Ardeotis Kori)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Description of Copulation in the Kori Bustard J Ardeotis Kori

i David C. Lahti & Robert B. Payne 125 Bull. B.O.C. 2003 123(2) van Someren, V. G. L. 1918. A further contribution to the ornithology of Uganda (West Elgon and district). Novitates Zoologicae 25: 263-290. van Someren, V. G. L. 1922. Notes on the birds of East Africa. Novitates Zoologicae 29: 1-246. Sorenson, M. D. & Payne, R. B. 2001. A single ancient origin of brood parasitism in African finches: ,' implications for host-parasite coevolution. Evolution 55: 2550-2567. 1 Stevenson, T. & Fanshawe, J. 2002. Field guide to the birds of East Africa. T. & A. D. Poyser, London. Sushkin, P. P. 1927. On the anatomy and classification of the weaver-birds. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. Bull. 57: 1-32. Vernon, C. J. 1964. The breeding of the Cuckoo-weaver (Anomalospiza imberbis (Cabanis)) in southern Rhodesia. Ostrich 35: 260-263. Williams, J. G. & Keith, G. S. 1962. A contribution to our knowledge of the Parasitic Weaver, Anomalospiza s imberbis. Bull. Brit. Orn. Cl. 82: 141-142. Address: Museum of Zoology and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of " > Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, U.S.A. email: [email protected]. 1 © British Ornithologists' Club 2003 I A description of copulation in the Kori Bustard j Ardeotis kori struthiunculus \ by Sara Hallager Received 30 May 2002 i Bustards are an Old World family with 25 species in 6 genera (Johnsgard 1991). ? Medium to large ground-dwelling birds, they inhabit the open plains and semi-desert \ regions of Africa, Australia and Eurasia. The International Union for Conservation | of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Animals lists four f species of bustard as Endangered, one as Vulnerable and an additional six as Near- l Threatened, although some species have scarcely been studied and so their true I conservation status is unknown. -

The Bustards the Bustards

EndangeredEndangered BirdsBirds ofof BOTSWANA:BOTSWANA: TheThe BustardsBustards Commemorative Stamp Issue: August 2017 BOTSWANA BOTSWANA P5.00 P7.00 KATLEGO BALOI KATLEGO KATLEGO BALOI KATLEGO Red-crested Korhaan & Black-Bellied Bustard Northern Black Korhaan BOTSWANA BOTSWANA P9.00 P10.00 O R O B N E A G KATLEGO BALOI KATLEGO 0 7 BALOI KATLEGO 1 . 0 8 . 1 Denham’s Bustard Ludwig’s Bustard Endangered Birds of Botswana THE BUSTARDS ORDER: Otidiformes FAMILY: Otididae Bustards are large terrestrial birds mainly associated with dry open country and steppes in the Old World. They are omnivorous and nest on the ground. They walk steadily on strong legs and big toes, pecking for food as they go. They have long broad wings with “fingered” wingtips and striking patterns in flight. Many have interesting mating displays. (source: Wikipedia) DID YOU KNOW? The national bird of Botswana is the Kori Bustard KGORI /KORI BUSTARD/ Ardeotis kori and Chick Kori Bustard B 50t Botswana’s national bird. These bustards are the O largest and heaviest of the worlds’ flying birds. T S Found in open treeless areas throughout Botswana, W A they unfortunately have become scarce outside N protected areas, largely because people still kill A KATLEGO BALOI them to eat, despite it being illegal to hunt Kori Bustards in Botswana. They walk over the ground with long strides rather than to fly; indeed, results of satellite tracking in Central Kalahari Game Reserve showed most birds hardly moved beyond a 20 km radius in 2 years! (NO SPECIFIC SETSWANA NAME)/BLACK-BELLIED BOTSWANA KOORHAN/ Lissotis melanogaster P5.00 This bustard is found only in northern Botswana. -

