Impact of Restricted Marital Practices on Genetic Variation in an Endogamous Gujarati Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Members – List.Pdf

Name Address Pinalbhai Punambhai Patel Near Dairy, Lambhavel, Anand Axit Manubhai Patel Nr. Gayatrimandir, Kasor, Anand Vipul Babubhai Patel Amba Chowk, Boriyavi, Anand Chintan Dipakbhai Patel Dr. Khadki, Samarkha, Anand Hardik Pankajbhai Patel Pipla pol, Lambhavel, Anand Denish Dilipbhai Patel Patel Society, Valasan, Anand Nirmal Maheshbhai Patel Moti Khadki, Vansol, Anand Akash Dipakbhai Patel Piplapol, Lambhavel, Anand Jigar Rajnikant Patel Mahadev Khadki, Lambhavel, Anand Ronak Nikunjbhai Patel Tran Khadki, Valasan, Anand Sagar Bhanubhai Patel Moti Khadki, Petli, Vaso Vishal Ashokbhai Inamdar Inamdar Street, Valasan, Anand Paresh Pujabhai Patel Amba Chowk, Jitodiya, Anand Chandresh Chandubhai Patel Nr. Radha Krushna Mandir Jitodiya, Anand Ramendra Dhanjibhai Patel Valasan, Anand Tarun Ramanbhai Patel Nr. Mota Mahadev, Valasan, Anand Vikas Ganshyambhai Patel Piplavali Khadki, Valasan, Anand Ashok Sankarbhai Patel 11, Tulip Society, Anand Mihir Dilipbhai Patel Near Primary School, Lambhavel, Anand Rakesh Balendrabhai Patel Nr. Swaminarayan Mandir, Piplata Bhavin Vinubhai Patel Jol, Anand Krupesh Nikunjbhai Patel Tran Khadki, Valasan, Anand Mayurbhai Anilbhai Patel 71, Kartavya, Lambhavel, Anand Dipalkumar Vithhalbhai Patel Moti Khadki, Anklav, Anand. Sandipkumar Kanchanbhai Patel Kakanipol, sandesar, Anand Rakeshkumar Anilbhai Patel Nava Ghara, Karamsad, Anand Mukesh Manubhai Patel Swaminarayan Soc, Valasan, Anand Laxmanbhai Ambalalbhai Patel Kakanipol, Sandesar, Anand Shaileshbhai Chimanbhai Patel Motikhadki, Anklav, Anand Dwarkadas -

![Annexure 1 [A] INSTITUTIONAL ETHICS COMMITTEE - 2 H M PATEL CENTRE for MEDICAL CARE and EDUCATION, KARAMSAD, GUJARAT](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1163/annexure-1-a-institutional-ethics-committee-2-h-m-patel-centre-for-medical-care-and-education-karamsad-gujarat-591163.webp)

