ERSS Focuses on L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Koyna Dam (Pic:Mh09vh0100)

DAM REHABILITATION AND IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (DRIP) Phase II (Funded by World Bank) KOYNA DAM (PIC:MH09VH0100) ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIAL DUE DILIGENCE REPORT August 2020 Office of Chief Engineer Water Resources Department PUNE Region Mumbai, Maharashtra E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Page No. Executive Summary 4 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 PROJECT OVERVIEW 6 1.2 SUB-PROJECT DESCRIPTION – KOYNA DAM 6 1.3 IMPLEMENTATION ARRANGEMENT AND SCHEDULE 11 1.4 PURPOSE OF ESDD 11 1.5 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY OF ESDD 12 CHAPTER 2: INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK AND CAPACITY ASSESSMENT 2.1 POLICY AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK 13 2.2 DESCRIPTION OF INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK 13 CHAPTER 3: ASSESSMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS 3.1 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT 15 3.2 PROTECTED AREA 16 3.3 SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT 18 3.4 CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT 19 CHAPTER 4: ACTIVITY WISE ENVIRONMENT & SOCIAL SCREENING, RISK AND IMPACTS IDENTIFICATION 4.1 SUB-PROJECT SCREENING 20 4.2 STAKEHOLDERS CONSULTATION 24 4.3 DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY OF RISKS AND IMPACTS BASED ON SCREENING 24 CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS 5.1 CONCLUSIONS 26 5.1.1 Risk Classification 26 5.1.2 National Legislation and WB ESS Applicability Screening 26 5.2 RECOMMENDATIONS 27 5.2.1 Mitigation and Management of Risks and Impacts 27 5.2.2 Institutional Management, Monitoring and Reporting 28 List of Tables Table 4.1: Summary of Identified Risks/Impacts in Form SF 3 23 Table 5.1: WB ESF Standards applicable to the sub-project 26 Table 5.2: List of Mitigation Plans with responsibility and timelines 27 List of Figures Figure -

Koyna Hydroelectric Project

IPWI1 WIRiR CiT D- RESTRICTED Report No. TO-325b Public Disclosure Authorized I~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ This report was prepared for use within the Association. It may not be published nor may it be quoted as representing the Association's views. The Association accepts no responsibility for the accurocy or completeness of the contents of the L report,.. INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Public Disclosure Authorized APPRAISAL OF KOYNA HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT STAGE II TNTrTA Public Disclosure Authorized July 30, 1962 Public Disclosure Authorized Djepartment of0 Tech.nical Operations CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS USu,T$1 411d'' J -z.A. '76tIVU ±1LTndi4an Q L"RDupees I Runee or = Zi cents (US) 100 Naya Paisa US $1 Million = Rs. 4, 760, 000 Rs. 1 Million = US $210, 000 TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraphs SUMARY i- ix I. INTRGDUCTION 1 - 5 II. THE BORROWIE 6- 9 The Maharashtra State Electricity Board 7 - 9 III. THE POCMER 1ARKET 10 16 Forecast of Demand and Energy Consumption 13 - 16 IV. THE KOYNA DEVELOPMENT 17 - 21 VI TME PROJECr 22 - 34 Cost of Project 24 - 26 Arrangements for Engineering and Construction 27 - 29 Operation after Completion 30 - 32 Construction Schedule 33 .EXpenditure Schedule 34 VI. FINANCIAL ASPECTS 35 - 8 Tariffs 35 - 37 FinanG-ia1 Plnn 38 -4 Estimated Future Earnings 44 - 45 De o I _ 1.7 -- t- Vw*ss VX L4 I Auditors 48 VII. CONCLUSIONS 49 - 5 A MMT TT__T__-- _ _- -' I = _ * _'m;- aA; _ ;{ | afiI.:r1 ~ fvH.l nyuvut tUt;V±.t -

