The Courts and the 'Rule of Law' in Singapore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rule of Law and Urban Development

The Rule of Law and Urban Development The transformation of Singapore from a struggling, poor country into one of the most affluent nations in the world—within a single generation—has often been touted as an “economic miracle”. The vision and pragmatism shown by its leaders has been key, as has its STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS notable political stability. What has been less celebrated, however, while being no less critical to Singapore’s urban development, is the country’s application of the rule of law. The rule of law has been fundamental to Singapore’s success. The Rule of Law and Urban Development gives an overview of the role played by the rule of law in Singapore’s urban development over the past 54 years since independence. It covers the key principles that characterise Singapore’s application of the rule of law, and reveals deep insights from several of the country’s eminent urban pioneers, leaders and experts. It also looks at what ongoing and future The Rule of Law and Urban Development The Rule of Law developments may mean for the rule of law in Singapore. The Rule of Law “ Singapore is a nation which is based wholly on the Rule of Law. It is clear and practical laws and the effective observance and enforcement and Urban Development of these laws which provide the foundation for our economic and social development. It is the certainty which an environment based on the Rule of Law generates which gives our people, as well as many MNCs and other foreign investors, the confidence to invest in our physical, industrial as well as social infrastructure. -

![[2020] SGCA 16 Civil Appeal No 99 of 2019 Between Wham Kwok Han](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5871/2020-sgca-16-civil-appeal-no-99-of-2019-between-wham-kwok-han-155871.webp)

[2020] SGCA 16 Civil Appeal No 99 of 2019 Between Wham Kwok Han

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2020] SGCA 16 Civil Appeal No 99 of 2019 Between Wham Kwok Han Jolovan … Appellant And The Attorney-General … Respondent Civil Appeal No 108 of 2019 Between Tan Liang Joo John … Appellant And The Attorney-General … Respondent Civil Appeal No 109 of 2019 Between The Attorney-General … Appellant And Wham Kwok Han Jolovan … Respondent Civil Appeal No 110 of 2019 Between The Attorney-General … Appellant And Tan Liang Joo John … Respondent In the matter of Originating Summons No 510 of 2018 Between The Attorney-General And Wham Kwok Han Jolovan In the matter of Originating Summons No 537 of 2018 Between The Attorney-General And Tan Liang Joo John ii JUDGMENT [Contempt of Court] — [Scandalising the court] [Contempt of Court] — [Sentencing] iii This judgment is subject to final editorial corrections approved by the court and/or redaction pursuant to the publisher’s duty in compliance with the law, for publication in LawNet and/or the Singapore Law Reports. Wham Kwok Han Jolovan v Attorney-General and other appeals [2020] SGCA 16 Court of Appeal — Civil Appeals Nos 99, 108, 109 and 110 of 2019 Sundaresh Menon CJ, Andrew Phang Boon Leong JA, Judith Prakash JA, Tay Yong Kwang JA and Steven Chong JA 22 January 2020 16 March 2020 Judgment reserved. Sundaresh Menon CJ (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction 1 These appeals arise out of HC/OS 510/2018 (“OS 510”) and HC/OS 537/2018 (“OS 537”), which were initiated by the Attorney-General (“the AG”) to punish Mr Wham Kwok Han Jolovan (“Wham”) and Mr Tan Liang Joo John (“Tan”) respectively for contempt by scandalising the court (“scandalising contempt”) under s 3(1)(a) of the Administration of Justice (Protection) Act 2016 (Act 19 of 2016) (“the AJPA”). -

Rule of Law Without Democratization: Cambodia and Singapore in Comparative Perspective

