Ceremonial Textiles of the Mardi Gras Indians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neil Foster Carries on Hating Keith Listens To

April 2017 April 96 In association with "AMERICAN MUSIC MAGAZINE" ALL ARTICLES/IMAGES ARE COPYRIGHT OF THEIR RESPECTIVE AUTHORS. FOR REPRODUCTION, PLEASE CONTACT ALAN LLOYD VIA TFTW.ORG.UK Chuck Berry, Capital Radio Jazzfest, Alexandra Palace, London, 21-07-79, © Paul Harris Neil Foster carries on hating Keith listens to John Broven The Frogman's Surprise Birthday Party We “borrow” more stuff from Nick Cobban Soul Kitchen, Jazz Junction, Blues Rambling And more.... 1 2 An unidentified man spotted by Bill Haynes stuffing a pie into his face outside Wilton’s Music Hall mumbles: “ HOLD THE THIRD PAGE! ” Hi Gang, Trust you are all well and as fluffy as little bunnies for our spring edition of Tales From The Woods Magazine. WOW, what a night!! I'm talking about Sunday 19th March at Soho's Spice Of Life venue. Charlie Gracie and the TFTW Band put on a show to remember, Yes, another triumph for us, just take a look at the photo of Charlie on stage at the Spice, you can see he was having a ball, enjoying the appreciation of the audience as much as they were enjoying him. You can read a review elsewhere within these pages, so I won’t labour the point here, except to offer gratitude to Charlie and the Tales From The Woods Band for making the evening so special, in no small part made possible by David the excellent sound engineer whom we request by name for our shows. As many of you have experienced at Rock’n’Roll shows, many a potentially brilliant set has been ruined by poor © Paul Harris sound, or literally having little idea how to sound up a vintage Rock’n’Roll gig. -

From Maroons to Mardi Gras

FROM MAROONS TO MARDI GRAS: THE ROLE OF AFRICAN CULTURAL RETENTION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE BLACK INDIAN CULTURE OF NEW ORLEANS A MASTERS THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF LIBERTY UNIVERSITY BY ROBIN LIGON-WILLIAMS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY DECEMBER 18, 2016 Copyright: Robin Ligon-Williams, © 2016 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv. ABSTRACT vi. CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 History and Background 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Research Question 2 Glossary of Terms 4 Limitations of the Study 6 Assumptions 7 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 9 New Orleans-Port of Entry for African Culture 9 Brotherhood in Congo Square: Africans & Native Americans Unite 11 Cultural Retention: Music, Language, Masking, Procession and Ritual 13 -Musical Influence on Jazz & Rhythm & Blues 15 -Language 15 -Procession 20 -Masking: My Big Chief Wears a Golden Crown 23 -African Inspired Masking 26 -Icons of Resistance: Won’t Bow Down, Don’t Know How 29 -Juan “Saint” Maló: Epic Hero of the Maroons 30 -Black Hawk: Spiritual Warrior & Protector 34 ii. -Spiritualist Church & Ritual 37 -St. Joseph’s Day 40 3. METHODOLOGY 43 THESIS: 43 Descriptions of Research Tools/Data Collection 43 Participants in the Study 43 Academic Research Timeline 44 PROJECT 47 Overview of the Project Design 47 Relationship of the Literature to the Project Design 47 Project Plan to Completion 49 Project Implementation 49 Research Methods and Tools 50 Data Collection 50 4. IN THE FIELD 52 -Egungun Masquerade: OYOTUNJI Village 52 African Cultural Retentions 54 -Ibrahima Seck: Director of Research, Whitney Plantation Museum 54 -Andrew Wiseman: Ghanaian/Ewe, Guardians Institute 59 The Elders Speak 62 -Bishop Oliver Coleman: Spiritualist Church, Greater Light Ministries 62 -Curating the Culture: Ronald Lewis, House of Dance & Feathers 66 -Herreast Harrison: Donald Harrison Sr. -