Gk Power Capsule for Rbi Assistant/ Ippb Mains & Idbi Po

ljdkjh ukSdjh ikuk gS] dqN dj ds fn[kkuk gS! GK POWER CAPSULE FOR RBI ASSISTANT/ IPPB MAINS & IDBI PO Powered by: GK POWER CAPSULE FOR RBI ASSISTANT | IPPB & IDBI PO(MAINS) 2017 MUST DO CURRENT AFFAIRS TOPICS 62nd Filmfare Awards 2017 declared: Aamir Khan & Alia Best Actor in Motion Picture or Musical or Comedy: Ryan Bhatt Bags Top Honour Gosling for La La Land. Best Actress in Motion Picture Musical or Comedy: At the glittering Filmfare awards, "Dangal" swept away three Emma Stone for La La Land. of four major awards -- Best Film, Aamir Khan won Best Actor Best Original Score-Motion Picture: Justin Hurwitz for the and Nitesh Tiwari won Best Director award while Alia La La Land. Bhatt won the Filmfare Best Actor Award (Female) for her Best Original Song: “City of Stars” (Justin Hurwitz, Pasek & performance in "Udta Punjab". Paul) for the La La Land. Best Foreign Language Film: Elle (France). The winners of 62nd Jio Filmfare Awards are following:- Best Choreography : Adil Shaikh - Kar gayi chul (Kapoor & ICC Awards 2016 announced: It was all Kohli there Sons) Ravichandran Ashwin has won both the ICC Cricketer of the Best Editing: Monisha R Baldawa - Neerja Year and the ICC Test cricketer of the Year award after he was Best Lyrics: Amitabh Bhattacharya – Channa mereya (Ae Dil named as the only Indian in ICC’s Test Team of the Year. Virat Hai Mushkil) Kohli was named the captain of the ICC ODI Team of the Best Story: Shakun Batra and Ayesha Devitre - Kapoor & Year. Misbah-Ul-Haq won the ICC Spirit of Cricket Award at Sons the 2016 ICC Awards as he became the first Pakistan player to Best Dialogue: Ritesh Shah - Pink win the award. -

ERSS Was Published in 2012 Under the Name Cirrhinus Fulungee

Deccan White Carp (Gymnostomus fulungee) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, October 2012 Revised, February 2019 Web Version, 5/31/2019 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Froese and Pauly (2019): “Asia: Maharashtra and Karnataka in India; probably in other parts of Indian peninsula.” From Dahanukar (2011): “Cirrhinus fulungee is widely distributed in the Deccan plateau. It is recorded from Krishna and Godavari river system from Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Record of this species from Cauvery river system (Menon 1999) is doubtful. In Maharashtra, the species is known from Mula-Mutha river of Pune (Fraser 1942, Tonapi and Mulherkar 1963, Kharat et al. 2003, Wagh and Ghate 2003), Pashan lake in Pune (Fraser 1942, Tonapi and Mulherkar 1963), Pavana River near Pune (Chandanshive et al. 2007), Ujni Wetland (Yazdani and Singh 1990), Neera river near Bhor (Neelesh Dahanukar, Mandar Paingankar, Rupesh Raut and S.S. Kharat, manuscript submitted), Krishna river near Wai (S.S. Kharat, Mandar Paingankar and Neelesh Dahanukar, manuscript in preparation), Koyna river at Patan (Jadhav et al. 2011), Panchaganga river in Kolhapur (Kalawar and Kelkar 1956), Solapur district 1 (Jadhav and Yadav 2009), Kinwat near Nanded (Hiware 2006) and Adan river (Heda 2009). In Andhra Pradesh, the species is known from Nagarjunasagar (Venkateshwarlu et al. 2006). In Karnataka, the species is reported from Tungabhadra river (Chacko and Kuriyan 1948, David 1956, Shahnawaz and Venkateshwarlu 2009, Shahnawaz et al. 2010), Linganamakki Reservoir on Sharavati River (Shreekantha and Ramachandra 2005), Biligiri Ranganathswamy Temple Wildlife Sanctuary (Devi et al. -

