2017 Report and Recommendations for Improving Pennsylvania's Judicial Discipline System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Affidavit of Written Initial Uniformed Commercial Code Financing Statement Fixture Filing, Land and Commercial Lien

Moorish National Republic Federal Government ~ Societas Republicae Ea Al Maurikanos ~ Moorish Divine and National Movement of the World Northwest Amexem / Northwest Africa / North America / 'The North Gate' Affidavit of Written Initial Uniformed Commercial Code Financing Statement Fixture Filing, Land and Commercial Lien National Safe Harbor Program UCC § 9-521 whereby Nationals who file written UCC1 claims can file UCCs in any state. 28 Dhu al Hijjah 1438 [28 December 2018] To: PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF STATE aka COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA and all derivatives thereof PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF STATE C/O 401 NORTH ST RM 308 N OFC BLDG HARRISBURG, PA 17120-0500 (717) 787-6458 TOM WOLF d/b/a GOVERNOR OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA CORPORATION OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR 508 MAIN CAPITOL BUILDING HARRISBURG, PENNSYLVANIA 17120 Phone (717) 787-2500 Fax (717) 772-8284 MIKE STACK d/b/a LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA JOSH SHAPIRO d/b/a ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA EUGENE DEPASQUALE d/b/a AUDITOR GENERAL OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA JOE TORSELLA d/b/a STATE TREASURER OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA LESLIE S. RICHARDS d/b/a SECRETARY OF THE PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION LEO D. BAGLEY d/b/a EXECUTIVE DEPUTY SECRETARY OF THE PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION SUZANNE H. ITZKO d/b/a DEPUTY SECRETARY FOR ADMINISTRATION OF THE PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION KURT J. MYERS d/b/a DEPUTY SECRETARY FOR DRIVER & VEHICLE SERVICES OF THE PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION GEORGE W. MCAULEY JR., P.E. d/b/a DEPUTY SECRETARY FOR HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION OF THE PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION JENNIE GRANGER d/b/a DEPUTY SECRETARY FOR MULTIMODAL TRANSPORTATION OF THE PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION JAMES D. -

Dallas County Edition

GENERAL ELECTION TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 2018 LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS VOTERS GUIDE NON-PARTISAN... REALLY! DALLAS COUNTY EDITION INFORMATION ON VOTING REFERENDUMS BY MAIL CANDIDATE RESPONSES EARLY VOTING ON THE ISSUES THAT TIMES & LOCATIONS AFFECT YOU WHERE TO VOTE ALSO AVAILABLE ONLINE AT ON ELECTION DAY VOTE411.ORG pg. 2 County Elections Voters Guide for Dallas County Voters League of Women Voters of Dallas Helpful Information Websites Telephone Numbers Dallas County Elections Department DallasCountyVotes.org Dallas County Elections Department (214) 819-6300 Texas Secretary of State VoteTexas.gov Texas Secretary of State - Elections Division (800) 252-8683 League of Women Voters of Dallas LWVDallas.org League of Women Voters of Dallas (214) 688-4125 Dallas County Democratic Party DallasDemocrats.org League of Women Voters of Texas (512) 472-1100 Dallas County Libertarian Party LPDallas.org League of Women Voters of Irving (972) 251-3161 Dallas County Republican Party DallasGOP.org League of Women Voters of Richardson (972) 470-0584 About the Voters Guide Write-In Candidates The Voters Guide is funded and published by the League of Women Voters of Voters may write-in and vote for declared and approved write-in candidates. Dallas. The League of Women Voters is a non-partisan organization whose mis- Declared and approved candidates for this election were sent questionnaires sion is to promote political responsibility through the informed participation of for the Voters Guide and their responses will appear in this guide, but their all citizens in their government. The League of Women Voters does not support names will not be listed on the ballot. -