The Eco-Ethology of the Karoo Korhaan Eupodotis Virgorsil

THE ECO-ETHOLOGY OF THE KAROO KORHAAN EUPODOTIS VIGORSII. BY M.G.BOOBYER University of Cape Town SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE (ORNITHOLOGY) UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN RONDEBOSCH 7700 CAPE TOWN The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town University of Cape Town PREFACE The study of the Karoo Korhaan allowed me a far broader insight in to the Karoo than would otherwise have been possible. The vast openness of the Karoo is a monotony to those who have not stopped and looked. Many people were instrumental in not only encouraging me to stop and look but also in teaching me to see. The farmers on whose land I worked are to be applauded for their unquestioning approval of my activities and general enthusiasm for studies concerning the veld and I am particularly grateful to Mnr. and Mev. Obermayer (Hebron/Merino), Mnr. and Mev. Steenkamp (Inverdoorn), Mnr. Bothma (Excelsior) and Mnr. Van der Merwe. Alwyn and Joan Pienaar of Bokvlei have my deepest gratitude for their generous hospitality and firm friendship. Richard and Sue Dean were a constant source of inspiration throughout the study and their diligence and enthusiasm in the field is an example to us all. -

Conservation Strategy and Action Plan for the Great Bustard (Otis Tarda) in Morocco 2016–2025

Conservation Strategy and Action Plan for the Great Bustard (Otis tarda) in Morocco 2016–2025 IUCN Bustard Specialist Group About IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN’s work focuses on valuing and conserving nature, ensuring effective and equitable governance of its use, and deploying nature- based solutions to global challenges in climate, food and development. IUCN supports scientific research, manages field projects all over the world, and brings governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,200 government and NGO Members and almost 11,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by over 1,000 staff in 45 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org About the IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation The IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation was opened in October 2001 with the core support of the Spanish Ministry of Environment, the regional Government of Junta de Andalucía and the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation and Development (AECID). The mission of IUCN-Med is to influence, encourage and assist Mediterranean societies to conserve and sustainably use natural resources in the region, working with IUCN members and cooperating with all those sharing the same objectives of IUCN. www.iucn.org/mediterranean About the IUCN Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of 9,000 experts. -

![Chlamydotis [Undulata] Macqueenii) in Saudi Arabia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4010/chlamydotis-undulata-macqueenii-in-saudi-arabia-394010.webp)

Chlamydotis [Undulata] Macqueenii) in Saudi Arabia

7. Display behaviour of breeding male Asiatic houbara (Chlamydotis [undulata] macqueenii) in Saudi Arabia Abstract Male Asiatic houbara (Chlamydotis [undulata] macqueenii) give spectacular visual displays, which may function as truthful advertising of fitness, and allow females to choose suitable partners. I examined whether a pre-condition for female choice – variation in male display intensity – exists in a houbara population in Mahazat as-Sayd Reserve, west central Saudi Arabia. Five key behavioural components of displays from 12 known-age males were sampled regularly over three breeding seasons from 1996 to 1998. On 100 occasions, a total of 570 running displays, 497 inter-display periods, all occurrence of feather flashing displays and feeding, and the distance covered during displays, were recorded. In addition, previously unrecorded details on the pattern and timing of male displays, and interactions between displaying houbara and other houbara, and with other species were described. Males were ranked based on the intensity of each behaviour each year, and on a combined rank for all behaviours. Intensity of male display differed among males in all years for all behaviours except distance ran during displays in 1997. Some males consistently ranked highly for all behaviours and in all years, whereas other males gave long display runs with short inter-display periods, but covered very little distance. Two strategies for performing displays that vary in intensity are suggested. There was no clear relationship between display intensity and male age or experience: in some years, the youngest, most inexperienced males gave the most intense displays. I conclude that the prediction that males vary in their display intensity was supported, and this allows opportunities for future researchers to examine whether the highest ranked males gain more matings with females than do lower ranking males. -

