Christ: the Logos Incarnate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes Christiane Shaker [email protected]

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Fall 12-2016 The "Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes Christiane Shaker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Shaker, Christiane, "The "Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes" (2016). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2220. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2220 Seton Hall University THE “LAMB OF GOD” TITLE IN JOHN’S GOSPEL: BACKGROUND, EXEGESIS, AND MAJOR THEMES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THEOLOGY CONCENTRATION IN BIBLICAL THEOLOGY BY CHRISTIANE SHAKER South Orange, New Jersey October 2016 ©2016 Christiane Shaker Abstract This study focuses on the testimony of John the Baptist—“Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” [ἴδε ὁ ἀµνὸς τοῦ θεοῦ ὁ αἴρων τὴν ἁµαρτίαν τοῦ κόσµου] (John 1:29, 36)—and its impact on the narrative of the Fourth Gospel. The goal is to provide a deeper understanding of this rich image and its influence on the Gospel. In an attempt to do so, three areas of concentration are explored. First, the most common and accepted views of the background of the “Lamb of God” title in first century Judaism and Christianity are reviewed. -

John 1-21 – Review (Part 1)

John 1-21 – Review (Part 1) In our half-way review, which included the first 12 chapters, our lists were not complete. John likes the numbers 3, 7 and 12. The Gospel of John talks about the seven witnesses to Jesus. Five are mentioned in chapter five and the other two are mentioned in chapter fifteen. The Seven Witnesses. 1. Jesus Himself. 5:31, 8:14 2. John the Baptist. 5:33-35 3. The signs which Jesus accomplished. 5:36 4. God the Father. 5:37-38 5. Scripture. 5:39-40 6. The Holy Spirit. 15:26 7. The 11 disciples. 15:27 John only selected seven signs out of the many signs which Jesus performed. Some of the signs backed up his “I am” statements. Jesus’ signs manifested his glory (2:11). The purpose of the signs is that people might believe in Jesus. (2:11, 20:30-31) The Seven Signs. 1. Changing water to wine at the wedding in Cana. 2:1-11 2. Healing the son of an official via long distance (Cana to Capernaum). 4:46-54 3. Healing the man who was lame for 38 years. 5:1-16 4. Feeding over five thousand people from five loaves of bread and two fish. 6:1-14 (I am the Bread of Life) 5. Giving sight to a man who was born blind. 9:1-38 (I am the Light of the world) 6. Raising Lazarus from the dead who had been in the tomb for four days. 11:1-44 (I am the Resurrection and the Life) 7. -

Logos Catalog

ID Name Picture bhstcmot Bible History Commentary: Old Testament $45.50 Excellent tool for teachers - elementary, Sunday school, vacation Bible school, Bible class--and students. Franzmann clarifies historical accounts, explains difficult passages, offers essential background information, warns about misapplications of the biblical narrative, and reminds readers of the gospel. Contains maps, illustrated charts and tables, a Hebrew calendar, indexes of proper names and Scripture references, and an explanation of biblical chronology. The mission of Northwestern Publishing House is to deliver biblically sound Christ- centered resources within the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod and beyond. The vision of Northwestern Publishing House is to be the premier resource for quality Lutheran materials faithful to the Scriptures and Lutheran confessions. NPH publishes materials for worship, vacation Bible school, Sunday school, and several other ministries. The NPH headquarters are located in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. BHSWTS42 Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS Hebrew): With Westminster $99.95 4.2 Morphology This edition of the complete Hebrew Bible is a reproduction of the Michigan-Claremont-Westminster text (MCWT) with Westminster Morphology (WM, version 4.2, 2004). The MCWT is based closely on the 1983 edition of Biblica Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS). As of version 2.0, however, MCWT introduced differences between the editions, based on new readings of Codex Leningradensis b19A (L). The MCWT was collated both computationally and manually against various other texts, including Kittel's Biblia Hebraica (BHK), the Michigan-Claremont electronic text. Additionally, manual collations were made using Aron Dotan's The Holy Scriptures and BHK. The Westiminster morphological database adds a complete morphological analysis for each word/morpheme of the Hebrew text. -

