Charadrius Mongolus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies of the Foods and Feeding Ecology of Wading Birds

STUDIES OF THE FOODS AND FEEDING ECOLOGY OF WADING BIRDS Thesis submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Council for National Academic Awards .. by Malcolm E. Greenhalgh, B. A. Department of Biology Liverpool Polytechnic October 1975 s ABSTRACT In this thesis are described the populations of waders (Aves: Charadrii) occurring on the Ribble Estuary, Lancashire, special reference being made to the eleven species comprising the bulk of the shore wader population. The daily routine of these birds is described including the time spent in feeding. The feeding areas are described together with the foods taken from gut and pellet analysis and direct observation. The distributions of invertebrates, and especially those of major importance as wader food, are described as well as the factors affecting these distributions. Variations in density of prey in relation to O. D., general geography of the estuary, and time of year are included. Depth distribution and variations in prey size are outlined for the main species. Food intake was studied in the eight main waders. Daily intake through the year is described. in relation to energy requirements. Variations of feeding rates with several factors are included. All data are combined to enable calculation of the total biomasses of the main prey taken by waders in the course of a year. These are compared with total minimum annual production of the prey. Future work, including a computer study based on these and extra data, is outlined. Frontispiece a. The author counting a flock of 45,000 Knot 25 August, 1972 b. -

Migratory Shorebirds Management Plan

Report GLNG Curtis Island Marine Facilities Migratory Shorebirds Environmental Management Plan 17 MARCH 2011 Prepared for GLNG Operations Pty Ltd Level 22 Santos Place 32 Turbot Street Brisbane Qld 4000 42626727 Project Manager: URS Australia Pty Ltd Level 16, 240 Queen Street Angus McLeod Brisbane, QLD 4000 Senior Ecologist GPO Box 302, QLD 4001 Australia T: 61 7 3243 2111 Principal-In-Charge: F: 61 7 3243 2199 Chris Pigott Senior Principal Author: Angus McLeod Senior Ecologist Reviewer: Date: 17 March 2011 Reference: 42626727/01/03 Status: Final Chris Pratt Principal Environmental Scientist j:\jobs\42626727\5 works\draft emp\for tina 17.3.11\3310-glng-3-3 3-0065_shorebirds_final_17 03 2011.doc Table of Contents Abbreviations............................................................................................................iii Executive Summary..................................................................................................iv 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................1 1.1 Project Background .........................................................................................1 1.2 Purpose of the Migratory Shorebirds Environment Management Plan ...................................................................................................................1 1.3 Aims and Objectives ........................................................................................3 1.4 Study Area ........................................................................................................3 -

Meinmahla Kyun Wildlife Sanctuary Myanmar

Meinmahla Kyun Wildlife Sanctuary Myanmar EAAF NETWORK SITE CODE FOR OFFICE USE ONLY: E A A F 1 4 0 Site Information Sheet on East Asian-Australasian Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ 1 of 22 Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites | Meinmahla Kyun Wildlife Sanctuary [EAAF140] Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. -

<I>Actitis Hypoleucos</I>

Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos M. NICOLL 1 & P. KEMP 2 •c/o DundeeMuseum, Dundee, Tayside, UK 243 LochinverCrescent, Dundee, Tayside, UK Citation: Nicoll, M. & Kemp, P. 1983. Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos. Wader Study Group Bull. 37: 37-38. This note is intended to draw the attention of wader catch- and the old inner feathersare often retained (Pearson 1974). ers to the needfor carefulexamination of the primariesof Similarly, in Zimbabwe, first-year Common Sandpipers CommonSandpipers Actiris hypoleucos,and other waders, replacethe outerfive to sevenprimaries between December for partial primarywing moult. This is thoughtto be a diag- andApril (Tree 1974). It thusseems normal for first-spring/ nosticfeature of wadersin their first spring and summer summerCommon Sandpipers wintering in eastand southern (Tree 1974). Africa to show a contrast between new outer and old inner While membersof the Tay Ringing Group were mist- primaries.There is no informationfor birdswintering further nettingin Angus,Scotland, during early May 1980,a Com- north.However, there may be differencesin moult strategy mon Sandpiperdied accidentally.This bird was examined betweenwintering areas,since 3 of 23 juvenile Common and measured, noted as an adult, and then stored frozen un- Sandpiperscaught during autumn in Morocco had well- til it was skinned,'sexed', andthe gut contentsremoved for advancedprimary moult (Pienkowski et al. 1976). These analysis.Only duringskinning did we noticethat the outer birdswere moultingnormally, and so may have completed primarieswere fresh and unworn in comparisonto the faded a full primary moult during their first winter (M.W. Pien- and abradedinner primaries.The moult on both wingswas kowski, pers.comm.). -

Appendix M Migratory Bird Species Recorded in the Bing Bong - Mcarthur River Area