Annexure 1 [A] INSTITUTIONAL ETHICS COMMITTEE - 2 H M PATEL CENTRE for MEDICAL CARE and EDUCATION, KARAMSAD, GUJARAT

Annexure 1 [a] INSTITUTIONAL ETHICS COMMITTEE - 2 H M PATEL CENTRE FOR MEDICAL CARE AND EDUCATION, KARAMSAD, GUJARAT Member Details [since 1st May, 2018] Sr. Name Qualification with Current Organization Telephone Number, e-mail address Designation/ Affiliation of Member No. specialization Fax Role of member in with Institute that has [02692 – 223660] Ethics Committee constituted the Ethics Committee 1 Dr. Ravindra B Sabnis MS [Surgery] Chairman & Head, +91 9426422002 Chairperson None MCh [Urology] Department of Urology, [email protected] [Clinician] Muljibhai Patel Urological Hospital, Nadiad, Gujarat 2 Dr. Jagdish R Varma MD Associate Professor, +91 9879534750 Deputy Chairperson Employee [Psychiatry] Psychiatry, [email protected] [Clinician] Pramukhswami Medical College, Karamsad 3 Dr. Dinesh Kumar MD Professor, Community +91 9662045484 Member Secretary Employee [Community Medicine, Pramukhswami [email protected] [Public Health Expert] Medicine] Medical College, Karamsad 4 Dr. Viral Patel MD Associate Professor, +91 9825060977 Member Employee [Radiodiagnosis] Department of [Clinician] Radiodiagnosis, SK [email protected] Hospital, Karamsad 5 Mr. Shailesh Panchal MSc Nursing Tutor, Nursing, +91 9879401720 Member Employee [Paediatric] GH Patel Institute of [email protected] [Nursing Faculty] Nursing, Karamsad Page 1 of 3 List of IEC - 2, Members, HMPCMCE Annexure 1 [a] INSTITUTIONAL ETHICS COMMITTEE - 2 H M PATEL CENTRE FOR MEDICAL CARE AND EDUCATION, KARAMSAD, GUJARAT Sr. Name Qualification with Current Organization Telephone Number, e-mail address Designation/ Affiliation of Member No. specialization Fax Role of member in with Institute that has [02692 – 223660] Ethics Committee constituted the Ethics Committee 6 Mr. Nilesh M Panchal LLB, MLW Manager, Personnel and +91 9429254368 Member Employee Administration, Charutar [email protected] [Legal Expert] Arogya Mandal, Karamsad 7 Mr. -

Issar Conf Aau June 2018.Pdf

organizing committee. Acceptance of paper(s) will be : Organizing Committee : communicated to the registered presenting author Patron only through e-mail. Oral presentation will be Dr. N.C. Patel restricted to 7 min, and poster should be of standard Hon'ble Vice-Chancellor, Anand Agricultural University, Anand size, 3'Wx4'L. Only the quality papers will find place Co-Patrons in oral presentation. Prof. V. Chandrasheker Murti, Dr. K.B. Kathiria, ANNOUNCEMENT CUM INVITATION Registration Fee & Mode of Payment: President ISSAR & Professor ARGO Director of Research & Dean XXXIV Annual Convention of the Indian Delegate Category Up to Up to Spot Veterinary College, Bangalore PG Studies, AAU, Anand Society for Study of Animal Reproduction 31.10.208 30.11.2018 Registration Chairman and Members of ISSAR Rs. 4500 Rs. 5000 Rs. 5500 Dr. A.M. Thaker International Symposium on Dean & Principal, College of Vet. Sci. & AH, AAU, Anand Non-member delegates Rs. 5000 Rs. 5500 Rs. 6000 “Productivity Enhancement through Co-Chairmen PG students@ Rs. 2000 Rs. 2000 Rs. 2500 Augmenting Reproductive Efficiency of Dr. Shiv Prasad Dr. M.K. Jhala Livestock for Sustainable Rural Economy” Accompanying person Rs. 2000 Rs. 2500 Rs. 3000 General Secretary, ISSAR & Asso. Director of Research (ASc), Foreign delegate US $150 US $180 US $200 HoD, ARGO, GBPAUT, Pantnagar AAU, Anand 28-30 December, 2018 Retired life members of ISSAR - free registration. Organizing Secretary @ Authentication from Guide/Dean is mandatory. Dr. A.J. Dhami A/C payee/ multicity cheque or DD may be drawn Professor & Head, Dept. of Vety Gynaecology & Obstetrics in favour of “Organizing Secretary, ISSAR President, ISSAR, Gujarat Chapter Symposium-2018” payable at Anand” and sent by name. -