"Throw Me Something, Mister": the History of Carnival Throws in New Orleans

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-20-2011 "Throw Me Something, Mister": The History of Carnival Throws in New Orleans Lissa Capo University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Capo, Lissa, ""Throw Me Something, Mister": The History of Carnival Throws in New Orleans" (2011). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1294. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1294 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Throw Me Something, Mister”: The History of Carnival Throws in New Orleans A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Public History by Lissa Capo B.A. Louisiana State University, 2006 May 2011 i Dedication This work is dedicated to my parents, William and Leslie Capo, who have supported me through the years. -

Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 © Copyright by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line by Benjamin Grant Doleac Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Cheryl L. Keyes, Chair The black brass band parade known as the second line has been a staple of New Orleans culture for nearly 150 years. Through more than a century of social, political and demographic upheaval, the second line has persisted as an institution in the city’s black community, with its swinging march beats and emphasis on collective improvisation eventually giving rise to jazz, funk, and a multitude of other popular genres both locally and around the world. More than any other local custom, the second line served as a crucible in which the participatory, syncretic character of black music in New Orleans took shape. While the beat of the second line reverberates far beyond the city limits today, the neighborhoods that provide the parade’s sustenance face grave challenges to their existence. Ten years after Hurricane Katrina tore up the economic and cultural fabric of New Orleans, these largely poor communities are plagued on one side by underfunded schools and internecine violence, and on the other by the rising tide of post-disaster gentrification and the redlining-in- disguise of neoliberal urban policy. -

Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 2-1986 Wavelength (February 1986) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (February 1986) 64 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/56 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSI COS50 12/31199 BULK RATE EARL KLON6 LIBRARY tnL U. S. POSTAGE UNIV OF N.O. PAID ACQUISITIONS DEPT I N.O., LA 70148 ·VV39 Lt} COL. VIITDANS AT DAVID MON. -THUR. 1o-1 0 FRI. & SAT. 10-11 SUN. NOON-9 885-4200 Movies, Music & More! METAIRIE NEWORLEANS ¢1NEW LOCATIONJ VETmiANS ..,.~ sT. AT ocTAVIA formerly Leisure Landing 1 BL EAST OF CAUSEMY MON.-SAT. 1o-10 • MON.-SAT. 1o-10 SUN. NOON-8 SUN. NOON-9 88t-4028 834-8550 f) I ISSUE NO. 64 • FEBRUARY 1986 w/m not sure. but I'm almost positive. thai all music came from New Orleans.·· Ernie K-Doe. 1979 Features Flambeaux! ...................... 18 Slidell Blues . ......... ............ 20 James Booker . .................... 23 Departments February News . 4 Caribbean . 6 New Bands ....................... 8 U.S. Indies . ...................... 10 Rock ............................ 12 16-track Master Recorder: Movies .......................... 15 Reviews ........ ................ 17 Fostex B-16 February Listings ................. 25 Classifieds ....................... 29 Last Page . ....................... 30 COVER ART BY SKIP BOLEN Two #l hits in October. Member of NetWOfk Next? Puhlhhu. 'aun1an S S.ullt f..ditc•r . -