An Innovative Technique As Lake Tapping for Dam Structure: a Case Study

International Journal on Recent and Innovation Trends in Computing and Communication ISSN: 2321-8169 Volume: 4 Issue: 4 498 - 501 ______________________________________________________________________________________________ An Innovative Technique as Lake Tapping for Dam Structure: A Case Study Prof. Aakash Suresh Pawar Prof. Lomesh S. Mahajan Prof. Mahesh N. Patil Department of Civil Engineering Department of Civil Engineering Department of Civil Engineering North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon Maharashtra, India Maharashtra, India Maharashtra, India [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract – From the last three decades water resource management becomes very special issue due to uncertain pattern of rainfall all over globe and mainly its drastically affects in south Asian parts. Hydroelectricity uses the energy of running water, without minimizing its quantity, to generate electricity. Therefore, all hydroelectric developments, of small or huge size, whether run of the river accumulated storage, fit the concept of renewable energy. Hydroelectric power plants reservoirs offer incomparable operational flexibility, since they can fast respond to fluctuations in the demand for electricity. The free to adjustment, flexibility and storage capacity of hydroelectric power plants becomes efficient and considerably economical in supplement the use of irregular sources of renewable energy. The operation of electricity systems depends on rapid and flexible generation sources to meet peak demands, maintain the system voltage levels, and quickly re-establish supply after a blackout. Energy generated by hydroelectric installations can be injected into the electricity system faster than that of any other energy source. So providing ancillary services to the electricity system, thus maintaining the balance of water supply availability and fulfill that demand by using a new technique as an additional arrangement for continuous power generation via lake tapping. -

0022-1945 Page No:1084

Journal of Interdisciplinary Cycle Research ISSN NO: 0022-1945 NOMENCLATURE OF SCHISMATORHYNCHUS NUKTA (SYKES, 1839) (CYPRINIFORMES: CYPRINIDAE). Ramalingam Reguananth1, Paramasivan Sivakumar1* and Muthukumarasamy Arunachalam2 1Research Department of Zoology, Poompuhar College (Autonomous), Melaiyur-609 107, Sirkali, Nagapattinam District, Tamil Nadu, India. 2 Department of Animal Science, School of Biological Sciences, Central University of Kerala, Tejaswini Hills, Periye-671316, Kasaragod District, Kerala, India. 1Corresponding author: *E-mail:[email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT Schismatorhynchus nukta (Sykes, 1839) is redescribed from the specimens collected from Bhadra River, a tributary of Krishna River basin and the subgenus is elevated to the genus level as Nukta. Keywords: Nukta nukta. Bhadra River, tributary of Krishna River basin. INTRODUCTION Sykes described Schismatorhynchus (=Cyprinus) nukta from Indrayani River, Maharashtra, a tributary of the Krishna River system. Day (1875, 1889) described it as "Labeo nukta." from the type locality. Occurrence of this species was reported by many authors from Krishna River and its tributaries Mula-Mutha River (Fraser, 1942), Bhima River (Suter, 1944), Ujni Wetland (Yazdani and Singh, 1990, Surwade and Khillare, 2010), and Neera River at Veer dam (Ghate et al. 2002), Koyna River (Jadhav et al. 2011), Panchaganga River (Kalawar and Kelkar, 1956) and Sangli (Jayaram, 1995). In Karnataka it is known from Bhadra River at Bhadravathi (David, 1956), Thunga River (Chacko and Kuriyan, 1948), Bagalkot (Jayaram, 1995) and Doora Lake (Prasad et al. 2009). In Andhra Pradesh it was recorded from Lingalagattu at Sri Sailam and Manthralayam (Jayaram, 1995). Recently one of the authors (M.A.) collected samples of Schismatorhynchus (Nukta) nukta (Sykes) in the Bhadra River at Bhadravathi. -

Emergency Plan

Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 43253-026 November 2019 India: Karnataka Integrated and Sustainable Water Resources Management Investment Program – Project 2 Vijayanagara Channels Annexure 5–9 Prepared by Project Management Unit, Karnataka Integrated and Sustainable Water Resources Management Investment Program Karnataka Neeravari Nigam Ltd. for the Asian Development Bank. This is an updated version of the draft originally posted in June 2019 available on https://www.adb.org/projects/documents/ind-43253-026-eia-0 This environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Annexure 5 Implementation Plan PROGRAMME CHART FOR CANAL LINING, STRUCTURES & BUILDING WORKS Name Of the project:Modernization of Vijaya Nagara channel and distributaries Nov-18 Dec-18 Jan-19 Feb-19 Mar-19 Apr-19 May-19 Jun-19 Jul-19 Aug-19 Sep-19 Oct-19 Nov-19 Dec-19 Jan-20 Feb-20 Mar-20 Apr-20 May-20 Jun-20 Jul-20 Aug-20 Sep-20 Oct-20 Nov-20 Dec-20 S. No Name of the Channel 121212121212121212121212121212121212121212121212121 2 PACKAGE -

