The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project HARRY A. CAHILL Interviewed By: Charles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customized Power Playlist

CUSTOMIZED POWER PLAYLIST Move to the right beats per minute and you just might amp up your performance. Here’s how to match your music to your workout. Matching Your Music to Your Workout Fill up your mp3 with the new tunes below that perfectly suit your activity type. You can go a step further, too, and match the beats per minute (BPM) of the music to the heart rate you expect to reach during that workout. What should that be? This can vary greatly from person to person, but as a guideline, power walking songs would have about 135-140 BPM — you’ll want a lower BPM if you’re just getting started doing activity or when you’re doing a warm-up or cool-down. In comparison, running songs might be around 147-165 BPM. With the slow songs here (80 BPM or so), you have a choice — you can use them as cool-downs or can really push yourself and walk/bike/ swim twice as fast as the beat. Here, we’ve created lists of mostly lower BPM music so you can get pumped up without overdoing it. So which music can fill out your perfect activity playlist? Check out the suggestions below and add any that appeal to you to your next activity session. INDIVIDUALIST This playlist should help you lace up your shoes and get in your groove. It’s full of up-tempo songs, with four-on-the floor beats that’ll keep you moving. These songs are great if you’re just starting to get active; they’re all within the 125-130 BPM range so you can keep a steady pace. -

Come & Get It<Span Class="Orangetitle"> Deconstructed

Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com Come & Get It Deconstructed Skip to: Audio/Video At a Glance Song Overview Structural Analysis Momentum/Tension/Intensity (MTI) Lyrics & Harmonic Progression The Music The Vocal Melody Primary Instrumentation, Tone & Mix Compositional Assessment Hit Factor Assessment Conclusion Why it’s a Hit Songwriter/Producer Take Aways Audio/Video Back to Top At a Glance Back to Top Artist: Selena Gomez Song/Album: Come & Get It / Stars Dance Songwriters: Dean, Eriksen, Hermansen Genre: Pop Sub Genre: Electropop, World (Indian) Length: 3:52 Structure: B-A-B-A-B-C-B Tempo: 80 bpm First Chorus: 0:15 / 6% into the song Intro Length: 0:15 Outro Length: n/a Electric vs. Acoustic: Electric Primary Instrumentation: Synth Lyrical Theme: Love/Relationships Title Occurrences: Come & Get It occurs 12 times within the song Primary Lyrical P.O.V: 1st & 2nd Song Overview Back to Top Released as the lead single from her first solo album, Stars Dance, Come & Get It finds Selena Gomez teaming up with 3 of today’s hottest hitmakers including Tor Hermansen & Mikkel Eriksen (both of Stargate), and Ester Dean with the aim of separating her from her Disney 1 / 71 Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com past and to establish her as a major force within the mainstream Pop scene alongside contemporaries including Rihanna, Katy and Britney. As you’ll see within the report, Come & Get It possesses many of the “hit qualities” that are indicative of today’s chart-topping songs, but it also falls short in some key areas that preclude it from realizing its fullest potential. -

