Rabbi Kulwin, Yom Kippur AM Sermon 5774 (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELEAZAR S. FERNANDEZ Professor Of

_______________________________________________________________________________ ELEAZAR S. FERNANDEZ Professor of Constructive Theology United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities 3000 Fifth Street Northwest New Brighton, Minnesota 55112, U.S.A. Tel. (651) 255-6131 Fax. (651) 633-4315 E-Mail [email protected] President, Union Theological Seminary, Philippines Sampaloc 1, Dasmarinas City, Cavite, Philippines E-Mail: [email protected] Mobile phone: 63-917-758-7715 _______________________________________________________________________________ PROFESSIONAL PREPARATION VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY, Nashville, Tennessee, U.S.A. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD.) Major: Philosophical and Systematic Theology Minor: New Testament Date : Spring 1993 PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.A. Master of Theology in Social Ethics (ThM), June 1985 UNION THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, Cavite, Philippines Master of Divinity (MDiv), March 1981 Master's Thesis: Toward a Theology of Development Honors: Cum Laude PHILIPPINE CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY, Cavite, Philippines Bachelor of Arts in Psychology (BA), 1980 College Honor/University Presidential Scholarship THE COLLEGE OF MAASIN, Maasin, Southern Leyte, Philippines Associate in Arts, 1975 Scholar, Congressman Nicanor Yñiguez Scholarship PROFESSIONAL WORK EXPERIENCE President and Academic Dean, Union Theological Seminary, Philippines, June 1, 2013 – Present. Professor of Constructive Theology, United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities, New Brighton, Minnesota, July 1993-Present. Guest/Mentor -

Eleazar Wheelock and His Native American Scholars, 1740-1800

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1999 Crossing Cultural Chasms: Eleazar Wheelock and His Native American Scholars, 1740-1800 Catherine M. Harper College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Other Education Commons Recommended Citation Harper, Catherine M., "Crossing Cultural Chasms: Eleazar Wheelock and His Native American Scholars, 1740-1800" (1999). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626224. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-0w7z-vw34 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CROSSING CULTURAL CHASMS: ELEAZAR WHEELOCK AND HIS NATIVE AMERICAN SCHOLARS, 1740-1800 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Catherine M. Harper 1999 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Catherine M.|Harper Approved, January 1999: A xw jZ James Axtell James Whittenfmrg Kris Lane, Latin American History TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 2 CHAPTER ONE: THE TEACHER 10 CHAPTER TWO: THE STUDENTS 28 CONCLUSION 51 BIBLIOGRAPHY 63 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my thanks to Professor James Axtell for his thoughtful criticism and patient guidance through the research and writing stages of this essay. -

THE PRIESTLY COVENANT – Session Five

THE COVENANT: A Lenten Journey Curriculum THE PRIESTLY COVENANT – Session Five Leader’s Opening Remarks Our covenant journey has taken us to Eden, where a broken promise activates the genesis of redemption. Next, we went by boat with Noah, where God re-created the world as the stage upon which the story of God’s grace and redemption would play out. Then despite Abraham and Sarah’s shortcomings, God used them to secure the innumerable seed of blessing that God had in store for the world. Last week, we made a turn as we Laws, or standards that God would set to define how one should live in relationship with God and with others. 57 THE COVENANT: A Lenten Journey Curriculum Today, we will look again at Moses and this time, also his brother, Aaron, his nephew, Eleazar, and Eleazar’s son, Phinehas. This journey will reveal the importance of succession. The priestly covenant is a covenant of peace. But it starts out as anything but peaceful… Remember Moses’ reluctance to do what God had for him? He stuttered, and insisted that he wasn’t capable of doing all that God was calling him to do. So, God relented and gave Moses his brother, Aaron as an assurance that Moses had all that was needed to help free the Israelites from Pharaoh. A series of plagues and the death of Pharaoh’s son later, and Moses, Aaron, and all of the Israelites, crossed the Red Sea, and the enemy was defeated! But it still was not peaceful! 58 THE COVENANT: A Lenten Journey Curriculum The Israelites received the law, but the idolatry of Israel angered God and God denied the Israelites the peace that God had for them. -

