Case 1:15-Cv-01119 Document 3 Filed 07/14/15 Page 1 of 18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Handbook-English.Docx

Student and Parent Handbook 7480 N. Broadway Bldg. #3, Denver, CO 80221 Office/Attendance Line: (303) 853-1920 Fax: (303) 853-3179 Welcome to Global Intermediate Academy We are happy you are part of our school community! Hours of Operation School Day 8:05 AM – 3:20 PM Office Hours 7:30 AM – 4:00 PM Director AJ Staniszewski 303-853-1921 [email protected] Assistant Director Julianne Hazah 303-853-1922 [email protected] Office Secretary Lupe Quezada 303-853-1920 [email protected] Office Clerk 303-853-1925 Health Assistant Myda Hernandez 303-853-1923 [email protected] Campus Security Steve Reffel 303-853-1927 [email protected] Dear Global Intermediate Academy Families, Welcome to Global Intermediate Academy (GIA). We are an International Baccalaureate (IB) Primary Years Programme (PYP) in 4th and 5th grades and a Middle Years Programme (MYP), in grades 6th – 8th, and we are proud to be one of the elite IB World Schools across Colorado and internationally. The contents of this handbook will provide guidance and support for a safe learning environment. Students and their parents/guardians are encouraged to read the contents of this handbook and discuss them in order to promote understanding and a positive experience for all. We have the highest academic expectations for the students who attend school with us. All staff members are dedicated, caring, and skilled professionals. They help all students achieve by bringing engaging, standards-based learning into the classroom every day. Through our focus on inquiry-based learning, we are creating the next generation of strong, internationally minded leaders in our community. -

Jodi Gersh Managing Director Development Director Owner/Operator SVP, Audience and Platforms Public Media Company WMUK Conan Venus and Colorado Public Radio Company

Does your community know that you exist? Grow station audience and revenue via increased awareness May 19, 2021 3 pm ET/2 p.m. CT/1 p.m. MT/12 noon PT A Public Media Company Forum | www.publicmedia.co LOGISTICS All attendees are Please use the chat function Please use chat or contact muted by default for questions & comments Steve Holmes for tech support: [email protected] Located at the bottom of the screen Click to open up chat box and ask questions or make comments 2 ABOUT PUBLIC MEDIA COMPANY Public Media Company is a nonprofit consulting firm dedicated to serving public media. We leverage our business expertise to increase public media’s impact across the country. Public Media Company works in partnership with stations in urban and rural communities to find innovative solutions and grow local impact. We have worked with over 300 radio and TV stations in all 50 states www.publicmedia.co 3 AGENDA Why Awareness building matters WMUK Colorado Public Radio Q&A 4 WHY AWARENESS? The more people are aware of your existence as a local media outlet, the more likely they will engage directly with your offerings: • Tuning in over the air • Typing it into the search bar • Listening to a podcast • Visiting your website proactively 5 HOW TO MEASURE AWARENESS First: Ask for un-aided recall “What local television stations do you watch?” “What radio stations do you listen to?” “Where do you go for news?" Second: Ask for aided recall “Which of the following services do you turn to for…” List well-known media in town (newspapers, radio, TV, sites, -

Celestial Seasonings® B Strong Ride Donates Proceeds from 7Th Annual Cycling Fundraiser

Celestial Seasonings® B Strong Ride Donates Proceeds From 7th Annual Cycling Fundraiser February 22, 2018 $205,000 to Boulder Community Health Center for Integrative Care, George Karl Foundation and Camp Kesem - University of Colorado BOULDER, Colo., Feb. 22, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- B Strong Ride cycling event has donated $150,000 to the Boulder Community Health Center for Integrative Care, $35,000 to the George Karl Foundation, and $20,000 to Camp Kesem at the University of Colorado. The donations were made February 21, 2018 during a special event at Celestial Seasonings, Inc., title sponsor of B Strong Ride. The funds were raised at the annual B Strong Ride event through corporate sponsorship, rider registration fees and contributions in support of individual riders. "Supporting these great organizations is consistent with Celestial Seasonings long-standing mission to help people live healthier and happier lives," said Tim Collins, Celestial Seasonings Vice President of Marketing and presenter of the check for $150,000 from B Strong Ride to Boulder Community Health Center for Integrative Care. "We're honored by the opportunity to play an active role in our local community and help Boulder-area cancer patients and survivors through our continued title sponsorship of B Strong Ride. We're already gearing up for the 2018 ride in August." The Boulder Community Health Center for Integrative Care provides a wide range of services to cancer patients including acupuncture, manual lymph drainage, reflexology, massage therapy, Reiki and Healing Touch Massage, and wellness and integrative care consultation. The services enhance wound healing, shorten hospital stays, and reduce pain medication needs. -