APPENDIX M MIGRATORY BIRD SPECIES RECORDED IN THE BING BONG - MCARTHUR RIVER AREA COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME RECORDED RECORDED EPBC ACT NORTHERN GROUP FEEDING AREA RECORDED FEEDING IN (Blakers IN (Chatto PROTECTED HEMISPHERE FOODS (Lane METHOD et al 1985) 2000,2001,20 MATTERS MIGRANTS 1987) 03) White-breasted Sea-Eagle Haliaeetus leucogaster x x x bird of prey open water Osprey Pandion haliaetus x bird of prey open water Little Tern Sterna albifrons x x seabird open water dive Bridled Tern Sterna anaethetus x seabird open water dive Lesser Crested Tern ^ Sterna bengalensis seabird open water dive Common Tern ^ Sterna hirundo x seabird open water dive Black-naped Tern Sterna sumatrana x x seabird open water dive Masked Booby ^ Sula dactylatra seabird open water dive Brown Booby * Sula leucogaster seabird open water dive Common Noddy * Anous stolidus seabird open water dive Least Frigatebird * Fregata ariel seabird open water Great Frigatebird * Fregata minor seabird open water Caspian Tern Hydroprogne caspia x x seabird open water dive Streaked Shearwater Puffinus leucomelas x seabird dive Little Curlew ^ Numenius minutus x x shorebird dry grassland insects, vegetable matter Greater Sand-Plover Charadrius leschenaultii x x shorebird intertidal mudflats crabs, marine visual, run worms, insects and peck Lesser Sand-Plover Charadrius mongolus x x shorebird intertidal mudflats crabs, molluscs, crustacea, worms Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus x x x shorebird intertidal mudflats crabs probe Grey Plover Pluvialis squatarola x x shorebird intertidal -

Some Aspects of Feeding Ecology of the Lesser Sand Plover Charadrius Mongolus in Three Different Zones in the Kadalundy Estuary, Kerala, South India

Feeding ecology of Lesser Sand Plover in Kerala, S India – K.M. Aarif Some Aspects of Feeding Ecology of the Lesser Sand Plover Charadrius mongolus in Three Different Zones in the Kadalundy Estuary, Kerala, South India K.M. AARIF Department of Zoology, Mananthavady Campus, Kannur University, Waynad District, Kerala, South INDIA. Email: [email protected] Received 24 October 2009; accepted 12 December 2009 Abstract: The study on feeding ecology of the Lesser Sand Plover (LSP) at Kadalundy estuary from July 2007 to December 2008, revealed that there were 13 species of crustaceans and 16 species of polychaete worms identified in the study area of which all identified small crab species(4 species) and polychaete worms (4 species) were consumed by LSPs. The highest number of crustacean species was found in mangroves (11 species). In contrast the highest species number of polychaete worms (13 species) was seen in the mudflats while no polychaete worm was identified in the sandy beds. Of the Crustaceans, Sesarma quadrata and Ocypoda sp. occurred in all the habitats. Sampling polychaete worms undertaken once a month showed that the number peaked at 39 in December 2008 in mudflats. Using direct observations once a week, the number of feeding birds was at its highest in December and January. Pearson correlation test showed significant relationship between the number of polychaete worms and feeding LSPs both at mudflats and mangroves ( p<0.05) and the Scheffe univariate test (ANOVA) showed significant differences between the three habitat zones ( p<0.01). The highest number of average total pecks at prey was seen at mudflats (82.1 in the morning and 128.0 in the afternoon). -

Migration Route for Greater and Lesser Sand Plovers Spending the Non-Breeding Season in Kenya

Biodiversity Observations http://bo.adu.org.za An electronic journal published by the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town The scope of Biodiversity Observations consists of papers describing observations about biodiversity in general, including animals, plants, algae and fungi. This includes observations of behaviour, breeding and flowering patterns, distributions and range extensions, foraging, food, movement, measurements, habitat and colouration/plumage variations. Biotic interactions such as pollination, fruit dispersal, herbivory and predation fall within the scope, as well as the use of indigenous and exotic species by humans. Observations of naturalised plants and animals will also be considered. Biodiversity Observations will also publish a variety of other interesting or relevant biodiversity material: reports of projects and conferences, annotated checklists for a site or region, specialist bibliographies, book reviews and any other appropriate material. Further details and guidelines to authors are on this website. Lead Editor: Arnold van der Westhuizen – Paper Editor: Les G Underhill CLUES TOWARDS THE MIGRATION ROUTE FOR GREATER AND LESSER SAND PLOVERS SPENDING THE NON-BREEDING SEASON IN KENYA Colin H.W. Jackson Recommended citation format: Jackson CHW 2016. Clues towards the migration route for Greater and Lesser Sand Plovers spending the non-breeding season in Kenya. Biodiversity Observations 7.36: 1–8. URL: http://bo.adu.org.za/content.php?id=229 Published online: 5 July 2016 – ISSN 2219-0341 – Biodiversity Observations 7.36: 1–8 1 MIGRATION breeds in north-western China (Hirschfield et al. 2000, Delany et al. 2009). CLUES TOWARDS THE MIGRATION ROUTE FOR In both species the adults return to their breeding grounds annually. -

