The Future of Australian LNG Exports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F O R Im M E D Ia T E R E L E A

Article No. 8115 Available on www.roymorgan.com Link to Roy Morgan Profiles Friday, 30 August 2019 Powershop still number one in electricity satisfaction, despite losing spark in recent months Powershop has won the Roy Morgan Electricity Provider of the Month Award with a customer satisfaction rating of 78% for July 2019. Powershop has now won the past seven monthly awards, remaining unbeaten in 2019. Powershop’s customer satisfaction rating of 78% was followed by Lumo Energy (71%), Simply Energy (70%), Click Energy (70%), Red Energy (70%) and Alinta Energy (70%). E These are the latest findings from the Roy Morgan Single Source survey derived from in-depth face-to- face interviews with 1,000 Australians each week and over 50,000 each year. Powershop managed to maintain its number one position in customer satisfaction, despite it recording the largest decline in ratings of any leading provider, falling from 87% in January 2019, to 78% (-9%) as of July 2019. Over the same period, Lumo Energy, Simply Energy and Click Energy all fell by 4%, Red Energy remained steady, and Alinta Energy increased its rating by 1%. Although Powershop remains well clear of its competitors, if its consistent downtrend in ratings continues for the next few months, we may well see another electricity provider take the lead in customer satisfaction. The Roy Morgan Customer Satisfaction Awards highlight the winners but this is only the tip of the iceberg. Roy Morgan tracks customer satisfaction, engagement, loyalty, advocacy and NPS across a wide range of industries and brands. This data can be analysed by month for your brand and importantly your competitive set. -

Code Security Description ARI Arrium Ltd AWC Alumina Ltd AWE AWE

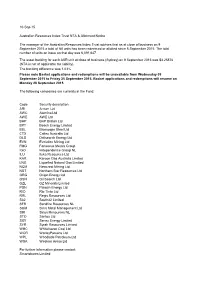

10-Sep-15 Australian Resources Index Trust NTA & Allotment Notice The manager of the Australian Resources Index Trust advises that as at close of business on 9 September 2015 a total of Nil units has been redeemed or allotted since 8 September 2015. The total number of units on issue on that day was 6,091,647. The asset backing for each ASR unit at close of business (Sydney) on 9 September 2015 was $3.25876 (NTA is net of applicable tax liability). The tracking difference was 1.03% Please note Basket applications and redemptions will be unavailable from Wednesday 09 September 2015 to Friday 25 September 2015. Basket applications and redemptions will resume on Monday 28 September 2015. The following companies are currently in the Fund: Code Security description ARI Arrium Ltd AWC Alumina Ltd AWE AWE Ltd BHP BHP Billiton Ltd BPT Beach Energy Limited BSL Bluescope Steel Ltd CTX Caltex Australia Ltd DLS Drillsearch Energy Ltd EVN Evolution Mining Ltd FMG Fortescue Metals Group IGO Independence Group NL ILU Iluka Resources Ltd KAR Karoon Gas Australia Limited LNG Liquefied Natural Gas Limited NCM Newcrest Mining Ltd NST Northern Star Resources Ltd ORG Origin Energy Ltd OSH Oil Search Ltd OZL OZ Minerals Limited PDN Paladin Energy Ltd. RIO Rio Tinto Ltd RRL Regis Resources Ltd S32 South32 Limited SFR Sandfire Resources NL SGM Sims Metal Management Ltd SIR Sirius Resources NL STO Santos Ltd SXY Senex Energy Limited SYR Syrah Resources Limited WHC Whitehaven Coal Ltd WOR WorleyParsons Ltd WPL Woodside Petroleum Ltd WSA Western Areas Ltd For further information please contact: Smartshares Limited 0800 80 87 80 [email protected]. -

Victorian Energy Prices July 2017

Victorian Energy Prices July 2017 An update report on the Victorian Tarif-Tracking Project Disclaimer The energy offers, tariffs and bill calculations presented in this report and associated workbooks should be used as a general guide only and should not be relied upon. The workbooks are not an appropriate substitute for obtaining an offer from an energy retailer. The information presented in this report and the workbooks is not provided as financial advice. While we have taken great care to ensure accuracy of the information provided in this report and the workbooks, they are suitable for use only as a research and advocacy tool. We do not accept any legal responsibility for errors or inaccuracies. The St Vincent de Paul Society and Alviss Consulting Pty Ltd do not accept liability for any action taken based on the information provided in this report or the associated workbooks or for any loss, economic or otherwise, suffered as a result of reliance on the information presented. If you would like to obtain information about energy offers available to you as a customer, go to the Victorian Government’s website www.switchon.vic.gov.au or contact the energy retailers directly. Victorian Energy Prices July 2017 An update report on the Victorian Tariff-Tracking Project May Mauseth Johnston, September 2017 Alviss Consulting Pty Ltd © St Vincent de Paul Society and Alviss Consulting Pty Ltd This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Ctw), no parts may be adapted, reproduced, copied, stored, distributed, published or put to commercial use without prior written permission from the St Vincent de Paul Society. -