2021-KOSI-Imperfect-Foods-Rules

The following promotion is intended for participants in the United States only, and will be governed by United States laws. Do not proceed in this promotion if you are not eligible or not currently located in the United States. Further eligibility restrictions are contained in the official rules below. 2021 KOSI 101.1 Fill Your Fridge With Imperfect Foods Giveaway OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE OR PAYMENT WILL NOT INCREASE ENTRANT’S CHANCE OF WINNING. Promotion Administrator: KOSI-FM, 7800 East Orchard Road, Suite 400, Greenwood Village, CO 80111 Promotion Sponsor: Impact Marketing and Promotions, P.O. Box 267907, Weston, FL 33326. 1. HOW TO ENTER a. These rules govern the 2021 KOSI 101.1 Fill Your Fridge With Imperfect Foods Giveaway (the “Contest”) being conducted by KOSI-FM (the “Station”). The Contest will begin at 9:00am Mountain Time (“MT”) on March 29, 2021 and will end on April 12, 2021 at approximately 10:00 a.m. (“Contest Period”). b. To participate in the Contest, visit www.kosi101.com/imperfect between 9:00am MT on March 29, 2021 and April 11, 2021 at 11:59pm MT (“Entry Period”) and follow the links and instructions to enter the Contest and submit your first name and last name, zip code, telephone number, date of birth, gender and a valid email address. An Entrant may use only one (1) email address for purposes of entry in this Contest. Internet entries will be deemed made by the authorized account holder of the email address submitted at the time of entry. -

Grand County Council Regular Meeting

GRAND COUNTY COUNCIL REGULAR MEETING Grand County Council Chambers 125 East Center Street, Moab, Utah AGENDA Tuesday, March 18, 2014 4:00 p.m. Call to Order Pledge of Allegiance Approval of Minutes (Diana Carroll, Clerk/Auditor) A. February 21, 2014 (County Council Special Meeting: Workshop on Policies and Procedures of the Governing Body), Postponed from March 4, 2014 B. March 4, 2014 (County Council Meeting) C. March 14, 2014 (County Council Special Meeting: Capital Facilities Workshop) Ratification of Payment of Bills Elected Official Reports Council Administrator Report Department Head Reports D. 2013 Annual Review of Moab Uranium Mill Tailings Remedial Action (UMTRA) Project (Lee Shenton, Moab UMTRA Liaison) Agency Reports E. 2013 Honey Bee Inspection Report (Jerry Shue, Grand County Honey Bee Inspector) Citizens to Be Heard Presentations F. Introduction of John Foster, Director, Museum of Moab, Postponed from March 4, 2014 (Dave Vaughn and Don Montoya, President, Museum of Moab Board) G. Presentation of 2014 Utah Weed Control Association Biological Award to Wright Robinson (Tim Higgs, Grand County Weed Supervisor and Council Member Paxman) H. Presentation of 2014 Nash Wash Wildlife Management Area Habitat Management Plan (Makeda Hanson, Impact Analysis Biologist, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources) I. Presentation on Community Letters Regarding Congressman Bishop Public Lands Initiative (Susan Roche, Deb Walter, Bob O’Brian and Bill Rau, Citizens) Discussion Items J. Discussion on Funding of Proposed Full Time Lead Technician Position for the Weed Department (Ruth Dillon, Council Administrator, Orlinda Robertson, Human Resources Director, and Tim Higgs, Weed Supervisor) K. Calendar Items and Public Notices (KaLeigh Welch, Council Office Coordinator) General Business- Action Items- Discussion and Consideration of: L. -

