Exploded Dream: Desegregation in the Memphis City Schools Daniel Kiel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda.NET Shelby County Board of Education

e|agenda.NET Shelby County Board of Education Shelby County Board of Education Business Meeting Agenda - December 20, 2011 Shelby County Board of Education Business Meeting Agenda - December 20, 2011 I. Roll Call II. Pledge of Allegiance III. Moment of Silent Meditation IV. Approval of Agenda 1. Approval of Agenda V. Recognitions 2. Spotlight on the Arts 3. Recognition of MEA Holiday Card Contest Winners 4. Recognition of Milken Award Recipient, Meah King 5. Recognition of Fred Johnson VI. Board Business Affairs A. Approval of Minutes 6. Approval of Minutes from the Special Called Board Business Meeting - November 22, 2011 Attachment: 11.22.11 Special Called Minutes.pdf 7. Approval of Minutes from the November 29, 2011 Business Meeting Attachment: 11.29.11 Board Minutes.pdf 8. Approval of Minutes from the Board Work Session Minutes from December 13, 2011 Attachment: BWS Minutes - 12.13.11.pdf Page 1 of 234 B. Other 9. Request from Collierville High School PTSA and SGA Attachment: CHSsignRequest.pdf Attachment: SCSPolicy1007Naming of Schools and School Facilities.pdf Attachment: CHSMap.pdf 10. Board Self-Evaluations: Memphis City Schools and Shelby County Schools Attachment: Shelby County Board Evaluation Results2011.pdf Attachment: Previous MCS Board Operations Policy -1.7012 Board Self- Evaluation and Planning.pdf Attachment: MCS Board Self-Evaluation.pdf Attachment: MCS Board Self Evaluation Summary and Results 2010 and 2011.pdf 11. NSBA 2012 Conference Attachment: SCS Policy 0017.pdf Attachment: NSBA2012.pdf VII. Reports A. Transition Planning Commission 12. Transition Planning Commission Report - December B. Chairman 13. Chairman's Report C. Ad Hoc Committee Board Training 14. -

History Happenings

History Happenings The University of Memphis Fall 2005 History Happenings An annual newsletter published by The University of Memphis Department of History Janann M. Sherman Chair Table of Contents James Blythe Graduate Coordinator Greetings from the Chair page 3 Beverly Bond Retirement Tribute page 4 Walter R. (Bob) Brown Where are They Now? page 5 Director, Undergraduate Studies History Day Update page 6 Margaret M. Caffrey Staff Happenings page 7 James Chumney Postcard from Egypt page 8 Charles W. Crawford Awards and Kudos page 9 Director, Oral History Research Offi ce Faculty Happenings page 10 Maurice Crouse A Tribute to Teachers page 16 Douglas W. Cupples Teachers in the News page 17 Guiomar Duenas-Vargas Graduate Happenings page 18 James E. Fickle GAAAH Conference page 22 Robert Frankle Dissertations and A.B.D. Progress page 23 Aram Goudsouzian Undergraduate Happenings page 24 Robert Gudmestad Phi Alpha Theta Update page 25 Joseph Hawes Back to School Night page 27 Jonathan Judaken Abraham D. Kriegel Dennis Laumann Kevin W. Martin Kell Mitchell, Jr. D'Ann Penner C. Edward Skeen Arwin Smallwood Stephen Stein Lung-Kee Sun Daniel Unowsky Department of History Staff On the Cover: Karen Bradley Senior Administrative Secretary “Parallel Lives: Black and White Women in Amanda Sanders American History” Offi ce Assistant Ronnie Biggs A quilt created by the graduate students of Secretary, History/OHRO HIST 7980/8980, Spring 2005 Greetings from the Chair... e have had an extraordinary year in the History Department. PersonnelW changes, curriculum revisions, and new projects keep us excited and invigorated. Drs. Beverly Bond, Aram Goudsouzian, and Arwin Smallwood exam- ined and extensively revised our African American history curriculum, and the department added a Ph.D. -