Gayneworleans.COM • Southerndecadence.COM • Gayeasterparade.COM • Jan

GayNewOrleans.COM • SouthernDecadence.COM • GayEasterParade.COM • Jan. 30-Feb. 12, 2007 • AmbushMag.COM • MAIN~1 of 56 MAIN~2 of 56 • AmbushMag.COM • Jan. 30-Feb. 12, 2007 • The One & Only Official Gay Mardi Gras Guide • GayMardiGras.COM GayNewOrleans.COM • SouthernDecadence.COM • GayEasterParade.COM • Jan. 30-Feb. 12, 2007 • AmbushMag.COM • MAIN~3 of 56 local brass band talent is one of the few Krewe du Vieux traditions not currently the "official" dish being gutted, demolished, called into special session or waiting on a Road to Gulf South Entertainment/Travel Guide Since by Rip & Marsha Naquin-Delain Nowhere application. 1982 • Texas-Florida RipandMarsha.COM The Krewe du Vieux is a non-profit organization dedicated to the historical OFFICE/SHIPPING ADDRESS: E-mail: [email protected] 828-A Bourbon St., New Orleans, LA 70116-3137 and traditional concept of a Mardi Gras USA parade as a venue for individual creative Warden Chris Rose expression and satirical comment. It is OFFICE HOURS: 10am-3pm unique among all Mardi Gras parades Monday-Friday [Except Holidays] To Lead Inmates’ Escape because it alone carries on the old Carni- E-mail: [email protected] Parade, Krewe du Vieux val traditions, by using decorated, hand or PHONE: 1.504.522.8049 • 1.504.522.8047 mule-drawn floats with satirical themes, 2007 on Feb. 3 ANNUAL READERSHIP: accompanied by costumed revelers danc- Has there ever been a crazier 650,000+ in print/3.5 Million+ On-line ing to the sounds of jazzy street musi- year? In Washington, the Repub- cians. We believe in exposing the world to NATIONAL CIRCULATION: licans turned a few pages – and " the true nature of Mardi Gras — and in USA.. -

Mardi Gras Parades 2014

Mardi Gras Parades 2014 Date Parade Time Area 2/15/2014 Krewe of Jupiter 6:30 PM Baton Rouge 2/21/2014 Krewe of Artemis 7:00 PM Baton Rouge 2/22/2014 Krewe of Mystique 2:00 PM Baton Rouge 2/22/2014 Krewe of Orion 6:30 PM Baton Rouge 2/28/2014 Southdowns 7:00 PM Baton Rouge 3/1/2014 Spanish Town Noon Baton Rouge 2/16/2014 Krewe of Des Petite 1:00 PM Bayou Lafourche 2/22/2014 Le Krewe Des T- Cajun noon Bayou Lafourche 2/22/2014 Krewe of Ambrosia 5:30 PM Bayou Lafourche 2/23/2014 Krewe of Shaka 1:00 PM Bayou Lafourche 2/23/2014 Krewe of Versailles Noon Bayou Lafourche 2/28/2014 Krewe of Athena 7:00 PM Bayou Lafourche 3/1/2014 Krewe of Altantis noon Bayou Lafourche 3/1/2014 Krewe of Apollo Noon Bayou Lafourche 3/1/2014 Krewe of Babylon 6:00 PM Bayou Lafourche 3/1/2014 Le Krewe Du Bon Temps 5:50 PM Bayou Lafourche 3/2/2014 Krewe of Nereids 6:00 PM Bayou Lafourche 2/22/2014 Knights of Nemesis 1:00 PM Chalmette 2/22/2014 Krewe of Olympia 6:00 PM Covington 2/28/2014 Krewe of Lyra 7:00 PM Covington 2/15/2014 Krewe du Vieux 6:30 PM French Quarter 2/15/2014 Krewe Delusion du Vieux French Quarter 2/21/2014 Krewe of Cork 3:00 PM French Quarter 2/23/2014 Krewe of Barkus 2:00 PM French Quarter 2/22/2014 Krewe of Tee Caillou 12:00 PM Houma/Terrebonne 2/22/2014 Krewe of Aquarius 6:30 PM Houma/Terrebonne 2/23/2014 Krewe of Hyacinthians 12:30 PM Houma/Terrebonne 2/23/2014 Krewe of Titans Hyacin Houma/Terrebonne 2/28/2014 Krewe of Aphrodite 6:30 PM Houma/Terrebonne 3/1/2014 Krewe of Mardi Gras 6:30 PM Houma/Terrebonne 3/2/2014 Krewe of Terreanians 12:30 -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Second Line: A (Re)Conceptualization of the New Orleans Brass Band Tradition Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/09z2z2d7 Author GASPARD BOLIN, MARC TIMOTHY Publication Date 2021 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Second Line: A (Re)Conceptualization of the New Orleans Brass Band Tradition A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Marc Timothy Gaspard Bolin 2021 i © Copyright by Marc Timothy Gaspard Bolin 2021 i ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Second Line: A (Re)Conceptualization of the New Orleans Brass Band Tradition by Marc Timothy Gaspard Bolin Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor Cheryl L. Keyes, Chair In New Orleans, Louisiana, nearly every occasion is marked with a celebratory parade, most famously the Mardi Gras processions that seemingly take over the city during Carnival Time. But throughout the year, there are jazz funerals and parades known as "second lines" that fill the Backatown neighborhoods of New Orleans, with the jubilant sounds of brass band music. These peripatetic parades and their accompanying brass bands have become symbolic of New Orleans and its association with social norm-breaking and hedonistic behavior. The second line constitutes cultural practice and group identification for practitioners serving as a site for spiritual practice and renewal. In Los Angeles, California, practitioners are transposing the second line, out of which comes new modes of expression, identities, meanings, and theology. -

