Horace Newcomb in Conversation with Tara Mcpherson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement for the Library of Congress Study on the Current State Of

Library of Congress Study on the Current State of Recorded Sound Preservation and Restoration Statement by Margaret A. Compton, Film, Videotape, & Audiotape Archivist Ruta Abolins, Director The Walter J. Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards Collection University of Georgia Libraries, Athens, Georgia The University of Georgia Library preserves a substantial amount of archival audio material of all formats in both the Peabody Awards Archives and the Walter J. Brown Media Archives. The Peabody Award is one of the most respected and coveted awards in broadcasting. It was conceived in 1939 by Lambdin Kay, manager of WSB Radio in Atlanta, and sponsored by John E. Drewry, dean of the Grady School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia. The first awards were given in 1940 for radio broadcasts of 1939. Television entries began in 1949. Just this year, over 1,100 audio and visual entries were received at the awards office, totaling approximately 5,000 physical documents which will be added to the archives after judging is complete. The Peabody Awards Archives is administrated by the University of Georgia library and is housed in the Main Library on campus. This archives is important for studying the history of broadcasting, since every entry submitted—not just those which win Peabody Awards—has been kept, along with any paper material and ephemera submitted with the programs, preserving a snapshot of the best in annual broadcasting from around the world. The Library’s Walter J. Brown Media Archives is made up of a broader range of campus, local, and southeast regional archival audio and visual materials. -

The Digital Dilemma 2 Perspectives from Independent Filmmakers, Documentarians and Nonprofi T Audiovisual Archives

Copyright ©2012 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. “Oscar,” “Academy Award,” and the Oscar statuette are registered trademarks, and the Oscar statuette the copyrighted property, of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The accuracy, completeness, and adequacy of the content herein are not guaranteed, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences expressly disclaims all warranties, including warranties of merchantability, fi tness for a particular purpose and non-infringement. Any legal information contained herein is not legal advice, and is not a substitute for advice of an attorney. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this document may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Inquiries should be addressed to: Science and Technology Council Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences 1313 Vine Street, Hollywood, CA 90028 (310) 247-3000 http://www.oscars.org Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Digital Dilemma 2 Perspectives from Independent Filmmakers, Documentarians and Nonprofi t Audiovisual Archives 1. Digital preservation – Case Studies. 2. Film Archives – Technological Innovations 3. Independent Filmmakers 4. Documentary Films 5. Audiovisual I. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and -

2006 Promax/Bda Conference Celebrates

2006 PROMAX/BDA CONFERENCE ENRICHES LINEUP WITH FOUR NEW INFLUENTIAL SPEAKERS “Hardball” Host Chris Matthews, “60 Minutes” and CBS News Correspondent Mike Wallace, “Ice Age: The Meltdown” Director Carlos Saldanha and Multi-Dimensional Creative Artist Peter Max Los Angeles, CA – May 9, 2006 – Promax/BDA has announced the addition of four new fascinating industry icons as speakers for its annual New York conference (June 20-22, 2006). Joining the 2006 roster will be host of MSNBC’s “Hardball with Chris Matthews,” Chris Matthews; “60 Minutes” and CBS News correspondent Mike Wallace; director of the current box-office hit “Ice Age: The Meltdown,” Carlos Saldanha, and famed multi- dimensional artist Peter Max. Each of these exceptional individuals will play a special role in furthering the associations’ charge to motivate, inspire and invigorate the creative juices of members. The four newly added speakers join the Promax/BDA’s previously announced keynotes, including author and social activist Dr. Maya Angelou; AOL Broadband's Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Kevin Conroy; Fox Television Stations' President of Station Operations Dennis Swanson; and CNN anchor Anderson Cooper. For a complete list of participants, as well as the 2006 Promax/BDA Conference agenda, visit www.promaxbda.tv. “At every Promax/BDA Conference, we look to secure speakers who are uniquely qualified to enlighten our members with their valuable insights," said Jim Chabin, Promax/BDA President and Chief Executive Officer, in making the announcement. “These four individuals—with their diverse, yet powerful credentials—will undoubtedly shed some invaluable wisdom at the podium.” This year’s Promax/BDA Conference will be held June 20-22 at the New York Marriott Marquis in Times Square and will include a profusion of stimulating seminars, workshops and hands-on demonstrations all designed to enlighten, empower and elevate the professional standings of its members. -

