Arxiv:1908.07394V3 [Astro-Ph.HE] 16 Apr 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relativistic Generation of Vortex and Magnetic Fielda) S

PHYSICS OF PLASMAS 18, 055701 (2011) Relativistic generation of vortex and magnetic fielda) S. M. Mahajan1,b) and Z. Yoshida2 1Institute for Fusion Studies, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, USA 2Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Chiba 277-8561, Japan (Received 24 November 2010; accepted 1 February 2011; published online 8 April 2011) The implications of the recently demonstrated relativistic mechanism for generating generalized vorticity in purely ideal dynamics [Mahajan and Yoshida, Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 095005 (2010)] are worked out. The said mechanism has its origin in the space-time distortion caused by the demands of special relativity; these distortions break the topological constraint (conservation of generalized helicity) forbidding the emergence of magnetic field (a generalized vorticity) in an ideal nonrelativistic dynamics. After delineating the steps in the “evolution” of vortex dynamics, as the physical system goes from a nonrelativistic to a relativistically fast and hot plasma, a simple theory is developed to disentangle the two distinct components comprising the generalized vorticity—the magnetic field and the thermal-kinetic vorticity. The “strength” of the new universal mechanism is, then, estimated for a few representative cases; in particular, the level of seed fields, created in the cosmic setting of the early hot universe filled with relativistic particle–antiparticle pairs (up to the end of the electron–positron era), are computed. Possible applications of the mechanism in intense laser produced plasmas are also explored. It is suggested that highly relativistic laser plasma could provide a laboratory for testing the essence of the relativistic drive. -

Vortices and Flux Ropes in Electron MHD Plasmas I

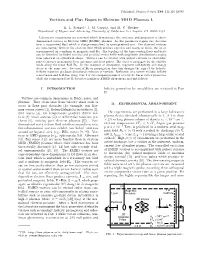

Published, Physica Scripta T84, 112-116 (2000) Vortices and Flux Ropes in Electron MHD Plasmas I. R. L. Stenzel,∗ J. M. Urrutia, and M. C. Griskey Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1547 Laboratory experiments are reviewed which demonstrate the existence and properties of three- dimensional vortices in Electron MHD (EMHD) plasmas. In this parameter regime the electrons form a magnetized fluid which is charge-neutralized by unmagnetized ions. The observed vortices are time-varying flows in the electron fluid which produce currents and magnetic fields, the latter superimposed on a uniform dc magnetic field B0. The topology of the time-varying flows and fields can be described by linked toroidal and poloidal vector fields with amplitude distributions ranging from spherical to cylindrical shape. Vortices can be excited with pulsed currents to electrodes, pulsed currents in magnetic loop antennas, and heat pulses. The vortices propagate in the whistler mode along the mean field B0. In the presence of dissipation, magnetic self-helicity and energy decay at the same rate. Reversal of B0 or propagation direction changes the sign of the helicity. Helicity injection produces directional emission of vortices. Reflection of a vortex violates helicity conservation and field-line tying. Part I of two companion papers reviews the linear vortex properties while the companion Part II describes nonlinear EMHD phenomena and instabilities. I. INTRODUCTION helicity generation by instabiliites are reviewed in Part II. Vortices are common phenomena in fluids, gases, and plasmas. They often arise from velocity shear such as II. EXPERIMENTAL ARRANGEMENT occur in flows past obstacles (for example, von Kar- man vortex streets [1], Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities [2], drift waves [3], ion temperature gradient driven vor- The experiments are performed in a large laboratory tices [4], black auroras [5]) or differential rotations (cy- plasma device sketched schematically in 1. -

3-Dimensional Evolution of a Magnetic Flux Tube Emerging Into the Solar Atmosphere T. Magara

NATO Advanced Research Workshop 3-dimensional Evolution of a Magnetic Flux Tube Emerging into the Solar Atmosphere T. Magara (Montana State University, USA) September 17, 2002 (Budapest, Hungary) We focus on three solar regions. Each region has a different type of background gas layers with which magnetic field interacts. • The corona (over the photosphere) ... low-density background gas layers • The photosphere ... abrupt change of background gas layers • The convection zone ... high-density background gas layers Corona : Because the background gas pressure is weaker than mag- netic pressure, the magnetic field continues to expand outward. (magnetic-field dominant region) A well-developed magnetic structure is formed. This structure is macroscopically static (force-free), however • outermost area... dynamic (solar wind) • prominence area... mass motion along B • coronal loops... mass motion along B Sometimes explosive events (relaxation of magnetic energy) happen in such a well-developed structure. These events are • flares (produce high energy particles & electromagnetic waves) • prominence eruptions (cool material erupts and disappears) • coronal mass ejections (large amount of mass is ejected into IP) To study various coronal processes, we initially assume a skeleton of magnetic field which provides a model of well-developed coronal structure. Then we in- vestigate its stability and evolution at both linear and nonlinear phases. Input stage: impose various type of perturbations to the system according to the primary purpose of studies -