Asx Clear – Acceptable Collateral List 28

et6 ASX CLEAR – ACCEPTABLE COLLATERAL LIST Effective from 20 September 2021 APPROVED SECURITIES AND COVER Subject to approval and on such conditions as ASX Clear may determine from time to time, the following may be provided in respect of margin: Cover provided in Instrument Approved Cover Valuation Haircut respect of Initial Margin Cash Cover AUD Cash N/A Additional Initial Margin Specific Cover N/A Cash S&P/ASX 200 Securities Tiered Initial Margin Equities ETFs Tiered Notes to the table . All securities in the table are classified as Unrestricted (accepted as general Collateral and specific cover); . Specific cover only securities are not included in the table. Any securities is acceptable as specific cover, with the exception of ASX securities as well as Participant issued or Parent/associated entity issued securities lodged against a House Account; . Haircut refers to the percentage discount applied to the market value of securities during collateral valuation. ASX Code Security Name Haircut A2M The A2 Milk Company Limited 30% AAA Betashares Australian High Interest Cash ETF 15% ABC Adelaide Brighton Ltd 30% ABP Abacus Property Group 30% AGL AGL Energy Limited 20% AIA Auckland International Airport Limited 30% ALD Ampol Limited 30% ALL Aristocrat Leisure Ltd 30% ALQ ALS Limited 30% ALU Altium Limited 30% ALX Atlas Arteria Limited 30% AMC Amcor Ltd 15% AMP AMP Ltd 20% ANN Ansell Ltd 30% ANZ Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd 20% © 2021 ASX Limited ABN 98 008 624 691 1/7 ASX Code Security Name Haircut APA APA Group 15% APE AP -

2020 Shell in Australia Modern Slavery Statement

DocuSign Envelope ID: D3E27182-0A3B-4D38-A884-F3C2C5F0C272 JOINT MODERN SLAVERY STATEMENT UNDER THE MODERN SLAVERY ACT 2018 (CTH) FOR THE REPORTING PERIOD 1 JANUARY 2020 TO 31 DECEMBER 2020 Shell Energy Holdings Australia Limited has prepared this modern slavery statement in consultation with each of the following reporting entities, and is published by the following reporting entities in compliance with the Modern Slavery Act 2018 (Cth) (No. 153, 2018) (“Modern Slavery Act”):- 1) Shell Energy Holdings Australia Limited (“SEHAL”); 2) QGC Upstream Investments Pty Ltd (“QGC Upstream”); 3) QGC Midstream Investments Pty Ltd (“QGC Midstream”); and 4) ERM Power Limited (“ERM Power”), (collectively “Shell”, “our” or “we”)i Note on ERM Power: At the time this statement’s publication, ERM Power Limited will have been re- named to Shell Energy Operations Pty Ltd. However, as this statement pertains to ERM Power Limited’s structure, operations and supply chain from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020, we have maintained the previous entity name of ERM Power Limited for this statement. In addition, as ERM Power’s integration into Shell is ongoing, we have noted throughout this statement where ERM Power’s approach or processes differ from that of Shell. Finally, at the time this statement’s publication, ERM Power’s policies, for which links are listed under the “ERM Power” sub-heading in “Our values, policies & approach to human rights”, will be decommissioned; however would be available upon request as ERM has adopted the equivalent Shell policies. Introduction Shell is opposed to all forms of modern slavery. Such exploitation is against Shell’s commitment to respect human rights as set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Labour Organization 1998 Declaration of the Fundamental Principles of Rights at Work. -

Western Downs

Image courtesy of Shell's QGC business “We have a strong and diverse economy that is enhanced by the resource sector through employment, Traditional Resources - infrastructure and Western Downs improved services." The Western Downs is known as the “Queensland has the youngest coal- Paul McVeigh, Mayor Energy Capital of Queensland and is fired power fleet in Australia including Western Downs now emerging as the Energy Capital of the Kogan Creek Power Station, and an Regional Council. Australia. abundance of gas which will ensure the State has a reliable source of base load This reputation is due to strong energy for decades to come.” investment over the past 15 years by the Energy Production Industry - Ian Macfarlane, CEO, Mining is the second most productive (EPI) into large scale resource sector Queensland Resources Council industry in the Western Downs after developments in coal seam gas (CSG) As at June 2018, the Gross Regional construction, generating an output of 2 and coal. Product (GRP) of the Western Downs 2.23 billion in 2017/18. Gas and coal-fired power stations region has grown by 26.3% over a In 2017/18, the total value of local sales 2 feature prominently in the region with twelve-month period to reach $4 billion. was $759.2 million. Of these sales, oil a total of six active thermal power The resource industry paid $58 million and gas extraction was the highest, at 2 stations. in wages to 412 full time jobs (2017-18). 3 $615.7 million. Kogan Creek Power Station is one of The industry spent $136 million on In 2017/18 mining had the largest Australia's most efficient and technically goods and services purchased locally total exports by industry, generating advanced coal-fired power stations. -