ANAND DISTRICT PASS out TRAINEE DETAILS Sr

ANAND DISTRICT PASS OUT TRAINEE DETAILS Sr. YRC TRADE_N SEAT_NO FIRST_N NAME LAST_N B_DATE PHY_ CASTE ADD1 ADD2 ADD3 ADD4 PIN ITI_N TRIA GTOTAL RESULT No. HAND L_NO ARMATURE & MOTOR 1 2010 216811001 GOHEL JAGDISHKUMAR MADHAVBHAI 01/06/1987 NO SEBC SUTHAR FALIU AT&PO:-DAHEMI TA:-BORSAD DI:-ANAND 0 VASAD 1 533 P REWINDING ARMATURE & MOTOR 2 2010 216811002 JADAV DILIPKUMAR BHANUBHAI 04/09/1988 NO SEBC GANPATI CHOWK AT:-ZILOD TA:-ANKLAV DI:-ANAND 388510 VASAD 1 514 P REWINDING ARMATURE & MOTOR OPP-BHARAT 3 2010 216811003 KALASVA RAVINDRAKUMAR KALUBHAI 07/11/1993 NO ST AT:-BORSAD DI:-ANAND 0 VASAD 1 543 P REWINDING SAWMILL ARMATURE & MOTOR 4 2010 216811004 MALEK IMRANKHAN ANAVARBHAI 07/06/1991 NO GEN AT:-VADI FALIA PAMOL TA:-BORSAD DI:-ANAND 0 VASAD 1 593 P REWINDING ARMATURE & MOTOR 5 2010 216811005 PADHIYAR AMBUBHAI CHIMANBHAI 01/06/1991 NO GEN BHAGVAN NAGAR AT:-NAPAD TALPAD TA&DI:-ANAND 0 VASAD 1 564 P REWINDING ARMATURE & MOTOR 6 2010 216811007 PADHIYAR JAGDISHBHAI NATUBHAI 23/05/1992 NO GEN AMBAV PARAMA AT:-AMBAV TA:-ANKLAV DI:-ANAND 0 VASAD 1 568 P REWINDING ARMATURE & MOTOR 7 2010 216811008 PADHIYAR MAHESHBHAI GOVINDBHAI 22/12/1990 NO SEBC MOTIPURA AT:-JOSHIKUVA TA:-ANKLAV DI:-ANAND 0 VASAD 1 549 P REWINDING ARMATURE & MOTOR 8 2010 216811010 PADHIYAR SANJAYKUMAR CHANDUBHAI 13/08/1993 NO GEN PARAMA AT:-AMBAV TA:-ANKLAV DI:-ANAND 0 VASAD 1 619 P REWINDING ARMATURE & MOTOR OPP-ALMAC TA&DI:- 9 2010 216811011 PARMAR ALPESHBHAI KANUBHAI 03/11/1990 NO SC A.23,GANHNAGAR CHHANI ROAD 0 VASAD 1 545 P REWINDING COMPANY VADODARA ARMATURE & MOTOR -

International Journal of Advance Research in Engineering, Science

Impact Factor (SJIF): 3.632 International Journal of Advance Research in Engineering, Science & Technology e-ISSN: 2393-9877, p-ISSN: 2394-2444 Volume 3, Issue 10, October-2016 ENHANCEMENT OF PUBLIC BUS TRANSPORT SYSTEM – A CASE STUDY OF AVKUDA Vishal P. Khokhani1, Dr. L.B.Zala2, Prof. N.F.Umrigar3 1Post Graduate Student, BVM Engineering College, Vallabh Vidyanagar 2Professor &Head of Civil Engineering Department, BVM Engineering College, Vallabh Vidyanagar 3Assistant Professor, Civil Engineering Department, BVM Engineering College, Vallabh Vidyanagar Abstract — Public bus transport system is that phase of transportation engineering which deals with the planning, geometric design, facility and traffic operations of road , streets, highways, their networks, terminals, abutting lands, and relationships with other modes of transportation. Public bus transport services are generally based on regular operation of transit buses along a route calling at agreed bus stops according to a published public transport timetable. In this study various types of data carried out like, population data, boarding and alighting survey, household survey, public opinion survey, etc. Travel speed, travel time, load factor is also calculated in this boarding and alighting survey. Population forecasting is carried out by arithmetic increment method. From the collected data the highest average load factor is on route between station to vadtal, the highest average travel speed is on route between station to bandhani chokdi, the lowest travel time is on route between station to bakrol. Key words: Load factor, Travel Time, Travel Speed. I. INTRODUCTION Public bus transport system is that phase of transportation engineering which deals with the planning, geometric design, facility and traffic operations of roads, streets, highways, their networks, terminals, abutting lands, and relationships with other modes of transportation. -