Magnetic Helicity Reversal in the Corona at Small Plasma Beta

The Astrophysical Journal, 869:2 (9pp), 2018 December 10 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aae97a Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj pab v. 21/02/18 Magnetic Helicity Reversal in the Corona at Small Plasma Beta Philippe-A. Bourdin1, , Nishant K. Singh2;3, , Axel Brandenburg3;4;5;6, 1 Space Research Institute, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Schmiedlstr. 6, A-8042 Graz, Austria 2 Max-Planck-Institut f¨urSonnensystemforschung, Justus-von-Liebig-Weg 3, D-37077 G¨ottingen,Germany 3 Nordita, KTH Royal Institute of Technology and Stockholm University, Roslagstullsbacken 23, SE-10691 Stockholm, Sweden 4 JILA and Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80303, USA 5 Department of Astronomy, AlbaNova University Center, Stockholm University, SE-10691 Stockholm, Sweden and 6 Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80303, USA Received 2018 April 11; revised 2018 October 17; accepted 2018 October 17; published 2018 December 5 Abstract Solar and stellar dynamos shed small-scale and large-scale magnetic helicity of opposite signs. However, solar wind observations and simulations have shown that some distance above the dynamo both the small- scale and large-scale magnetic helicities have reversed signs. With realistic simulations of the solar corona above an active region now being available, we have access to the magnetic field and current density along coronal loops. We show that a sign reversal in the horizontal averages of the magnetic helicity occurs when the local maximum of the plasma beta drops below unity and the field becomes nearly fully force free. Hence, this reversal is expected to occur well within the solar corona and would not directly be accessible to in-situ measurements with the Parker Solar Probe or SolarOrbiter. -

Novel Methods to Determine and Use the Magnetic Vector Potential in Numerical General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamics

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 8-14-2018 Novel Methods to Determine and Use the Magnetic Vector Potential in Numerical General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamics Zachary J. Silberman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Silberman, Zachary J., "Novel Methods to Determine and Use the Magnetic Vector Potential in Numerical General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamics" (2018). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rochester Institute of Technology Ph.D. Dissertation Novel Methods to Determine and Use the Magnetic Vector Potential in Numerical General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamics Author: Advisor: Zachary J. Silberman Joshua Faber A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Astrophysical Sciences and Technology School of Physics and Astronomy College of Science August 14, 2018 Rochester Institute of Technology Ph.D. Dissertation Novel Methods to Determine and Use the Magnetic Vector Potential in Numerical General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamics Author: Advisor: Zachary J. Silberman Joshua Faber A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Astrophysical Sciences and Technology School of Physics and Astronomy College of Science Approved by Dr. Andrew Robinson Date Director, Astrophysical Sciences and Technology Certificate of Approval Astrophysical Sciences and Technology R·I·T College of Science Rochester, NY, USA The Ph.D. Dissertation of Zachary J. -

Inverse Cascade Magnetic Helicity

J. Fluid Mech. (1975), vol. 68, part 4, pp. 769-778 769 Printed in Great Britain . Possibility of an inverse cascade of magnetic helicity in magnetohydrodynamic turbulence By U. FRISCH, A. POUQUET, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Observatoire de Nice, France J. LBORAT AND A. MAZURE Universite Paris VII; Observatoire de Meudon, France https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms (Received 2 November 1973 and in revised form 10 October 1974) Some of the consequences of the conservation of magnetic helicity sa. bd3r (a = vector potential of magnetic field b) for incompressible three-dimensional turbulent MHD flows are investigated. Absolute equilibrium spectra for inviscid infinitely conducting flows truncated at lower and upper wavenumbers k,,, and k,,, are obtained. When the total magnetic helicity approaches an upper limit given by the total energy (kinetic plus magnetic) divided by the spectra of magnetic energy and helicity are strongly peaked near kmin;in addition, when the cross-correlations between the , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at velocity and magnetic fields are small, the magnetic energy density near kmin greatly exceeds the kinetic energy density. Several arguments are presented in favour of the existence of inverse cascades of magnetic helicity towards small wavenumbers leading to the generation of large-scale magnetic energy. 28 Feb 2018 at 23:14:04 1. Introduction , on It is known that turbulent flows which are not statistically invariant under plane reflexions may be important for the generation of magnetic fields; for example, Steenbeck, Krause & Radler (1966) have shown within the framework of the kinematic dynamo problem (prescribed velocity fields) that in helical flows, i.e. -

