The Notion of Citizenship in Tony Kushner's Angels in America And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Normal Heart

THE NORMAL HEART Written By Larry Kramer Final Shooting Script RYAN MURPHY TELEVISION © 2013 Home Box Office, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold or distributed by any means or quoted or published in any medium, including on any website, without the prior written consent of Home Box Office. Distribution or disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is prohibited. Disposal of this script copy does not alter any of the restrictions previously set forth. 1 EXT. APPROACHING FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 1 Masses of beautiful men come towards the camera. The dock is full and the boat is packed as it disgorges more beautiful young men. NED WEEKS, 40, with his dog Sam, prepares to disembark. He suddenly puts down his bag and pulls off his shirt. He wears a tank-top. 2 EXT. HARBOR AT FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 2 Ned is the last to disembark. Sam pulls him forward to the crowd of waiting men, now coming even closer. Ned suddenly puts down his bag and puts his shirt back on. CRAIG, 20s and endearing, greets him; they hug. NED How you doing, pumpkin? CRAIG We're doing great. 3 EXT. BRUCE NILES'S HOUSE. FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 3 TIGHT on a razor shaving a chiseled chest. Two HANDSOME guys in their 20s -- NICK and NINO -- are on the deck by a pool, shaving their pecs. They are taking this very seriously. Ned and Craig walk up, observe this. Craig laughs. CRAIG What are you guys doing? NINO Hairy is out. -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

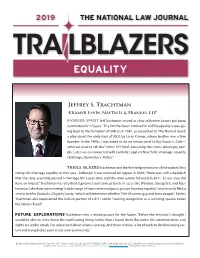

Equality Winner’S Name Here | Company Name

2019 THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL EQUALITY WINNER’S NAME HERE | COMPANY NAME Jeffrey S. Trachtman Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP Jeff Trachtman served as chair of Kramer Levin’s pro bono committee for 17 years. “The firm has been involved in LGBTQ equality issues go- ing back to the formation of GMHC, in 1981, as recounted in ‘The Normal Heart,’ a play about the early days of AIDS by Larry Kramer, whose brother was a firm founder. In the 1990s, I was asked to do an amicus brief in Boy Scouts v. Dale— what we used to call the ‘Homo 101’ brief, educating the courts about gay peo- ple. Later, we co-counseled with Lambda Legal on New York’s marriage equality challenge, Hernandez v. Robles.” Trachtman and the firm helped win one of the nation’s first rulings for marriage equality in that case. Although it was reversed on appeal in 2006, “there was such a backlash that the state assembly passed a marriage bill a year later, and the state senate followed in 2011. So our case did have an impact.” Trachtman has also filed Supreme Court amicus briefs in cases like Windsor, Obergefell, and Mas- terpiece Cakeshop representing “a wide range of mainstream religious groups favoring equality” and recently filed a similar brief in Bostock v. Clayton County, “which will determine whether Title VII covers gay and trans people.” Earlier, Trachtman also represented the lesbian partner of a 9/11 victim “seeking recognition as a surviving spouse under the Victims’ Fund.” Trachtman sees a mixed picture for the future. -

BOEING BOEING by Marc Camoletti Translated by Beverley Cross & Francis Evans

March 7 – April 2, 2017 on the OneAmerica Mainstage STUDY GUIDE edited by Richard J Roberts with contributions by Janet Allen • Laura Gordon Vicki Smith • Matthew LeFebvre • Charles cooper Indiana Repertory Theatre • 140 West Washington Street • Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Janet Allen, Executive Artistic Director • Suzanne Sweeney, Managing Director www.irtlive.com SEASON SPONSOR 2016-2017 SUPPORTERS 2 INDIANA REPERTORY THEATRE BOEING BOEING by Marc Camoletti translated by Beverley Cross & Francis Evans Paris has long been known as the city of love. However, in Bernard’s case, it is the city of interlocking flight schedules, an impeccable bachelor pad, and three well-vetted flight attendants who also happen to be his fiancées! In classic farcical tradition, Bernard and his American friend, Robert, hold on by the skin of their teeth as their affair is threatened with delayed flights and mistaken identity. In the tradition of early Roman comedy, Marc Camoletti offers his audience uproarious models of the knave, the fool, and the clever servant through Bernard, Robert, and Berthe. These three, accompanied by three foreign fiancées, present a whirlwind of slamming doors and romance while challenging and, ultimately, being reined in by the authority of monogamy. Student Matinee: March 22, 2017 Estimated length: 2 hours & 30 minutes THEMES & TOPICS Love and Marriage, Physical Comedy, Genre and Farce, European Culture CONTENT ADVISORY Boeing Boeing is a fun-filled farce that contains references to infidelity and mild sexual innuendo. Recommended -