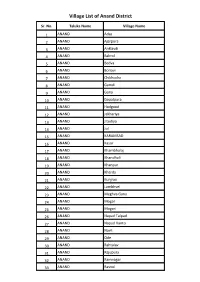

Village List of Anand District

Village List of Anand District Sr. No. Taluka Name Village Name 1 ANAND Adas 2 ANAND Ajarpura 3 ANAND Anklavdi 4 ANAND Bakrol 5 ANAND Bedva 6 ANAND Boriavi 7 ANAND Chikhodra 8 ANAND Gamdi 9 ANAND Gana 10 ANAND Gopalpura 11 ANAND Hadgood 12 ANAND Jakhariya 13 ANAND Jitodiya 14 ANAND Jol 15 ANAND KARAMSAD 16 ANAND Kasor 17 ANAND Khambholaj 18 ANAND Khandhali 19 ANAND Khanpur 20 ANAND Kherda 21 ANAND Kunjrao 22 ANAND Lambhvel 23 ANAND Meghva Gana 24 ANAND Mogar 25 ANAND Mogari 26 ANAND Napad Talpad 27 ANAND Napad Vanto 28 ANAND Navli 29 ANAND Ode 30 ANAND Rahtalav 31 ANAND Rajupura 32 ANAND Ramnagar 33 ANAND Rasnol 34 ANAND Samarkha 35 ANAND Sandesar 36 ANAND Sarsa 37 ANAND Sundan 38 ANAND Tarnol 39 ANAND Vadod 40 ANAND Vaghasi 41 ANAND Vaherakhadi 42 ANAND Valasan 43 ANAND Vans Khiliya 44 ANAND Vasad Village List of Petlad Taluka Sr. No. Taluka Name Village Name 1 PETLAD Agas 2 PETLAD Amod 3 PETLAD Ardi 4 PETLAD Ashi 5 PETLAD Bamroli 6 PETLAD Bandhani 7 PETLAD Bhalel 8 PETLAD Bhatiel 9 PETLAD Bhavanipura 10 PETLAD Bhurakui 11 PETLAD Boriya 12 PETLAD Changa 13 PETLAD Dantali 14 PETLAD Danteli 15 PETLAD Davalpura 16 PETLAD Demol 17 PETLAD Dhairyapura 18 PETLAD Dharmaj 19 PETLAD Fangani 20 PETLAD Ghunteli 21 PETLAD Isarama 22 PETLAD Jesarva 23 PETLAD Jogan 24 PETLAD Kaniya 25 PETLAD Khadana 26 PETLAD Lakkadpura 27 PETLAD Mahelav 28 PETLAD Manej 29 PETLAD Manpura 30 PETLAD Morad 31 PETLAD Nar 32 PETLAD Padgol 33 PETLAD Palaj 34 PETLAD Pandoli 35 PETLAD Petlad 36 PETLAD Porda 37 PETLAD Ramodadi 38 PETLAD Rangaipura 39 PETLAD Ravipura 40 PETLAD Ravli 41 PETLAD Rupiyapura 42 PETLAD Sanjaya 43 PETLAD Sansej 44 PETLAD Shahpur 45 PETLAD Shekhadi 46 PETLAD Sihol 47 PETLAD Silvai 48 PETLAD Simarada 49 PETLAD Sunav 50 PETLAD Sundara 51 PETLAD Sundarana 52 PETLAD Vadadala 53 PETLAD Vatav 54 PETLAD Virol(Simarada) 55 PETLAD Vishnoli 56 PETLAD Vishrampura Village List of Borsad Taluka Sr. -

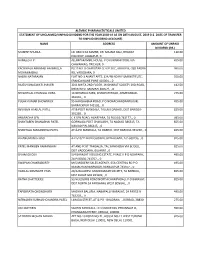

Name Address Amount of Unpaid Dividend (Rs.) Mukesh Shukla Lic Cbo‐3 Ka Samne, Dr