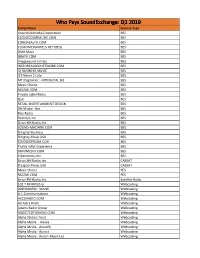

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

Curriculum Vitae

Paula E. Cushing, Ph.D. Senior Curator of Invertebrate Zoology, Department of Zoology, Denver Museum of Nature & Science, 2001 Denver,Colorado 80205 USA E-mail: [email protected]; Web: https://science.dmns.org/museum- scientists/paula-cushing/, http://www.solifugae.info, http://spiders.dmns.org/default.aspx; Office Phone: (303) 370-6442; Lab Phone: (303) 370-7223; Fax: (303) 331-6492 CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 1990 - 1995, Ph.D. Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, 1985 - 1988, M.Sc. Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, 1982 - 1985, B.Sc. PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS AND POSITIONS Denver Museum of Nature & Science, Senior Curator of Invertebrate Zoology, 1998 - present Associate Professor Adjoint, Department of Integrative Biology, University of Colorado, Denver, 2013 - present Denver Museum of Nature & Science, Department Chair of Zoology, 2006 – 2011 Adjunct Faculty, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Colorado, Boulder, 2011 - present Affiliate Faculty Member, Department of Biology and Wildlife, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, 2009 – 2012 Adjunct Faculty, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management, Colorado State University, 1999 – present Affiliate Faculty Member, Department of Life, Earth, and Environmental Science, West Texas AMU, 2011 - present American Museum of Natural History, Research Collaborator (Co-PI with Lorenzo Prendini), 2007 – 2012 College of Wooster, Wooster, Ohio, Visiting Assistant Professor, 1996 – 1997 University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, Postdoctoral Teaching Associate, 1996 Division of Plant Industry, Gainesville, Florida, Curatorial Assistant for the Florida Arthropod Collection, 1991 National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian), high school intern at the Insect Zoo, 1981; volunteer, 1982 GRANTS AND AWARDS 2018 - 2022: NSF Collaborative Research: ARTS: North American camel spiders (Arachnida, Solifugae, Eremobatidae): systematic revision and biogeography of an understudied taxon. -

Michael Gifford Has Been on the Radio in Denver for 20 Years, Including 13 Years at Hot AC MIX 100 in Afternoon Drive and As Music Director and Assistant PD

AM Drive (6am – 11am ET) Michael Gifford has been on the radio in Denver for 20 years, including 13 years at Hot AC MIX 100 in afternoon drive and as music director and assistant PD. He also hosted mornings on Oldies KOOL 105 and spent five years at Jones Radio Networks as morning personality on "Good Time Oldies". Giff loves radio and the listeners. Building relationships with the people that tune in everyday is what it is all about for Giff. Midday (11am – 4pm ET) Dave Hunter ’s career includes lots of Denver radio…two stints at the legendary KIMN in Denver, afternoon drive at KS-104 (KQKS), evenings at Y-108 (KRXY), and mornings on Dial Global Hot AC format in the mid-nineties. Dave programmed the Hot AC format at Waitt Radio Networks before returning to DG to do middays on AC. PM Drive (4pm – 9pm ET) Scott Curtis joined Jones Radio Networks in 1993 and has been the afternoon guy on AC since 1997. Prior to JRN, Scott played the hits on the legendary KXL-FM in Portland, OR, and handled various formats in the Denver area, from AC on KHOW, CHR on Y-108, Rockin’ the Rockies on KBPI, and hosting the evening love songs on KOSI. Evenings (9pm – 2am ET) Jenny D is a Colorado native with a degree in Technical Journalism from Colorado State University. Recognizing and embracing her natural giftings for broadcasting, she interned for Denver's number one Country station KYGO, becoming a promotions Ninja, Assistant Producer for the morning show, all around utility person for the station, and ultimately, part of the air staff. -

2010 Radio Winners

2010 RADIO AWARD WINNERS Category Title of Program 2nd Place Title of Program SMALL & MEDIUM MARKET R-1 Best Public Service Announcement KRAI-FM Sound of Music Kat KSMT-FM Bear Aware R-2 Best Community Service Campaign KZMV-FM Scholarship Program KSMT-FM Community Connection Scholarship R-3 Best Station Sponsored Community Event KRAI-FM KRAI 12th Annual Holiday Drive KSRX-FM Recycling Round Up R-4 Best Public Affairs Program KPMX-FM KPMX Coffee Break "Pastor Doug" KPMX-FM KPMX Coffee Break "Sterling Public Library" R-5 Best Regularly Scheduled Newscast KSMT-FM KSMT 4pm News with Michael Klepper KPMX-FM Noon News with Chris Brom R-6 Best News Feature Report or Series KAJX-FM Secure Communities with Kristina Tabor KWSB-FM Dr. Vandenbusche Interview with Trevor Mark 1 Year Anniversary of MPD Shooting - Janine R-7 Best Single Event News Coverage KKXK-FM Mayfield KSPN-FM X Games 15 Preview - Rochelle Obechina R-8 Best On Air Contest for a Station KSPN-FM The Great Holiday Giveaway KATR-FM Kat - Country Full Throttle Tour R-9 Best On Air Promotional Campaign KSMT-FM What You Want to Hear Wednesday KZMV-FM Your Voice R-10 Best Image Marketing Campaign for a Station R-11 Best Morning Show KSKE-FM BT in the Morning KPMX-FM KPMX Morning Circus "Cruise Liner" with Andy Rice R-12 Best Midday Show KZMV-FM Midday with Dominic KPMX-FM Middays with Janice "Coats for Kids" The KPMX Afternoon Escape "Time to Go Home" R-13 Best Afternoon Show KSMT-FM Afternoons with Stacy KPMX-FM with Chris "Bull" Brom R-14 Best Evening Show KFMU-FM Pickin' with PMAC - -

