma carnif ex 2 5 Cardisoma rotundum 2 7 Tokelau Names for Land Crabs 30 Notes on the Ecology of the Land Crabs 37 Summary 4 3 Acknowledgements 44 Literature Cited 4 5 iii LIST OF FIGURES (following page 53) 1. Map of Atafu Atoll, based on N.Z. Lands and Survey Department Aerial Plan No. 1036/7~(1974) . 2. Map of Nukunonu Atoll, based on N.Z. Lands and Survey Department Aerial Plan No. 1036/7~sheets 1 and 2 (1974). 3. Map of Fakaofo Atoll, based on N.Z. Lands and Survey Department Aerial Plan No. 1036/7C (1974). 4. Sesarma (Labuanium) ?gardineri. Dorsal view of male, carapace length 28 rnm from Nautua, Atafu. (Photo T.R. Ulyatt, National Museum of N. Z.) 5. Cardisoma carnifex. Dorsal view of female, carapace length 64 mm from Atafu. (Photo T.R. Ulyatt) 6. Cardisoma rotundurn. Dorsal view of male, carapace length 41.5 mm from Village Motu, Nukunonu. (Photo T.R. Ulyatt) LIST OF TABLES 0 I. Surface temperature in the Tokelau Islands ( C) Page 5 11. Mean rainfall in the Tokelau Islands (mm) 6 111, Comparative list of crab names from the Tokelau Islands, Samoa, Niue and the Cook islands, 3 5 IV. -

Hold Fast to the Treasures of Tokelau; Navigating Tokelauan Agency in the Homeland and Diaspora

1 Ke Mau Ki Pale O Tokelau: Hold Fast To The Treasures of Tokelau; Navigating Tokelauan Agency In The Homeland And Diaspora A PORTFOLIO SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES AUGUST 2014 BY Lesley Kehaunani Iaukea PORTFOLIO COMMITTEE: Terence Wesley-Smith, Chairperson David Hanlon John Rosa 2 © 2014 Lesley Kehaunani Iaukea 3 We certify that we have read this portfolio and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a portfolio for the degree of Master of Arts in Pacific Islands Studies. _____________________________ Terence Wesley-Smith Chairperson ______________________________ David Hanlon ______________________________ John Rosa 4 Table of Contents Table of Contents 4 Acknowledgements 6 Chapter One: Introduction 8 1. Introduction 8 2. Positionality 11 3. Theoretical Framework 13 4. Significance 14 5. Chapter outline 15 Chapter Two: Understanding Tokelau and Her People 18 1. Tokelau and her Atolls 20 2. Story of Creation from abstract elements 21 3. Na Aho O Te Pohiha (The days of darkness) 21 4. Peopling of the Tokelau Atolls 23 5. Path of Origin 24 6. Fakaofo 25 7. Nukunonu 26 8. Atafu 26 9. Olohega 26 10. Olohega meets another fate 27 11. Western contact 30 12. Myth as Practice 31 Chapter Three: Cultural Sustainability Through an Educational Platform 33 1. Education in Tokelau 34 2. The Various Methods Used 37 3. Results and impacts achieved from this study 38 4. Learning from this experience 38 5. Moving forward 43 6. -

Håfa Adai Everyday

SharingHåfa the Håfa AdaiAdai Spirit with EverydayOur Visitors and Each Other February 2016, Volume 4, Issue No. 12 HÅFA ADAI PLEDGE CEREMONY LIVING THE HÅFA ADAI PLEDGE Service with Håfa Adai is our business Guahan Insurance’s team from left: Brent Butler, Yuka Oguma, Shyla Santiago, Erica Gumataotao, Lorna Malbog, Dee Camacho, Naidene Rios and Kyoko Nakanishi. A HÅFA ADAI PLEDGE CEREMONY WAS HELD JANUARY 26 AT TERRY’S LOCAL COMFORT FOOD IN TUMON. From left: Edrienne Hernandez, family Guahan Insurance Services, Inc.’s (GIS) main focus and approach every day is member, Terry's Local Comfort Food; Kotwal Singh, owner, Singh's Cafe - to provide the highest level of service. It is important that we emphasize the Kabab Curry; Anthony J.G. Tornito, sole proprietor, Minahgong; Shalyn Allen, Håfa Adai Spirit as we welcome our customers and make them feel right at principal broker, Welcome Home Realty; Nadja Rillamas, realtor, Welcome home. Our licensed insurance associates will help individuals, families and Home Realty; Allison Sollenberg, realtor, Welcome Home Realty and Bianca businesses with customizable coverage that fits their needs and oer savings Cloud, realtor, Welcome Home Realty, proudly display their newly signed Håfa on combined packages. Adai Pledge certificates. Insurance transactions are unique and unlike any other line of business, because the product you purchase is an intangible item. Unlike trying on KAO UN TUNGO’? (Did you know?) clothes or test-driving a vehicle, insurance is dicult to sample. It is important that we eectively communicate and build customer confidence during this Agad’na: Canoe Builders transaction. Our insurance associates can help you map out the best coverage and thoroughly explain the sometimes intricate policy wordings. -