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2018‐19 AS ON 28TH AUGUST, 2019 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 110.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 495.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 KACHWALA ABBASALI HAJIMULLA PLOT NO. 8 CHAROTAR CO OP SOC, GROUP B, OLD PADRA 990.00 MOHMMADALI RD, VADODARA, 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 550.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 412.50 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 SEVANTILAL CHUNILAL VORA 14 NIHARIKA PARK, KHANPUR ROAD, AHMEDABAD‐ 275.00 381001, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 495.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 REVABEN HARILAL PATEL AT & POST MANDALA, TALUKA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐ 825.00 391230, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 495.00 SHANTABEN SHANABHAI PATEL GORWAGA POST CHAKLASHI, TA NADIAD 386315, TA 825.00 NADIAD PIN‐386315, , 0 SHANTILAL MAGANBHAI PATEL AT & PO MANDALA, TA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐391230, , 0 825.00 B HANUMANTH RAO 4‐2‐510/11 BADI CHOWDI, HYDERABAD, A P‐500195, , 0 825.00 PATEL MANIBEN RAMANBHAI AT AND POST TANDALJA, TAL.SANKHEDA VIA BODELI, 825.00 DIST VADODARA, GUJARAT., 0 SIVAM GHOSH 5/4 BARASAT HOUSING ESTATE, PHASE‐II P O NOAPARA, 495.00 24‐PAGS(N) 743707, , 0 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 495.00 -

CTRI Trial Data

PDF of Trial CTRI Website URL - http://ctri.nic.in Clinical Trial Details (PDF Generation Date :- Tue, 28 Sep 2021 00:09:43 GMT) CTRI Number CTRI/2021/01/030242 [Registered on: 05/01/2021] - Trial Registered Prospectively Last Modified On 04/01/2021 Post Graduate Thesis Yes Type of Trial Observational Type of Study Cross Sectional Study Study Design Other Public Title of Study Covid 19 among healthcare professionals Scientific Title of Multifactorial analysis of COVID 19 infection among healthcare professionals Study Secondary IDs if Any Secondary ID Identifier NIL NIL Details of Principal Details of Principal Investigator Investigator or overall Name Dr Bhalendu Vaishnav Trial Coordinator (multi-center study) Designation Professor and Head Affiliation Pramukhswami Medical College, Karamsad Address Department of Medicine, Pramukhswami Medical College, Shree Krishna Hospital, Karamsad Anand GUJARAT 388325 India Phone 02692228171 Fax Email [email protected] Details Contact Details Contact Person (Scientific Query) Person (Scientific Name Dr Bhalendu Vaishnav Query) Designation Professor and Head Affiliation Pramukhswami Medical College, Karamsad Address Department of Medicine, Pramukhswami Medical College, Shree Krishna Hospital, Karamsad Anand GUJARAT 388325 India Phone 02692228171 Fax Email [email protected] Details Contact Details Contact Person (Public Query) Person (Public Query) Name Dr BhoomiKUmar Patel Designation First year postgraduate student Affiliation Pramukhswami Medical College, Karamsad Address Department of Medicine, Pramukhswami Medical College, Shree Krishna Hospital, Karamsad Anand GUJARAT 388325 India Phone 02692228171 page 1 / 4 PDF of Trial CTRI Website URL - http://ctri.nic.in Fax Email [email protected] Source of Monetary or Source of Monetary or Material Support Material Support > Pramukhswami Medical College, Karamsad. -

Annual Report

Charutar Arogya Mandal A NNU A L R EPO R T 2 019 - 2 0 2 0 Contents 02 CAM Commitment 30 Fund Raising 02 Board of Trustees / Governors 34 Corporate Social Responsibility 04 Patient Care 36 Deh Daan and Donors 12 Medical Education 38 Accounts 22 Research 53 The Team 24 SPARSH & Community Extension 56 Gratitude CHARUTAR AROGYA MANDAL ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 I 1 CAM Commitment Charutar Arogya Mandal (CAM) is structured to reflect professionalism on the one hand and accountability to the community on the other. Registered as a Trust and Society, CAM’s properties Shri Nitinbhai R. Desai Shri Prayasvinbhai B. Patel Shri Atulbhai H. Dr. Vijaybhai Shri Vikrambhai Dr. Gauri Shri Mayurbhai are managed by a Board of Trustees and its policies Patel Patel Patel Surendra Trivedi Patel are decided by the Board of Governors headed by the Chairman. The Board has 18 members: 9 elected by the General body, 4 experts nominated by the Board, 3 senior officers of the Mandal, the Chairman of Charutar Vidya Mandal, and the President of Karamsad Municipal Borough. Dr. Amrita Patel Shri Jagrut H. Shri Tarak Patel Smt. Megha Shri Amit B. Patel Er. Bhikhubhai B. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Bhatt Shah Patel Patel Shri Nitinbhai R. Desai Shri Prayasvinbhai B. Patel Dr. Amrita Patel BOARD OF GOVERNORS Members Elected by the General Body Smt. Darshnaben Shri Sandeep Dr. Himanshu Shri Jeevan Shri Atulbhai H. Patel Patel Desai Pandya Kumar Akhouri Chairman Shri Jagrut H. Bhatt Secretary Dr. Vijaybhai Patel Shri Vikrambhai Patel Dr. Gauri Surendra Trivedi Shri Mayurbhai Patel Shri Sudhir Shri Keshav Dr. -