Griffith Asia Institute Research Paper Rule of Law without Democratization: Cambodia and Singapore in Comparative Perspective Stephen McCarthy and Kheang Un ii About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute produces relevant, interdisciplinary research on key developments in the politics, security and economies of the Asia-Pacific. By promoting knowledge of Australia’s changing region and its importance to our future, the Griffith Asia Institute seeks to inform and foster academic scholarship, public awareness and considered and responsive policy making. The Institute’s work builds on a long Griffith University tradition of providing multidisciplinary research on issues of contemporary significance in the region. Griffith was the first University in the country to offer Asian Studies to undergraduate students and remains a pioneer in this field. This strong history means that today’s Institute can draw on the expertise of some 50 Asia–Pacific focused academics from many disciplines across the university. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Research Papers’ publish the institute’s policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asiainstitute ‘Rule of Law without Democratization: Cambodia and Singapore in Comparative Perspective’ 2018 iii About the Authors Stephen McCarthy Stephen McCarthy is a Senior Lecturer in South East Asian politics in the School of Government and International Relations and a member of the Griffith Asia Institute at Griffith University. He received his PhD in political science from Northern Illinois University and has published widely on Burmese politics and South East Asia in international journals including The Pacific Review, Asian Survey, Pacific Affairs, Democratization and International Political Science Review. -

The Evolution of the Singapore Criminal Justice Process

(2019) 31 SAcLJ 1042 (Published on e-First 23 July 2019) THE EVOLUTION OF THE SINGAPORE CRIMINAL JUSTICE PROCESS This article analyses the Singapore criminal justice process in the context of Herbert Packer’s Crime Control and Due Process models. It begins by analysing the features and goals of the two models before applying them to recent changes and developments in the Singapore criminal justice system. The article will focus in particular on developments in societal attitudes and values, legislative and executive policy, detention without trial, amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code (Cap 68, 2012 Rev Ed), the statement of facts in guilty-plea cases, Kadar disclosure and the judicial discretion to exclude evidence. Following an analysis of these developments, the article will then assess the change in balance between the two models in the Singapore criminal justice system as well as comment on the trend and future of our criminal justice process. Keith Jieren THIRUMARAN LLB (Hons) (National University of Singapore) I. Introduction 1 The criminal justice process is the backbone of society that provides the context in which the substantive criminal law operates. The process includes all the activities “that operate to bring the substantive law of crime to bear (or to keep it from coming to bear)” on accused persons.1 In his seminal book2 and article,3 Herbert Packer espoused two renowned models that elucidate the framework for analysing the criminal justice process: the Crime Control Model and the Due Process Model. This article will analyse the unique Singapore criminal justice process to determine where it currently lies on the spectrum between the two models. -

The War on Terrorism and the Internal Security Act of Singapore

Damien Cheong ____________________________________________________________ Selling Security: The War on Terrorism and the Internal Security Act of Singapore DAMIEN CHEONG Abstract The Internal Security Act (ISA) of Singapore has been transformed from a se- curity law into an effective political instrument of the Singapore government. Although the government's use of the ISA for political purposes elicited negative reactions from the public, it was not prepared to abolish, or make amendments to the Act. In the wake of September 11 and the international campaign against terrorism, the opportunity to (re)legitimize the government's use of the ISA emerged. This paper argues that despite the ISA's seeming importance in the fight against terrorism, the absence of explicit definitions of national security threats, either in the Act itself, or in accompanying legislation, renders the ISA susceptible to political misuse. Keywords: Internal Security Act, War on Terrorism. People's Action Party, Jemaah Islamiyah. Introduction In 2001/2002, the Singapore government arrested and detained several Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) operatives under the Internal Security Act (ISA) for engaging in terrorist activities. It was alleged that the detained operatives were planning to attack local and foreign targets in Singa- pore. The arrests outraged human rights groups, as the operation was reminiscent of the government's crackdown on several alleged Marxist conspirators in1987. Human rights advocates were concerned that the current detainees would be dissuaded from seeking legal counsel and subjected to ill treatment during their period of incarceration (Tang 1989: 4-7; Frank et al. 1991: 5-99). Despite these protests, many Singaporeans expressed their strong support for the government's actions. -