Inside Official Singles & Albums • Airplay Charts

ChartPack cover_v3_News and Playlists 08/04/13 13:56 Page 35 CHARTPACK Duke Dumont is at No.1 in the Official Singles Chart this week with Need U (100%) feat A*M*E & MNEK - as Justin Timberlake returns to the albums summit INSIDE OFFICIAL SINGLES & ALBUMS • AIRPLAY CHARTS • COMPILATIONS & INDIE CHARTS 52-53 Singles-Albums_v1_News and Playlists 08/04/13 11:33 Page 28 CHARTS UK SINGLES WEEK 14 For all charts and credits queries email [email protected]. Any changes to credits, etc, must be notified to us by Monday morning to ensure correction in that week’s printed issue The Official UK Singles and Albums Charts are produced by the Official Charts Company, based on a sample of more than 4,000 record outlets. They are compiled from actual sales last Sunday to Saturday, THE OFFICIAL UK SINGLES CHART THIS LAST WKS ON ARTIST / TITLE / LABEL CATALOGUE NUMBER (DISTRIBUTOR) THIS LAST WKS ON ARTIST / TITLE / LABEL CATALOGUE NUMBER (DISTRIBUTOR) WK WK CHRT (PRODUCER) PUBLISHER (WRITER) WK WK CHRT (PRODUCER) PUBLISHER (WRITER) 1 DUKE DUMONT FEAT. A*M*E & MNEK Need U (100%) MoS/Blas? Boys Club GBCEN1300001 (ARV) 39 29 8 BAAUER Harlem Shake Mad Decent USZ4V1200043 (C) N (Duke Dumont/Forrest) EMI/Kobalt/San Remo Live/CC (Dyment/Kabba/Emenike) (Baauer) CC (Rodrigues) 2 29 PINK FEAT. NATE RUESS Just Give Me A Reason RCA USRC11200786 (ARV) 40 IMAGINE DRAGONS It’s Time Interscope USUM71200987 (ARV) (Bhasker) Sony ATV/EMI Blackwood/Pink Inside/Way Above (Pink/Bhasker/Ruess) N (tbc) tbc (tbc) 3 48 JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE Mirrors RCA USRC11300059 (ARV) 41 35 27 RIHANNA Diamonds Def Jam USUM71211793 (ARV) 1# (Timbaland/Timberlake/Harmon) Universal/Warner Chappell/Tennman Tune/Z Tunes/J.Harmon/J.Fauntleroy/Almo (Timberlake/Mosley/Harmon/Godbey/Fauntleroy) (B.Blanco/StarGate) EMI/Kobalt/Matza Ball/Where Da Kasz At (Furler/Eriksen/Hermansen/Levine) 4 33 THE SATURDAYS FEAT. -

Hidden Voices’: an Exploratory Single Case Study Into the Multiple Worlds of a 15 Year Old Young Man with Autism

Title: ‘Hidden voices’: an exploratory single case study into the multiple worlds of a 15 year old young man with autism. Submitted by Stephen O’Leary, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Education (Special Educational Needs) by research in December 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are so many people to whom I own such a debt of gratitude for their ongoing support of my work, not only over the last 4 years, but over the last decade of my involvement in the field of special education. For their ongoing advice and guidance in relation to the technological aspects of my many projects during this time I wish to extend my heartfelt thanks to John Farrell, Peter Deasy and Barry Duncan. For their unrelenting encouragement and support of my work over the years I wish to thank Pat McDonnell, Martin Gleeson, John Fitzgibbons, Claire Droney, Mary Scriven, Tara Vernon, Dennis Burns and Des Hourihane. I further offer my most sincere thanks for the wonderful levels of support I received from my Ed.D supervisors at the University of Exeter; Dr. Hazel Lawson and Dr. Hannah Anglin- Jaffe, as well as to my former supervisor, Dr. -

Cahill Tallies Landslide Victory

GOP Sweeps Ponmouth County SEE STORY BELOW Cloudy, Mild Cloudy and mild with chance FINAL Of rain today, tonight and Red Bub, Freehold again tomorrow. Long Branch (Sea Details, Pjgo 2) I 7 EDITION Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 92 Years VOL. 93, NO. 92 RED BANK, N. J., WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 1969 36 PAGES TEN CEJSTS "UIIIJHIffl Cahill Tallies Landslide Victory NEWARK (AP) — Republi- tered voters, however, has tion, although it fell short of cians preferred to view Ca- can Congressman William T. increased from 139,326 to 193,- 1966 by Republican U.S. Sen. hill's vjctory as evidence the 1HE Cahill has parlayed New Jer- 804 in the interim. Clifford Case. His big win al- public had grown weary of 16 sey voters' desire for an end Meyner was one of only so ' allowed Republicans to years of Democratic rule, to 16 years of Democratic three Democratic gubernato- keep their overwhelming ma- eight of them under Meyner rlile into one of the largest rial candidates to carry Mon- jority in the State Assembly. and eight under Gov. Richard statewide election pluralities mouth in the past 50 years. The voters approved pro- J. Hughes. ever. The others were the present posals for a statewide lottery "It's not any issue," said Cahill rolled into the gover- governor, Richard J. Hughes, and a $271 million water-pol- Republican State Senate Ma- nor's office with overwhelm- and the late A. Harry/Moore. lution bond issue but rejected jority Leader Raymond H. ing pluralities over former The race was widely inter- a measure that would have Bateman of Somerset. -