![[A] INSTITUTIONAL ETHICS COMMITTEE - 2 H M PATEL CENTRE for MEDICAL CARE and EDUCATION, KARAMSAD, GUJARAT](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0037/a-institutional-ethics-committee-2-h-m-patel-centre-for-medical-care-and-education-karamsad-gujarat-3260037.webp)

[A] INSTITUTIONAL ETHICS COMMITTEE - 2 H M PATEL CENTRE for MEDICAL CARE and EDUCATION, KARAMSAD, GUJARAT

Annexure 1 [a] INSTITUTIONAL ETHICS COMMITTEE - 2 H M PATEL CENTRE FOR MEDICAL CARE AND EDUCATION, KARAMSAD, GUJARAT Member Details [since 1st April, 2020] Sr. Name Qualification with Current Organization Telephone Number, e-mail address Designation/ Affiliation of Member No. specialization Fax Role of member in with Institute that has [02692 – 223660] Ethics Committee constituted the Ethics Committee 1 Dr. B G Patel M.Sc. (Medical), Advisor, +91 99040-94649 Chairperson None Ph.D., FIC, FGSA Charotar University of [email protected] [Pharmacologist/Basic Science and Technology, Medical Scientist] CHARUSAT Changa-388 421, District Anand Gujarat, India 2 Mrs. [Dr.] Nandita BA, MA, B.Ed., PhD Principal, Girls School, +91 9426468031 Deputy Chairperson None Shukla Bhadran, Anand [email protected] [Lay Person] 3 Dr. Dinesh Kumar MD Professor, Community +91 9662045484 Member Secretary Employee [Community Medicine, Pramukhswami [email protected] [Public Health Expert] Medicine] Medical College, Karamsad 4 Dr. Viral Patel MD Associate Professor, +91 9825060977 Member Employee [Radiodiagnosis] Department of [Clinician] [email protected] Radiodiagnosis, SK Hospital, Karamsad 5 Mr. Shailesh Panchal MSc Nursing Tutor, Nursing, +91 9879401720 Member Employee [Paediatric] GH Patel Institute of [email protected] [Nursing Faculty] Nursing, Karamsad Page 1 of 3 List of IEC - 2, Members, HMPCMCE Annexure 1 [a] INSTITUTIONAL ETHICS COMMITTEE - 2 H M PATEL CENTRE FOR MEDICAL CARE AND EDUCATION, KARAMSAD, GUJARAT 6 Mr. Nilesh M Panchal LLB, MLW Manager, Personnel and +91 9429254368 Member Employee Administration, Charutar [email protected] [Legal Expert] Arogya Mandal, Karamsad 7 Mr. Dharmendra N IRPM, MSW Medical Social Worker, +91 9879333135 Member Employee Shah Community Medicine, PS [email protected] [Social Scientist] Medical College, Karamsad 8 Dr. -