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

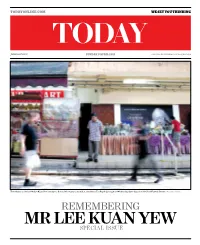

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

1 International Justice Forum 2019 MANAGING

International Justice Forum 2019 MANAGING QUALITY OF JUSTICE: GLOBAL TRENDS AND BEST PRACTICES Justice Steven Chong I. Introduction 1. In the global discourse on justice and quality of justice, much has been said about the substantive aspects of the law and justice – the importance of developing sound legal principles, a consistent body of jurisprudence, and adherence to the rule of law ideal. Somewhat less has been said of the procedural aspects – the legal rules of procedure which balance due process and the efficient running of the system. But almost nothing is said of what, in my view, is a matter oft-overlooked, and yet of critical importance – court administration and management. 2. The judiciary is, of course, an organ of state, but it is also, elementally, an organisation. Like any organisation, the courts face issues of administration and management – budgeting, human resources, public communications – and failings in these respects are just as much a threat to the administration of justice as are failings in the quality of its decisions. The key to success lies not just in elocution, but in execution; and failure lurks not just in the spectacular, but in the mundane as well. 3. This pragmatic thinking is almost hardwired into the Singaporean consciousness. Our founding Prime Minister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, himself a former lawyer, put it this way: “The acid test of any legal system is not the Judge of Appeal, Supreme Court of Singapore. I wish to acknowledge the valuable assistance of my law clerk, Mr Reuben Ong, in the research of this paper. 1 greatness or grandeur of its ideal concepts, but whether in fact it is able to produce order and justice in the relationships between man and man and between man and the State.”1 Being an island-nation with no natural resources and a tiny population entirely dependent on entrepot trade and foreign investment, the development of a robust, respected and sophisticated legal system which commands the confidence of foreign traders and investors is nothing less than a matter of survival for us. -

![Eu Kong Weng V Singapore Medical Council [2011]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6768/eu-kong-weng-v-singapore-medical-council-2011-996768.webp)

Eu Kong Weng V Singapore Medical Council [2011]

Eu Kong Weng v Singapore Medical Council [2011] SGHC 68 Case Number : Originating Summons No 829 of 2010 Decision Date : 17 March 2011 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Chan Sek Keong CJ; Andrew Phang Boon Leong JA; V K Rajah JA Counsel Name(s) : Edwin Tong, Tham Hsu Hsien, Jacqueline Chua and Magdelene Sim (Allen & Gledhill LLP) for the appellant; Tan Chee Meng SC, Chang Man Phing, Kwek Lijun Kylee and Ung Ewe Hong Maxine (WongPartnership LLP) for the respondent. Parties : Eu Kong Weng — Singapore Medical Council Professions – Medical Profession and Practice 17 March 2011 Judgment reserved. Chan Sek Keong CJ (delivering the judgment of the court): 1 We provide herewith our grounds of judgment. Our findings are as follows. This is an appeal by Dr Eu Kong Weng (“Dr Eu”) against the Disciplinary Committee’s (“DC”) decision on conviction and sentence. The DC found Dr Eu guilty of professional misconduct under section 45(1)(d) of the Medical Registration Act (Cap 174, 2004 Rev Ed) (“the Act”) on one charge of failure to obtain informed consent from one Ang Gee Kwang (“Ang”) for a staple haemorrhoidectomy (“SH”). The DC imposed a three-month suspension on Dr Eu, ordered that Dr Eu be censured, that he give a written undertaking to the Singapore Medical Council (“the SMC”) to refrain from similar conduct, and that he pay 70% of the costs. 2 The facts are as follows. On 10 July 2006, Ang consulted Dr Eu and was diagnosed with fourth degree piles. Ang alleged that the only treatment options Dr Eu discussed were a colonoscopy and SH. -

Valedictory Reference in Honour of Justice Chao Hick Tin 27 September 2017 Address by the Honourable the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