OPC, Coalition Sign Pact to Boost Freelancer Safety

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • February 2015 OPC, Coalition Sign Pact to Boost Freelancer Safety By Emma Daly and the freelancers who Diane Foley, mother of the late are assuming an ever- freelance reporter James Foley, was greater burden in cover- guest of honor at a panel discussion ing dangerous stories, to launch “A Call for Global Safety the panelists see these Principles and Practices,” the first principles as a first step industry code of conduct to include toward greater responsi- media companies and freelancers bility and accountability in an attempt to reduce the risks to by both reporters on the those covering hazardous stories. ground and their editors. The guidelines were presented to an “I am deeply proud Rhon G. Flatts audience of journalists and students of the OPC and the OPC David Rohde of Reuters, left, and Marcus Mabry during two panel discussions held at Foundation’s part in this speak to students and media about a the Columbia University School of long overdue effort,” new industry code of conduct. Journalism’s Stabile Student Center Mabry said. Shehda Abu Afash in Gaza. on Feb. 12 and introduced by Dean Sennott flagged the horrific mur- By the launch on Thursday al- Steve Coll. der of Jim Foley as a crucial moment most 30 news and journalism orga- The first panel – David Rohde in focusing all our minds on the need nizations had signed on to the prin- of Reuters, OPC President Marcus to improve safety standards, despite ciples, including the OPC and OPC Mabry, Vaughan Smith of the Front- efforts over the past couple of de- Foundation, AFP, the AP, the BBC, line Freelance Register, John Dan- cades to introduce hostile environ- Global Post Guardian News and Me- iszewiski from the AP and Charlie ment and medical training, as well dia, PBS FRONTLINE and Thom- Sennott of the Ground Truth Project as protective equipment and more af- son Reuters. -

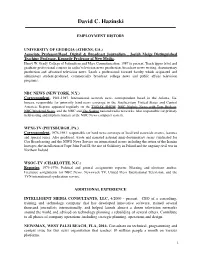

David C. Hazinski

David C. Hazinski EMPLOYMENT HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA (ATHENS, GA.) Associate Professor/Head, Digital & Broadcast Journalism , Josiah Meigs Distinguished Teaching Professor, Kennedy Professor of New Media. Henry W. Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication. 1987 to present. Teach upper level and graduate professional courses in radio/ television news production, broadcast news writing, documentary production and advanced television news. Leads a professional focused faculty which originated and administers student-produced, commercially broadcast college news and public affairs television programs. NBC NEWS (NEW YORK, N.Y.) Correspondent, 1981-1987. International network news correspondent based in the Atlanta, Ga. bureau, responsible for primarily hard news coverage in the Southeastern United States and Central America. Reports appeared regularly on the TODAY SHOW, NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw, NBC Weekend News, and the NBC and The Source national radio networks. Also responsible for primary field-testing and implementation of the NBC News computer system. WPXI-TV (PITTSBURGH, PA.) Correspondent, 1976-1981. responsible for hard news coverage of local and statewide events, features and special series. Also produced, wrote and narrated national mini-documentary series syndicated for Cox Broadcasting and the NIWS News Service on international issues including the return of the Iranian hostages, the installation of Pope John Paul II, the rise of Solidarity in Poland and the ongoing civil war in Northern Ireland. WSOC-TV (CHARLOTTE, N.C.) Reporter, 1973-1976. Political and general assignments reporter. Morning and elections anchor. Freelance assignments for NBC News, Newsweek TV, United Press International Television, and the TVN international syndication service. ADDITIONAL EXPERIENCE INTELLIGENT MEDIA CONSULTANTS, LLC, 4/2000 - present. -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 in the Matter of Future of Media and Information Needs Of

