Juniper Canyon, Wallula Gap: an “Oasis in the Desert”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods—Roadside Geology

u 0 by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF Natural Resources Jennifer M. Belcher - Commissioner of Public Lands Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor FLOOD BASALTS AND GLACIER FLOODS: Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor Division of Geology and Earth Resources WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Jennifer M. Belcher-Commissio11er of Public Lands Kaleeo Cottingham-Supervisor DMSION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Raymond Lasmanis-State Geologist J. Eric Schuster-Assistant State Geologist William S. Lingley, Jr.-Assistant State Geologist This report is available from: Publications Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources P.O. Box 47007 Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Price $ 3.24 Tax (WA residents only) ~ Total $ 3.50 Mail orders must be prepaid: please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks payable to the Department of Natural Resources. Front Cover: Palouse Falls (56 m high) in the canyon of the Palouse River. Printed oo recycled paper Printed io the United States of America Contents 1 General geology of southeastern Washington 1 Magnetic polarity 2 Geologic time 2 Columbia River Basalt Group 2 Tectonic features 5 Quaternary sedimentation 6 Road log 7 Further reading 7 Acknowledgments 8 Part 1 - Walla Walla to Palouse Falls (69.0 miles) 21 Part 2 - Palouse Falls to Lower Monumental Dam (27.0 miles) 26 Part 3 - Lower Monumental Dam to Ice Harbor Dam (38.7 miles) 33 Part 4 - Ice Harbor Dam to Wallula Gap (26.7 mi les) 38 Part 5 - Wallula Gap to Walla Walla (42.0 miles) 44 References cited ILLUSTRATIONS I Figure 1. -

Interior Columbia Basin Mollusk Species of Special Concern

Deixis l-4 consultants INTERIOR COLUMl3lA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN cryptomasfix magnidenfata (Pilsbly, 1940), x7.5 FINAL REPORT Contract #43-OEOO-4-9112 Prepared for: INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT PROJECT 112 East Poplar Street Walla Walla, WA 99362 TERRENCE J. FREST EDWARD J. JOHANNES January 15, 1995 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 ‘(206) 527-6764 INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN Terrence J. Frest & Edward J. Johannes Deixis Consultants 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 (206) 527-6764 January 15,1995 i Each shell, each crawling insect holds a rank important in the plan of Him who framed This scale of beings; holds a rank, which lost Would break the chain and leave behind a gap Which Nature’s self wcuid rue. -Stiiiingfieet, quoted in Tryon (1882) The fast word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: “what good is it?” If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. if the biota in the course of eons has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first rule of intelligent tinkering. -Aido Leopold Put the information you have uncovered to beneficial use. -Anonymous: fortune cookie from China Garden restaurant, Seattle, WA in this “business first” society that we have developed (and that we maintain), the promulgators and pragmatic apologists who favor a “single crop” approach, to enable a continuous “harvest” from the natural system that we have decimated in the name of profits, jobs, etc., are fairfy easy to find. -

Mid-Columbia River Fish Toxics Assessment: EPA Region 10 Report

EPA-910-R-17-002 March 2017 Mid-Columbia River Fish Toxics Assessment EPA Region 10 Report Authors: Lillian Herger, Lorraine Edmond, and Gretchen Hayslip U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10 www.epa.gov Mid-Columbia River Fish Toxics Assessment EPA Region 10 Report Authors: Lillian Herger, Lorraine Edmond, and Gretchen Hayslip March 2017 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10 1200 Sixth Avenue, Suite 900 Seattle, Washington 98101 Publication Number: EPA-910-R-17-002 Suggested Citation: Herger, L.G., L. Edmond, and G. Hayslip. 2016. Mid-Columbia River fish toxics assessment: EPA Region 10 Report. EPA-910-R-17-002. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10, Seattle, Washington. This document is available at: www.epa.gov/columbiariver/mid-columbia-river-fish toxics-assessment Mid-Columbia Toxics Assessment i Mid-Columbia Toxics Assessment List of Abbreviations Abbreviation Definition BZ# Congener numbers assigned by Ballschmiter and Zell CDF Cumulative Distribution Function CM Channel marker CR Columbia River DDD Dichloro-diphenyl-dichloroethane DDE Dichloro-diphenyl-dichloroethylene DDT Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane DO Dissolved Oxygen ECO Ecological EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency GIS Geographic Information System HH Human Health HCB Hexachlorobenzene HRGC/HRMS High Resolution Gas Chromatography / High Resolution Mass Spectrometry ICPMS Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry IDEQ Idaho Department of Environmental Quality LCR Lower Columbia River MCR Mid-Columbia River MDL Minimum detection limit NA Not Applicable ND Non-detected ODEQ Oregon Department of Environmental Quality ORP Oxidation-Reduction Potential PBDE Polybrominated diphenyl ether PCB Polychlorinated biphenyl QAPP Quality Assurance Project Plan QC Quality Control RARE Regional Applied Research Effort REMAP Regional Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Program S.E. -