10 So Moses and Aaron Went to Pharaoh and Did Just As the Lord Commanded

Today’s Scripture Reading Exodus 6:14-7:13 14 These are the heads of their fathers' houses: the sons of Reuben, the firstborn of Israel: Hanoch, Pallu, Hezron, and Carmi; these are the clans of Reuben. 15 The sons of Simeon: Jemuel, Jamin, Ohad, Jachin, Zohar, and Shaul, the son of a Canaanite woman; these are the clans of Simeon. 16 These are the names of the sons of Levi according to their generations: Gershon, Kohath, and Merari, the years of the life of Levi being 137 years. 17 The sons of Gershon: Libni and Shimei, by their clans. 18 The sons of Kohath: Amram, Izhar, Hebron, and Uzziel, the years of the life of Kohath being 133 years. ! 6:14-7:13 19 The sons of Merari: Mahli and Mushi. These are the clans of the Levites according to their generations. 20 Amram took as his wife Jochebed his father's sister, and she bore him Aaron and Moses, the years of the life of Amram being 137 years. 21 The sons of Izhar: Korah, Nepheg, and Zichri. 22 The sons of Uzziel: Mishael, Elzaphan, and Sithri. 23 Aaron took as his wife Elisheba, the daughter of Amminadab and the sister of Nahshon, and she bore him Nadab, Abihu, Eleazar, and Ithamar. 24 The sons of Korah: Assir, Elkanah, and Abiasaph; these are the clans of the Korahites. ! 6:14-7:13 25 Eleazar, Aaron's son, took as his wife one of the daughters of Putiel, and she bore him Phinehas. These are the heads of the fathers' houses of the Levites by their clans. -

The Aaronic Priesthood Exodus 28:1

THE AARONIC PRIESTHOOD EXODUS 28:1 Man has an inherent knowledge of God (Rom. 1:18-32) and sinfulness (Rom. 2:14-15) and it seems every religion has some sort of priesthood to repre- sent man to God. In the case of Judaism, it was the Aaronic Priesthood. Romans 1:18–19 18For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men who suppress the truth in unrighteous- ness, 19because that which is known about God is evident within them; for God made it evident to them. Romans 2:14–15 14For when Gentiles who do not have the Law do instinctively the things of the Law, these, not having the Law, are a law to themselves, 15in that they show the work of the Law written in their hearts, their conscience bear- ing witness and their thoughts alternately accusing or else defending them, In Exodus 27:21, we noted the first hint of the appointment of Aaron and his sons to be the priests of Yahweh. In Exodus 28:1, the appointment was offi- cially proclaimed. Exodus 28:1 1“Then bring near to yourself Aaron your brother, and his sons with ,to Me—Aaron [כָּהַן] him, from among the sons of Israel, to minister as priest Nadab and Abihu, Eleazar and Ithamar, Aaron’s sons. and it refers to the כֹּהֵן is not the word for priest; that word is כָּהַן The word means to ,כָּהַן ,position of priest as mediator between God and man. This word act or to serve as a priest, hence, the NASB translates it to “minister as priest.” One is the noun and one is the verb. -

Aminadab in •Œthe Birth-Markâ•Š

Aminadab in "The Birth-lTIark": The NalTIeAgain JOHN o. REES The name Aminadab, which Hawthorne gave to the scientist Ayl- mer's clod-like assistant in "The Birth-mark," has intrigued a number of commentators. They explain Hawthorne's choosing this particular name in two sharply different ways, and within each camp there is further disagreement on what the supposed choice implies, about both Aminadab and his master. Yet these interpretations have all been notable for th~ir heavily labored ingenuity; and none of them, I think has been sound. I want to argue here that both accounts of the name's origin are unconvincing in themselves, and that both have fostered exaggeration of a minor character's importance, and hence distortion of the overall meaning of "The Birth-mark." And finally, I want to suggest at least one other possible source for Hawthorne's Aminadab, a source consistent with his pointedly simple nature and role in the tale. The first, larger group regards the character as a namesake figure, traceable to the author's Bible reading. 1 Aminadab, which in Hebrew means "my people are willing," appears twelve times in the Old IW.R. Thompson, "Aminadab in Hawthorne's 'The Birth-Mark,'" MLN, 70 (1955), 413-15; Roy R. Male, Hawthorne's Tragic Vision (1957; rpt. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1964), pp. 81-82; Jean Normand, Nathaniel Hawthorne: An Approach to an Analysis of Artistic Creation, trans. from 1st ed. by Derek Coltman (1964; rpt. Cleveland and London: Case Western Reserve Univ. Press, 1970), p. 379; Hugo McPherson, Hawthorne as Myth-Maker: A Study in Imagination (Toronto: Univ. -