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of Future of Media and Information Needs GN Docket No. 10-25 of Communities in a Digital Age COMMENTS OF BELO CORP. Belo Corp. (“Belo” or “the Company”)1 hereby submits its Comments in response to the FCC’s Public Notice released on January 21, 2010 in the above-referenced proceeding, in order to assist the Commission in its assessment of Americans’ access to vibrant, diverse sources of news and information. As discussed in more detail below, Americans have access to a vast amount of diverse news and information content, thanks in no small part to the public service provided by Belo and other broadcasters. Moreover, although digital television is still in its infancy, it already has allowed Belo and other television broadcasters to implement innovative new services and pursue new opportunities to better serve their audiences. Television operators surely will continue to explore new ways to use DTV technology to enhance their roles as public servants. Most importantly, the Commission should recognize that Belo, like many other broadcasters, 1 Belo is one of the nation’s largest pure-play, publicly-traded television companies. It owns and operates 20 television stations, reaching more than 14 percent of U.S. television households in 15 markets. Belo stations consistently deliver distinguished journalism for which they have received significant industry recognition including 12 Alfred I. duPont- Columbia University Silver Baton Awards; 11 George Foster Peabody Awards; and 26 national Edward R. Murrow Awards – all since 2000, and in each case more than any other commercial station group in the nation. -

The Professional Journal of the Youth Media Field

The Professional Journal of the Youth Media Field ~ . Connecting People > Creating Change Acknowledgements We would like to thank both Anna Lefer and Erlin Ebreck at Open Society Institute for selecting the Academy for Educational Development as the new home for Youth Media Reporter providing funds for us to make this first printed volume available at no cost to educators, academics and leading media professionals. Additionally, the first YMR Peer Review Board was instrumental in this publication, particularly writing and acting as readers for the “special features” articles. Thanks to Sam Chaltain, Tim Dorsey, Renee Hobbs, Anna Kelly, Ibrahim Abdul Matin, Meghan McDermott, Katina Paron, Anindita Dutta Roy, and Irene Tostado. Thanks to additional special features contributors Dare Dukes, Steven Goodman, Christine Mendoza, Dan O’Reilly-Rowe, Sumitra Rajkumar, Erin Reilly, Rebecca Renard, Alice Robison, Elisabeth Soep, and Kathleen Tyner. Many thanks to the individuals who supported the editorial process of this journal Jessica Bynoe, Elayne Archer and Ali McCart. Special thanks to Stephen Hindman, the designer, who has given YMR a new look and innovative feel. Finally, and most importantly, thank you to all of the contributors and readers of YMR throughout the year. We hope you continue reading this publication and we look forward to the ideas and information you will offer for future articles. ©2008 Academy for Educational Development 100 Fifth Avenue, 8th Floor, New York NY 10011 Youth Media Reporter 2007 Issue 1 • January 43. The Field is Bigger than We Think 1. MySpace & YouTube: Corporate-Owned Spaces Ingrid Hu Dahl for Youth Activism? Ingrid Hu Dahl 46. -

Children's Television. Hearing on H.R. 1677 Before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance of the Committee on Energy and Commerce