VALEDICTORY REFERENCE IN HONOUR OF JUSTICE CHAO HICK TIN 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 ADDRESS BY THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE SUNDARESH MENON -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon Deputy Prime Minister Teo, Minister Shanmugam, Prof Jayakumar, Mr Attorney, Mr Vijayendran, Mr Hoong, Ladies and Gentlemen, 1. Welcome to this Valedictory Reference for Justice Chao Hick Tin. The Reference is a formal sitting of the full bench of the Supreme Court to mark an event of special significance. In Singapore, it is customarily done to welcome a new Chief Justice. For many years we have not observed the tradition of having a Reference to salute a colleague leaving the Bench. Indeed, the last such Reference I can recall was the one for Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, which happened on this very day, the 27th day of September, exactly 27 years ago. In that sense, this is an unusual event and hence I thought I would begin the proceedings by saying something about why we thought it would be appropriate to convene a Reference on this occasion. The answer begins with the unique character of the man we have gathered to honour. 1 2. Much can and will be said about this in the course of the next hour or so, but I would like to narrate a story that took place a little over a year ago. It was on the occasion of the annual dinner between members of the Judiciary and the Forum of Senior Counsel. Mr Chelva Rajah SC was seated next to me and we were discussing the recently established Judicial College and its aspiration to provide, among other things, induction and continuing training for Judges. -

Parliament Sitting Date: 17 Aug 1999 ISSUES RAISED by PRESIDENT

Parliament Sitting Date: 17 Aug 1999 ISSUES RAISED BY PRESIDENT ONG TENG CHEONG AT HIS PRESS CONFERENCE ON 16TH JULY 1999 (Parliamentary Q&As) Mr Jeyaretnam: May I ask the Prime Minister a question or two? I understood him to say that the Cabinet would have been happier if the President had decided to seek re-election. But the Cabinet was concerned whether he was medically capable. But the President had said in his statement that his doctors had given him a clean bill, that his cancer was in complete remission and the President clearly indicated that his health would not stand in the way of his becoming President. May I ask the Prime Minister to explain to this House on what basis or information did the Cabinet conclude that he would not be capable of discharging his duties? Mr Goh Chok Tong: Mr Speaker, Sir, yes, the President had told the public at his press conference regarding his present health situation. But the Cabinet had two medical reports, one from the President's doctor in the United States, Dr Saul Rosenberg, and the other from his physician in Singapore. We studied the reports and it was quite clear from the reports that if you should focus or project the President's health condition into the future, there was a very strong likelihood that he would not be able to perform his duties normally. In a sense, it is like looking at a glass of water, whether it is one-third full or two-thirds empty. The Cabinet had to take the advice of the doctor and take a very careful view of what the President's future condition would be like. -

Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia

TRANSPARENCY AND AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA The 1997–98 Asian economic crisis raised serious questions for the remaining authoritarian regimes in Southeast Asia, not least the hitherto outstanding economic success stories of Singapore and Malaysia. Could leaders presiding over economies so heavily dependent on international capital investment ignore the new mantra among multilateral financial institutions about the virtues of ‘transparency’? Was it really a universal functional requirement for economic recovery and advancement? Wasn’t the free flow of ideas and information an anathema to authoritarian rule? In Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia Garry Rodan rejects the notion that the economic crisis was further evidence that ulti- mately capitalism can only develop within liberal social and political insti- tutions, and that new technology necessarily undermines authoritarian control. Instead, he argues that in Singapore and Malaysia external pres- sures for transparency reform were, and are, in many respects, being met without serious compromise to authoritarian rule or the sanctioning of media freedom. This book analyses the different content, sources and significance of varying pressures for transparency reform, ranging from corporate dis- closures to media liberalisation. It will be of equal interest to media analysts and readers keen to understand the implications of good governance debates and reforms for democratisation. For Asianists this book offers sharp insights into the process of change – political, social and economic – since the Asian crisis. Garry Rodan is Director of the Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University, Australia. ROUTLEDGECURZON/CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES Edited by Kevin Hewison and Vivienne Wee 1 LABOUR, POLITICS AND THE STATE IN INDUSTRIALIZING THAILAND Andrew Brown 2 ASIAN REGIONAL GOVERNANCE: CRISIS AND CHANGE Edited by Kanishka Jayasuriya 3 REORGANISING POWER IN INDONESIA The politics of oligarchy in an age of markets Richard Robison and Vedi R.