THE DEVIATION of AARON, ELEAZAR, and ITHAMAR EXCUSED Leviticus 10:12-20

Thirteenth Message, Lev. 10:12-20 Page 1 THIRTEENTH MESSAGE: THE DEVIATION OF AARON, ELEAZAR, AND ITHAMAR EXCUSED Leviticus 10:12-20 Introduction The events of these verses occurred when Moses and other family members returned from mourning over Nadab and Abihu. It was the custom in those days to bury deceased people almost immediately after their deaths, because of the rapidity with which bodies began to decay in the warm climate. As soon as Moses returned, he instructed Aaron, Nadab, and Abihu to complete their part of the offerings that had been offered by the people just before Nadab and Abihu sinned. The fat of the offerings had already been placed on the altar for roasting (Lev. 9:19-20), but the priests had not eaten their portions of those offerings. The message came as a response to a deviation that Aaron and his two remaining sons had already committed from the prescribed ceremony of the sin-offering while Moses was away at the funeral. Moses was deeply disturbed by their deviation, because Nadab and Abihu had already suffered so severely for offering an unauthorized offering. However, Aaron’s response to Moses’ concern led both Moses to agree that Jehovah would excuse the deviation because of the circumstances of that day. Jehovah showed His agreement by not killing Eleazar and Ithamar as He had Nadab and Abihu. The difference in the way the two situations were handled shows that certain circumstances could allow for a departure from the strict fulfillment of every detail of the offering ceremonies. The difference between the sin of Nadab and Abihu and the deviation of Aaron, Eleazar, and Ithamar was the intent of their hearts. -

The House of Annas (01-May-20)

CGG Weekly: The House of Annas (01-May-20) "There is no safety for honest men but by believing all possible evil of evil men." —Edmund Burke 01-May-20 The House of Annas The evangelist Luke writes in Luke 3:1-2: "Now in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judea, . while Annas and Caiaphas were high priests, the word of God came to John the son of Zacharias in the wilderness." We know what happened at the end of this story: Pilate condemned Jesus Christ to crucifixion on Passover day in AD 31. But how much do we know about the people who conspired to put Him to death, Annas and Caiaphas, who were high priests at the time? These two men were Sadducees. The Sadducees did not leave any written records themselves, but The Jewish Encyclopedia summarizes their views and principles: The Sadducees represented the powerful and wealthy, and their interests focused on the here and now. They tended to be astute politicians. They conducted their lives to enrich themselves and protect their positions of power. Page 1 of 6 CGG Weekly: The House of Annas (01-May-20) The Sadducees considered only the five books of Moses to be authoritative. In rejecting the prophets, they did not believe in a resurrection (Acts 23:8). The same verse says they did not believe in angels or demons either. They judged harshly; mercy does not seem to have part of their character. Unlike the Pharisees, who maintained that the Oral Law provided for a correct interpretation of God's Word, the Sadducees believed only in the written law and a literal interpretation of it. -

The Maccabean Revolt

THE MARION COUNTY MANNA PROJECT offers a Printer Friendly Summary of THE MACCABEAN REVOLT Question: "What happened in the Maccabean Revolt?" Answer: The Maccabean Revolt (1) was a Jewish rebellion against their Greek/Syrian oppressors in Israel, c. 167—160 BC, as well as a rejection of Hellenistic compromises in worship. The history of the Maccabean Revolt is found in 1 & 2 Maccabees (2) and in the writings of Josephus. The origin of Hanukkah (3) is traced back to the Maccabean Revolt. First, some background on the events leading up to the Maccabean Revolt. The Old Testament (4) closes with the book of Malachi (5), covering events to roughly 400 BC. After that, Alexander the Great (6) all but conquers the known civilized world and dies in 323 BC. His empire is distributed to his four generals who consolidate their territory and establish their dynasties. Ptolemy, one of his generals, ruled in Egypt. Seleucus, another of his generals, ruled over territory that included Syria. These generals founded dynasties that were often at war with each other. Israel (7), located between the two kingdoms, occupied a precarious position. Ptolemaic rule of Israel (Palestine) was tolerant of Jewish religious practices. However, the Seleucid Empire (8) eventually won control of the area and began to curtail Jewish religious practices. In 175 BC, Antiochus IV (9) came to power. He chose for himself the name Antiochus Epiphanes, which means “god manifest.” He began to persecute the Jews in earnest. He outlawed Jewish reli- gious practices (including the observance of kosher food laws) and ordered the worship of the Greek god Zeus. -

The Hannah Figure in the Babylonian Talmud (Berakhot 31A-32B)