First Record of the Terek Sandpiper in California

FIRST RECORD OF THE TEREK SANDPIPER IN CALIFORNIA ERIKA M. WILSON, 1400 S. BartonSt. #421, Arlington,Virginia 22204 BETTIE R. HARRIMAN, 5188 BittersweetLane, Oshkosh,Wisconsin 54901 On 28 August 1988, while birding at Carmel River State Beach, MontereyCounty, California(36032 ' N, 121057' W), we discoveredan adult Terek Sandpiper (Xenus cinereus). We watched this Eurasian vagrantbetween 1110 and 1135 PDT; we saw it again,along with local birders, between 1215 and 1240 as it foraged on the open beach. Wilson observedthe bird a third time on 5 September 1988 between 1000 and 1130; otherssaw it regularlyuntil 23 September1988. During our first observationa light overcastsky resultedin good viewingconditions, without glare or strongshadows. The weather was mild with a slightbreeze and some offshorefog. We found the Terek Sandpiperfeeding in the Carmel River'sshallow lagoon, separated from the Pacific Ocean by sand dunes. Its long, upturnedbill, quite out of keepingwith any smallwader with whichwe were familiar,immediately attracted our attention. We moved closer and tried unsuccessfullyto photographit. Shortlythereafter all the birdspresent took to the air. The sandpiperflew out over the dunesbut curvedback and landedout of sighton the open beach. We telephonedRobin Roberson,and half an hour later she, Brian Weed, Jan Scott, Bob Tinfie, and Ron Branson arrived,the lattertwo armedwith telephotolenses. We quicklyrelocated the TerekSandpiper on the beach,foraging at the surfline. The followingdescription is basedon our field notes,with color names takenfrom Smithe(197.5). Our bird was a medium-sizedsandpiper resemblinga winter-plumagedSpotted Sandpiper (Actitis rnacularia)but distinguishedby bright yellow-orangelegs and an upturnedbill (Figure1). The evenlycurved, dark horn bill, 1.5 timesthe lengthof the bird'shead, had a fleshyorange base. -

Terek Sandpiper (<I>Xenus Cinereis</I>): a First for Mexico

TerekSandpiper (Xenus cin s). a first for Mexico Daniel6alindo precipitationaveraging 200 mm (Garcia edge.The wingtipsextended backward 1964). to just reachthe tip of the tail. The un- CentroInterdisciplinario deCiencias Marinas On ll April 2002, Galindo locateda derpartswere white and unmarked.The TerekSandpiper (Xenus cinereus; Figure 1) legswere extremely bright yellowish-or- Av.Instituto Polit•cnico Nacional s/n at Chametla-El Centenario. This bird was ange.The lengthof the legs relativeto LaPaz, Baja California Sur23096 Mexico seenagain during late May 2002 Presum- the bird was shorter than that seen in ably the samebird wasrelocated there on most Tringaand approximatedthe pro- (email:[email protected]) 21 August 2002 and wasseen eleven more portionsof a SpottedSandpiper [Actitis times before it was last recorded 10 Febru- macularius]. The bill was long and ary 2003.The TerekSandpiper fed mostly curved upward. Its length was 1.5 to Steven(•. Mlodinow in the intertidalzone, usuallyin mixed 1.75 times that of the head. The bill was flocks of Semipalmated Plovers largelyblackish, excepting a smallarea 4819Gardner Avenue (Charadriussemipalmatus) and Western of brightorange at the base.Brief flight Sandpipers(Calidris mauri). On four occa- views revealeda thick white trailing Everett,Washington 98203 sions, it was observed roosting at the edgeto the secondariesthat extendedas supralittoralzone, amonga flock of Semi- a narrower whitish area onto the inner- (email:[email protected]) palmated Plovers. Throughout its stay,it mostseveral primaries. The rump and appearedto be in goodhealth, feeding and uppertailcoverts were gray, The rectrices flyingwithout apparent problems. were gray with whitish barringon the RobertoCarmona The followingis a descriptionof the En- outer portionof the outer web of each senadade La PazTerek Sandpiper based on rectrix(which provided a whitishouter LuisSauma fieldnotes and videotapeby SGMfrom 29 border to the tail as a whole). -

Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1

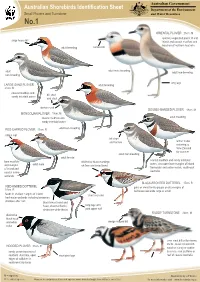

Australian Government Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1 ORIENTAL PLOVER 25cm. M sparsely vegetated plains of arid large heavy bill inland and coastal mudflats and beaches of northern Australia adult breeding narrow bill adult male breeding adult adult non-breeding non-breeding long legs LARGE SAND PLOVER adult breeding 21cm. M coastal mudflats and bill short sandy intertidal zones and stout darker mask DOUBLE-BANDED PLOVER 19cm. M MONGOLIAN PLOVER 19cm. M coastal mudflats and adult breeding sandy intertidal zones RED-CAPPED PLOVER 15cm. R adult non-breeding rufous cap bill short and narrow winter visitor returning to New Zealand for summer adult non-breeding adult female coastal mudflats and sandy intertidal bare mudflats distinctive black markings zones, also open bare margins of inland and margins adult male on face and breastband of inland and freshwater and saline marsh, south-east coastal saline Australia wetlands BLACK-FRONTED DOTTEREL 17cm. R RED-KNEED DOTTEREL pairs or small family groups on dry margins of 18cm. R feshwater wetlands large or small feeds in shallow margins of inland short rear end freshwater wetlands including temporary shallows after rain black breast band and head, chestnut flanks, long legs with distinctive white throat pink upper half RUDDY TURNSTONE 23cm. M distinctive black hood and white wedge shaped bill collar uses stout bill to flip stones, shells, seaweed and drift- 21cm. R HOODED PLOVER wood on sandy or cobble sandy ocean beaches of beaches, rock platform or southern Australia, open short pink legs reef of coastal Australia edges of saltlakes in south-west Australia M = migratory . -

Mapping Farmland Wader Distributions and Population Change to Identify Wader Priority Areas for Conservation and Management Action

Mapping farmland wader distributions and population change to identify wader priority areas for conservation and management action Scott Newey1*, Debbie Fielding1, and Mark Wilson2 1. The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen, AB15 8QH 2. The British Trust for Ornithology Scotland, Stirling, FK9 4NF * [email protected] Introduction Many birds have declined across Scotland and the UK as a whole (Balmer et al. 2013, Eaton et al. 2015, Foster et al. 2013, Harris et al. 2017). These include five species of farmland wader; oystercatcher, lapwing, curlew, redshank and snipe. All of these have all been listed as either red or amber species on the UK list of birds of conservation concern (Harris et al. 2017, Eaton et al. 2015). Between 1995 and 2016 both lapwing and curlew declined by more than 40% in the UK (Harris et al. 2017). The UK harbours an estimated 19-27% of the curlew’s global breeding population, and the curlew is arguably the most pressing bird conservation challenge in the UK (Brown et al. 2015). However, the causes of wader declines likely include habitat loss, alteration and homogenisation (associated strongly with agricultural intensification), and predation by generalist predators (Brown et al. 2015, van der Wal & Palmer 2008, Ainsworth et al. 2016). There has been a concerted effort to reverse wader declines through habitat management, wader sensitive farming practices and predator control, all of which are likely to benefit waders at the local scale. However, the extent and severity of wader population declines means that large scale, landscape level, collaborative actions are needed if these trends are to be halted or reversed across much of these species’ current (and former) ranges. -

Conservation Advice Charadrius Mongolus Lesser Sand Plover

THREATENED SPECIES SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Established under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 The Minister approved this conservation advice and included this species in the Endangered category, effective from 5 May 2016 Conservation Advice Charadrius mongolus Lesser sand plover Taxonomy Conventionally accepted as Charadrius mongolus Pallas, 1776. Charadriidae. Other common names include Mongolian plover, dotterel, sand-plover or sand-dotterel; lesser dotterel or sand-dotterel; short-nosed sand plover (Marchant & Higgins 1993). Two subspecies occur in Australia, Charadrius mongolus mongolus lesser sand plover (Mongolian) and C. m. stegmanni lesser sand plover (Kamchatkan). Taxonomic uniqueness: medium (11 genera/family, 35 species/genus, 5 subspecies/species; Garnett et al., 2011). Summary of assessment Conservation status Endangered: Criterion 1 A2 (a) The highest category for which Charadrius mongolus is eligible to be listed is Endangered. Charadrius mongolus has been found to be eligible for listing under the following listing categories: Criterion 1: A2 (a): Endangered Criterion 2: Not eligible Criterion 3: Not eligible Criterion 4: Not eligible Criterion 5: Not eligible Species can be listed as threatened under state and territory legislation. For information on the listing status of this species under relevant state or territory legislation, see http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Reason for conservation assessment by the Threatened Species Scientific Committee This advice follows assessment of new information provided to the Committee to list Charadrius mongolus. Public Consultation Notice of the proposed amendment and a consultation document was made available for public comment for 47 business days between 1 October and 4 December 2015.