Dissertation Shams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of National Bank of Pakistan (NBP), District Attock, Pakistan

World Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 1. No. 4. September 2011. Pp.195-206 A Comparison of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Compensation Instruments: The Case of National Bank of Pakistan (NBP), District Attock, Pakistan Ahmad Jamal Tahir1, Rosman Bin Md. Yusoff2, Anwar Khan3, Kamran Azam4, Muhammad Sohaib Ahmed5 and Muhammad Zohair Sahoo6 The paper aims to compare the compensation instruments which are used as the factors of motivation in the banking sector of Pakistan. With a case study research design, structured interviews were conducted from the fifty ( 5 0 ) employees of NBP branches in district Attock. The responses of interview were scaled and scored according to standardized Likert technique, in such a way that scores for each response were added and then multiplied with total responses. After obtaining scores of the nine compensation factors, Pearson Product correlation was calculated to check the relationship between the compensation factors. The results show that the employees of National Bank of Pakistan were motivated both by the intrinsic as well extrinsic factors of compensation, in such way that extrinsic factors were more causing motivation. The paper has concluded that Compensation Management has a profound direct positive relationship with employee motivation level and intrinsic factors played important role in the motivation process. The paper recommends that public sector banks shall apply progressive human resource strategy and provide healthy compensation plans regarding benefits and intrinsic factors. Field of Research: Human Resource Management 1. Introduction The financial assets of a company have always occupied central importance whenever it has come to management decisions. However world’s recent plunge into financial crisis has raised this importance to critical level. -

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Reigd

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Islamic Republic of Pakistan Reigd NEPRA Tower, Attaturk Avenue (East), G-5/1, Islamabad. Ph: +92-51-9206500, Fax: +92-51-2600026 Registrar Web: www.nepra.org.pk, E-mail: [email protected] No. NIEPRA/TRE-336/1ESCO-2015/15633-15635 September 18, 2017 Subject: Re-determination of the Authority in the matter of Request for Reconsideration pertaining to the Tariff Determination dated February 29, 2016 and Review Decision dated May 18, 2016 with respect to Islamabad Electric Supply Company Ltd. (IESCO) for the FY 2015-16 to 2019-2(1 under Section 31(4) of E RPA Act 1997 I Case # NEPRA/ fRF-336/1ESC0-2015 Dear Sir. Enclosed please find herewith the subject Re-determination of the Authority along with Annex-I. 11. III. IV. V. VI and VII (67 Pages) in Case No NEPRA/TRF-336/IESCO-20 15. 7, the Re-Determination is being intimated to the Federal Government pursuant 31(4) of the Regulation of Generation. Transmission and Distribution of Electric Power Act (XL of 1997). 3. The Order Part along with Annex-I. II. III, IV, V. VI and VII of Re-determination of the Authority arc to be notified in the official Gazette. ) Enclosure: ;As above r\,'V.K7 ai 11 ( Svcd Sated' I Secretary Ministry of Energy 'A' Block. Pak Secretariat Islamabad CC: 1. Secretary. Cabinet Division. Cabinet Secretariat. Islamabad 2. Secretary. Ministry of Finance. `Of Block, Pak Secretariat, Islamabad. Re-deterinination of the Authority in the matter of request for reconsidena ion filed by GoP with respect to the consumer-end tariff of Islamabad Electric Supply Company Limited (IESCO) for FY 2015-16 to FY 2019-20 RE-DETERMINATION OF THE AUTHORITY IN THE MATTER OF REQUEST FOR RECONSIDERATION PERTAINING TO THE TARIFF DETERMINATION DATED FEBRUARY 29, 2016 AND REVIEW DECISION DATED MAY 18, 2016 WITH RESPECT TO IESCO FOR THE FY 2015-16 TO FY 2019-20 UNDER SECTION 31(4) OF NEPRA ACT 1997 1. -