Writing Through Life

Writing Through Life Poetry and Short Stories Anthology Vol. I, 2020 UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center Writing as Healing Program On Wednesday nights for the past several years UC Davis patients, staff and community members have taken a few hours out of our schedules to write. We sit around a big table (and now on Zoom) and fill pages with our thoughts, our days, our illnesses and traumas. We write about the exquisite beauty of a morning in the garden and the terrible moment of the diagnosis. We each show up with words to give to the page, and we all find the time and space to let them happen. We bring our courage, too, as we share the words and get to be heard, fully, with no questions asked or advice given. Sometimes, as we read, insights and peace move into the space where sorrow and pain held sway. Our pens become tools to release our stories. Our weekly sessions are guided by the work of Pat Schneider, who founded Amherst Writers and Artists, an organization dedicated to a writing method that helps people find their voice by writing in a safe community. We leave critiquing for other writing groups and instead focus on the positive: what we liked, what was strong and what stayed with us in the writing we heard. Pat wanted it that way, so that workshop participants can preserve the writer inside of each of us. Although Pat died August 10, 2020 at the age of 86 years, she left an enduring legacy of groups gathering to write and share and give voice. -

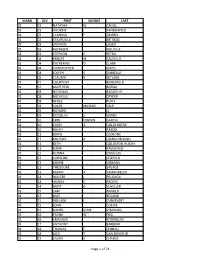

Ward Div First Middle Last 01 01 Natasha W Cahill 01 01 Andrew J Panebianco 01 02 Clarissa F Griebel 01 02 Stavroula Kritikos 01

WARD DIV FIRST MIDDLE LAST 01 01 NATASHA W CAHILL 01 01 ANDREW J PANEBIANCO 01 02 CLARISSA F GRIEBEL 01 02 STAVROULA KRITIKOS 01 03 STEPHEN LAUER 01 03 KATHLEEN MELVILLE 01 03 STEPHON C PETRO 01 04 ERNEST M CALVELLO 01 04 KATHERINE O CLARK 01 04 CHRISTOPHER WEEG 01 04 JOSEPH S ZIMBELLO 01 05 CLAUDIA V SETUBAL 01 07 COURTNEY BIEBERFELD 01 07 MATTHEW BORDA 01 08 NICHOLAS BAGGIO III 01 08 MICHELLE CRYDER 01 08 RENEE RUTH 01 09 CALEB MICHAEL DELP 01 09 RICHARD LI 01 09 DOUGLAS S WONG 01 10 ERIN O BRIEN GARCIA 01 10 LEIGH A GOLDENBERG 01 10 RALPH PASSIO 01 11 DIANE CEDRONE 01 11 MICHAEL A GIANGIORDANO 01 11 BETH GOLDSTEIN HUXEN 01 11 DANA PAVLICHKO 01 12 DONNA DOUGLAS 01 12 CAROLINE LEOPOLD 01 13 JANINE GIBBONS 01 13 THEODORE J SAVAGE 01 13 MARIO A TAMBORELLO 01 14 WALTER J PRUSACKI 01 14 ADAMS E RACKES 01 14 MATT D SCHELLER 01 15 SAM ARNOLD 01 15 MAY BOLAND 01 15 WILLIAM J CHENEVERT 01 15 JOHN COCHIE 01 15 DANIEL JOHN SYMONDS 01 16 FRANK W FRAL 01 16 EMILIANO RODRIGUEZ 01 17 ANTHONY BARBERA 01 18 THOMAS E LEHNAU 01 18 JACK T VAN SKIVER JR 01 19 LAURA A CHANCE Page 1 of 74 WARD DIV FIRST MIDDLE LAST 01 19 KEITH OLKOWSKI 01 19 ROBERT PIRELLO 01 19 SUSAN REILLY 01 20 ROBERT M DEMILIO SR 01 20 THOMAS J RUMBAUGH 01 21 MARGARET ROSE DILLON 01 21 LAURA C KRESCHOLLEK JR 01 21 LAURA C KRESCHOLLEK SR 01 21 THOMAS O NEILL 02 01 BEATRIZ P BORODIAK 02 01 PETER J DECAROLIS 02 01 JOAN DUCKENFIELD 02 01 HONEY A POLIS 02 02 DERMOT B DELUDE DIX 02 02 FERN B LORE 02 02 DOUGLAS J NESMITH 02 02 KEVIN PRICE 02 03 BENJAMIN BLOCK 02 03 ATTIA MARCHAMAN 02 03 ELIZABETH -