Nicodemus and the New Birth

SESSION EIGHT Nicodemus and the New Birth SESSION SUMMARY This session depicts a conversation in which Jesus taught a religious leader, Nicodemus, about the mystery of regeneration—what He described as “being born again.” Christians have been born again by the Spirit of God, through faith in God’s Son. The new birth is the basis of our confidence that God is at work transforming us and all who believe in the gospel. SCRIPTURE John 3:1-21 86 Leader Guide / Session 8 THE POINT Regeneration is God’s supernatural transformation of believers. INTRO/STARTER 5-10 MINUTES Option 1 Toy commercials are usually filled with action. They show kids having fun as they play with whatever product is being promoted. They highlight the gadget’s best features in a way that appeals to a child’s sense of imagination. But at the end, a narrator usually comes on and makes a disclaimer: “Batteries not included.” Most likely, there were numerous occasions when well-meaning parents or guardians purchased a toy their child wanted without realizing there were no batteries in the box—unbearable disappointment in the eyes of a child! The kid feels duped, the parent is embarrassed, and the moment of bliss fades away because the toy can’t function. • When have you been disappointed by something not functioning as you thought it would? What was the reason for the item’s inability to function? As Christians, we believe salvation is a gift. God our Father has shown us grace in giving us salvation. But unlike those disappointing toy commercials, this gift doesn’t need a disclaimer that says “batteries are not included.” The good news about God’s gift is that, alongside forgiveness of sins, we receive the Holy Spirit. -

Part I: Explaining the Biblical Term 'Son(S) of God' in Muslim Contexts

Delicate Issues in Mission Part I: Explaining the Biblical Term ‘Son(s) of God’ in Muslim Contexts by Rick Brown The Problem for Muslims n some languages and people groups, sonship terminology is used almost exclusively for direct biological relationships, i.e., it means the same as I ‘offspring’ in English. In Classical Arabic, for example, the counterparts for ‘son’ and ‘father’ mean biological son and biological father. These terms were not used metaphorically for other interpersonal relationships, not even for a nephew, a step-son, or an adopted son.1 One did not normally call someone else ibnî “my son” as a term of endearment, because it could suggest a claim of paternity, with all that this entailed. The Arabic usage contrasts signifi cantly with the situation in Hebrew and Aramaic (and Akkadian), where one could address his son, grandson, nephew, son-in-law, and neighbor’s son as bnî / brî ‘my son’ and the female counter- parts as bittî / bratî ‘my daughter’. (The plural of ‘son’ was gender inclusive.) The disciples of a prophet, rabbi, or craftsman could be called his “sons.” The citizens of a kingdom could be called the king’s “sons,” and a paramount king could refer to his vice-regent or viceregal king as his “son.” Speaking through the prophets in language the people could understand, God called his people his “son” and his faithful servants his “sons.” He was their king and the king of kings, so when he set David over them has his viceregal king, he called David his “son,” and similarly with King Solomon and a King he said would arise from their lineage. -

The Real Story of the Real Savior 1 John 1:1-4

The Real Story of the Real Savior 1 John 1:1-4 Broadcast Dates: Jun 3 & 4, 2020 Steve DeWitt It was 19 years ago now that God did a transformation in my life. I had served for a year as a youth pastor at a church in Indianapolis. The kids were mostly uninterested. I had a few who were hostile. In spite of my efforts, things were in pretty rough shape. I went to the senior pastor one day and said, “I don’t know what to do. These kids don’t really care and my messages don’t seem to get through.” He looked at me and asked about those messages. I described what I did generally and frankly, I mostly winged it with them on subjects I thought they might like. He challenged me to teach them the Bible with the same care and concern I would if I was teaching adults. He said words that the Holy Spirit used to pierce my heart, "What if David would have said, 'Oh these few small sheep.'"? I left that meeting a changed man and I began to actually teach the Bible to the kids and God did some wonderful things. The very first expository series I ever taught coming out of that change was 1 John. It has been special to me ever since. Introduction to 1 John Who wrote it? Unlike most other New Testament books, the author doesn’t identify himself. In this case, it is easily identified as the apostle John. His language and style are very similar to the gospel of John. -