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2010 Identification with a woman? The hannah figure in the babylonian talmud Plietzsch, Susanne DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110222043.3.215 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-45759 Book Section Published Version Originally published at: Plietzsch, Susanne (2010). Identification with a woman? The hannah figure in the babylonian talmud. In: Xeravits, Géza G; Dušek, Jan. The stranger in ancient and mediaeval Jewish tradition. Papers read at the first Meeting of the JBSCE, Piliscsaba, 2009. Berlin: De Gruyter, 215-227. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110222043.3.215 Identification with a Woman? The Hannah Figure in the Babylonian Talmud (Berakhot 31a‐32b) SUSANNE PLIETZSCH At the synagogue service of the first day of Rosh Hashana two Biblical readings are concerned with birth. The Torah reading of Genesis 21 contains the birth of Isaac, the son of Sarah and Abraham. The first two chapters of 1Samuel are the Haftara (reading from the prophets) of the day. They tell us the story about the childless Hannah who finally gave birth to Samuel. Since Rosh Hashana is, according to the rabbinic tradi‐ tion, not only the beginning of the year but also the beginning of crea‐ tion, the liturgical connection between both birth stories implies an analogy between the birth of Isaac and Samuel and the creation of the world. The strong presence of both pregnancy and birth in the Rosh Ha‐ shana service is impressing. -

1) the Centrality of Worshipping God

1 Chronicles 9:1-34 9 So all Israel was recorded in genealogies, and these are written in the Book of the Kings of Israel. And Judah was taken into exile in Babylon because of their breach of faith. 2 Now the first to dwell again in their possessions in their cities were Israel, the priests, the Levites, and the temple servants. 3 And some of the people of Judah, Benjamin, Ephraim, and Manasseh lived in Jerusalem: 4 Uthai the son of Ammihud, son of Omri, son of Imri, son of Bani, from the sons of Perez the son of Judah.5 And of the Shilonites: Asaiah the firstborn, and his sons. 6 Of the sons of Zerah: Jeuel and their kinsmen, 690. I went down 7 Of the Benjaminites: Sallu the son of Meshullam, son of Hodaviah, son of Hassenuah, 8 Ibneiah the son of Jeroham, Elah the son of Uzzi, son of Michri, and Meshullam the son of Shephatiah, son of Reuel, son of Ibnijah; 9 and their kinsmen according to their generations, 956. All these were heads of fathers' houses according to their fathers' houses. tains. 10 Of the priests: Jedaiah, Jehoiarib, Jachin, 11 and Azariah the son of Hilkiah, son of Meshullam, son of Zadok, son of Meraioth, son of Ahitub, the chief officer of the house of God; 12 and Adaiah the son of Jeroham, son of Pashhur, son of Malchijah, and Maasai the son of Adiel, son of Jahzerah, son of Meshullam, son of Meshillemith, son of Immer; 13 besides their kinsmen, heads of their fathers' houses, 1,760, mighty men for the work of the service of the house of God. -

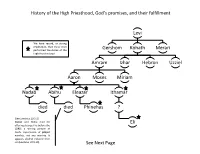

Eli's Failure and Zadok's Success

History of the High Priesthood, God’s promises, and their fulfillment Levi We have record, or strong implication, that these men performed the duties of the Gershom Kohath Merari High Priest in Israel Amram Izhar Hebron Uzziel Aaron Moses Miriam Nadab Abihu Eleazar Ithamar died died Phinehas ? (See Leviticus 10:1-2) Nadab and Abihu died for Eli offering strange fire before the LORD; a stirring picture of God’s expectation of proper worship, not any worship. It appears alcohol induced their sin (Leviticus 10:9-10) See Next Page History of the High Priesthood, God’s promises, and their fulfillment Eli was God’s High Priest at the end of Nadab Abihu Eleazar Ithamar the judges. Due to Eli and his sons’ rebellion, God promised that (1) there would never be an old man in Eli’s household and (2) The family would (See Numbers 25:11) Phinehas ? be removed from the Priesthood (1 Perpetual priesthood first Samuel 2:31-35) promised to Phinehas for his zeal against sin. Was the priest Abishua Eli when Israel entered the promised land (Joshua 22) Bukki Hophni Phinehas 1 Samuel 14:3 records the lineage of Phinehas Uzzi Ichabod Ahitub Killed by Doeg the Edomite at the We have record, or strong command of Saul, because he implication, that these men Zerahaiah Ahiah helped David flee (1 Samuel 21-22) performed the duties of the High Priest in Israel Meraioth ? (See 1 Samuel 22:20; 1 Kings 1:7; 2:26-27) High Priest during the reign of David with Zadok. Fled to David after the death of his Amariah Ahimelech father Ahimelech.