All College List GIA-SF

SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY AFFILIATED COLLEGES 1 Principal 2 Principal Anand Mercantile College of Science, AIMS College of Management & Technology Management & Computer Technology, AIMS Education Campus, Bhalej Road, Vadtal Road, Anand - 388 001. (SFI) Bakrol – 388 001. (SFI) 3 Principal 4 Principal Akhilesh Sureshbhai Patel Arts College, Anand Arts College, At. & Po. Boriavi – 387 310 Sh. Ramkrishna S eva Mandal , Ta. & Dist. Anand (SFI) Nr. Grid, Anand - 388 001 (GIA/SFI) 5 Principal 6 Principal Anand College of Education, Anand Commerce College, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva M andal, Nr. Town Hall, Anand - 388 001. (SFI) Nr. Town Hall, Anand - 388 001. (GIA/SFI) 7 Principal 8 Principal Anand Education College, Anand Homoeopathic Medical College & Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Research Institute, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Nr. Town Hall, Mandal, Nr. Sardar Baug, Anand - 388 001. (GIA) Anand - 388 001 (GIA) 9 Principal 10 Principal Anand Institute of P.G. Studies In Arts, Anand Institute of Business Studies, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Nr. Grid, Anand - 388 001 (SFI) Nr. Town Hall, Anand - 388 001. (SFI) 11 Principal 12 Principal Anand Institute of Social Work, Anand Law College, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Nr. Town Hall, Nr. Town Hall , Anand - 388 001. (SFI) Anand - 388 001. (GIA/SFI) 13 Principal 14 Principal Ashok & Rita Patel Institute of Integrated Study Bhikhabhai Jivabhai Vanijya Mahavidyalaya &Research In Biotechnology And Allied Sciences (BJVM), (ARIBAS), Opp. Vitthal Udyognagar-GIDC, Vallabh Vidyanagar - 388 120. (GIA/SFI) Behind Phase-IV GIDC, New Vallabh Vidyanagar - 388 121. (SFI) 15 Principal 16 Principal B.N. -

Paid Pending Applications As on Aug'19

PAID PENDING APPLICATIONS AS ON AUG'19 Circle: Anand Tentative Work Involved Sr Date Of Reg FQ Issue Date FQ Paid Date Month Of Scheme Sub Div Division Village Taluka District Name Load cat Remark No Work HT LT T/C Complition DD MM YYYY KM KM Cap DD MM YYYY DD MM YYYY V.V.NAGA 1 SPA Anand City Bakrol Anand Anand Malek Murtujahusen ayubmiya 10 8 10 2018 C 0.19 16 to 25 22 7 2019 23 7 2019 Sep-19 R V.V.NAGA 2 SPA Anand City Bakrol Anand Anand Patel Kanubhai Jashbhai 10 19 11 2018 B 0.025 0 22 7 2019 29 7 2019 Sep-19 R V.V.NAGA 3 SPA Anand City Bakrol Anand Anand Khureshi Asarafmiya Hasumiya 10 29 11 2018 C 0.17 10 to 16 22 7 2019 1 8 2019 Sep-19 R V.V.NAGA ANAND 4 SPA BAKROL Anand Anand PATEL JYOTIBEN NILESHBHAI 10 18 12 2018 D 0.08 10 KVA 22 7 2019 24 7 2019 Oct-19 R CITY 5 SPA Anand-S ANAND Khanpur Anand Anand Bhagvansinh Vakhatsinh Chakabhai Chauhan 10 18 5 2018 D 0.17 10 KVA 17 5 2019 11 6 2019 Sep-19 6 SPA Anand-S Anand Chikhodra Anand Anand Vasantbhai Ambalal Patel 15 2 7 2018 C 25 to 63 26 8 2019 27 8 2019 Sep-19 7 SPA Umreth-R Anand Chunel Mahudha Kheda Ravjibhai Bhikhabhai Prajapati 10 3 7 2018 D 0.63 10 KVA 25 6 2019 27 6 2019 Nov-19 Way problem 8 SPA Umreth-R Anand Parvata Umreth Anand Kesharbhai Chunabhai Rathod 7.5 9 7 2018 C 0.05 16 to 25 25 6 2019 11 7 2019 Sep-19 Standing paddy 9 SPA Umreth-R Anand Chunel Mahudha Kheda Pravinbhai Bhikhabhai Patel 7.5 19 7 2018 C 0.3 10 to 16 25 6 2019 2 7 2019 Nov-19 crop.photographs taken.