Kruisin' Da Krewes

Alternative Mardi Gras Kruisin’ da Krewes Vol. II, issue 2 1 Dave Malone from The Radiators Photo / Pat Jolly Where is Beat Street? There is a place in New Orleans, a figurative address that is home to all that is real. New Orleans Beat Street is the home of jazz. It is also the residence of funk and the blues; R&B and rock ‘n’ roll live here, too. When zydeco and Cajun music come to town, Beat Street is their local address. Beat Street has intersections all over town: from Uptown to Treme, from the Ninth Ward to the French Quarter, from Bywater to the Irish Channel, weaving its way through Mid-City and all points Back o’ Town. Beat Street is the Main Street in our musical village. It is where we gather to dine and to groove to live music in settings both upscale and downhome. Beat Street is where we meet to celebrate life in New Orleans with second line parades, festivals and concerts in the park. Beat Street is lined with music clubs, restaurants, art galleries, recording studios, clothing shops, coffee emporiums and so much more. New Orleans Beat Street is a mythical street in New Orleans surrounded by water and flooded with music. 2 NEW ORLEANS BEAT STREET MAGAZINE Vol. II, issue 2 3 Photo Michael P. Smith In This Issue... Beat Street takes a look at Carnival from an alternative perspective. Broderick Webb explores the East-West connections. David Kunian investigates the origins of some of the most fascinating “underground” krewes. Spike Perkins gets up close and personal with the Krewe Du Vieux. -

MF DOOM LUNCH BOX SHEET 1-2 Sm

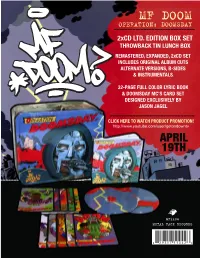

2xCD LTD. EDITION BOX SET THROWBACK TIN LUNCH BOX REMASTERED, EXPANDED, 2xCD SET INCLUDES ORIGINAL ALBUM CUTS ALTERNATE VERSIONS, B-SIDES & INSTRUMENTALS 32-PAGE FULL COLOR LYRIC BOOK & DOOMSDAY MC’S CARD SET DESIGNED EXCLUSIVELY BY JASON JAGEL CLICK HERE TO WATCH PRODUCT PROMOTION! http://www.youtube.com/user/getondowntv APRIL 19TH 2xCD LTD. EDITION BOX SET THROWBACK TIN LUNCH BOX Ask any true hip-hop fan and he can tell you exactly where and when he first heard DOOM’s Operation: Doomsday. Against seeming insurmountable odds, the album - bootlegged mercilessly, floating in and out of print on various labels since it’s release in 1999 - gained mythical status amongst music aficionados of all backgrounds as one of the landmark releases of the past decade. At its core? One man, a microphone, an MPC 2000 and a Roland VS 1680. By the time of Operation: Doomsday’s recording, DOOM was a DISC ONE DISC TWO transformed man: a veteran of hip hop’s aging “new ORIGINAL ALBUM FULL-LENGTH ALTERNATE VERSIONS, B-SIDES school” reinvented as the masked, abstract wordsmith TRACK LISTING AND INSTRUMENTALS 1 The Time We Faced Doom (Skit) 1 Dead Bent (Original 12" Version) of the NOW. His pointed wit, subtly subversive lyrics 2 Doomsday 2 Gas Drawls (Original 12" Version) 3 Rhymes Like Dimes (Featuring Cucumber 3 Hey! (Original 12" Version) 4 Greenbacks (Original 12" Version) and stream-of-consciousness flow over adventurous Slice) 5 Go With The Flow Feat. Sci.Fly (Original 12" 4 The Finest (Featuring Tommy Gunn) sample-based production created the measuring Version) 5 Back In The Days (Skit) 6 Go With The Flow (Raw Rhymes) stick by which rappers in the coming decade would 6 Go With The Flow 7 I Hear Voices Pt. -