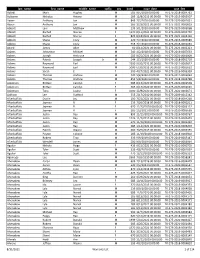

Warrants List August 31, 2021

last_name first_name middle_name suffix sex bond issue_date case_fmt Aafedt Mark Hughes M 585 9/4/2018 00:00:00 TK-275-2018-0004781 Aaltonen Nickolas Antero M 185 12/8/2015 00:00:00 TK-275-2015-0005507 Aasen Anthony Jon M 845 7/7/2020 00:00:00 TK-275-2020-0002631 Aasen Anthony Jon M 285 3/23/2021 00:00:00 TK-275-2021-0000819 Abbott Levi Matthew M 135 9/1/2020 00:00:00 TK-275-2020-0003068 Abbott Rachell Sheree F 1270 8/11/2021 00:00:00 TK-275-2020-0003790 Abbott Rachell Sheree F 825 8/18/2021 00:00:00 TK-275-2021-0002110 Abbott Shane Cody M 220 7/7/2020 00:00:00 TK-275-2016-0006589 Abbott Shane Cody M 955 7/7/2020 00:00:00 TK-275-2018-0001035 Acord James Allen M 60 8/11/2021 00:00:00 TK-275-2021-0002323 Adams Johnathan Michael M 740 4/2/2018 00:00:00 TK-275-2016-0007633 Adams Joseph Ambrose M 585 8/25/2021 00:00:00 TK-275-2021-0003809 Adams Patrick Joseph Jr M 144 1/3/2020 00:00:00 TK-275-2018-0001720 Adams Raymond Earl M 2500 5/30/2013 00:00:00 TK-275-2012-0005622 Adams Raymond Earl M 5000 6/20/2013 00:00:00 TK-275-2012-0005622 Adams Sarah E F 500 4/27/2021 00:00:00 TK-275-2019-0003359 Adams Thomas Andrew M 720 5/8/2020 00:00:00 TK-275-2017-0006063 Adams Thomas Andrew M 855 5/8/2020 00:00:00 TK-275-2018-0003798 Adamson Brittani Carolyn F 585 8/13/2020 00:00:00 TK-275-2020-0002578 Adamson Brittani Carolyn F 385 8/13/2020 00:00:00 TK-275-2020-0002685 Adamson Tana Louise F 1000 12/8/2020 00:00:00 TK-275-2020-0002671 Addison Lee Stafford M 755 2/17/2010 00:00:00 TK-275-2009-0012342 Afterbuffalo Dustin Jay M 100 7/21/2021 00:00:00 TK-275-2018-0004260 -