Guardianship Tracking

Issue 3, 2018 newsletter of the administrative office of pa courts Guardianship Tracking After careful research, design and development, Pennsylvania’s much-anticipated Guardianship Tracking System (GTS) is now live in almost every county. (continued on page 2) With the new Guardianship Tracking System, everyone wins After careful research, design and development, Pennsylvania’s much-anticipated Guardianship Tracking System (GTS) is now live in almost every county. Developed by AOPC/IT Court-appointed guardians of months, sometimes years. Among its and the Office of Elder incapacitated adults can now receive many benefits, the GTS will ensure that Justice in the Courts automatic reminders about important potential guardianship problems are under the direction filing dates and deadlines. They can identified and responded to quickly. and supervision of the file inventory forms and annual reports Advisory Council on online rather than having to go to Additionally, the GTS integrates Elder Justice in the Courts, the GTS their county courthouse to file reports guardian information into a statewide is a new web-based system in which manually. database rather than separate, guardians of adults of all ages, court individual county databases. staff, Orphans’ Court clerks and judges Historically, court staff in each county “This statewide collection of data will can file, manage, track and submit have been tasked with manually not only eliminate the potential for guardianship reports. scanning and filing guardians’ inventories and annual reports. an unsuitable guardian to relocate to The new system is designed with the However, the Elder Law Taskforce other counties, but will also generate goal of monitoring guardian activity noted in its final report to the Supreme information about guardianship trends in Pennsylvania while streamlining Court that the majority of Orphans’ that will help decision makers draft and improving the guardianship filing Court clerks reported that they do not laws and establish procedures to process. -

Pa. High Court Addresses Scope of the Environmental Rights Amendment

THE OLDEST LAW JOURNAL IN THE UNITED STATES 1843-2017 PHILADELPHIA, TUESDAY, JULY 25, 2017 VOL 256 • NO. 16 ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL LAW Pa. High Court Addresses Scope of the Environmental Rights Amendment BY TERRY R. BOSSERT TERRY R. BOSSERT is Special to the Legal the former chief There is no doubt counsel for the that the PEDF n June 20, the Pennsylvania Pennsylvania Supreme Court issued a sig- Department of decision will lead to Onificant and potentially far- Environmental more challenges to gov- reaching opinion in Pennsylvania Protection and a Environmental Defense Foundation (PEDF) principal in Post & Schell’s environmental ernment actions and v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 2017 practice group and co-chair of the firm’s challenges to legislation Pa. LEXIS 1393, No. 10 MAP 2015 shale resource practice group. He counsels or regulations relating to (June 20, 2017). While initial attention clients on environmental regulatory has been paid to the decision’s potential matters and compliance programs, the environment as dif- monetary impact via the use of oil and represents them in related litigation, and ferent stakeholders find gas lease funds, a more detailed analysis provides government relations counseling reveals that the longer lasting impact of and advocacy related to environmental different meanings in PEDF will be found in its pronounce- legislation and regulations in the the decision. ments on the scope of judicial review of commonwealth of Pennsylvania. He can government actions and, perhaps, impli- be reached at [email protected]. cating the separation of powers among resources, the commonwealth shall the three branches of the government. -

Descendants of Robert Mcclish On

Descendants of Robert McCLISH Sue McClish Melton Table of Contents .Descendants . of. Robert. McCLISH. 1. .Name . .and . Location. .Indexes . 220. Produced by: Sue McClish Melton, 1018 Whites Creek Pike, Nashville, Tennessee, 37207, 775/513/1719, [email protected], mcclish-family-history.blogspot.~ Descendants of Robert McCLISH 1-Robert McCLISH {MKK 2}1 was born in 1780 in Londonderry Twp, Bedford, PA and died in Jul 1860 in Nottingham, Wells County, Indiana at age 80. Robert married Lydia Sylvia THATCHER, daughter of Isaac THATCHER and Mary Elizabeth (THATCHER), on 24 Jan 1806 in , Columbiana County, Ohio.2 Lydia was born in 1790 in , Tuscarawas County, Ohio and died in 1814 in , Tuscarawas County, Ohio at age 24. They have three children: John M., Rachel, and Jas. 1830 US Census Noted events in their marriage were: • Alt Marriage: 16 Jun 1806, Columbiana County, Ohio. Information from Family Tree: From here and Back again owned by Sheila Sommerfeld Noted events in her life were: • She has conflicting death information of 1813. • 2-John M. McCLISH {MKK 12}3 was born in 1810 in , Tuscarawas County, Ohio and died on 25 Dec 1909 in Rudolph, Wood, Ohio at age 99. Another name for John was John McLEISH. Noted events in his life were: • He worked as a farmer.4 1850 Census John and Margaret McClish (1850) John married Margaret ROBERTSON,5 daughter of {MKK 12} and Unknown, in 1836 in , Beaver County, Pennsylvania. Margaret was born in 1816 in , , Ohio. Another name for Margaret was Mary (MCCLISH). They have ten children: Martha Jane, Lydia, Mary Ann, Elizabeth, Abraham, Rachel, Margaret, Robert, Appleline, and Nancy M. -