The University of Memphis-Emergency Action Plan Fedex Park

The University of Memphis-Emergency Action Plan FedEx Park Emergency Communications: 1.) Cell phone 2.) Landline in the coach’s office or Athletic Training Room Baseball Door Code: 241 Assignment of help: 1. Designate someone to call 911/ 678-HELP [678-4357] 2. Designate someone to await the ambulance at entrance Getwell Rd. of facility (AD or Coach) 3. Designate someone to get available medical equipment (splints, AED, etc). The AED is located in the Baseball Athletic Training Room and will be on-site during game events 4. Designate someone to assist as needed Field entrance location: FedEx 1115 E. Getwell Loop, Memphis, TN 38152 Park Turn off Getwell into the University of Memphis Park Avenue Campus. Follow Park Loop 0.3 miles and turn right. * This gate can be unlocked using the M key The field gate is unlocked and located on the North East corner (3rd base side) with easy access to the field Please contact the athletic trainer in the event an emergency were to take place: Nearest hospital location: 1. Alex Wolfinger, Baseball Graduate Assistant Athletic Trainer [609.571.2999] Methodist University Hospital 1265 Union Ave. Memphis, TN 38104 [901.516.8193] When calling emergency personnel give the following information: Tell campus dispatch that you are an ATC and you are requesting EMS. Provide injured persons gender and age. Provide as much detail as possible regarding the number of victims, condition of each, details of what happened, treatment given, symptoms experienced, etc. Notify coach, event coordinators, or staff athletic trainer that the athlete will require EMS transport. -

"Rebels to the Core": Memphians Under William T. Sherman

"Rebels to the Core": Memphians under William T. Sherman By John Bordelon Tis idle to talk about Union men here. Many want Peace, and fear war & its results but all prefer a Southern Independent Government, and are fighting or working for it. Major General William T. Sherman 1 Memphis, Tennessee, August 11, 1862 Citizens representing various segments of Memphis society, from a southern judge to daring "lady smugglers," engaged in unconventional warfare against the occupying Union presence under Major General William Tecumseh Sherman. White Memphians resisted Federal occupation and aided the Confederacy by smuggling goods, harboring spies, manipulating trade, burning cotton, attacking steamers, and expressing ideological opposition through the judicial system. In occupied Memphis, Sherman never confronted a conventional army. Instead, he faced relentless opposition from civilians sympathetic to the Confederacy. Previous scholarship on Memphis during the Civil War treats examines the city's experience from numerous angles.2 However, the extent of civilian devotion to the Confederacy and willingness to actively pursue their cause deserves further exploration. Focusing on the actions of pro-Confederate Memphians during one officers tenure in the occupied city allows for a more intimate understanding of the character of the city during wartime. Because of a shortage of extant writings of Memphians during the war, the correspondence of W T. Sherman provides valuable insight into the experience of the city in 1862. 1 W T. Sherman to Salmon P. Chase, August 11, 1862, as published in Brooks D. Simpson and Jean V. Berlin, eds., Sherman's Civil Wftr: Selected Correspondence ofWilliam T Sherman, 1860-1865 (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 270. -

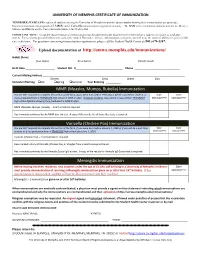

Certificate of Immunization Form

UNIVERSITY OF MEMPHIS CERTIFICATE OF IMMUNIZATION TENNESSEE STATE LAW requires all students entering the University of Memphis to provide documentation showing their immunizations are up-to-date. Documentation must contain proof of 2 MMR and 2 Varicella immunizations or proof of immunity. The MMR is the combination immunization for the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella and the Varicella immunization is for Chicken Pox. IMPORTANT NOTE: Acceptable documentation of immunizations must be submitted to the Student Health Center before a student can register as a full-time student. Forms missing personal information, such as the Student ID number, will take additional processing time and will delay the student’s ability to register for full- time credit hours. For questions concerning immunization requirements, please call the Student Health Center at (901) 678-2287. Upload documentation at http://umwa.memphis.edu/immunizations/ NAME (Print)_________________________________________________________________________________________________________ (Last Name) (First Name) (Middle Initial) Birth Date ____________________ Student ID# U________________________________ Phone _______________________________ Current Mailing Address _________________________________________________________________________________________________ (Street) (City) (State) (Zip) Semester Entering Fall Spring Summer Year Entering __________ MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) Immunization You are NOT required to complete this section of the form, if you were born before 1957, if you will be a part-time student, or Date Date if you graduated from a TENNESSEE high school in 1999 or after. Graduate Students may submit a copy of their TENNESSEE MM/DD/YYYY MM/DD/YYYY high school diploma showing they graduated in 1999 or after. MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) – 2 immunizations required. Has immunity confirmed by the MMR titer lab test. A copy of the results for all three titer tests is required. -