University of Notre Dame Women's Tennis History & Records

UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME WOMEN'S TENNIS HISTORY & RECORDS UPDATED AS OF JANUARY 5, 2017 ALL-TIME RESULTS Kathy Cordes Sharon Petro Jory Segal Michele Gelfman Jay Louderback 1976 1977-78, ‘80-85 1979 1985-89 1989-present 7-3-1 (.681) 114-45 (.717) 9-1 (.900) 68-40 (.630) 515-233 (.689) First Ranking: 25th, Preseason 1990-91 Seasons in Preseason ITA Rankings: 25 in a row: 1990-91/25th, 1991-92/25th, 1992-93/20th, First Final Ranking: 23rd, 1990-91 1993-94/18th, 1994-95/13th, 1995-96/18th, 1996-97/8th, 1997-98/16th, 1998-99/16th, 1999- 2000/18th, 2000-01/13th, 2001-02/14th, 2002-03/22nd, 2003-04/21st, 2004-05/21st, 2005- Highest Ranking: 2nd (15 times, most recently on Apr. 17, 2007) 06/22nd, 2006-07/4th, 2007-08/9th, 2008-09/17th, 2009-10/6th, 2010-11/4th, 2011-12/20th, Highest Final Ranking: 5th (three times, most recently 2009-10) 2012-13/19th, 2013-14/21st, 2014-15/20th, 2015-16/33rd Highest Preseason Ranking: 4th, 2006-07 Seasons in Final ITA Rankings: 24 in a row: 1990-91/23rd, 1992-93/19th, 1993-94/15th, 1994- Times Ranked Below 30th: 2 (March 26, 2003 – 47th; April 5, 2005 - 31st) 95/28th, 1995-96/6th, 1996-97/21st, 1997-98/19th, 1998-99/15th, 1999-2000/13th, 2000-01/10th, Seasons in ITA Top 25: 24 in a row: 1990-91 – 2013-14 2001-02/23rd, 2002-03/21st, 2003-04/27th; 2004-05/24th, 2005-06/5th, 2006-07/7th, 2007- Seasons in ITA Top 20: 20 in a row: 1992-93 – 2011-12 08/20th, 2008-09/5th, 2009-10/5th, 2010-11/20th, 2011-12/20th, 2012-13/23rd, 2013-14/19th, Seasons in ITA Top 15: 14: 1993-94 – 2002-03, 2005-06 – 2006-07, 2008-09, 2009-10 2014-15/36th, 2015-16/44th Seasons in ITA Top 10: 8: 1995-96, ’96-97, ’98-99, 2000-01, 2005-06 – 2006-07, 2008-09,2009- Most Consecutive Weeks in ITA Rankings: 388 (current), Preseason 1992-93 to final 2015-16 10 Most Consecutive Weeks in ITA Top 25: 125, Preseason 1995-96 to March 12, 2003 Note: The ITA rankings featured 25 teams until they were expanded to 50 teams for the 1992-93 season. -

Cahill Unveils 1.6 Billion State Budget by DAVID M

Chicago 7 Attorneys, Defendants to Be Jailed SEE STORY BELOW Sunny and Cold Sunny and cold today. Clear, colder tonight. Tomorrow THEDAILY FINAL fair and quite cold. Red Bank, Freehold Long Branch EDITION (Bon DitiiU, I'ate 2) I 7 JMonmouih County9* Mom*n Newspaper for 92 Years VOL. 93, NO. 162 UFA) HANK, N. J., MONDAY, FKBHUAKY J6, 1970 26 PAGES 10 CENTS lM Cahill Unveils 1.6 Billion State Budget By DAVID M. GOLDHIMG At a news conference ac- may be changed in future Nevertheless, the budget re- TRENTON (AP) — Gov companying the budget's re- years after the Republi- flects almost $100 million William T. Cahill today pro- lease he said he would pro- can administration reviews more than was appropriated posed a 1970-71 state budget pose new programs^in crime them. Many, he said, were this year for state operations. of almost ifl.fi billion that he fighting, with tlie^emphasis included this year because Most of it will go for in- described as "larger than we on narcotics addiction; high- they had to be. creased money for the State would wish, but smaller than way safety,'and education. "I think this budget reflects Police, the motor vehicle di- the urgent needs of the state The ,budget proposes total in large measure tlie vision, work incentive and re- truly require." expenditures for the fiscal decisions of previous depart- habilitation programs, higher Cahill, New Jersey's first year beginning July 1 of $1,- ment heads and even the pre- education, institutions, and Republican governor in 16 590,118,803, about $300 million vious administration in some state employe salaries and years, included no surprises mote than this year's figure. -