Tarong Power Stations Enterprise Agreement 2018

Stanwell Corporation Limited (ABN: 37 078 848 674) and The Association of Professional Engineers, Scientists and Managers Australia and “The Automotive, Food, Metals, Engineering, Printing & Kindred Industries Union” known as the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union (the AMWU) and Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia. Electrical Division, Queensland and Northern Territory Divisional Branch and Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (Mining and Energy Division) and The Australian Municipal, Administrative, Clerical And Services Union and Australian Institute of Marine and Power Engineers’ Union of Employees, Queensland and Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation STANWELL CORPORATION LIMITED TARONG POWER STATIONS ENTERPRISE AGREEMENT 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PART 1 – PRELIMINARY ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. TITLE ................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. APPLICATION OF AGREEMENT ............................................................................................................... 6 1.3. STATEMENT OF INTENT ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. DURATION OF AGREEMENT .................................................................................................................. -

The Challenge of Institutional Governance in the National Electricity Market: a Consumer Perspective

The challenge of institutional governance in the National Electricity Market: A consumer perspective Penelope Crossley Sydney Law School The University of Sydney Page 1 My research – Adopts a commercial perspective to energy and resources law – Particular focus on renewable energy and energy storage law and policy – Interested in interdisciplinary collaborations with engineering, economics, public policy, etc. The University of Sydney Page 2 Outline of presentation – Why is the legal, governance and institutional framework of the NEM so complicated? – The institutional governance structure of the NEM – Key issues for consumers – Legal issues The University of Sydney Page 3 The ultimate source of the problem: The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (1900) The University of Sydney Page 4 s.51 of the Commonwealth Constitution Part V - Powers of the Parliament 51.The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to: - (i.) Trade and commerce […] among the States; (xx.) Foreign corporations, and trading or financial corporations formed within the limits of the Commonwealth; (xxxvii.) Matters referred to the Parliament of the Commonwealth by the Parliament or Parliaments of any State or States, but so that the law shall extend only to States by whose Parliaments the matter is referred, or which afterwards adopt the law; The University of Sydney Page 5 The rationale for the NEM – The NEM was designed to: – facilitate interstate trade; – to lower barriers to competition; – to increase regulatory certainty; and – to improve productivity, within the electricity sector as it transitioned from being dominated by large unbundled state owned monopolies to privatised corporations. -

Inquiry Into the Price of Unleaded Petrol

SHELL AUSTRALIA’S SUBMISSION TO THE AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER (ACCC) INQUIRY INTO THE PRICE OF UNLEADED PETROL CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................2 Refining and importing..........................................................................................................2 Wholesale and distribution....................................................................................................4 Retail........................................................................................................................................6 Shell submission to ACCC Petrol Price Inquiry, July 2007 Page 1 Introduction This submission addresses issues relevant to Shell under the broad subjects, “Refining and importing”, “Wholesale and distribution” and “Retail”, which are set out in the Issues Paper published by the ACCC in June 2007. However, as Shell is essentially no longer a retailer, the submission makes limited comment on the retail market. As an overarching comment, Shell believes that the Australian market for unleaded petrol is highly competitive as evidenced by: • the fact that Australian fuel, both pre and post tax, is amongst the cheapest in the OECD countries; • Shell’s profits before interest and tax in 2006 equate to 2.3 cents per litre of fuel and over the last five years have averaged around 1.8 cpl or 1.5% on a litre of petrol); and • Shell’s investment of over $1 billion in the Downstream business -

18 March 2020 the Manager Market Announcements Office Australian Securities Exchange Electronic Lodgment 2019 Annual Report