Residency Appeal Form

APPLICATION FOR RESIDENCY CLASSIFICATION In order that we may have full information with which to determine your classification for the purpose of paying fees, it is necessary that you complete and return this form to the Office of Admissions, 101 Wilder Tower, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee 38152-3520. Read all the questions carefully before attempting to answer them. The burden of proof of all conditions pertaining to residence is placed upon the student and/or his parents or guardian, including the responsibility for submission of any necessary documentary substantiation. Guidelines for the classification of students for fee paying purposes are available online at: http://www.memphis.edu/admissions/residency.php. PLEASE NOTE: Residency appeals are reviewed only after an admission decision has been made. UofM STUDENT ID STATUS P(Check One) Single Male Married Male U ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ Single Female Married Female FULL LEGAL NAME P(Please Print) LAST FIRST MIDDLE/MAIDEN SUFFIX PRESENT HOME ADDRESS P(Please Print) APT # / STREET ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP DATE YOU MOVE TO PRESENT ADDRESS – MONTH / DAY / YEAR PERMANENT HOME ADDRESS P(Please Print) APT # / STREET ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP (AREA CODE) PHONE NUMBER TN-COUNTY BIRTHDATE VOTER REGISTRATION / AUTO LICENSE / DRIVER’S LICENSE NUMBERS P (month / day / year) VOTER REGISTRATION NUMBER / STATE AUTOMOBILE LICENSE NUMBER / STATE DRIVERS’S LICENSE NUMBER / STATE HOUSING INFORMATION P Do you own the dwelling in which you live? Yes No Date of purchase: (month / year) -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 52/Monday, March 18, 2019/Notices

9820 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 52 / Monday, March 18, 2019 / Notices Additional Requestors and Disposition additional requestors come forward, Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas; Lineal descendants or representatives transfer of control of the human remains Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma; Lac of any Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian to the Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior organization not identified in this notice organizations stated in this notice may Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin; Lac du that wish to request transfer of control proceed. Flambeau Band of Lake Superior of these human remains and associated DATES: Representatives of any Indian Chippewa Indians of the Lac du funerary objects should submit a written Tribe or Native Hawaiian organization Flambeau Reservation of Wisconsin; Lac request with information in support of not identified in this notice that wish to Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior the request to Mary Beth Miller, Interim request transfer of control of these Chippewa Indians of Michigan; Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, Minnesota Dean of Social Sciences, in care of Jill human remains should submit a written (Six component reservations: Bois Forte Minar, Ph.D., Fresno City College of The request with information in support of Band (Nett Lake), Fond du Lac Band, State Center Community College the request to the Historical Society of Grand Portage Band, Leech Lake Band, District, 1101 E University Avenue, Saginaw County, Inc. at the address in Mille Lacs Band, White Earth Band); Fresno, CA 93741, telephone (559) 442– this notice by April 17, 2019. Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior 8210, email jill.minar@ ADDRESSES: Jeffrey Sommer, Historical Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin; Red fresnocitycollege.edu, by April 17, 2019. -

Sharon K. Mcnary 1026 Pheasant Hollow Drive Cordova, Tennessee 38018 (901) 921-9723