University of Maine System Salaries of Regular Employees the Following Information Includes All Full-Time and Part-Time Employee

University of Maine System Salaries of Regular Employees The following information includes all full-time and part-time employees of the University of Maine System. It is presented by University and then by last name. Employees are shown with their primary title; secondary titles are not included. Salary information is annual base salary for all titles and includes stipends of at least one-year duration. Other earnings such as overtime, overload teaching, and short-term stipends are excluded. It should be noted that not all employees work a full fiscal year but rather work a certain fraction of a full year. Definition of pertinent terms: University: Faculty Appt: UM = University of Maine FY = Fiscal Year 12 months UMA = University of Maine at Augusta AY = Academic Year 9 months UMF = University of Maine at Farmington Federal = Cooperative Extension faculty UMFK = University of Maine at Fort Kent UMM = University of Maine at Machais Bargaining Unit: UMPI = University of Maine at Presque Isle AFUM = Associated Faculties of the Universities of USM = University of Southern Maine Maine SWS = System Wide Services UMPSA = Universities of Maine Professional Staff Association Jobst – Job status: COLT = Associated C.O.L.T. Staff of the Universities of FR = Full-time regular Maine PR = Part-time regular Service and Maintenance = Teamsters Union Local #340, Service and Maintenance FTE - Full-time equivalent = Reflects the fte of all active Unit titles within the employee’s work year. 1.00 FTE = 40 Police = Teamsters Union Local #340, Police Unit hrs/wk. PATFA = The Maine Part Time Faculty Association Non-Represented Salaried . Non-Represented Faculty Law Faculty – Non-Represented Non-Represented Hourly University of Maine System Salaries for Regular Employees by University As of November 25, 2019 CMP Formatted_Name Dept ID Title Salbase JobSt Bargaining Unit Faculty Appt FTE UMA Abbott, Jessica R. -

Masc Summer Workshop Songs--All Schoo

MASC SUMMER WORKSHOP SONGS--ALL SCHOOL APPROPRIATE ABC The Jackson 5 19 Something Mark Wills Absolutely (Story of a Girl) Nine Days Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Adiemus Adiemus & Karl Jenkins Alejandro Lady GaGa All the Small Things Blink-182 And We Danced Hooters Angel Sarah McLachlan Angels Among Us Animal Neon Trees Another Day In Paradise Phil Collins Any Way You Want It Journey Anywhere You go Gin Blossoms Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet Around the World (La la la la La) ATC Austin Powers Back To December Taylor Swift Bad Michael Jackson Bad Day Daniel Powter Bad Day R.E.M. Bad Romance Lady Gaga Basket Case Green Day BBQ Stain Tim McGraw BBQ Stain Tim McGraw Beat It Michael Jackson Beating My Heart Jon McLaughlin Beautiful Day U2 Billy Jean Michael Jackson Black Betty Ram Jam Black Horse & The Cherry Tree (Radio Version) KT Tunstall Black or White Michael Jackson Blame It On The Boogie Jackson 5 Blame It On The Boogie Jackson 5 Blame It On The Boogie EDITED Blow Ke$ha Boom Boom Boom Jock Jams Boom Boom Pow (Clean) Black Eyed Peas Born In The USA Bruce Springsteen Born This Way Lady Gaga Born To Be Alive Patrick Hernandez Born to Hand Jive Grease Boys of Summer DJ Sammy Brand New Day Joshua Radin Break It Off Sean Paul Ft. Rihanna Break Your Heart Taio Cruz Ft. Ludacris Breakaway Kelly Clarkson Breakeven The Script Brighter Than The Sun Colbie Caillat Broadway Goo Goo Dolls Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Bubbly Colbie Caillat Build Me Up Buttercup Temptations California Girls Katy Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jepsen Can't Stop