ABHE Essentials Full List of Titles

ABHE Essentials Full List of Titles • Logos Full Feature Set • Intermediate New Testament Greek • Atlas of Christian History • Key to the Elements of New Testament Greek • Holman Bible Atlas • The Elements of New Testament Greek • English Standard Version Audio • Theological Lexicon of the New Testament • Lexham English Bible Audio • The Greek New Testament: SBL Edition • Dictionary of Bible Themes • A Biblical Hebrew Reference Grammar • Eerdmans Bible Dictionary • Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon • Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary • Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar, 2nd English Edition • Lexham Bible Dictionary • Grammar of Biblical Hebrew • The New Bible Dictionary, Third Edition • Lexham Theological Wordbook • The Treasury of Scripture Knowledge • Theological Lexicon of the Old Testament • An Introduction to the New Testament • Lexham Hebrew Bible • Bible Knowledge Commentary • Basic Bible Interpretation: A Practical Guide to Discovering • Evangelical Commentary on the Bible Biblical Truth • IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament, 2nd ed • Glossary of Morpho-Syntactic Database Terminology • IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament • The Lexham English Septuagint • New American Commentary (42 vols.) • The Lexham English Septuagint: Alternate Texts • New Bible Commentary • The Old Testament in Greek according to the Septuagint • Tyndale Commentaries (58 vols) • The Old Testament in Greek according to the Septuagint • New Testament Theology: Many Witnesses, One Gospel (Alternate Texts) • Old Testament Theology, -

SCRIPTURES for SUNDAY 2.18.2018 Today’S Scripture Is Filled with Contrasts and Paradoxes

SCRIPTURES FOR SUNDAY 2.18.2018 Today’s scripture is filled with contrasts and paradoxes. Jesus is the word, from the beginning, in whom is life. Yet here we see that the life he gives to Lazarus, raising him from John 11:1-45 the dead, is the very thing that leads to his death. This story New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) is followed by John 11:45-54 which concludes with the narrative explanation “So from that day on [the ruling 1 council of the chief priests and the Pharisees] planned to put Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, the Jesus to death.” village of Mary and her sister Martha. 2 Mary was the one who anointed the Lord with perfume and All of the miraculous signs of Jesus point to who he is and I am wiped his feet with her hair; her brother Lazarus was what he has come to give humanity (and are followed by the 3 statements in John’s gospel). None of them are more ill. So the sisters sent a message to Jesus, “Lord, he 4 closely related to the reality of resurrection life through his whom you love is ill.” But when Jesus heard it, he resurrection than this story of Lazarus rising from the dead. said, “This illness does not lead to death; rather it is Bethany for God’s glory, so that the Son of God may be : Today the town of Bethany, just east of Jerusalem, glorified through it.” 5 Accordingly, though Jesus loved 6 Maryis called “El ‘Azariyeh” and her sister– a Marthaname derived from “Lazarus”. -

The Abrahamic Faiths

8: Historical Background: the Abrahamic Faiths Author: Susan Douglass Overview: This lesson provides background on three Abrahamic faiths, or the world religions called Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It is a brief primer on their geographic and spiritual origins, the basic beliefs, scriptures, and practices of each faith. It describes the calendars and major celebrations in each tradition. Aspects of the moral and ethical beliefs and the family and social values of the faiths are discussed. Comparison and contrast among the three Abrahamic faiths help to explain what enabled their adherents to share in cultural, economic, and social life, and what aspects of the faiths might result in disharmony among their adherents. Levels: Middle grades 6-8, high school and general audiences Objectives: Students will: Define “Abrahamic faith” and identify which world religions belong to this group. Briefly describe the basic elements of the origins, beliefs, leaders, scriptures and practices of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Compare and contrast the basic elements of the three faiths. Explain some sources of harmony and friction among the adherents of the Abrahamic faiths based on their beliefs. Time: One class period, or outside class assignment of 1 hour, and ca. 30 minutes class discussion. Materials: Student Reading “The Abrahamic Faiths”; graphic comparison/contrast handout, overhead projector film & marker, or whiteboard. Procedure: 1. Copy and distribute the student reading, as an in-class or homework assignment. Ask the students to take notes on each of the three faith groups described in the reading, including information about their origins, beliefs, leaders, practices and social aspects. They may create a graphic organizer by folding a lined sheet of paper lengthwise into thirds and using these notes to complete the assessment activity. -

The Occult Teachings of the Christ According to the Secret Doctrine By: Josephine Ransom