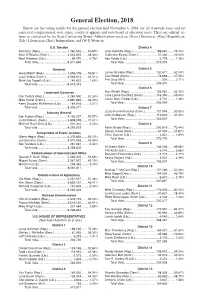

General Election, 2018

General Election, 2018 Below are the voting results for the general election held November 6, 2018, for all statewide races and for contested congressional, state senate, courts of appeals and state board of education races. These are official re- turns as canvassed by the State Canvassing Board. Abbreviations used are (Dem.) Democrat, (Rep.) Republican, (Lib.) Libertarian, (Ind.) Independent, and (W-I) Write-in. U.S. Senator District 4 Ted Cruz (Rep.) ............................... 4,260,553 ....... 50.89% John Ratcliffe (Rep.) ........................... 188,667 ....... 75.70% Beto O’Rourke (Dem.) ..................... 4,045,632 ....... 48.33% Catherine Krantz (Dem.)....................... 57,400 ....... 23.03% Neal Dikeman (Lib.) .............................. 65,470 ......... 0.78% Ken Ashby (Lib.) ..................................... 3,178 ......... 1.28% Total Vote .................................. 8,371,655 Total Vote ..................................... 249,245 Govenor District 5 Greg Abbott (Rep.) .......................... 4,656,196 ....... 55.81% Lance Gooden (Rep.) ......................... 130,617 ....... 62.34% Lupe Valdez (Dem.) ......................... 3,546,615 ....... 42.51% Dan Wood (Dem.) ................................. 78,666 ....... 37.55% Mark Jay Tippetts (Lib.) ...................... 140,632 ......... 1.69% Phil Gray (W-I) ........................................... 224 ......... 0.11% Total vote ................................... 8,343,443 Total Vote ..................................... 209,507 District -

Report on Regional Economies of Pennsylvania and COVID-19

SENATE MAJORITY POLICY COMMITTEE Senator David G. Argall (R-Schuylkill/Berks), Chairman REPORT ON REGIONAL ECONOMIES OF PENNSYLVANIA AND COVID-19 Senate Majority Policy Committee Report on Regional Economies of Pennsylvania and COVID-19 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... Page 1 The Safe Re-Opening of Western Pennsylvania’s Economy ........................................................ Page 2 Northeastern Pennsylvania’s Economy and COVID-19 ............................................................... Page 3 Southeastern Pennsylvania’s Economy and COVID-19 ............................................................... Page 4 Southcentral Pennsylvania’s Economy and COVID-19 ............................................................... Page 5 Our thanks to all who testified before the Senate Majority Policy Committee on this issue ........ Page 6 Introduction In March 2020, the first cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. On March 19, Governor Wolf ordered that all non-life sustaining businesses in the state needed to close physical locations in order to slow the spread of the virus. Those businesses that did not comply with the Governor’s mandate faced potential legal actions including citations, fines, and license suspensions. Many businesses applied for waivers to stay open during the shutdown and claims were solely handled by the Department of Community and Economic Development. -