Int. J. Biosci. 2020

Int. J. Biosci. 2020 International Journal of Biosciences | IJB | ISSN: 2220-6655 (Print), 2222-5234 (Online) http://www.innspub.net Vol. 16, No. 3, p. 221-230, 2020 RESEARCH PAPER OPEN ACCESS Faunistic study of Non-Apis bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) from Potohar Plateau of Pakistan Sumera Aslam1*, Muhammad Ather Rafi1, Syed Ahmed Zia1, Anjum Munir1, Ahmad- Ur-RahmanSaljoki2 1Department of Plant and Environmental Protection, PARC Institute of Advance Studies in Agriculture, National Agricultural Research Centre (NARC) Islamabad, Pakistan 2Department of Plant Protection, University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Pakistan Key words: Non-apis bees, Megachilidae, Halictidae, Andrenidae, Colletidae. http://dx.doi.org/10.12692/ijb/16.3.221-230 Article published on March 18, 2020 Abstract This study was conducted to explore the fauna of non-apis bees of Potohar region of Pakistan. To carry out this study (36) surveys were conducted during three consecutive years i.e. from January, 2011 to December 2013. This study of non-apis bees revealed (27) species in 13 genera and five families. The taxonomic accounts of Halictidae, Colletidae, Megachilidae, and Andrenidae were given. The family Halictidae from its subfamily Nomiinae comprises two (2) species and three species(3) from subfamily Halictinae, the Colletidae from its subfamily Colletinae one (1) species and subfamily Hylaeinae one (1) species, the family Megachilidae from its subfamily Megachilinae five (5) species and the family Andrenidae from its subfamily Andreninae one (1) species were recorded. The following species are new records to Pakistan, Megachile bicollar,Megachile cephalotes, Megachile conjuncta, Megachile disjuncta, Coelioxys decipiens, Halictus splendidulus, Halictus albescens, Lassioglossum albescens, Colletes inaequalis, Hylaeus scutellaris, Andrena flavipes and Nomia westwoodi. -

NCOC Hints at Another Lockdown

Soon From LAHORE & KARACHI A sister publication of CENTRELINE & DNA News Agency www.islamabadpost.com.pk ISLAMABAD EDITION IslamabadThursday, October 22, 2020 Pakistan’s First AndP Only DiplomaticO Daily STPrice Rs. 20 Only a sovereign Bringing down Pakistan keen to Afghan govt can avert prices govt priority, expand bilateral civil war: Hekmatyar says Shibli Faraz relations with Iraq Briefs NCOC hints Country heading in right at another direction DNA lockdown ISLAMABAD: In a tweet on Wednes- Wearing of mask and social distancing day, he said must be ensured. Administrative actions the current account was be initiated against violators,” the in surplus of seventy NCOC told the chief secretaries three million dollars during September bringing sur- noted the rising death rate attributable aHNoor NSar plus for the first quarter M a / dNa to COVID-19. The chief secretaries, who to 792 million dollars com- attended the meeting, were directed to ISLAMABAD: The National Command and “strictly implement” SOPs. They were also pared to deficit of 1,492 Operations Centre (NCOC), which oversees ISLAMABAD: EU ambassadors had a very interesting and constructive discussion with the million dollars during the directed to take “strict punitive actions” if Pakistan’s response to the coronavirus pan- a violation of the SOPs is observed. Chairman of Islamic Ideology Dr. Qibla Ayaz at CII. Dialogue and further understanding is same time last year. demic, on Wednesday warned that the coun- vital for achieving the mutual objective of Inter-faith dialogue and peace in the world. – DNA The Prime Minister said It also directed officials to put a “special fo- try is fast approaching a point where there cus” on the perceived high-risk sectors of exports grew twenty nine will be “no choice” left but to impose anoth- percent and remittances transport, markets, marriage halls, restau- er sweeping lockdown. -

Tender Notice

TENDER NOTICE Sealed tenders of following works on percentage rate MRS 2nd Biannual (1st July 2017 to 31st December , 2017) and item rates for non scheduled items from the approved contractors/ firms which are enlisted/ renewed with LG & CD Department Government of the Punjab and also deposited fee with the Department for the financial year 2017-18. EARNEST T.S NO. SR. ESTIMATED TENDER TIME NAME OF WORK MONEY & NO. COST RS: COST RS: LIMIT RS: DATE LOCAL GOVERNMENT DEVELOPMENT PACKAGE 2017-18 DISTRICT ATTOCK TEHSIL HAZRO. Construction of Streers/Drains i. From Masjid to Haveli Sadaqat Khan In village Bara ii. In front of H/O Bashir Hussain Moh.Faqeeria Abad No.440/TS/XEN in village Bara. LG&CD/Civil AS PER 1. iii. From Dera Khan Kaka to 2.500 50000/- 10000/- Div.RWP/2017- WORK Dera Wakalat Khan in 18 Dated ORDER village Chothai 08.01.2018 iv From H/O Zubiar Shah to Dera Noreen Shah in village Changa. UC Haroon Tehsil Hazro District Attock. Construction of Streets / Drains i. From H/o Waqas to H/o Tariq Khan in village Formali. ii. From H/o Saif ur Rehman to No.441/TS/XEN H/o Noor ul Haq in village LG&CD/Civil AS PER 2. 2.500 50000/- 10000/- Div.RWP/2017- WORK Sirka. 18 Dated ORDER iii. From H/o Ali Rehman to 08.01.2018 H/o Doran Khan in village Sirka UC Formali Tehsil Hazro District Attock. Construction of Streets/Drains i. From main Road Tajabaja to Masjid Zakria in village Tajabaja. -

Current Hrm Practices: a Comparative Study to Identify the Impact of Hr Performance in Pakistan

CURRENT HRM PRACTICES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY TO IDENTIFY THE IMPACT OF HR PERFORMANCE IN PAKISTAN. PJAEE, 18 (08) (2021) CURRENT HRM PRACTICES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY TO IDENTIFY THE IMPACT OF HR PERFORMANCE IN PAKISTAN. Anita Larik1, Dr. Shoeb Ahmed Bukhari2 1 Phd Scholar, Hamdard University Karachi 2 Assistant Professor Hamdard University Karachi Email: [email protected], [email protected] Anita Larik, Dr. Shoeb Ahmed Bukhari. Current Hrm Practices: A Comparative Study to Identify the Impact of Hr Performance in Pakistan. -- Palarch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 18(08), 546-566. ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: Hrm Practices, Comparative Study, Hr Performance, Hr Policies, Public Banks, Private Banks, Banking Sectors. ABSTRACT: The audit of the paper has been directed and following are the experimental discoveries that 12-14 examination papers have been surveyed and each exploration has its own discoveries. Motivation behind this investigation was to examine the effect of best Human Resource Management (HRM) rehearses on Human Resource Management (HRM) results inside the associations of Asian nation (PK). This is frequently a relative report between people in general and private association of Asian country. data of the examination was gathered through organized structure including 54 things chiefly connected with Best HRM Practices for example accomplishment and decision, instructing and Development, Performance Appraisal, Promotion, Compensation and Social benefits, and time unit Outcomes for example specialist Satisfaction (ES), laborer Commitment (EC) and specialist Retention (ER). This is regularly quantitative examination inside which Multiple Regressions, Cronbach alpha, Pearson’s correlation coefficient test measured the statistical relationship and was utilized for fluctuated investigations of this investigation. -

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Islamic Republic of Pakistan

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Islamic Republic of Pakistan NEPRA Tower, Attaturk Avenue (East), G-5/1, Islamabad Ph: +92-514206500, Fax: +92-51-2600026 Web: www.nepra.org.pk, regletrar©nepra.org.pk No. NEPRAJTRF-336/IESCO-2015/2689-2691 February 29, 2016 Subject: Determination of the Authority in the matter of Petition filed by Islamabad Electric Supply Company Ltd. (IESCO) for the Determination of its Consumer end Tariff Pertaining to Financial Years 2015-2016 to 2019-20 [Case # NEPRA/TRF-336/IESCO-20151 Dear Sir, Please find enclosed herewith the subject Determination of the Authority along with Annexure-I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII & IX (140 pages) in Case No. NEPRA/TRF-336/IESCO- 2015. 2. The Determination is being intimated to the Federal Government for the purpose of notification of the approved tariff in the official gazette pursuant to Section 31(4) of the Regulation of Generation, Transmission and Distribution of Electric Power Act (XL of 1997) and Rule 16(11) of the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (Tariff Standards and Procedure) Rules, 1998. 3. The Order part along with Annexure-I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII & IX of the Determination needs to be notified in the official Gazette. Enclosure: As above a"). • Vzb ( Syed Safeer Hussain ) Secretary Ministry of Water & Power `A' Block, Pak Secretariat Islamabad CC: 1. Secretary, Cabinet Division, Cabinet Secretariat, Islamabad. 2. Secretary, Ministry of Finance, 'Q' Block, Pak Secretariat, Islamabad. Decision of the Authority in the matter ofIslamabad Electric Supply Company Limited No. NEPRAITRF-33641ISCO-2015 National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) PETITION NO: NEPRA/TRF-336/IESCO-2015 TARIFF DETERMINATION FOR ISLAMABAD ELECTRIC SUPPLY COMPANY (IESCO) DETERMINED UNDER NEPRA TARIFF (STANDARDS AND PROCEDURE) RULES -1998 Islamabad cZ g it February, 2016 IL% Decision of the Authority in the matter of hiantabad Electric Supply Company Limited No. -

BAFL ATM Locations

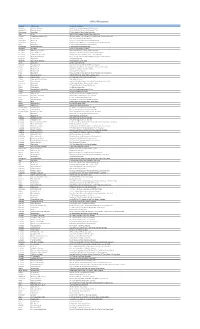

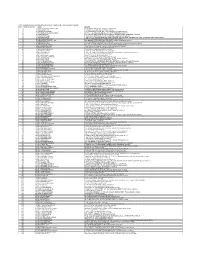

BAFL ATM Locations City Name ATM Location Complete Branch Address Abbottabad Abbotabad City Branch Shop No.C-15,Cantt Bazar,Opposite GPO,Abbottabad Ahmedpur East Ahmed pur Branch Plot No.188, Block-XI, Kutchery Road, Ahmedpur East. Aliabad, hunza Hunza Nagar SM Karim Market, Ali Abad, District Hunza Nagar Alipur Ali Pur Plot# W/R 1018, Opposite ACHouse, Multan Road, AliPur, Allahabad Theeng More Allahabad Branch Main Kasur Depalpur Road, Theeng More, Allahabad, Tehsil Chunian, District Kasur Arifwala Arifwala Branch 47/D, Zain Palace, Qaboola Road, Arifwala Azad Kashmir Bhimber AK Ashraf Center,Ground Floor, Mirpur Chowk-Bhimber AJK Azad Kashmir Dadyal AK Shop No. 1, Iftikhar Memorial Plaza, Ground Floor, Zaman Chowk,Dadyal AJK Badin Badin Branch Survey No 30 Ward 4 Deh Sonhar, Main Road Badin. Bahawalnagar Bahawalnagar Branch Shop # 06 Ghalla Mandi, Bahawalnagar, Bahawalpur Fort Abbas Plot # 44-C Grain Market, Fort Abbas. Bahawalpur Mandi Sadiq Gunj Branch Plot#25, Mandi Sadiq Gunj Branch, District Bahawalpur Bahawalpur Liaquat Pur Branch Plot#135, Near Ghanta Ghar Chowk, Rest House Road, Liaquat Pur Bahawalpur Satellite Town, Bahawalpur Plot # 19-D, near One Unit Chowk, Satellite Town, Bahawalpur Balochistan Muslim Bagh Balochistan Khasra No. 1750, Station Road Muslim Bagh District Qilla Saifullah, Balochistan Balochistan Zhob Branch H/129 Tehsil Road Zhob. Balochistan Dukki Branch, Balochistan Majid Road Dukki, District Loralai Bannu Bannu Branch Gowshala Road Fatima Khel Battagram Battagram Branch Opposite D.H.Q. Hospital, Shahrah-e-Resham, Battagram Besham Besham Branch, Aftab Market Main Shahrah-e-Karakorum Besham Bazar,District Shangla. Bhakkar Bhakkar Branch Plot# 458, Dagar Gharbi, Jhang Road, Bhakkar Bhalwal Bhalwal Branch Liaqat Shaheed Road, Bhalwal. -

Appendix VII Bank Wise Atms¶ Locations As on 31St December 2011

Appendix VII %DQN:LVH$70V¶/RFDWLRQV As on 31st December 2011 Depalpur Albaraka Bank Abdul Hakim (Pakistan) Ltd. (35) Adda Nandi Pur Dera Ghazi Khan (2) Ahmedpur East -Azmat Road Daska Akalgarh A.K. -Model Town Faisalabad Akwal Gujranwala Alipur Chatha Dhangri Bala A.K. Hyderabad Arifwala Dhudial, District Chakwal Attock Isalmabad (3) Bagh Di Khan (2) -F-7 Jinnah Super Markaz Bahawal Nagar -Circular Road -Jinnah Avenue Blue Area -Khalid Market, Laghari Gate -Shifa International Hospital, Bahawalpur (4) -Dubai.Chowk Bwp Dina Karachi (12) -Farid Gate Bwp Dinga -Banglore Town, Main Shahrah e Faisal, -Grain Market, Dunyapur -Block-7, F. B. Area, -S.Town Bwp Ellahabad -Boat Basin, Block 5, Clifton -Fiver Star Chowrangi, Balakot Faisalabad (25) -Korangi Industrial Area, Bannu -15 Club Road, -Main Branch, Al Farid Center, PIDC Bara Kahu -Canal Road, Faialabad -Main Khayabane Shahbaz Phase VI Bhakkar -Chibban, -Nishat Lane No.4, Phase-VI, DHA, -Factory Area. -Phase-II, D.H.A, Bhalwal (2) -Ghulam Muhammad Abad. -Shaheed-e-Millat Road, -Liaqat Shaheed Road -Gole Cloth Market, -Site Area, -Noor Hayat Colony -Gole Karyana. -University Road, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, -Gulberg Colony. Bhirya -Gulistan Colony (Akbar Chowk). Lahore (7) -Jaranwala Road. -Allama Iqbal Town, Gulshan Block Burewala (2) -Jinnah Colony -Block R-1, Johar Town, - Grain Market -Kotwali Road. -Block-Y, Phase III, DHA, -Housing Scheme -Madina Town (Bismillah Chowk). -Cavalry Ground Lahore -Main Bazar, Chak Jhumra, -DHA S Block Chak No.61 Rb (2) Khurrianwala -M.M. Alam Road Gulberg III, -Sheikhupura Road, Jaranwala (2) -Manawala. -Shadman Colony -Model Branch, Kotwali Road. Chakswari A.K. -

Clearing Operations

Detail of Branches Dealing with Intercity Instruments I/W CLG Province City Branch Code Branch Name Address CPU Clearing Trade Centre, I.I. 1 Sindh Karachi 110 Chundrigarh Road Faysal House,St- 02,Main Shahra-e-Faisal, Karachi 2 Sindh Hyderabad 138 Main Hyderabad Plot No. 339, Main Bohra Bazar Saddar, Hyderabad 3 Sindh Nawabshah 272 Nawabshah Br CS No. 555,Ward B, Main Mohni Bazar, Nawabshah City Survey No. D1596 / 1-D, Race Cource Road , Sukha 4 Sindh Sukkar 230 Sukkar Talab, Sukkur City Survey No. 715, 716 And 718, Ward A, Umerkot Road, 5 Sindh Mirpurkhas 258 Mirpurkhas Taluka And District, Mirpurkhas City Survey No. 2016/ 4-A Ward C, Faysal Bank Chowk, 6 Sindh Larkana 287 Larkana Larkana City Ground Floor, City Survey No. 890, Ward-B, Situated At 7 Sindh Ghotki 292 Ghotki Devri Sahab Road, Ghotki 8 Baluchistan Quetta 115 ADALAT ROAD, Quetta Shahrah-e-Adalat Road, Quetta 9 Punjab Lahore 112 CPU Lower Mall Lahore 43, Shahrah-e-Quaid-e-Azam, Lahore 10 Punjab Sialkot 122 Main Branch Sialkot Plot No.B1-16S-98B, 17-Paras Road, Opp Cc & I, Sialkot 11 Punjab Gujrat 146 Main Branch Gujrat Nobel Furniture Plaza, G.T Road, Gujrat 12 Punjab Gujranwala 128 Main Branch Gujranwala Zia Plaza, G.T. Road, Gujranwala CPU Clearing Main Civil Lines 13 Punjab Faisalabad 111 Faisalabad Bilal Road, Civil Lines Faisalabad 14 Punjab Jhang 163 Jhang Branch P-10/1/A, Katcheryi Road,Near Session Chowk, Saddar Jhang 15 Punjab Multan 133 Multan Main 129/1, Old Bahawalpur Road, Multan. 16 Punjab D.G Khan 448 D.G Khan Block 18, Hospital Chowk, Pakistan Plaza, Dera Ghazi Khan Khewat No. -

List of Members (Physical Shareholder & Cdc

LIST OF MEMBERS (PHYSICAL SHAREHOLDER & CDC ACCOUNT HOLDER) OF M/S. HINO PAK MOTORS LIMITED S NO. FOLIO/CDC A/C NO NAME ADDRESS 1 3 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 2-3-13, KONAN, MINATO-KU, TOKYO, 108-8208, JAPAN. 2 4 HINO MOTORS LTD. 1-1, HINODAI 3-CHOME HINOSHI, TOKYO, JAPAN., 3 12 MIR MAQSOOD AHMED C/O HINOPAK MOTORS LTD., D-2, S.I.T.E., MANGHOPIR ROAD, KARACHI., 4 13 MR. MANZOOR HUSSAIN QURESHI FLAT NO. 6, AL-FAZAL SQUARE, BLOCK-H, NORTH NAZIMABAD, KARACHI., 5 18 MISS NUSRAT ZIA FLAT NO.19-O, IQBAL PLAZA, BLOCK-O, NAGAN CHOWRANGI, NORTH NAZIMABAD, KARACHI., 6 19 MISS FARHAT SABA H.NO. E-13/40, NEAR RAILWAY LINE, GHARIBABAD, LIAQUATABAD, KARACHI., 7 21 MISS AMUL-HAMID H.NO. R- 60- 1/A, GULSHAN-E-ZAHOOR, NEAR HASHMANI HOSPITAL NEAR MASJID-E-EHTISHAMIA, JACOB LINE, LINES AREA, KARACHI. 8 24 MISS TABASSUM NISHAT R.177-1,SHARIFABAD FEDERAL B.AREA, KARACHI. TEL: 6335769, 9 28 MISS SHAKILA ANWAR FATIMA 52-D, Q-BLOCK, PAHAR GANJ, NEAR LAL KOTTHI, NORTH NAZIMABAD, KARACHI., 10 31 MISS SAMINA NAZ 171/2, AURANGABAD, NAZIMABAD, KARACHI-18. 11 32 MISS FARHAT ABIDI C/O. SYED MUJAHID HUSSAIN P-394, PEOPLES COLONY BLOCK-N, NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI, 12 38 SYED MOHAMMAD HAMID FLAT NO. A-3 FARAZ AVENUE, BLOCK-20 GULISTAN-E-JOHAR KARACHI, 13 40 MR. KHURSHID MAJEED 128-B, ASKERY APARTMENT, ASKARY-5, WALTON AIRPORT, LAHORE. 14 44 MR. SALEEM JAWEED A-284, BLOCK-15, GULISTAN-E-JAUHAR, KARACHI., 15 51 MR. FARRUKH GHAFFAR A-485, BLOCK-D NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI. -

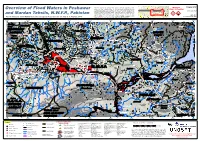

Overview of Flood Waters in Peshawar and Mardan Tehsils, N.W.F.P., Pakistan

!I !")"i !I !I !"i ¥¦¬ !"i i !"i !" !I i Monsoon 2 August 2010 " This map presents the standing flood waters is uncertain (approximately 250- !" Overview of Flood Waters in Peshawar waters over the affected Tehsils of 500m) because of the relatively low spatial Map Exent Rains & Flooding Peshawar and Mardan, N.W.F.P, Pakistan resolution of the satellite sensors used for " following recent heavy monsoon rains. This this analysis, and that detected water Version 1.0 analysis is based on post-disaster satellite bodies likely reflect an underestimation of • and Mardan Tehsils, N.W.F.P., Pakistan imagery collected by MODIS sensors on 31 all flood-affected areas within the map Peshawar ••• i July & 1 August 2010, and pre-crisis by extent.This analysis has not yet been !" !, Glide No: MODIS sensors on 25-26 July 2010. validated in the field. Please send ground Islamabad !! !" Flood Analysis with MODIS Satellite Imagery Recorded on 31 July & 1 August 2010 Please note that the exact limit of the flood feedback to UNITAR / UNOSAT. Rawalpindi FL-2010-000141-PAK " 165000 180000 195000 210000 225000 240000 255000 270000 285000 300000 " Jalala X W i Kaghan Pir Sado 71°30'0"E 71°45'0"E!" " i 72°0'0"E 72°15'0"E 72°30'0"E 72°45'0"E !" !"i !"i Gandaf " " i Munda " !" " i " " !" Sherpao Takhat Yakaghund X W X W Bahai i Swat River 34°15'0"N !" X W " X W " Turangzai 0 Baghicha 0 Michni !"i " 34°15'0"N 379000 i Utmanzai " 379000 " )" MARDAN !" X W i " X W X W Rajar !" " Warsak Yar X W Dam Sheikh Toru Hussain Maltoon Naguman " " Dagi Charsadda Town X W Gunbad