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 315 048 IR 014 159 TITLE Children's Television. Hearing on H.R. 1677 before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance of the Committee on Energy and Commerce. House of Representatives, One Hundred First Congress, First Session. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Energy and Commerce. PUB DATE 6 Apr 89 NOTE 213p.; Serial No. 101-32. AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Mat.. als (090) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childrens Television; *Federal Legislation; Hearings; *Programing (Broadcast); *Television Commercials IDENTIFIERS Congress 101st ABSTRACT A statement by the chairman of the subcommittee, Representative Edward J. Markey opened this hearing on H.R. 1677, the Children's Television Act of 1989, a bill which would require the Federal Communications Commission to reinstate restrictions on advertising during children's television, to enforce the obligation of broadcasters to meet the eduCational and informational needs of the child audience, and for other purposes. The text of the bill is then presented, followed by related literature, surveys, and the testimony of nine witnesses: (1) Daniel R. Anderson, Psychology Department, University of Massachusetts; (2) Helen L. Boehm, vice president, Children's Advertising Review Unit, Council of Better Business Bureaus, Inc.;(3) Honorable Terry L. Bruce, Representative in Congress from the State of Illinois;(4) William P. Castleman, vice president, ACT III Broadcasting, on behalf of the Association of Independent Television Stations;(5) Peggy Charren, president, Action for Children's Television; (6) DeWitt F. -

Janis-Press Notes 10 26 15

JANIS: LITTLE GIRL BLUE Written and Directed by Amy J. Berg FilmRise NY Publicity LA Publicity Digital Publicity 34 35th Street Donna Daniels David Magdael Lee Meltzer Brooklyn, NY 11232 [email protected] dmagdael@tcdm- [email protected] 718.369.9090 et associates.com 212.373.6142 [email protected] 347.694.4650 213.624.7827 www.filmrise.com **** Official Selection 2015 Venice Film Festival 2015 Toronto International Film Festival 2015 DOC NYC 2015 BFI London Film Festival 2015 International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam **** PBS and Content Media Corporation Present A FilmRise Release A Production of Disarming Films, Jigsaw Productions and THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC’s American Masters In association with Sony Music Entertainment and Union Entertainment Group Written and Directed by Amy J. Berg Narrated by Chan Marshall Produced by Alex Gibney Produced by Amy J. Berg Jeffrey Jampol Katherine LeBlond Running Time: 105 Minutes TAGLINE Oscar-nominated documentarian Amy Berg examines the meteoric rise and untimely fall of one of the most revered and iconic rock ‘n’ roll singers of all time: Janis Joplin. Joplin’s life story is Oscar-nominated documentarian Amy Berg examines the meteoric rise and untimely fall of one of the most revered and iconic rock ‘n’ roll singers of all time: Janis Joplin. Joplin’s life story is revealed for the first time on film through electrifying archival footage, revealing interviews with friends and family and rare personal letters, presenting an intimate and insightful portrait of a bright, complicated artist who changed music forever. SYNOPSIS Janis Joplin is one of the most revered and iconic rock and roll singers of all time, a tragic and misunderstood figure who thrilled millions of listeners and blazed new creative trails before her death in 1970 at age 27. -

AM Johnny Carson Production Bios FINAL Rev040412

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: pbs.org/pressroom or thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: pbs.org/americanmasters & facebook.com/americanmasters American Masters Johnny Carson: King of Late Night Premieres nationally Monday, May 14 at 9 p.m. (ET) on PBS (check local listings) Production Biographies Peter Jones Writer , Director and Producer Two-time Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Peter Jones began his career as a broadcast journalist. A graduate of Stanford University with a Master’s Degree in Journalism from Northwestern, Jones served as an assignment editor, feature reporter and news anchor at television stations across the country, winning numerous honors from United Press International and The Associated Press. In 1987, he formed Peter Jones Productions (PJP), originally focusing on documentaries related to the history of the Hollywood film industry. The company produced 85 profiles for the A&E series Biography over a 10-year period. Jones became well-known for securing previously unattainable rights without relinquishing editorial control, including those for such subjects as Charlie Chaplin, Dr. Seuss and Georgia O’Keeffe. Music artists were a specialty. In addition to features on Sam Phillips, Brian Wilson and Nat King Cole, PJP produced a week of profiles on musical talent from the famed Brill Building, culminating in a two-hour special entitled Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music . Jones wrote and directed a two-hour Biography special on Judy Garland that won a 1997 Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Informational Series, the first for the network. His two-hour special Ozzie and Harriet: The Adventures of America’s Favorite Family became the highest-rated documentary in the network’s history, earning a 1999 Primetime Emmy Award nomination for Outstanding Nonfiction Series. -