L April 2014 CATEGORY: Militarv Retiree

DMVA Hall of Fame lnductee Nomination Form DATE: l April 2014 NAME oF INDUCTEE: Justice Seamus McCafferv CATEGORY: Militarv Retiree/ Government Executive - Retired Air Force Colonel, Current PA Supreme Court Justice TIME PERIOD: 1968 -20t4 JUSTIFICATION: Justice Mccaffery served 40 years in military service commencing in the U.S. Marine Corps in 1958 and retiring from the US Air Force Reserve in 2008. Justice Macaffery enlisted in the U. S. Marine Corps in 1968 and rose to the rank of Captain before leaving the Marine Corps and joining the US Air Force Reserve in 1985 where he rose to the rank of Colonel before his retirement. Justice Mccaffery is a 1977 graduate of Lasalle University and received hi J.D in 1989 from Temple University School of Law. He served in the Philadelphia Police Department for 20 years, was elected a Municipal Court Judge in philadelphia in 1993, appointed Administrative Judge of Municipal Court in 2003 and elected Judge of the PA Superior Court in 2003. Justice Mccaffery was elected a iustice of the supreme court of Pennsylvania in 2007. In his positions he worked tirelessly on the behalf of all Veterans. He is responsible for Pennsylvania having the largest and most successful Veterans Court program across the nation. Justice McCaffrey has many awards and honors to include: American Legion Man of the Year; Catholic War Veterans Man of the Year; Philadelphia Shomrim Fellowship Award; Pennsylvania Law Enforcement Hall of Fame; U. S. Air Force Reserves Squadron Commander ofthe Year; Air Force Security Police Commander of the Year to name a few. -

In Re Johnson & Johnson Talcum Powder Prods. Mktg., Sales

Neutral As of: May 5, 2020 7:00 PM Z In re Johnson & Johnson Talcum Powder Prods. Mktg., Sales Practices & Prods. Litig. United States District Court for the District of New Jersey April 27, 2020, Decided; April 27, 2020, Filed Civil Action No.: 16-2738(FLW), MDL No. 2738 Reporter 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 76533 * MONTGOMERY, AL; CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL PLACITELLA, COHEN, PLACITELLA & ROTH, PC, IN RE: JOHNSON & JOHNSON TALCUM POWDER RED BANK, NJ. PRODUCTS MARKETING, SALES PRACTICES AND PRODUCTS LITIGATION For ADA RICH-WILLIAMS, 16-6489, Plaintiff: PATRICIA LEIGH O'DELL, LEAD ATTORNEY, COUNSEL NOT ADMITTED TO USDC-NJ BAR, MONTGOMERY, AL; Prior History: In re Johnson & Johnson Talcum Powder Richard Runft Barrett, LEAD ATTORNEY, COUNSEL Prods. Mktg., Sales Practices & Prods. Liab. Litig., 220 NOT ADMITTED TO USDC-NJ BAR, LAW OFFICES F. Supp. 3d 1356, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 138403 OF RICHARD L. BARRETT, PLLC, OXFORD, MS; (J.P.M.L., Oct. 5, 2016) CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL PLACITELLA, COHEN, PLACITELLA & ROTH, PC, RED BANK, NJ. For DOLORES GOULD, 16-6567, Plaintiff: PATRICIA Core Terms LEIGH O'DELL, LEAD ATTORNEY, COUNSEL NOT ADMITTED TO USDC-NJ BAR, MONTGOMERY, AL; studies, cancer, talc, ovarian, causation, asbestos, PIERCE GORE, LEAD ATTORNEY, COUNSEL NOT reliable, Plaintiffs', cells, talcum powder, ADMITTED TO USDC-NJ BAR, PRATT & epidemiological, methodology, cohort, dose-response, ASSOCIATES, SAN JOSE, CA; CHRISTOPHER unreliable, products, biological, exposure, case-control, MICHAEL PLACITELLA, COHEN, PLACITELLA & Defendants', relative risk, testing, scientific, opines, ROTH, PC, RED BANK, [*2] NJ. inflammation, consistency, expert testimony, in vitro, causes, laboratory For TOD ALAN MUSGROVE, 16-6568, Plaintiff: AMANDA KATE KLEVORN, LEAD ATTORNEY, PRO HAC VICE, COUNSEL NOT ADMITTED TO USDC-NJ Counsel: [*1] For HON. -