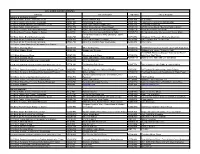

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

EEO Public File Report

EEO Public File Report Employment Unit Covered: KYGO-FM, KOSI(FM), KKFN(FM) & KEPN(AM) REPORTING PERIOD: 12/01/2019-11/30/2020 Full Time Vacancies Filled During Reporting Period and Recruitment/Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Vacancy Job Title Date Hire Source Recruitment Advertising Filled Source Area Director of Marketing 12/05/2019 All Access See Recruitment Radio and Promotions Source List Radio Corporate Traffic 12/18/2019 Indeed See Recruitment Radio Team Source List Accounts Receivable 03/30/2020 Indeed See Recruitment Radio Clerk Source List Accounts Receivable 10/21/2020 Indeed See Recruitment Radio Clerk Source List Total Number of Interviewees For All Full-Time Vacancies Filled During Reporting Period Per Recruitment/Referral Sources: Recruitment Source Number of Interviewees Referred All Access 1 Connection in the company 1 Current Worker 1 Glassdoor 1 Indeed 17 Market Referral 4 Work in Sports 1 Total 26 PERFORMANCE INITIATIVES UNDERTAKEN 12/01/2019 – 11/30/2020 During the reporting period, the Unit participated in a company-wide mentorship program. The mentoring program enables participants an opportunity to develop professional relationships, skills and attributes that will help them progress in their career. Several staff members participated either as a mentor or mentee. The duration of the mentorship lasted 6 months. The Unit also created an internal leadership development program called LEAD for three (3) chosen employees to shadow departments throughout our building to further gain leadership and industry experience. LEAD was slated to begin on April 1, 2020, however due to the shift in remote workforce on March 13, 2020, the LEAD program was cancelled. -

Colorado News Connection

COLORADO NEWS 18. KRSJ-FM, KIQX-FM (2) Durango 20 28 29 44 45 31 19 19. KEZZ-AM (1) Fort Collins 21 22 23 39 20. KPAW-FM, KCOL-AM (2) Fort Collins 36 21. KUNC-FM (1) Fort Collins 24 747 13 6 22. KFTM-AM, KBRU-FM (2) 3 14 Fort Morgan 26 25 4 15 16 17 23. Metro Networks-Fort Morgan ONNECTION 27 5 8 C (1) Fort Morgan 9 10 24. KMTS-FM, KGLN-AM (2) 12 30 Glenwood Springs 38 41 25. KEKB-FM, KBKL-FM (2) Grand Junction 42 43 34 46 33 26. KNZZ-AM, KMGJ-FM, KMOZ-FM, KTMM-AM, KJYE-FM (5) 37 35 12 Grand Junction 11 18 40 27. KZKS-FM, KAYW-FM, KWGL-FM, KAVP-AM, KRVG-FM (5) 32 Grand Junction 28. KSME-FM, KIIX-AM (2) Greeley 123 state/regional radio stations aired CNC stories in 2005 29. Metro Networks-Greeley (1) Greeley 30. KVLE-FM (1) Gunnison 1. KRZA-FM (1) Alamosa 31. KRMR-FM, KFMU-FM (2) Hayden 2. KGIW-AM, KALQ-FM (2) Alamosa CNC Market Share Information 32. KUTE-FM, KSUT-FM (2) Ignacio 3. KAJX-FM, KPVW-FM (2) Aspen 33. KBLJ-AM, KTHN-FM (2) La Junta 4. Metro Networks-Aspen (1) Denver-Boulder 28% 34. KLMR-AM, KSNZ-FM (2) Lamar 35. KVAY-FM (1) Lamar Aspen Colorado Springs 21% 5. KNFO-FM, KSPN-FM, KKCH-FM, 36. KJCD-FM, KKFN-AM, KYGO-FM (3) Longmont KTUN-FM, KSKE-AM (5) Aspen/ Pueblo 23% 37. KSLV-AM, KSLV-FM (2) Monte Vista Glenwood Springs Grand Juncion 32% 38.