2014 Brochure (PDF)

About the SOPA Awards for Editorial Excellence The SOPA Awards for Editorial Excellence were established in 1999 as a tribute to editorial excellence in both traditional and new media, and were designed to encourage editorial vitality throughout the region. The awards cover a broad range of categories reflecting Asia’s diverse geo-political environment and vibrant editorial scene. Central to the SOPA Awards’ ongoing success is the high caliber of international judges who preside over the award entries. The SOPA Awards have consistently secured judges from many of the region’s leading newspapers as well as consumer and trade magazines and academics from prestigious universities – a reflection of the stature of the awards. Judges ensure that entries are analyzed and selected according to a demanding set of criteria. The SOPA Awards are coordinated by a committee of publishing professionals from the business and editorial sectors. These dedicated individuals volunteer their time throughout the year to ensure the awards’ rules, judges, entries; event, sponsorships and promotions all come together smoothly. The SOPA Awards set a valuable benchmark for the industry, and have become news items in their own right, generating media coverage and attention not only across the Asia-Pacific region, but also on the global arena. Corporate Support Sponsorship is key to ensuring the Award’s growth, and over the past years, SOPA has been fortunate in receiving strong, continuous support from its partners. As the Awards have grown, so too has the interest from corporations, and this year, we look again to the generosity of sponsors to help us deliver the best Awards we can. -

Georgia Judges, Journalists and Lawyers and the First Amendment a Primer on Recurring and Emerging Issues and the Law

29TH ANNUAL GEORGIA BAR MEDIA & JUDICIARY CONFERENCE FEBRUARY 28, 2020 STATE BAR HEADQUARTERS / ATLANTA, GEORGIA Georgia Judges, Journalists and Lawyers And the First Amendment A Primer on Recurring and Emerging Issues and the Law Sponsors: CNN ACLU of Georgia Daily Report American Constitution Society, Georgia First Amendment Foundation Georgia Chapter Greenberg Traurig LLP Atlanta Journal-Constitution Jones Day Atlanta Press Club Judicial Council / Administrative Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP Office of the Courts Caplan Cobb LLP Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP Council of Probate Court Judges State Bar of Georgia Council of State Court Judges Taylor English Duma LLP Council of Superior Court Judges Planning Committee: Peter Canfield, Jones Day, Chair David Armstrong, Georgia News Lab Frank LoMonte, The Brechner Center Hon. Anne Elizabeth Barnes, Georgia Court of Hon. Hollie Manheimer, Magistrate Judge, DeKalb Appeals County Ed Bean, Poston Communications LLC John McCosh, Georgia Recorder Sarah Brewerton-Palmer, Caplan Cobb LLP Shawn McIntosh, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution Kathy Brister, KB Media Amber Philogene, Jones Day Michael Caplan, Caplan Cobb LLP Don Plummer, Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta Tom Clyde, Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP Hyde Post, Hyde Post Communications Sarah Coole, State Bar of Georgia Jonathan Ringel, Daily Report Cynthia Counts, Duane Morris LLP Eric Schroeder, Bryan Cave LLP Jennifer Davis Ward, Georgia Defense Lawyers Drew Shenkman, CNN Assoc. Hon. Rucker Smith, Chief Judge, Southwestern Hon. Susan Edlein, Fulton Co. State Court Jud. Cir. Ken Foskett, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution Ashley Stollar, State Bar of Georgia Lesli Gaither, Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP Ron Thomas, Morehouse College Richard T. Griffiths, Georgia First Amendment Hon.