18 March 2020 The Manager Market Announcements Office Australian Securities Exchange Electronic lodgment 2019 Annual Report The attached document has been authorised for release by the Board of Viva Energy Group Limited. Julia Kagan Company Secretary Annual Report 2019 Our purpose Helping people reach their destination Viva Energy Group Limited ABN 74 626 661 032 Who we are Viva Energy is one of Australia’s leading energy companies with more than 110 years of operations in Australia. We refine, store and market specialty petroleum products across the country and we are the sole supplier of Shell fuels and lubricants in Australia. In 2019, we supplied approximately a quarter of Australia’s liquid fuel requirements to a national network of retail sites and directly to our commercial customers. We also operate a nationwide fuel supply chain, including the strategically located Geelong Refinery, an extensive import, storage and distribution infrastructure network, including a presence at over 50 airports and airfields. Our values Integrity The right thing always Responsibility Safety, environment, our communities Curiosity Be open, learn, shape our future Commitment Accountable and results focused Respect Inclusiveness, diversity, people We are proud to present our inaugural Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) 2019–2021. See page 49 for details. 01 Viva Energy Group Limited Annual Report 2019 Contents About us 04 Financial report 79 Chairman and Chief Executive Officer’s report 06 Consolidated financial statements 80 Board of Directors 08 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 85 Executive Leadership Team 10 Directors’ declaration 135 Operating and financial review 13 Independent auditor’s report 136 Sustainability 32 Disclosures 143 Remuneration report 56 Additional information 146 Directors’ report 73 Corporate directory 149 Auditor’s independence declaration 78 About this Annual Report This Annual Report contains information on the operations, activities and entities. -

Stoxx® Pacific Total Market Index

STOXX® PACIFIC TOTAL MARKET INDEX Components1 Company Supersector Country Weight (%) CSL Ltd. Health Care AU 7.79 Commonwealth Bank of Australia Banks AU 7.24 BHP GROUP LTD. Basic Resources AU 6.14 Westpac Banking Corp. Banks AU 3.91 National Australia Bank Ltd. Banks AU 3.28 Australia & New Zealand Bankin Banks AU 3.17 Wesfarmers Ltd. Retail AU 2.91 WOOLWORTHS GROUP Retail AU 2.75 Macquarie Group Ltd. Financial Services AU 2.57 Transurban Group Industrial Goods & Services AU 2.47 Telstra Corp. Ltd. Telecommunications AU 2.26 Rio Tinto Ltd. Basic Resources AU 2.13 Goodman Group Real Estate AU 1.51 Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. Basic Resources AU 1.39 Newcrest Mining Ltd. Basic Resources AU 1.37 Woodside Petroleum Ltd. Oil & Gas AU 1.23 Coles Group Retail AU 1.19 Aristocrat Leisure Ltd. Travel & Leisure AU 1.02 Brambles Ltd. Industrial Goods & Services AU 1.01 ASX Ltd. Financial Services AU 0.99 FISHER & PAYKEL HLTHCR. Health Care NZ 0.92 AMCOR Industrial Goods & Services AU 0.91 A2 MILK Food & Beverage NZ 0.84 Insurance Australia Group Ltd. Insurance AU 0.82 Sonic Healthcare Ltd. Health Care AU 0.82 SYDNEY AIRPORT Industrial Goods & Services AU 0.81 AFTERPAY Financial Services AU 0.78 SUNCORP GROUP LTD. Insurance AU 0.71 QBE Insurance Group Ltd. Insurance AU 0.70 SCENTRE GROUP Real Estate AU 0.69 AUSTRALIAN PIPELINE Oil & Gas AU 0.68 Cochlear Ltd. Health Care AU 0.67 AGL Energy Ltd. Utilities AU 0.66 DEXUS Real Estate AU 0.66 Origin Energy Ltd. -

Surat Basin Non-Resident Population Projections, 2021 to 2025

Queensland Government Statistician’s Office Surat Basin non–resident population projections, 2021 to 2025 Introduction The resource sector in regional Queensland utilises fly-in/fly-out Figure 1 Surat Basin region and drive-in/drive-out (FIFO/DIDO) workers as a source of labour supply. These non-resident workers live in the regions only while on-shift (refer to Notes, page 9). The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) official population estimates and the Queensland Government’s population projections for these areas only include residents. To support planning for population change, the Queensland Government Statistician’s Office (QGSO) publishes annual non–resident population estimates and projections for selected resource regions. This report provides a range of non–resident population projections for local government areas (LGAs) in the Surat Basin region (Figure 1), from 2021 to 2025. The projection series represent the projected non-resident populations associated with existing resource operations and future projects in the region. Projects are categorised according to their standing in the approvals pipeline, including stages of In this publication, the Surat Basin region is defined as the environmental impact statement (EIS) process, and the local government areas (LGAs) of Maranoa (R), progress towards achieving financial close. Series A is based Western Downs (R) and Toowoomba (R). on existing operations, projects under construction and approved projects that have reached financial close. Series B, C and D projections are based on projects that are at earlier stages of the approvals process. Projections in this report are derived from surveys conducted by QGSO and other sources. Data tables to supplement the report are available on the QGSO website (www.qgso.qld.gov.au).