District Survey Report 2020-2021

District Survey Report Satara District DISTRICT MINING OFFICER, SATARA Prepared in compliance with 1. MoEF & CC, G.O.I notification S.O. 141(E) dated 15.1.2016. 2. Sustainable Sand Mining Guidelines 2016. 3. MoEF & CC, G.O.I notification S.O. 3611(E) dated 25.07.2018. 4. Enforcement and Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining 2020. 1 | P a g e Contents Part I: District Survey Report for Sand Mining or River Bed Mining ............................................................. 7 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 7 3. The list of Mining lease in District with location, area, and period of validity ................................... 10 4. Details of Royalty or Revenue received in Last five Years from Sand Scooping Activity ................... 14 5. Details of Production of Sand in last five years ................................................................................... 15 6. Process of Deposition of Sediments in the rivers of the District ........................................................ 15 7. General Profile of the District .............................................................................................................. 25 8. Land utilization pattern in district ........................................................................................................ 27 9. Physiography of the District ................................................................................................................ -

(River/Creek) Station Name Water Body Latitude Longitude NWMP

NWMP STATION DETAILS ( GEMS / MINARS ) SURFACE WATER Station Type Monitoring Sr No Station name Water Body Latitude Longitude NWMP Project code (River/Creek) Frequency Wainganga river at Ashti, Village- Ashti, Taluka- 1 11 River Wainganga River 19°10.643’ 79°47.140 ’ GEMS M Gondpipri, District-Chandrapur. Godavari river at Dhalegaon, Village- Dhalegaon, Taluka- 2 12 River Godavari River 19°13.524’ 76°21.854’ GEMS M Pathari, District- Parbhani. Bhima river at Takli near Karnataka border, Village- 3 28 River Bhima River 17°24.910’ 75°50.766 ’ GEMS M Takali, Taluka- South Solapur, District- Solapur. Krishna river at Krishna bridge, ( Krishna river at NH-4 4 36 River Krishna River 17°17.690’ 74°11.321’ GEMS M bridge ) Village- Karad, Taluka- Karad, District- Satara. Krishna river at Maighat, Village- Gawali gally, Taluka- 5 37 River Krishna River 16°51.710’ 74°33.459 ’ GEMS M Miraj, District- Sangli. Purna river at Dhupeshwar at U/s of Malkapur water 6 1913 River Purna River 21° 00' 77° 13' MINARS M works,Village- Malkapur,Taluka- Akola,District- Akola. Purna river at D/s of confluence of Morna and Purna, at 7 2155 River Andura Village, Village- Andura, Taluka- Balapur, District- Purna river 20°53.200’ 76°51.364’ MINARS M Akola. Pedhi river near road bridge at Dadhi- Pedhi village, 8 2695 River Village- Dadhi- Pedhi, Taluka- Bhatkuli, District- Pedhi river 20° 49.532’ 77° 33.783’ MINARS M Amravati. Morna river at D/s of Railway bridge, Village- Akola, 9 2675 River Morna river 20° 09.016’ 77° 33.622’ MINARS M Taluka- Akola, District- Akola. -

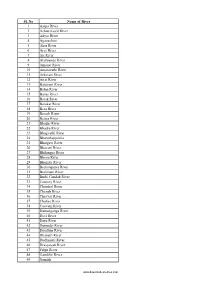

List of Rivers in India

Sl. No Name of River 1 Aarpa River 2 Achan Kovil River 3 Adyar River 4 Aganashini 5 Ahar River 6 Ajay River 7 Aji River 8 Alaknanda River 9 Amanat River 10 Amaravathi River 11 Arkavati River 12 Atrai River 13 Baitarani River 14 Balan River 15 Banas River 16 Barak River 17 Barakar River 18 Beas River 19 Berach River 20 Betwa River 21 Bhadar River 22 Bhadra River 23 Bhagirathi River 24 Bharathappuzha 25 Bhargavi River 26 Bhavani River 27 Bhilangna River 28 Bhima River 29 Bhugdoi River 30 Brahmaputra River 31 Brahmani River 32 Burhi Gandak River 33 Cauvery River 34 Chambal River 35 Chenab River 36 Cheyyar River 37 Chaliya River 38 Coovum River 39 Damanganga River 40 Devi River 41 Daya River 42 Damodar River 43 Doodhna River 44 Dhansiri River 45 Dudhimati River 46 Dravyavati River 47 Falgu River 48 Gambhir River 49 Gandak www.downloadexcelfiles.com 50 Ganges River 51 Ganges River 52 Gayathripuzha 53 Ghaggar River 54 Ghaghara River 55 Ghataprabha 56 Girija River 57 Girna River 58 Godavari River 59 Gomti River 60 Gunjavni River 61 Halali River 62 Hoogli River 63 Hindon River 64 gursuti river 65 IB River 66 Indus River 67 Indravati River 68 Indrayani River 69 Jaldhaka 70 Jhelum River 71 Jayamangali River 72 Jambhira River 73 Kabini River 74 Kadalundi River 75 Kaagini River 76 Kali River- Gujarat 77 Kali River- Karnataka 78 Kali River- Uttarakhand 79 Kali River- Uttar Pradesh 80 Kali Sindh River 81 Kaliasote River 82 Karmanasha 83 Karban River 84 Kallada River 85 Kallayi River 86 Kalpathipuzha 87 Kameng River 88 Kanhan River 89 Kamla River 90 -