Adyar Pamphlets The Occult Teachings of the Christ... No. 179 The Occult Teachings of the Christ According to the Secret Doctrine by: Josephine Ransom The Blavatsky Lecture, delivered before the Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society in England, 1933 The references are to the original Secret Doctrine by H.P.Blavatsky , published in 1888 Published in 1933 Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, Chennai [Madras] India The Theosophist Office, Adyar, Madras. India “For the teachings of Christ were Occult teachings, which could only be explained at Initiation” [ Secret Doctrine, Volume 2, Page 241] I In presenting my theme I must make it clear that I have drawn solely upon The Secret Doctrine for information. I have not sought elsewhere for corroboration or amplification of any point, save a few quotations from the Bible and have made but few comments myself. I leave it to the students to seek their own answers to the question that must inevitably arise in their minds as the story unfolds. For the sake of a sequence these questions are essential: (1) Who was the Christ? (2) Who was Jesus? [Page 2] (3) What were the Occult Teachings of the Christ? (1) Who was the Christ? The answer comes clearly:“The Logos is Christos.....” (S.D. 1, 241) “......There are three kinds of Light in Occultism .....(1) The Abstract and Absolute Light, which is Darkness; (2) The Light of the Manifested — Unmanifested, called by some the Logos; and (3) The latter Light reflected in the Dhyân Chohans, the minor Logoi — the Elohim, collectively — who, in their turn, shed it on the objective Universe.....” “The Occultists in the East call this Light Daiviprakriti, and in the West the Light of Christos. -

19Th Sunday in Ordinary Time W O R S H I P a I D E

19th Sunday in Ordinary Time W O R S H I P A I D E ST. PAUL CATHOLIC CHURCH · AUGUST 8, 2021 2 1 6 N A S S A U S T R E E T · P R I N C E T O N , N J · 0 8 5 4 2 · 6 0 9 - 9 2 4 - 1 7 4 3 · S T P A U L S O F P R I N C E T O N . O R G INTRODUCTORY RITES GLORIA Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to people of good will. ENTRANCE We praise you, we bless you, WHERE CHARITY AND LOVE PREVAIL we adore you, we glorify you, we give you thanks for your great glory, Lord God, heavenly King, O God, almighty Father. Lord Jesus Christ, Only Begotten Son, Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father, you take away the sins of the world, have mercy on us; you take away the sins of the world, receive our prayer; you are seated at the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us. For you alone are the Holy One, you alone are the Lord, you alone are the Most High, Jesus Christ, with the Holy Spirit, in the glory of God the Father. Amen. COLLECT Priest: ...Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unit of the Holy Spirit GREETING God, for ever and ever. Priest: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God and the communion of the Holy People: Amen. -

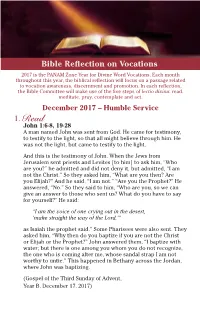

December Reflection: Humble Service

Bible Reflection on Vocations 2017 is the PANAM Zone Year for Divine Word Vocations. Each month throughout this year, the biblical reflection will focus on a passage related to vocation awareness, discernment and promotion. In each reflection, the Bible Committee will make use of the five steps of lectio divina: read, meditate, pray, contemplate and act. December 2017 – Humble Service 1. Read John 1:6-8, 19-28 A man named John was sent from God. He came for testimony, to testify to the light, so that all might believe through him. He was not the light, but came to testify to the light. And this is the testimony of John. When the Jews from Jerusalem sent priests and Levites [to him] to ask him, “Who are you?” he admitted and did not deny it, but admitted, “I am not the Christ.” So they asked him, “What are you then? Are you Elijah?” And he said, “I am not.” “Are you the Prophet?” He answered, “No.” So they said to him, “Who are you, so we can give an answer to those who sent us? What do you have to say for yourself?” He said: “I am the voice of one crying out in the desert, ‘make straight the way of the Lord,’” as Isaiah the prophet said.” Some Pharisees were also sent. They asked him, “Why then do you baptize if you are not the Christ or Elijah or the Prophet?” John answered them, “I baptize with water; but there is one among you whom you do not recognize, the one who is coming after me, whose sandal strap I am not worthy to untie.” This happened in Bethany across the Jordan, where John was baptizing.