HBO and the HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, the HISTORICAL FILM, and PUBLIC HISTORY at WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the Facul

HBO AND THE HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, THE HISTORICAL FILM, AND PUBLIC HISTORY AT WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University December 2016 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________________ Raymond J. Haberski, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________ Thorsten Carstensen, Ph.D. __________________________________ Kevin Cramer, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank the members of my committee for supporting this project and offering indispensable feedback and criticism. I would especially like to thank my chair, Ray Haberski, for being one of the most encouraging advisers I have ever had the pleasure of working with and for sharing his passion for film and history with me. Thorsten Carstensen provided his fantastic editorial skills and for all the times we met for lunch during my last year at IUPUI. I would like to thank Kevin Cramer for awakening my interest in German history and for all of his support throughout my academic career. Furthermore, I would like to thank Jason M. Kelly, Claudia Grossmann, Anita Morgan, Rebecca K. Shrum, Stephanie Rowe, Modupe Labode, Nancy Robertson, and Philip V. Scarpino for all the ways in which they helped me during my graduate career at IUPUI. I also thank the IUPUI Public History Program for admitting a Germanist into the Program and seeing what would happen. I think the experiment paid off. -

Clybourne Park Study Guide

Clybourne Park Study Guide The Theatre/Dance Department’s production oF Clybourne Park can be seen December 2 – 7 at 7:30 pm in Barnett Theatre. Tickets 262-472-2222 Monday – Friday 9:30 am – 5:00 pm The Clybourne Park Study Guide was originally created by Studio 180 Theatre, Toronto, Canada, and is being used at UW-Whitewater with Studio 180 Theatre’s permission. www.studio180theatre.com Table of Contents A. Notes for Teachers ...................................................................................................................... 3 B. Introduction to the Company and the Play .................................................................................. 4 UW-Whitewater Theatre/Dance Department .......................................................................................................... 4 Clybourne Park by Bruce Norris ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Bruce Norris – Playwright ................................................................................................................................................. 6 C. Attending the Performance ......................................................................................................... 7 D. Background Information ............................................................................................................. 8 1. Source Material: A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry ....................................................................... -

Community in August Wilson and Tony Kushner

FROM THE INDIVIDUAL TO THE COLLECTIVE: COMMUNITY IN AUGUST WILSON AND TONY KUSHNER By Copyright 2007 Richard Noggle Ph.D., University of Kansas 2007 Submitted to the Department of English and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ________________________ Chairperson, Maryemma Graham ________________________ Chairperson, Iris Smith Fischer ________________________ Paul Stephen Lim ________________________ William J. Harris ________________________ Henry Bial Date defended ________________ 2 The Dissertation Committee for Richard Noggle certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: FROM THE INDIVIDUAL TO THE COLLECTIVE: COMMUNITY IN AUGUST WILSON AND TONY KUSHNER Committee: ________________________ Chairperson, Maryemma Graham ________________________ Chairperson, Iris Smith Fischer ________________________ Paul Stephen Lim ________________________ William J. Harris ________________________ Henry Bial Date approved _______________ 3 ABSTRACT My study examines the playwrights August Wilson and Tony Kushner as “political” artists whose work, while positing very different definitions of “community,” offers a similar critique of an American tendency toward a kind of misguided, dangerous individualism that precludes “interconnection.” I begin with a look at how “community” is defined by each author through interviews and personal statements. My approach to the plays which follow is thematic as opposed to chronological. The organization, in fact, mirrors a pattern often found in the plays themselves: I begin with individuals who are cut off from their respective communities, turn to individuals who “reconnect” through encounters with communal history and memory, and conclude by examining various “successful” visions of community and examples of communities in crisis and decay. -