New Mahabaleshwar, Satara (Maharashtra) Completion Date: Dec, 2015 Status: Started

https://www.propertywala.com/acreages-mountain-park-satara Acreages Mountain Park - New Mahabaleshwa… Premium Developed Hill Station NA Plots Acreages Presented a Collector Sanctioned, Premium Developed Hill Station NA Plots with ready Infrastructure and Immediate registration. Project ID : J701189980 Builder: Acreages India Properties: Residential Plots / Lands Location: Acreages Mountain Park,Gheradategad Village,Tal- Patan, New Mahabaleshwar, Satara (Maharashtra) Completion Date: Dec, 2015 Status: Started Description Acreages Mountain Park is a Brand New Hill station in Maharashtra Government’s New Mahabaleshwar project. Feel of the same magic of Hill station. It gives a fabulous and undisturbed view for each plot of Konya River, Stunning Valley with widest Wind Mills on hill tops. At 980 MSL (Meters Above sea level) (3215 Feet above sea level), gives you all time icy feeling with 5°C to 28°C Temperature. Salient Features Collector Sanctioned Developed NA Plots Clear title Project Spread across 22 acres Min Plot Area- 2000/2500/3000/3500/4000/5000/6000 sqft upto 18,000 sqft Individual 7×12 FSI for Construction 1:1 Immediate Registration. Plug and Play model. Almost Double the MSL height of Lonavala & Khandala hill Station Undisturbed view for each plot like Mountain, valley and Koyna River with sky touching wind mills Touch to UNESCO World Heritage site Western Ghats with 12 month multi color greenery Maharashtra Govt. Approved Hill Station-New Mahabaleshwar now no further development Allowed in Mahabaleshwar/Panchgani/Matheran Vaastu Obedient Plots Fertile Red Soil Land. 22 tourist destinations within 100 kms including Kas plateau Mobile, Internet and Wi-Fi Accessible Ideal place for Hill station, holiday home and future investment. -

9.2 Landform and Geology

Data Collection Survey on Pumped Storage Hydropower Development in Maharashtra Final Report Lower Reservoir Upper Reservoir Figure 9.1.5-1 Road Map to Kumbhavde Ghat Upper Reservoir and Lower Reservoir 9.2 Landform and Geology Site survey was conducted fot the 3 sites; Panshet, Warasgaon, and Varandh Ghat, and they were compared from physiographical and geological aspects. 9.2.1 Criteria The basic criteria for feasibility assessment of dam construction are described below. Electric Power Development Co., Ltd 9 - 8 Data Collection Survey on Pumped Storage Hydropower Development in Maharashtra Final Report (1) Landform 1) Ability to store and sustain water i) Shape of reservoir: wide valley with a narrowing is ideal ii) Shape of dam axis: thick ridge for an abutment is ideal 2) Vertical distance: Large difference in elevation between the upper and the lower reservoirs (2) Geology 1) Solidity of dam foundation i) Rock type: the harder the better ii) Weathering: the thinner (shallower) the better iii) Deterioration (fault, alteration, etc.): the less the better iv) Heterogeneity (facies change, layer contact, dipping, foliation, etc): the less the better v) Covering layer: the thinner the better Incidentally, as for Warasgaon Alternative (Upper) Reservoir, unlike the others, solidity is not recognized as preferable because the rocks are to be excavated in order to obtain space for water storage. 2) Low Permeability i) Porosity of rock: the less the better ii) Open cracks: the less (and less continuous) the better iii) Ground water level: not necessarily related to permeability, but generally preferred to be near the ground for dams.