Presidential Address PVSS 2008

Presidential Address PVSS 2008 W. Charles Sternbergh, III, MD Section Head Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Ochsner Health System New Orleans MCV, 1988 - 1995 H.M. Lee Emory 1995-1996 Elliot Alan Chaikoff Lumsden Bob Tom Atef Salam Smith Dodson Ochsner (Jazzfest 1999) Sam Money Carnival From the latin “carnelevamen” Translation: “Farewell to flesh” th Officially begins on January 6 • Twelfth Night (Feast of the Epiphany) Ends on Midnight, Fat Tuesday (Mardi Gras) Most locals refer to the 2 week season immediately prior to Mardi Gras as carnival Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday) Last day of this pre- Lenten celebration known as “carnival” Originally created by the Catholic Church for “the masses” to celebrate prior to Lent Next day is Ash Wednesday • Beginning 40 days of Lent prior to Easter When is Mardi Gras ? 47 days prior to Easter • (40 days of Lent + 7 Sundays) Always on Tuesday rd February 3 – March 9th Carnival Organizations: “Krewes” All private organizations No external funding allowed Most Krewes have a parade Riders on the floats mostly members Each member pays for his own “throws” (beads, stuffed animals, etc) • ~$ 500 – $ 2000 per person • 53 parades, 150-1500 riders per parade Krewes Most Krewes have a King and Queen • Selection process varies Some Krewes have a ball • Many connected with debutane presentation and formal tableaux Invitation only, very formal • Other with HUGE parties More fun ! Tickets can be purchased Many (but not all) Krewes parade Carnival History in New Orleans “old-line” Krewes (all male) -

Carnival Fêtes and Feasts 1

Carnival Fêtes and Feasts 1. Rex, King of Carnival, Monarch of Merriment - Rex’s float carries the King of Carnival and his pages through the streets of New Orleans each Mardi Gras. In the early years of the New Orleans Carnival Rex’s float was redesigned each year. The current King’s float, one of Carnival’s most iconic images, has been in use for over fifty years. 2. His Majesty’s Bandwagon - From this traditional permanent float one of the Royal Bands provides lively music for Rex and for those who greet him on the parade route. One of those songs will surely be the Rex anthem: “If Ever I Cease to Love,” which has been played in every Rex parade since 1872. 3. The King’s Jesters - Even the Monarch of Merriment needs jesters in his court. Rex’s jesters dress in the traditional colors of Mardi Gras – purple, green and gold. The papier mache’ figures on the Jester float are some of the oldest in the Rex parade, and were sculpted by artists in Viareggio, Italy, a city with its own rich Carnival tradition. 4. The Boeuf Gras - The Boeuf Gras (“the fat ox”) represents one of the oldest traditions and images of Mardi Gras, symbolizing the great feast on the day before Lent begins. In the early years of the New Orleans Carnival a live Boeuf Gras, decorated with garlands, had an honored place near the front of the Rex Parade. 5. The Butterfly King - Since the earliest days of Carnival, butterflies have been popular symbolic design elements, their brief and colorful life a metaphor for the ephemeral magic of Mardi Gras itself.