Pdfaclu-PA Opposition to HB 38 PN 17 House

MEMORANDUM TO: Pennsylvania House Judiciary Committee FROM: Elizabeth Randol, Legislative Director, ACLU of Pennsylvania DATE: January 12, 2021 RE: OPPOSITION TO HOUSE BILL 38 P.N. 17 (DIAMOND) Background House Bill 38 (PN 17) is a proposed amendment to the Pennsylvania Constitution that would create judicial districts for the purpose of electing judges and justices to Pennsylvania’s appellate courts. While judges and justices on the Commonwealth, Superior, and Supreme Courts are currently elected at-large across the state, the proposed amendment would allow the legislature to draw geographic districts based on population. The stated reason for this amendment is to create a more geographically diverse judiciary and limit the number of judges and justices from Allegheny and Philadelphia counties.1 Proposed constitutional amendments must pass with identical language in two consecutive sessions. Having passed last session, if HB 38 passes for a second time this session, it could be placed on the ballot for ratification as early as the May primary. If approved by a simple majority vote of electors, it would become part of the Pennsylvania Constitution. On behalf of over 100,000 members and supporters of the ACLU of Pennsylvania, I respectfully urge you to oppose House Bill 38 (PN 17). Bill Summary House Bill 38 would: ■ Create seven districts for the election of Supreme Court justices, one for each justice on the Court; ■ Create judicial districts for the election of Superior Court judges, in a number determined by the 2 legislature; -

2017 Democratic Statewide Judicial Candidates Justice of the Supreme Court Judge Dwayne Woodruff: Judge on the Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas

2017 Democratic Statewide Judicial Candidates Justice of the Supreme Court Judge Dwayne Woodruff: Judge on the Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas. He was first elected to the court in 2005 and was retained in 2015. He graduated from the University of Louisville in 1979 and played defensive end for the Pittsburgh Steelers. He later earned his J.D. from Duquesne University School of Law in 1988. In 1997, Woodruff became a founding partner of the Woodruff, Flaherty & Fardo law firm. He also serves as the Pittsburgh co-chair for the National Campaign to Stop Violence’s “Do the Write Thing” Challenge Judge of the Superior Court – 4 open seats Judge Maria McLaughlin: Maria is a judge on the Philadelphia County Court of Common Pleas in Pennsylvania. She was elected in 2011, and her term expires in January 2022. McLaughlin received her bachelor’s degree from Pennsylvania State University in 1988 and her J.D. from Widener University School of Law in 1992. Judge Carolyn H. Nichols: Carolyn is a judge on the Philadelphia County Court of Common Pleas in Pennsylvania. Prior to her election to the common pleas court in 2011, Nichols held a number of positions, including legislative assistant to former Philadelphia Councilwoman Augusta Clarke, assistant city solicitor, and deputy secretary of external affairs for the office of the mayor of Philadelphia. Judge Debbie A. Kunselman: Deborah is a judge on the Beaver County Court of Common Pleas in Pennsylvania. She was elected in 2005 and was retained in 2015. She was the first female judge elected to the 36th district Court of Common Pleas. -

Evaluating the Need for Greater Federal Resources to Establish Veterans Courts Hearing Committee on the Judiciary United States

S. HRG. 111–589 EVALUATING THE NEED FOR GREATER FEDERAL RESOURCES TO ESTABLISH VETERANS COURTS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON CRIME AND DRUGS OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 1, 2010 Serial No. J–111–78 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 58–005 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 09:06 Sep 23, 2010 Jkt 058005 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\58005.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont, Chairman HERB KOHL, Wisconsin JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York JON KYL, Arizona RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois LINDSEY GRAHAM, South Carolina BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland JOHN CORNYN, Texas SHELDON WHITEHOUSE, Rhode Island TOM COBURN, Oklahoma AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota EDWARD E. KAUFMAN, Delaware ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania AL FRANKEN, Minnesota BRUCE A. COHEN, Chief Counsel and Staff Director MATT MINER, Republican Chief Counsel SUBCOMMITTEE ON CRIME AND DRUGS ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman HERB KOHL, Wisconsin LINDSEY GRAHAM, South Carolina DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois TOM COBURN, Oklahoma BENJAMIN L.