Sharon K. McNary 1026 Pheasant Hollow Drive Cordova, Tennessee 38018 (901) 921-9723 Overview Offering a proven track record in education, educational leadership, and program management built on a personal desire to contribute the overall effectiveness of the Memphis City School System. Have been an active participant and presenter in numerous educational development symposiums, leadership conferences, special educational programs, and teacher workshops. Experience includes extensive knowledge of special education, elementary, middle, and high school operations, a skillful ability to improve parent/teacher interaction, curriculum review and development experience, participation and support of special educational programs. ➢ Established a 35- year record with the Memphis City/Shelby County School System in roles including Principal, Assistant Principal, Lead Teacher, and Teacher. ➢ Experienced in coordinating programs involving parents, teachers, students, and the community at a Blue Ribbon National School of Excellence. ➢ Received outstanding evaluations from my supervisors. ➢ Recognized as a Level 5 School 5 consecutive years Strengths and Abilities ➢ Know how to use personal initiative to provide strong leadership and guidance to associates. Recognized for quality preparation and follow through of tasks. ➢ Able to assess goals and recommend changes in procedures needed to increase effectiveness of educational programs. ➢ Skilled at interacting with students and parents: and between/among principals, teachers, and other individuals that may fall under the jurisdiction of the school district. ➢ Encourage partnerships among the community, school system and private enterprise. ➢ Have extensive record of service to the community with various committees and groups with a common goal of Better Education" for all students. ➢ Experienced in monitoring, coordinating, instructing, and implementing education programs, based on compliance with local, state, and federal guidelines. -

Style Guidelines

STYLE GUIDELINES UPDATED JULY 2019 INTRODUCTION In writing and editing materials for publication, the University of Memphis relies primarily upon The Associated Press Stylebook. The AP stylebook is the preferred editing reference for materials directed at general audiences. Consequently, it is widely used nationwide in the preparation of text for serial publications, newspapers and marketing materials. The UofM Style Guidelines supplements AP by offering guidance on a variety of University-specific exceptions. On some issues, in accordance with an academic culture, it differs from AP. For questions not covered by either AP or the UofM Style Guidelines, please contact your marketing manager. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Bulleted and Numbered Lists Cities/States Commas in a List Dashes and Hypens 2 Dates Phone Numbers Symbols Times Titles Type Formatting 3 University Colleges and Departments UofM Locations Websites 4 Samples BULLETED AND NUMBERED LISTS In a vertical list, it is best if the listing is first introduced by a Examples complete grammatical sentence, followed by a colon. After each Other online innovations have also bullet or number, each entry should start with a capital letter. The been developed: entries should carry no punctuation at the end, unless they are • Financial aid application complete sentences. • Web-based class schedule Use bullets when possible to reduce the amount of text. Using • Financial aid awards fewer words is ideal and improves your chances of the reader reviewing your message. CITIES/STATES City should always be capitalized when writing City of Memphis, Examples but city is lowercased when it stands alone. The University of Memphis is located in the City of Memphis. -

Kws Career Expo 2021 Employ

Career Expo 2021 Em ployers Joining on Tuesday | February 2, 2021 1 - 2 :30 pm Elvis Presley Enterprises Website: www.graceland.com Offering: • Part-Time • Full-Time Contact: Teresa Chumney Recruiter 3374 Elvis Presley Blvd. Memphis, TN 38116 901-332-3322 [email protected] American Job Center Website: tnvirtualajc.com Offering: • Job Shadowing • Part-Time • Full-Time Contact: Judy Moorman Career Specialist 1124 Whitehall Street, Suite 100 Jackson, TN 38301 731-668 -2040 [email protected] Doubletree by Hilton, Downtown Website: DoubleTree by Hilton, Downtown Offering: • Part-Time • Full-Time Contact: Patricia Thompson Director, Human Resources 185 Union Avenue Memphis, TN 38103 901-528 -1800 [email protected] McNeil Hospitality Company Hampton Inn Suites Website: www.memphisgermantown.hamptonbyhilton.com Offering: • Part-Time • Full-Time Contact: Tonya Maness General Manager 1680 South Germantown Germantown, TN 38120 901-309 -0555 [email protected] Memphis Fellows Website: www.memphisfellows.com Offering: • Paid Internships • Part-Time Contact: Deb Coleman Memphis Fellows Director 4055 Poplar Avenue Memphis, TN 38111 901-289 -3379 [email protected] Valor Hospitality Partners Website: www.valorhospitality.com Offering: • Paid Internships • Part-Time • Full-Time Contact: Jennifer Murray Regional Human Resources Director 2100 Powers Ferry Road, Suite 370 Atlanta, GA 30339 404 -846 -0700 [email protected] South of Beale Website: www.southofbeale.com Offering: • Paid Internships • Part-Time • Full-Time • Job -

Departmental Communication

We cordially invite you to participate in this community environmental project: Reducing Exposure to Airborne Chemical Toxics (REACT) via Community-Scale Air Monitoring in Memphis What is the REACT study? The REACT study is funded by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It aims to measure the pollution levels of toxic air pollutants (also called “air toxics”) in the Memphis area. The results are expected to tell whether the air toxics in your neighborhood can cause any adverse health effects. The study will rely on a major collaboration of the Shelby County Health Department, the University of Memphis, and the Middle Tennessee State University to perform air toxics sampling and analysis. Why are you being invited to take part in this research? You are being invited to take part in this study because the location of your home may be representative of your neighborhood. What are the eligibility requirements? You are eligible to participate if you have a secured (e.g., fenced) backyard and allow our field staff to deploy the sampler(s) there. Where is the study going to take place and how long will it last? We will have four visits to your backyard, one time each season over a one- year period. At each visit, our field staff will deploy one or two canisters in your backyard, and leave them there for 1 day. The deployment of sampling devices will take about 15 minutes, and the retrieval will take about 10 minutes. The field staff will perform all the operations. The canister does not require any power or care, nor does it have any noise. -

University of Memphis Campus Map BUILDING ABBRLOCATIONFLOOR PLANS ADDRESS CITY, STATE ZIP Administration 3720 Alumni Avenue Memphis, TN 38152-3370 AD F-9 Building

411612014 Universi1;)1 of Merqihis Campus Map THE UNIVERSITY OF MEMPHIS.. M A I N C A M P U S h11p:lhnap.merqihis.edu/ 114 4/16/2014 University of Memphis Campus Map BUILDING ABBRLOCATIONFLOOR PLANS ADDRESS CITY, STATE ZIP Administration 3720 Alumni Avenue Memphis, TN 38152-3370 AD F-9 Building Alumni Center AC I-15 635 Normal Street Memphis, TN 38152-3760 Annex IV N/A N/A N/A 505 Zach H Curlin Street Memphis, TN 38152 Art and 3715 Central Avenue Memphis, TN 38152-3140 Communication ACB F-5 Building Art Building AB E-8 3700 DeSoto Avenue Memphis, TN 38152 Athletic Office 570 Normal Street AOB K-13 Memphis, TN 38152-3730 Building Ball Hall, E.C. BH I-12 3798 Walker Avenue Memphis, TN 38152-3570 Baptist Student Union 1 C-10 N/A 469 Patterson Street Memphis, TN 38111 Barth House 2 C-8 N/A 409 Patterson Street Memphis, TN 38111 Episcopal Center Billy Mac Jones BMJ J-15 633 Normal Street Memphis, TN 38152-3750 Building Bookstore / V. Lane 506 University Memphis, TN 38152 Rawlins Service Court BS H-11 Facility Brister Hall, John 3669 Alumni Avenue Memphis, TN 38152 JWB D-11 Willard Browning Hall BR I-8 3820 DeSoto Avenue Memphis, TN 38152-3340 Campus School CS J-12 535 Zach H Curlin Street Memphis, TN 38152-3580 Carpenter Student 3875 Tiger Paw South Memphis, TN 38152-3920 CSH J-3 N/A Housng Cmplx-Comty Bldg, Thomas G. Catholic Student 3625 Mynders Avenue Memphis, TN 38111 3 B-11 N/A Center CERI, 3876 Central EQ1 K-4 3876 Central Avenue Memphis, TN 38152-3050 CERI, 3890 Central EQ2 K-4 3890 Central Avenue Memphis, TN 38152-3050 CERI, 3892 Central EQ3 K-4 3892 Central Avenue Memphis, TN 38152-3070 CERI, 3904 Central EQ4 K-4 3904 Central Avenue Memphis, TN 38152-3080 CERI, 3918 Central EQ5 K-4 3918 Central Avenue Memphis, TN 38152-3090 Christian Student 3611 Midland Avenue Memphis, TN 38111 Center (Church of 4 B-10 N/A Christ) Clement Hall CL E-11 3704 Walker Avenue Memphis, TN 38152-3530 Clock Tower, V.