The Transport of Relative Canonical Helicity

MANUSCRIPT (to be published in Phys. Plasmas) JULY 2012 The transport of relative canonical helicity S. You Aeronautics & Astronautics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA The evolution of relative canonical helicity is examined in the two-fluid magnetohydrodynamic formalism. Canonical helicity is defined here as the helicity of the plasma species’ canonical momentum. The species’ canonical helicity are coupled together and can be converted from one into the other while the total gauge-invariant relative canonical helicity remains globally invariant. The conversion is driven by enthalpy differences at a surface common to ion and electron canonical flux tubes. The model provides an explanation for why the threshold for bifurcation in counter-helicity merging depends on the size parameter. The size parameter determines whether magnetic helicity annihilation channels enthalpy into the magnetic flux tube or into the vorticity flow tube components of the canonical flux tube. The transport of relative canonical helicity constrains the interaction between plasma flows and magnetic fields, and provides a more general framework for driving flows and currents from enthalpy or inductive boundary conditions. I. INTRODUCTION Previous treatments of canonical helicity—also known as generalized vorticity 1, self-helicity 2, generalized helicity 3, or fluid helicity 4—concluded that the canonical helicities of each species were invariant, independent from each other. Assuming closed canonical circulation flux tubes inside singly-connected volumes, and arguing for selective decay arguments in the presence of dissipation, it was shown that canonical helicity is a constant of the system stronger than magnetofluid energy. Generalized relaxation theories could therefore minimize magnetofluid energy for a given canonical helicity and derive stationary relaxed states. -

Magnetic Helicity Content in Solar Wind Flux Ropes

Universal Heliophysical Processes Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 257, 2008 c 2009 International Astronomical Union N. Gopalswamy & D.F. Webb, eds. doi:10.1017/S1743921309029603 Magnetic helicity content in solar wind flux ropes Sergio Dasso Instituto de Astronom´ıa y F´ısica del Espacio (IAFE), CONICET-UBA and Departamento de F´ısica, FCEN-UBA, Buenos Aires, Argentina email: [email protected] Abstract. Magnetic helicity (H) is an ideal magnetohydrodynamical (MHD) invariant that quantifies the twist and linkage of magnetic field lines. In magnetofluids with low resistivity, H decays much less than the energy, and it is almost conserved during times shorter than the global diffusion timescale. The extended solar corona (i.e., the heliosphere) is one of the physical sce- narios where H is expected to be conserved. The amount of H injected through the photospheric level can be reorganized in the corona, and finally ejected in flux ropes to the interplanetary medium. Thus, coronal mass ejections can appear as magnetic clouds (MCs), which are huge twisted flux tubes that transport large amounts of H through the solar wind. The content of H depends on the global configuration of the structure, then, one of the main difficulties to estimate it from single spacecraft in situ observations (one point - multiple times) is that a single spacecraft can only observe a linear (one dimensional) cut of the MC global structure. Another serious difficulty is the intrinsic mixing between its spatial shape and its time evolution that occurs during the observation period. However, using some simple assumptions supported by observations, the global shape of some MCs can be unveiled, and the associated H and mag- netic fluxes (F ) can be estimated. -

THE ROLE of MAGNETIC HELICITY in the STRUCTURE and HEATING of the SUN's CORONA Kalman J. Knizhnik

THE ROLE OF MAGNETIC HELICITY IN THE STRUCTURE AND HEATING OF THE SUN’S CORONA by Kalman J. Knizhnik A dissertation submitted to The Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Baltimore, Maryland June, 2016 c Kalman J. Knizhnik 2016 All rights reserved Abstract Two of the most important and interesting features of the solar atmosphere are its hot, smooth coronal loops and the significant concentrations of magnetic shear, known as filament channels, that reside above photospheric polarity inversion lines (PILs; locations where the line-of-sight component of the photospheric magnetic field changes sign). The shear that is inherent in filament channels represents magnetic helicity, a topological quantity describing the amount of linkage in the magnetic field. The smoothness of the coronal loops, on the other hand, indicates an apparent lack of magnetic helicity in the rest of the corona. At the same time, models that attempt to explain the high temperatures observed in these coronal loops require magnetic energy, in the form of twist, to be injected at the photospheric level, after which this energy is converted to heat through the process of magnetic reconnection. In addition to magnetic energy, the twist that is injected at the photospheric level also represents magnetic helicity. Unlike magnetic energy, magnetic helicity is conserved under reconnection, and is consequently expected to accumulate and be observed in the corona. However, filament channels, rather than the coronal loops, are the lo- cations in the corona where magnetic helicity is observed, and it manifests itself in the form of shear, rather than twist. -

Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics Evolution of Magnetic Helicity Under

Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics (2002) 9: 139–147 Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics c European Geophysical Society 2002 Evolution of magnetic helicity under kinetic magnetic reconnection: Part II B 6= 0 reconnection T. Wiegelmann1,2 and J. Buchner¨ 2 1 School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews, KY16 9SS, United Kingdom 2Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ Aeronomie, Max-Planck-Str. 2, 37191 Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany Received: 1 February 2001 – Revised: 10 April 2001 – Accepted: 17 April 2001 Abstract. We investigate the evolution of magnetic helicity field and changes in topology are not possible. Thus, mag- under kinetic magnetic reconnection in thin current sheets. netic reconnection cannot occur and the magnetic helicity is We use Harris sheet equilibria and superimpose an external conserved exactly (e.g. Woltjer, 1960). magnetic guide field. Consequently, the classical 2D mag- A strictly ideal plasma, however, does not exist in nature netic neutral line becomes a field line here, causing a B 6= 0 and thus, magnetic reconnection is possible in principle. It reconnection. While without a guide field, the Hall effect has been conjectured by Taylor (1974) that the helicity is still leads to a quadrupolar structure in the perpendicular mag- approximately conserved during the relaxation processes in- netic field and the helicity density, this effect vanishes in the volving magnetic reconnection. Later, Berger (1984) proved B 6= 0 reconnection. The reason is that electrons are mag- that the total helicity is decreasing on a longer time scale than netized in the guide field and the Hall current does not occur. the magnetic energy. -

Helicity and Celestial Magnetism Rspa.Royalsocietypublishing.Org H

Helicity and Celestial Magnetism rspa.royalsocietypublishing.org H. K. Moffatt1 1 Research Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge, Article submitted to journal Wilberforce Road, Cambridge CB3 0WA, UK This informal article discusses the central role of Subject Areas: magnetic and kinetic helicity in relation to the geophysics, astrophysics, dynamo evolution of magnetic fields in geophysical and theory astrophysical contexts. It is argued that the very existence of magnetic fields of the intensity and Keywords: scale observed is attributable in large part to the magnetic fields, chirality, chirality of the background turbulence or random- magnetostrophic, magnetic relaxation wave field of flow, the simplest measure of this chirality being non-vanishing helicity. Such flows are responsible for the generation of large-scale Author for correspondence: magnetic fields which themselves exhibit magnetic Insert corresponding author name helicity. In the geophysical context, the turbulence e-mail: [email protected] has a ‘magnetostrophic’ character in which the force balance is primarily that between buoyancy forces, Coriolis forces and Lorentz forces associated with the dynamo-generated magnetic field; the dominant nonlinearity here arises from the convective transport of buoyant elements erupting from the ‘mushy zone’ at the inner core boundary. At the opposite extreme, in a highly conducting low-density plasma, the near-invariance of magnetic field topology (and of associated helicity) presents the challenging problem of ‘magnetic relaxation under topological constraints’, of central importance both in astrophysical contexts and in controlled-fusion plasma dynamics. These problems are reviewed and open issues, particularly concerning saturation mechanisms, are reconsidered. -

Proceedings of the Fifth Symposium on the Physics and Technology of Compact Toroids November 16-18, 1982 Mastffl

NOTICE PORTIONS OF THSS REPORT ARE ILLEGIBLE. It has been reproduced fron the best available copy to permit the broadest possible availability. CONF MSNW COUF-821124- DE85 000450 Proceedings of the Fifth Symposium on the Physics and Technology of Compact Toroids DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsi- bility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Refer- ence herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recom- mendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, The vlews and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES NORTHWEST, INC. November 16-18, 1982 MASTFfl A.L. Hoffman R.D. Milroy DISTRIBUTION OF THIS DSCCMfflT "IS'lMllitW January 1983 Sage Agenda vii Review of the Fifth Syaposiua on the Physics ix and Technology of Coapact Toroids FRC FDRMKTXCN "Numerical Modeling of FRC Translation on FRX-C" 1 (W.T. Armstrong and R.D. Milroy) "Laser Heating of Field-Reversed-Configurations" 4 (R.S. Carson and G.C. Vlases) "Flux Trapping During Fiald Reversal in 8 a Field Reversed Theta Pinch" (R.D.