Status, Threats and Conservation of the Great

RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS assuring high pollen availability to the A-line plants till aphrodisiac value, the species is close to extinction from their peak flowering. its native haunts. Therefore, investigative surveys were These results verify our earlier findings1 in case of hy- done in its potential areas in Cholistan. Forty-four per- brid seed production of KBSH-1. A genotypic difference tinent people and 59 active hunting groups were inter- between the R line in these two hybrids did not show any viewed in order to assess the status of the species and the problems linked with its exploitation and conser- difference in flowering in response to similar treatments. vation. The results revealed that the population is on a Hastening of flowering following GA3 treatment to the 2 3 continuous decline. In about four years, nearly 49 out seeds in sorghum and rice , and nitrogen to pearl millet of 63 birds sighted were killed. The bird is under in- 4 and sorghum was reported. Hydration of seeds before tense pressure of human persecution and trade. The sowing had preponed flowering in maize variety5 and pa- study further highlights the implications needed to re- rental lines of hybrid, Sartaj6. Therefore, it can also be verse the fast extinction rate of the GIB from the concluded that seed priming with GA3 and application of province in particular and the country in general. urea (1%) as spray can be recommended as an effective technology for manipulation (preponement) of flowering Keywords: Conservation, Great Indian Bustard, status, of late parent to achieve perfect synchrony for economic threat. -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Ghana

Avibase Page 1of 24 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Ghana 2 Number of species: 773 3 Number of endemics: 0 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of globally threatened species: 26 6 Number of extinct species: 0 7 Number of introduced species: 1 8 Date last reviewed: 2019-11-10 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Ghana. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=gh [26/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Wildlife Conservation Strategies and Management in India: an Overview

Wildlife Conservation Strategies and Management in India: An Overview SWARNDEEP S. HUNDAL Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, 141 004, India, email [email protected] Key Words: wildlife management, wildlife conservation, species recovery, blackbuck, Indian antelope, Antilope cervicapra, royal Bengal tiger, Panthera tigris tigris, gangetic gharial, Gavialis gangeticus, great Indian bustard, Ardeotis nigriceps, India Introduction Wildlife resources constitute a vital link in the survival of the human species and have been a subject of much fascination, interest, and research all over the world. Today, when wildlife habitats are under severe pressure and a large number of species of wild fauna have become endangered, the effective conservation of wild animals is of great significance. Because every one of us depends on plants and animals for all vital components of our welfare, it is more than a matter of convenience that they continue to exist; it is a matter of life and death. Being living units of the ecosystem, plants and animals contribute to human welfare by providing • material benefit to human life; • knowledge about genetic resources and their preservation; and • significant contributions to the enjoyment of life (e.g., recreation). Human society depends on genetic resources for virtually all of its food; nearly half of its medicines; much of its clothing; in some regions, all of its fuel and building materials; and part of its mental and spiritual welfare. Considering the way we are galloping ahead, oblivious of what legacy we plan to leave for future generations, the future does not seem too bright. Statisticians have projected that by 2020, the human population will have increased by more than half, and the arable fertile land and tropical forests will be less than half of what they are today. -

South Africa Mega Birding Tour I 6Th to 30Th January 2018 (25 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding Tour I 6th to 30th January 2018 (25 days) Trip Report Aardvark by Mike Bacon Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Wayne Jones Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to South Africa Trip Report – RBT South Africa - Mega I 2018 2 Tour Summary The beauty of South Africa lies in its richness of habitats, from the coastal forests in the east, through subalpine mountain ranges and the arid Karoo to fynbos in the south. We explored all of these and more during our 25-day adventure across the country. Highlights were many and included Orange River Francolin, thousands of Cape Gannets, multiple Secretarybirds, stunning Knysna Turaco, Ground Woodpecker, Botha’s Lark, Bush Blackcap, Cape Parrot, Aardvark, Aardwolf, Caracal, Oribi and Giant Bullfrog, along with spectacular scenery, great food and excellent accommodation throughout. ___________________________________________________________________________________ Despite havoc-wreaking weather that delayed flights on the other side of the world, everyone managed to arrive (just!) in South Africa for the start of our keenly-awaited tour. We began our 25-day cross-country exploration with a drive along Zaagkuildrift Road. This unassuming stretch of dirt road is well-known in local birding circles and can offer up a wide range of species thanks to its variety of habitats – which include open grassland, acacia woodland, wetlands and a seasonal floodplain. After locating a handsome male Northern Black Korhaan and African Wattled Lapwings, a Northern Black Korhaan by Glen Valentine -