Unlocking the Secrets of Swains Island: a Maritime Heritage Resources Survey

“Unlocking the Secrets of Swains Island:” a Maritime Heritage Resources Survey September 2013 Hans K. Van Tilburg, David J. Herdrich, Rhonda Suka, Matthew Lawrence, Christopher Filimoehala, Stephanie Gandulla National Marine Sanctuaries National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Maritime Heritage Program Series: Number 6 The Maritime Heritage Program works cooperatively and in collaboration within the Sanctuary System and with partners outside of NOAA. We work to better understand, assess and protect America’s maritime heritage and to share what we learn with the public as well as other scholars and resource managers. This is the first volume in a series of technical reports that document the work of the Maritime Heritage Program within and outside of the National Marine Sanctuaries. These reports will examine the maritime cultural landscape of America in all of its aspects, from overviews, historical studies, excavation and survey reports to genealogical studies. No. 1: The Search for Planter: The Ship That Escaped Charleston and Carried Robert Smalls to Destiny. No. 2: Archaeological Excavation of the Forepeak of the Civil War Blockade Runner Mary Celestia, Southampton, Bermuda No. 3: Maritime Cultural Landscape Overview: The Redwood Coast No. 4: Maritime Cultural Landscape Overview: The Outer Banks No. 5: Survey and Assessment of the U.S. Coast Survey Steamship Robert J. Walker, Atlantic City, New Jersey. These reports will be available online as downloadable PDFs and in some cases will also be printed and bound. Additional titles will become available as work on the series progresses. Cover Image - Figure 1: Swains Island satellite image: Image Science & Analysis Laboratory, NASA Johnson Space Center. -

Fields Listed in Part I. Group (8)

Chile Group (1) All fields listed in part I. Group (2) 28. Recognized Medical Specializations (including, but not limited to: Anesthesiology, AUdiology, Cardiography, Cardiology, Dermatology, Embryology, Epidemiology, Forensic Medicine, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Immunology, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oncology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Pediatrics, Pharmacology and Pharmaceutics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiology, Plastic Surgery, Preventive Medicine, Proctology, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, Speech Pathology, Sports Medicine, Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Toxicology, Urology and Virology) 2C. Veterinary Medicine 2D. Emergency Medicine 2E. Nuclear Medicine 2F. Geriatrics 2G. Nursing (including, but not limited to registered nurses, practical nurses, physician's receptionists and medical records clerks) 21. Dentistry 2M. Medical Cybernetics 2N. All Therapies, Prosthetics and Healing (except Medicine, Osteopathy or Osteopathic Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Chiropractic and Optometry) 20. Medical Statistics and Documentation 2P. Cancer Research 20. Medical Photography 2R. Environmental Health Group (3) All fields listed in part I. Group (4) All fields listed in part I. Group (5) All fields listed in part I. Group (6) 6A. Sociology (except Economics and including Criminology) 68. Psychology (including, but not limited to Child Psychology, Psychometrics and Psychobiology) 6C. History (including Art History) 60. Philosophy (including Humanities) -

Inflightmagazine Issue80.Pdf

Globe Pass To over 190 countries. $200 for 90mins Valid for 14days. Dial*888# to subscribe. The future is exciting. Ready? www.flysolomons.com Welkam Frens grading roads and some airport facilities in the Solomon Islands. This funding complements the commitment by JICA to upgrade Honiara Airport. All of which will have a significant impact on tourism in the Solomon Islands. Mr Brett Gebers The worldwide problem with litter seems to be am- plified in Honiara and we are working with a number of parties to find a way of addressing the issue. Unfortunately, It took an awful lot longer than anticipated but we many of the Honiara residents feel that it is normal to are now flying from Brisbane to Munda and returning via throw litter out of the car and bus windows. There are no Honiara on Saturdays. This non-stop service will make it penalties to dumping litter in the gutters and on the roads. easier and cheaper for visitors to get to Munda and the sur- Failure to curb the use of plastic and other non-biodegrad- rounding islands situated in the amazing Marovo Lagoon. able packaging materials will ruin the pristine waters of the Our Twin Otter fleet provides easy connections between Solomon Islands. Munda, Seghe, Gizo and Suavanao. There are also regular During a recent snorkelling visit to the Munda area, I boat services to a number of local destinations. The Marovo was thrilled to see Belinda Botha’s obsession with keeping Lagoon is the longest saltwater lagoon in the world and is the environment pristine being translated into action.