Ideal Commercial Development Site in The

IDEAL COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT SITE IN THE TRI-CITIES RICHLAND, WASHINGTON EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Location Maps .......................................................................................................4 • Executive Summary..............................................................................................6 • Aerial........................................................................................................................7 MARKET ANALYSIS • Retail Market Description.....................................................................................8 • Retail Void Analysis...............................................................................................9 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION • Development Plan.................................................................................................10 • Roadways...............................................................................................................13 • Regional Map..........................................................................................................14 AREA OVERVIEW • Tri-Cities Facts.......................................................................................................15 • Quality of Life..........................................................................................................16 • Economy...................................................................................................................18 OF CONTENTS TABLE • Housing.....................................................................................................................19 -

Washington Geology Released Since [Project Chief: W

·- July 1983 Volume 11 Number 3 Washington Geologic Newsletter · . Lovitt mine, near Wenatchee, Chelan County, Washington, 1977. Photo by Jack Jansons BRIAN J . BOYLE COMMISSIONER OF PUBLIC LANDS ART STEARNS, Supervisor RAYMOND LASMANIS, State Geologist DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Marlin Woy - To Porllond n Exit IOs·• [" GEOLOGY ANO /. t Roctl)11onl•t ... Solllh EARTH ~CES i..-<-....<....<c.L..'-'-! !! 0 I u Sound .. C 'Entrance- Moll Elf!H~~• · 0Poulsot\S. Mortin\ s,. : ••••• ,Porklno .....~ :....... ----. ........... .................... • • • • •• • • • • Coll•o• Z ·········o····· ... 4224 6th Ave. S.E., Lacey, Washington in Albortson• MAILING ADDRESS: Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Olympia, WA 98504 (206) 459-6372 Field office address: Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Spokane County Agricultural Center N. 222 Havana Spokane, WA 99202 ( 509) 458-2038 Lauta Btay, Editor The Washington Geologic Newsletter, a quarterly report of geologlc articles, Ts published by the Division of Geology and Earth Resources, Department of Natural Resources. The newsletter is free upon request. The division also publishes bulletins, information circulars, and geologic maps. A list of these publicatiOflS will be sent upon request. .. THE WENATCHEE GOLD RUSH by Bonnie Bunning* INTRODUCTION from the D ''reef" between 1949 and 1967. For a long time the ore was shipped directly to the Tacoma smelter On March 4, 19831 when Breakwater Resources LLd. where a substantial credit for the siliceous ores (used as and Asamera Minerals, Inc., made their exciting gold find flux in the smelter) helped make t he mine profitable. In public, companies and individuals from Canada and the 1961, Day Mines, Inc., and Lovitt Mining Co. -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES Fall, 1984 2 The Wild Cascades PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE ONCE THE LINES ARE DRAWN, THE BATTLE IS NOT OVER The North Cascades Conservation Council has developed a reputation for consistent, hard-hitting, responsible action to protect wildland resources in the Washington Cascades. It is perhaps best known for leading the fight to preserve and protect the North Cascades in the North Cascades National Park, the Pasayten and Glacier Peak Wilderness Areas, and the Ross Lake and Lake Chelan National Recreation Areas. Despite the recent passage of the Washington Wilderness Act, many areas which deserve and require wilderness designation remain unprotected. One of the goals of the N3C must be to assure protection for these areas. In this issue of the Wild Cascades we have analyzed the Washington Wilderness Act to see what we won and what still hangs in the balance (page ). The N3C will continue to fight to establish new wilderness areas, but there is also a new challenge. Our expertise is increasingly being sought by government agencies to assist in developing appropriate management plans and to support them against attempts to undermine such plans. The invitation to participate more fully in management activities will require considerable effort, but it represents a challenge and an opportunity that cannot be ignored. If we are to meet this challenge we will need members who are either knowledgable or willing to learn about an issue and to guide the Board in its actions. The Spring issue of the Wild Cascades carried a center section with two requests: 1) volunteers to assist and guide the organization on various issues; and 2) payment of dues. -

Operation and Maintenance of the Umatilla Project and Umatilla Basin Project, Umatilla County

UNITED STA1ES OEPARlMENTOF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE West Coast Region 1201 NE Lloyd Boulevard , Su~e 1100 Portland, Oregon 97232-1274 July 2, 2019 Refer to NMFS No: WCR-2018-10032 Dawn Wiedmeier Area Manager Columbia-Cascades Area Office U.S. Bureau of Reclamation 1917 Marsh Road Yakima, Washington 98901 Re: Endangered Species Act Section 7(a)(2) Biological Opinion and Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act Essential Fish Habitat Consultation on Operation and Maintenance of the Umatilla Project and Umatilla Basin Project, Umatilla County. Oregon, HUC 17070103 (Umatilla), HUC 17070101 (Columbia-Lake Wallula). Enclosed is a biological opinion (opinion) prepared by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) pursuant to section 7(a)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) on the effects of operating the Umatilla Project and the Umatilla Basin Project in Umatilla County, Oregon. NMFS concludes in this opinion that the operation of the Umatilla and Umatilla Basin Projects is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of the following ESA-listed species: Middle Columbia River steelhead Upper Columbia River steelhead Snake River Basin steelhead Snake River sockeye salmon Upper Columbia River spring-run Chinook salmon Snake River spring/summer-run Chinook salmon Snake River fall-run Chinook salmon NMFS also concludes that the proposed action is not likely to destroy or adversely modify designated critical habitat. As required by section 7 of the ESA, NMFS included reasonable and prudent measures with nondiscretionary terms and conditions that NMFS believes are necessary to avoid or minimize the effect of incidental take caused by this action. -

Walla Walla Subbasin Assessment

Walla Walla Subbasin Assessment General Overview Components Prepared by: Walla Walla Basin Watershed Council Version 2: April 2004 Note: This document was not reviewed or approved by the Subbasin Planning Team, subbasin plan leads, co-managers, or subbasin technical staff. 1 Introduction History and Description of Planning Entity The organization for developing the Walla Walla River Subbasin Plan was comprised of the lead agencies, subcontractors, the Planning Team, the Technical Team, and other governmental and non-governmental organizations that will provide local input. The role of each member group is described below. Lead Agencies and Co-Lead Agency The lead agency for the Oregon portion of the Walla Walla subbasin was the Walla Walla Basin Watershed Council, with the Walla Walla Watershed Foundation serving as its fiscal agent. The co-lead entity for the Washington portion of the subbasin was Walla Walla County. The responsibility of co-leads was to oversee and initiate the planning process and ensure that it was an open and inclusive and there was proper outreach to and input from subbasin stakeholders. Subcontractors The Co-lead entities subcontracted with consultant(s) to perform the following functions: (1) facilitation assistance, (2) public involvement assistance, and (3) report preparation including technical assistance. The consultants’ roles were to facilitate and assist with the coordination of Technical and Planning Team and Working Group meetings. The consultants worked closely with the Technical and Planning Teams and the Working Group, and compiled, edited, and wrote (as appropriate) various sections of all draft and final versions of the assessment, inventory, and management plan components of the subbasin plan. -

Chapter 7. Parks and Recreation Element

1 Chapter 7. Parks and Recreation Element 2 7.1. Introduction 3 Parks, recreational facilities, and open space are generally considered beneficial resources and 4 essential contributors to a community’s quality of life. Located within the County are a number 5 of different types of parks and recreational facilities. 6 The County has not traditionally served as a provider of park and recreation facilities. Local 7 cities, private agencies, federal agencies, and schools have an established history of furnishing 8 these services. 9 The purpose of this element is to evaluate parks and recreation facilities in the County and to 10 develop goals and policies that guide management and coordination of them. 11 7.1.1. Applicable Growth Management Act Goals 12 GMA planning goals that are applicable to the Parks and Recreation Element include the 13 following: 14 . Open space and recreation. Retain open space, enhance recreational opportunities, conserve 15 fish and wildlife habitat, increase access to natural resource lands and water, and develop 16 parks and recreation facilities (Revised Code of Washington [RCW] 36.70A.020(9)). 17 . Public facilities and services. Ensure that those public facilities and services necessary to 18 support development shall be adequate to serve the development at the time the development 19 is available for occupancy and use without decreasing current service levels below locally 20 established minimum standards (RCW 36.70A.020(12)). 21 . Historic preservation. Identify and encourage the preservation of lands, sites, and structures 22 that have historical or archaeological significance (RCW 36.70A.020(13)). 23 Goals described in the Shoreline Management Act (SMA) also support the Parks and Recreation 24 Element. -

INTERIOR/GEOLOGICAL SURVEY USGS· INF -72- 2 !R I) - Electric City-Grand Coulee, Washington the CHANNELED SCABLANDS of EASTERN WASHINGTON

9 INTERIOR/GEOLOGICAL SURVEY USGS· INF -72- 2 !R I) - Electric City-Grand Coulee, Washington THE CHANNELED SCABLANDS OF EASTERN WASHINGTON - The Geologic Story of the Spokane Flood- '(( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE , 1976 0 -208-172 F'or sale by the uperint.endent. of Documents, .S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.. 20402- Pric~ 70 cents Lock No. 024 - 001-02507- I nL nlog o. I 19.2: W27/6/974 There is n minimum charge of $1.00 for each mail order A trave ler enterin g th e tal f W as hington fro m th e Eas t crosses a flat-to-rolling country sid o f deep, fertil so il commonly sown with w heat. ontinuing wes twa rd , he abruptly nters a d eply scar red land o f bare bl a k ro k ut by labyrin thine ca nyons and chann el , plunge pools and ro k bas in s, ca ca de and ca tara t ledges, and di playi ng ragged buttes and li ffs, alcoves, im men e gravel bars, and giant ripple marks. Th e traveler has reached the starkly sceni " Chan neled cab lands," and this d ramatic hange in th e landscape may well ca use him to w onder " w hat happ n d here? " Th e answ er- th e grea te t fl ood documented by man. This publica tion, summari zin g th e equence of geologic events that culminated in th e so-call ed ''Spokan Fl ood," w as prepar d in res ponse to a ge neral int re t in geology and a particul ar interes t in th e o ri gin of th e Scab land o ften ex pre sed by th ose ross in g th e State of W as hington. -

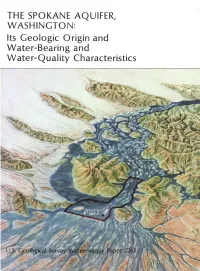

THE SPOKANE AQUIFER, WASHINGTON: Its Geologic Origin

THE SPOKANE AQUIFER, WASHINGTON: Its Geologic Origin and Water-Bearing and Water-Quality Characteristics Cover: Aerial view of the Spokane Flood sweep ing southwesterly across the study area (outlined in red) and vicinity. THE SPOKANE AQUIFER, WASHINGTON: Its Geologic Origin and Water-Bearing and Water-Quality Characteristics By Dee Molenaar U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 2265 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAULHODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1988 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section, U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Molenaar, Dee. The Spokane aquifer, Washington. (U.S. Geological Survey water-supply paper; 2265) Bibliography: p. Supt.ofDocs.no. : 119.13:2265 1. Aquifers Washington (State) Spokane Region. I. Title. II. Series. GB1199.3.W2M651987 553.7'9'0979737 84-600259 PREFACE: WHY THIS REPORT WAS WRITTEN This report was prepared to provide a non The description of the Spokane aquifer technical description and understanding of the includes the geologic story behind its origin Spokane aquifer, one of the world's most pro and its part in the Spokane Valley's hydrologic ductive water-bearing formations. Because the setting. Discussed are the relation among pre aquifer also has a most fascinating geologic ori cipitation over the area (mostly in the head gin, a discussion of the geologic story of the waters of the Spokane River basin), the flow of Spokane area is presented. This should enhance the Spokane River, and the movement of the reader's appreciation of the natural proces water to, through, and from the aquifer. -

3.7-1 3.7 Visual Quality and Noise 3.7.1 Affected Environment 3.7.1.1

3.7 Visual Quality and Noise 3.7.1 Affected Environment 3.7.1.1 Visual Quality The project site is located in a rural area on a relatively flat bluff about 150 feet above the Columbia River. The site is characterized by basalt outcrops, shrub-steppe habitat, and wetlands, with some scattered trees. The views to the north are of the wide Columbia River (Lake Wallula) and croplands, rangeland, shrub-steppe habitat, and scattered agricultural residences and buildings on the Washington State side of the river. The views to the east also are of the Columbia River and shrub-steppe habitat on the Oregon side of the river. To the south, high brush and smaller trees diversify the view of the surrounding landscape. To the west lies similar shrub-steppe habitat but the view is dominated by the TRCI, a large medium custody facility located about 1.5 miles west of the project site. The facility is an industrial-looking 650,000-square-foot concrete facility surrounded by tall fences with a guardhouse at the entrance. This facility is well-lit and visible at night. The existing and proposed electrical transmission line and natural gas supply/wastewater discharge pipeline route is comprised of rural residences, irrigated croplands, non-irrigated croplands, grazing land, and low-growing shrub-steppe land. 3.7.1.2 Noise The existing sound levels in the project area are characterized by rural, ambient/background noises. The closest potential noise source or receptor is the TRCI, located about 1.5 miles west of the project site. Although the background noise levels were not measured, it was estimated that they were in the 35- to 40-decibel range during a site visit.