Scf Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey

SCF PAN SAHARA WILDLIFE SURVEY PSWS Technical Report 12 SUMMARY OF RESULTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE PILOT PHASE OF THE PAN SAHARA WILDLIFE SURVEY 2009-2012 November 2012 Dr Tim Wacher & Mr John Newby REPORT TITLE Wacher, T. & Newby, J. 2012. Summary of results and achievements of the Pilot Phase of the Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey 2009-2012. SCF PSWS Technical Report 12. Sahara Conservation Fund. ii + 26 pp. + Annexes. AUTHORS Dr Tim Wacher (SCF/Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey & Zoological Society of London) Mr John Newby (Sahara Conservation Fund) COVER PICTURE New-born dorcas gazelle in the Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim Game Reserve, Chad. Photo credit: Tim Wacher/ZSL. SPONSORS AND PARTNERS Funding and support for the work described in this report was provided by: • His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi • Emirates Center for Wildlife Propagation (ECWP) • International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC) • Sahara Conservation Fund (SCF) • Zoological Society of London (ZSL) • Ministère de l’Environnement et de la Lutte Contre la Désertification (Niger) • Ministère de l’Environnement et des Ressources Halieutiques (Chad) • Direction de la Chasse, Faune et Aires Protégées (Niger) • Direction des Parcs Nationaux, Réserves de Faune et de la Chasse (Chad) • Direction Générale des Forêts (Tunis) • Projet Antilopes Sahélo-Sahariennes (Niger) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Sahara Conservation Fund sincerely thanks HH Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, for his interest and generosity in funding the Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey through the Emirates Centre for Wildlife Propagation (ECWP) and the International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC). This project is carried out in association with the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). -

Australia's Biodiversity and Climate Change

Australia’s Biodiversity and Climate Change A strategic assessment of the vulnerability of Australia’s biodiversity to climate change A report to the Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council commissioned by the Australian Government. Prepared by the Biodiversity and Climate Change Expert Advisory Group: Will Steffen, Andrew A Burbidge, Lesley Hughes, Roger Kitching, David Lindenmayer, Warren Musgrave, Mark Stafford Smith and Patricia A Werner © Commonwealth of Australia 2009 ISBN 978-1-921298-67-7 Published in pre-publication form as a non-printable PDF at www.climatechange.gov.au by the Department of Climate Change. It will be published in hard copy by CSIRO publishing. For more information please email [email protected] This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the: Commonwealth Copyright Administration Attorney-General's Department 3-5 National Circuit BARTON ACT 2600 Email: [email protected] Or online at: http://www.ag.gov.au Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for Climate Change and Water and the Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts. Citation The book should be cited as: Steffen W, Burbidge AA, Hughes L, Kitching R, Lindenmayer D, Musgrave W, Stafford Smith M and Werner PA (2009) Australia’s biodiversity and climate change: a strategic assessment of the vulnerability of Australia’s biodiversity to climate change. -

Namibia & the Okavango

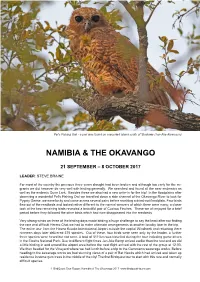

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen.