"The Aegean Ogygos of Boeotia and the Biblical Og of Bashan: Reflections of the Same Myth."

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manasseh: Reflections on Tribe, Territory and Text

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Vanderbilt Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive MANASSEH: REFLECTIONS ON TRIBE, TERRITORY AND TEXT By Ellen Renee Lerner Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion August, 2014 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Douglas A. Knight Professor Jack M. Sasson Professor Annalisa Azzoni Professor Herbert Marbury Professor Tom D. Dillehay Copyright © 2014 by Ellen Renee Lerner All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people I would like to thank for their role in helping me complete this project. First and foremost I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee: Professor Douglas A. Knight, Professor Jack M. Sasson, Professor Annalisa Azzoni, Professor Herbert Marbury, and Professor Tom Dillehay. It has been a true privilege to work with them and I hope to one day emulate their erudition and the kind, generous manner in which they support their students. I would especially like to thank Douglas Knight for his mentorship, encouragement and humor throughout this dissertation and my time at Vanderbilt, and Annalisa Azzoni for her incredible, fabulous kindness and for being a sounding board for so many things. I have been lucky to have had a number of smart, thoughtful colleagues in Vanderbilt’s greater Graduate Dept. of Religion but I must give an extra special thanks to Linzie Treadway and Daniel Fisher -- two people whose friendship and wit means more to me than they know. -

Chukat Artscroll P.838 | Haftarah P.1187 Hertz P.652 | Haftarah P.664 Soncino P.898 | Haftarah P.911

13 July 2019 10 Tammuz 5779 Shabbat ends London 10.16pm Jerusalem 8.28pm Volume 31 No. 45 Chukat Artscroll p.838 | Haftarah p.1187 Hertz p.652 | Haftarah p.664 Soncino p.898 | Haftarah p.911 In loving memory of Yehuda ben Yaakov HaCohen “Speak to the Children of Israel, and they shall take to you a completely red cow, which is without blemish, and upon which a yoke has not come” (Bemidbar 19:2). 1 Sidrah Summary: Chukat 1st Aliya (Kohen) – Bemidbar 19:1-17 Kadesh through his land. Despite Moshe’s God tells Moshe and Aharon to teach the nation assurances that they will not take any of his the laws of the Red Heifer ( ). The resources, Edom refuses and comes out to unblemished animal, which hPaasr anhe vAedr uhmada h a yoke threaten the Israelites militarily. The Israelites upon it, is to be given to Elazar, Aharon’s son, who turn away. must slaughter it outside the camp. It is then to be 5th Aliya (Chamishi) – 20:22-21:9 burned by a different Kohen, who must also throw The nation travels from Kadesh to Mount Hor. some cedar wood, hyssop and crimson thread Upon God’s command, Moshe, Aharon and Elazar into the fire. Both he and Elazar will become ritually ascend Mount Hor. Elazar dons Aharon’s special impure ( ) through this preparatory process. (High Priest) garments, after which In contratasmt, ethe ashes of the Heifer, when mixed AKhohareonn G daiedso.l The nation mourns Aharon’s death with water, are used to purify someone who has for 30 days (see p.3 article). -

Good News & Information Sites

Written Testimony of Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) National President Morton A. Klein1 Hearing on: A NEW HORIZON IN U.S.-ISRAEL RELATIONS: FROM AN AMERICAN EMBASSY IN JERUSALEM TO POTENTIAL RECOGNITION OF ISRAELI SOVEREIGNTY OVER THE GOLAN HEIGHTS Before the House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Subcommittee on National Security Tuesday July 17, 2018, 10:00 a.m. Rayburn House Office Building, Room 2154 Chairman Ron DeSantis (R-FL) Ranking Member Stephen Lynch (D-MA) Introduction & Summary Chairman DeSantis, Vice Chairman Russell, Ranking Member Lynch, and Members of the Committee: Thank you for holding this hearing to discuss the potential for American recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights, in furtherance of U.S. national security interests. Israeli sovereignty over the western two-thirds of the Golan Heights is a key bulwark against radical regimes and affiliates that threaten the security and stability of the United States, Israel, the entire Middle East region, and beyond. The Golan Heights consists of strategically-located high ground, that provides Israel with an irreplaceable ability to monitor and take counter-measures against growing threats at and near the Syrian-Israel border. These growing threats include the extremely dangerous hegemonic expansion of the Iranian-Syrian-North Korean axis; and the presence in Syria, close to the Israeli border, of: Iranian Revolutionary Guard and Quds forces; thousands of Iranian-armed Hezbollah fighters; Palestinian Islamic Jihad (another Iranian proxy); Syrian forces; and radical Sunni Islamist groups including the al Nusra Levantine Conquest Front (an incarnation of al Qaeda) and ISIS. The Iranian regime is attempting to build an 800-mile land bridge to the Mediterranean, running through Iraq and Syria. -

AMOS 44 Prophet of Social Justice

AMOS 44 Prophet of Social Justice Introduction. With Amos, we are introduced to the proclamation of Amos’ judgment, but rather in the first of the “writings prophets.” They did not only social evils that demand such judgment. preach but also wrote down their sermons. Preaching prophets like Elijah and Elisha did not write down Style. Amos’ preaching style is blunt, confrontational their sermons. In some books of the Bible, Amos and and insulting. He calls the rich ladies at the local his contemporaries (Hosea, Isaiah, etc.), are country club in Samaria “cows of Basham” (4:1). sometimes called the “Latter Prophets” to distinguish With an agricultural background, he uses symbols he them from the “Former Prophets” (Joshua, Samuel, has experienced on the land: laden wagons, roaring Nathan, etc.). lions, flocks plundered by wild beasts. Historical Context. One of the problems we DIVISION OF CHAPTERS encounter when dealing with the so-called “Latter Prophets” is the lack of historical context for their PART ONE is a collection of oracles against ministry. Since little or nothing is written in the surrounding pagan nations. These oracles imply that historical books about any of the prophets, with the God’s moral law applies not only to his chosen ones exception of Isaiah, scholars have depended on the but to all nations. In this series of condemnations, text of each prophetic book to ascertain the historical Judah and Israel are not excluded (chs 1-2). background of each of the prophets. Some of the books provide very little historical information while PART TWO is a collection of words and woes against others give no clues at all. -

Deuteronomy 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Deuteronomy 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible was its first two words, 'elleh haddebarim, which translate into English as "these are the words" (1:1). Ancient Near Eastern suzerainty treaties began the same way.1 So the Jewish title gives a strong clue to the literary character of Deuteronomy. The English title comes from a Latinized form of the Septuagint (Greek) translation title. "Deuteronomy" means "second law" in Greek. We might suppose that this title arose from the idea that Deuteronomy records the law as Moses repeated it to the new generation of Israelites who were preparing to enter the land, but this is not the case. It came from a mistranslation of a phrase in 17:18. In that passage, God commanded Israel's kings to prepare "a copy of this law" for themselves. The Septuagint translators mistakenly rendered this phrase "this second [repeated] law." The Vulgate (Latin) translation, influenced by the Septuagint, translated the phrase "second law" as deuteronomium, from which "Deuteronomy" is a transliteration. The Book of Deuteronomy is, to some extent, however, a repetition to the new generation of the Law that God gave at Mt. Sinai. For example, about 50 percent of the "Book of the Covenant" (Exod. 20:23— 23:33) is paralleled in Deuteronomy.2 Thus God overruled the translators' error, and gave us a title for the book in English that is appropriate, in view of the contents of the book.3 1Meredith G. Kline, "Deuteronomy," in The Wycliffe Bible Commentary, p. -

If Not Empire, What? a Survey of the Bible

If Not Empire, What? A Survey of the Bible Berry Friesen John K. Stoner www.bible-and-empire.net CreateSpace December 2014 2 If Not Empire, What? A Survey of the Bible If Not Empire, What? A Survey of the Bible Copyright © 2014 by Berry Friesen and John K. Stoner The content of this book may be reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ International Standard Book Number: 978-0692344781 For Library of Congress information, contact the authors. Bible quotations unless otherwise noted are taken from the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Cover design by Judith Rempel Smucker. For information or to correspond with the authors, send email to [email protected] Bound or electronic copies of this book may be obtained from www.amazon.com. The entire content also is available in PDF format reader at www.bible-and-empire.net. For the sake of concordance with our PDF edition, the page numbering in this book begins with the title page. Published in cooperation with CreateSpace, DBA On-Demand Publishing, LLC December 2014 If Not Empire, What? A Survey of the Bible 3 *** Naboth owned a vineyard beside the palace grounds; the king asked to buy it. Naboth refused, saying, “This land is my ancestral inheritance; YHWH would not want me to sell my heritage.” This angered the king. Not only had Naboth refused to sell, he had invoked his god as his reason. -

The Story of Balaam

Primary Education www.GodsAcres.org Church of God Sunday School THE STORY OF BALAAM Numbers 21:21 — 24:25; 31:1-16 Deuteronomy 18:10; 23:4 As the people of honour" and to do whatever Balaam asked if he would Israel continued to trav- only come and curse Israel. Balaam's answer was, "If el toward Canaan, God Balak would give me his house full of silver and gold, gave them great victo- I cannot go beyond the word of the LORD my God, to ries over two mighty kings—Sihon (SAI-hon), king of do less or more." the Amorites (AM-uh-rights), and Og, king of Bashan That should have been the end of the story. How- (BAY-shuhn). Soon Israel came to the land of the Moa- ever, Balaam then asked the men to stay overnight to bites (MO-uh-bites). The people of Moab were afraid see what God would say. (Was he hoping that God of the Israelites, "because they were many." would change His mind?) That night God told Balaam, Balak (BAY-lak), the king of the Moabites, had a "If the men come to call thee, rise up, and go with plan. He sent messengers on a long journey to Pethor them; but yet the word which I shall say unto thee, that (peth-ORE), a distance of almost 400 miles. These shalt thou do." The next morning, Balaam got up, sad- messengers were to find a man by the name of Balaam dled his ass (donkey), and went with the Moabite men. -

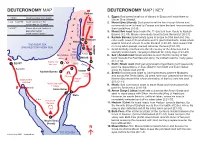

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan 1446 BC Israel’s exodus from Egypt 1. Egypt: God saves Israel out of slavery in Egypt and leads them to Mount Sinai (Horeb). 1446 - 1406 BC Israel wanders in the Edrei 2. Mount Sinai (Horeb): God gives Israel the law through Moses and wilderness for 40 years commands Israel to head to Canaan and take the land he promised to 1406 BC Moses dies and Joshua is their forefathers (1:6-8). appointed leader 3. Mount Seir road: Israel make the 11-day trek from Horeb to Kadesh Israel enters Canaan Barnea (1:2,19). Moses commands Israel to take the land (1:20-21). Jordan River 4. Kadesh Barnea: Israel sends spies to scope out the land and they 12 Hesbon return with news of its goodness and its giant inhabitants. Israel rebels Nebo 11 against God and refuses to enter the land (1:22-33). God swears that THE Great SEA no living adult (except Joshua) will enter the land (1:34-40). (THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA) 13 Salt Jahaz 5. Israel defiantly marches into the hill country of the Amorites and is CANAAN Sea soundly beaten back, camping in Kadesh for many days (1:41-45). Arnon 10 AMMON Ammorites (Dead 6. Seir | Arabah road: Israel wanders around the hill country of Seir Sea) MOAB back towards the Red Sea and along the Arabah road for many years Spying out 9 (2:1; 2:14). 1 5 EGYPT the land SEIR Zered 7. Elath | Moab road: God instructs Israel to head back north peacefully 6 past the descendants of Esau (Edom) from Elath and Ezion Geber Succoth 8 along the Moab road (2:2-8). -

Intertestamental Al Survey

INTERTESTAMENTAL AL SURVEY INTRODUCTION The 400 “Silent Years” between the Old and New Testaments were anything but “silent.” I. Intertestamental sources A. Jewish 1. Historical books of Apocrypha/Pseudepigrapha a. I Maccabees b. Legendary accounts: II & III Maccabees, Letter of Aristaeus 2. DSS from the I century B.C. a. “Manual of Discipline” b. “Damascus Document” 3. Elephantine papyri (ca. 494-400 B.C.; esp. 407) a. Mainly business correspondence with many common biblical Jewish names: Hosea, Azariah, Zephaniah, Jonathan, Zechariah, Nathan, etc. b. From a Jewish colony/fortress on the first cataract of the Nile (1)Derive either from Northern exiles used by Ashurbanipal vs. Egypt (2)Or from Jewish mercenaries serving Persian Cambyses c. The 407 correspondence significantly is addressed to Bigvai, governor of Judah, with a cc: to the sons of Sanballat, governor of Samaria. The Jews of Elephantine ask for aid in rebuilding their “temple to Yaho” that had been destroyed at the instigation of the Egyptian priests 4. Philo Judaeus (ca. 20 B.C.-40 A.D.) a. Neo-platonist who used allegory to synthesize Jewish and Greek thought b. His nephew, (Tiberius Julius Alexander), served as procurator of Judea (46-48) and as prefect of Egypt (66-70) INTERTESTAMENT - History - p. 1 5. Josephus (?) (ca. 37-100 a.d.) 73 a.d. a. History of the Jewish Wars (ca 168 b.c. – 70 a.d.) 93 a.d. b. Antiquities of the Jews: apparent access to the official biography of Herod the Great as well as Roman records B. Non-Jewish 1. Greek a. -

Unorthodox Jewish Beliefs Rabbi Steven Morgen, Congregation Beth Yeshurun

Unorthodox Jewish Beliefs Rabbi Steven Morgen, Congregation Beth Yeshurun SESSION THREE: WHO WROTE THE BIBLE? 1. Traditional view: Moses as “God’s Secretary” 2. The problems with Divine/Mosaic authorship: a. Genesis Chapter 1: Not good science! (Also have all the other miracles of the Bible: 10 Plagues, Parting the Sea, Sun stands still for Joshua, etc.) b. Anachronisms: “The Canaanites were then in the land,” “King Og’s Bed,” Moses saw “Dan,” Moses wrote “Moses died”? c. Contradictions and Parallel stories: Genesis Chapter 2 – contradicts Chapter 1! AND The Brothers Try to Kill Joseph – but who saves him?? d. Moses always referred to in 3rd person e. History of Language and Literature (Homer: The Iliad and The Odyssey – written down sometime between 8th and 6th century BCE – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homer ) 3. The “Un-Orthodox” view: Modern Biblical criticism a. First, a little history: Important Dates in Biblical History b. Documentary Hypothesis: J-E-P-D (See Richard Elliott Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible?) c. But if that is the case, what is the Torah’s authority? - 1 - DID MOSES WRITE THE ENTIRE TORAH? Subject Verses I. Anachronisms “Until today” Gen. 19:37,38/ 26:33/ Deut. 3:14/ 10:8/ 34:6 “the Canaanites were then in the Land” Gen. 12:6 (see Ibn Ezra)/ 13:7 “the land of the Hebrews” Gen. 40:15 King Og’s bed is still in “Rabba” Deut. 3:11 Who lived where, when? Deut. 2:10-12 Moses saw “Dan” ?? Deut. 34:1 (but wasn’t “Dan” until Judges 18:27-9!) Moses wrote “Moses died”? Deut. -

Baals of Bashan

RB.2014 - T. 121-4 (pp. 506-515). BAALS OF BASHAN BY Dr. Robert D. MILLER II, O.F.S. The Catholic University of America Washington, DC USA Department of Old Testament Studies University of Pretoria SOUTH AFRICA SUMMARY This essay argues that the phrase “Bulls of Bashan” is not about famous cattle but about cultic practice. Although this has been suggested before, this essay uses archaeology and climatology to show ancient Golan was no place for raising cattle. SOMMAIRE Cet essai fait valoir que l’expression « Taureaux de Basan » ne concerne pas les célèbres bovins mais des pratiques rituelles. Bien que cela ait été sug- géré auparavant, cet essai utilise archéologie et climatologie pour montrer que le Golan antique n’était pas un endroit pour l’élevage du bétail. The phrase “Bulls of Bashan” occurs twice in the Hebrew Bible (Ps 22:12; Ezek 39:18; cf. Jer 50:19), along with Amos 4:1’s mention of “Cows of Bashan.” The vast majority of commentators have under- stood this to refer to the “famous cattle” of Bashan, a region supposedly renowned for its beef or dairy production.1 I would like to challenge this 1 Thus, inter alia, Mitchell DAHOOD, Psalms AB (Garden City: Doubleday, 1979), 1.140; Klaus KOCH, TheProphets:TheAssyrianPeriod(Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983), 46; Avraham NEGEV, ed., ArchaeologicalEncyclopediaoftheHolyLand(New York: Continuum, 2005), s.v. “Bashan,” 68; Jonathan TUBB, TheCanaanites (Tulsa: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998), 91; Walter C. KAISER, HistoryofIsrael(Nashville: Broadman 997654_RevBibl_2014-4_02_Miller_059.indd7654_RevBibl_2014-4_02_Miller_059.indd 506506 222/09/142/09/14 111:301:30 BAALS OF BASHAN 507 interpretation, arguing not only that the phrase Bulls of Bashan refers not to the bovine but to the divine, but moreover that Iron Age Bashan would have been a terrible land for grazing and the last place to be famous for beef or dairy cattle. -

A Lament for Tyre and the King of Tyre

A Lamentation for Tyre and the King of Tyre Lesson 11: Ezekiel 27-28 November 10, 2019 Ezekiel Outline • 1-33 The wrath of the Lord GOD • 1-24 Oracles of wrath against Israel • 1-3 Revelation of God and • 25-32 Oracles of wrath against the commission of Ezekiel nations • 4-23 Messages of wrath for Jerusalem • 24-33 Messages of wrath during the • 33-48 Oracles of consolation for siege of Jerusalem Israel • 34-48 The holiness of the Lord GOD • 33-37 Regathering of Israel to the land • 34-39 The Restoration of Israel • 38-39 Removal of Israel’s enemies • 40-48 The restoration of the presence from the land of the Lord GOD in Jerusalem • 40-46 Reinstatement of true worship • 47-48 Redistribution of the land Then they will know that I am the LORD 4.5 • Distribution 4 • Significance 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 0.5 1.5 2.5 3.5 4.5 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11Israel 12 13 14 15 16 17 20 22 23 24 25 26 28 29 30 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 Israel Then they will know that IamtheLORD willknowthat Then they Israel Israel Israel Israel women of Israel Israel Israel Israel Israel nations Israel Israel Israel Israel Ammon Moab Philistia Tyre Israel Sidon Israel Egypt Egypt nations Egypt Israel Israel Edom Israel nations Israel nations nations Israel nations Gog judgment restoration Chapter 27 Outline • 1-11 Tyre’s former state • 12-25 Tyre’s customers • 26-36 Tyre’s fall Tyre’s former state • A lament for Tyre Ezekiel 27:1-5 • What God says versus what Tyre 1Moreover, the word of the LORD came says to me saying, 2“And you, son of man, take up a lamentation over Tyre; 3and say to Tyre, who dwells at the entrance • Perfect in beauty to the sea, merchant of the peoples to many coastlands, ‘Thus says the Lord GOD, “O Tyre, you have said, ‘I am perfect in beauty.’ 4“Your borders are in the heart of the seas; Your builders have perfected your beauty.