Multiculturalism and Transnational Formations in Tony Kushner's

Multiculturalism and Transnational Formations in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America Yvonne Iden Ngwa Higher Teacher Training School. (ENS) Yaoundé [email protected] Resum Multiculturalisme i formacions transnacionals a Angels in America de Tony Kushner En aquest article es vol demostrar que la representació del multiculturalisme ambient a Amèrica vist per Tony Kushner és palesa a la seva obra Angels in America a través de formacions transnacionals. La seva especificitat rau en el fet de recórrer els diferents aspectes del multiculturalisme. Les teories postcolonials i postmodernes posen de relleu l’heterogeneïtat que caracteritza les cultures a l’obra i justifiquen el multiculturalisme i el transnacionalisme. Paraules clau Multiculturalisme, formacions transnacionals, Tony Kushner. Resumen Multiculturalismo y formaciones transnacionales en Angels in America de Tony Kushner En este artículo, se quiere demostrar que la representación del multiculturalismo ambiente en América por Tony Kushner desemboca en formaciones transnacionales en su obra Angels in America. Lo que hace su especificidad es que recorre los distintos aspectos del multiculturalismo. Las teorías postcoloniales y postmodernas ponen de relieve la heterogeneidad que caracteriza las culturas en la obra y justifican el multiculturalismo y el transnacionalismo. Palabras clave Multiculturalismo, formaciones transnacionales, Tony Kushner. Résumé Multiculturalisme et formations transnationales dans Angels in America de Tony Kushner Dans cet article, on veut montrer que la représentation du multiculturalisme ambiant de l’Amérique par Tony Kushner aboutit à des formations transnationales dans sa pièce Angels in America. Contrairement aux autres articles qui décrivent généralement le multiculturalisme dont regorge la pièce, celui-ci s’intéresse aux différents contours de ce multiculturalisme ainsi qu’aux formations transnationales qui en découlent. -

Awake and Sing! Study Guide/Lobby Packett Prepared by Sara Freeman, Dramaturg

Awake and Sing! Study Guide/Lobby Packett Prepared by Sara Freeman, dramaturg Section I Clifford Odets: A Striving Life Clifford Odets was born in Philadelphia, on July 18, 1906, the son of a working-class Jewish family made good. Louis Odets, his father, had been a peddler, but also worked as a printer for a publishing company. In 1908, Louis Odets moved his family to New York City, where, after a brief return to Philadelphia, he prospered as a printer and ended up owning his own plant and an advertising agency, as well as serving as a Vice President of a boiler company. Odets grew up in the middle-class Bronx, not the Berger’s Bronx of tenements and squalor. Still Odets described himself as a “melancholy kid” who clashed often with his father. Odets quit high school after two years. When he was 17, Odets plunged into the theatre. He joined The Drawing Room Players and Harry Kemp’s Poets’ Theater. He wrote some radio plays, did summer stock, and hit the vaudeville circuit as “The Roving Reciter.” In 1929, he moved into the city because of a job understudying Spencer Tracy in Conflict on Broadway. A year later Odets joined the nascent Group Theatre, having met Harold Clurman and some of the other Group actors while playing bit parts at the Theatre Guild. The Group philosophy became the shaping force of Odets’ life as a writer. Clurman became his best friend and most perceptive critic. Odets wrote the first version of Awake and Sing!, then called I Got the Blues, in 1934. -

Christopher Durang

A LOOK AT SEASON SIXTY-SEVEN Colonial Players’ 2015-16 season will take our patrons on a journey from England to New York to Boston and from the late Victorian era to 21st-century America, using comedy, drama, and THE music to relate spellbinding tales of love, laughter, and, yes, even murder. Subscriptions for either five or seven shows will be on sale soon. We hope you will join us on our journey. ★ SEPTEMBER 4-26 The season opens with Sherlock’s Last Case, a ruefully comic send-up of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories about his famed English detective. This modern version is unlike anything you’ve seen about Holmes, with a jaw-dropping twist so unexpected we will ask our patrons not to reveal the secret to those who have yet to see the play. ★ OCTOBER 16-31 Side Man is a memory play told by a narrator who relates the story of his parents' relationship over four decades from the 1950s to the 1980s. It focuses on the lives of side men - musicians who made their living playing gigs with headliners on tours and in recording sessions - at a time when rock and roll was edging out jazz and big band music. Side Man won a Tony Award and was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize. Side Man contains strong language and mature themes. ★ NOVEMBER 20-DECEMBER 13 Morning's at Seven is a charming comedy set in the early 20th century and is the second in our series of classic American plays. Originally produced in 1938, it is a story of family relationships among four sisters, three husbands, and one son and his fiancée of 12 years. -

A Public University's Defense of Free Expression: the Issues and Events

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 327 894 CS 507 373 AUTHOR Smith, Ralph R.; Moore, DalP TITLE A Public University's Defense of Free Expression: The Issues and Events in the Staging of "The Normal Heart." PUB DATE Nov 90 NOTE 21p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association (76th, Chicago, IL, November 1-4, 1990). PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Freedom; Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrone; *Censorship; Discourse Analysis; *Freedom of Speech; Higher Education; *Homosexuality; Public Colleges; *School Community Relationship; *Theater Arts IDENTIFIERS First Amendment; *Normal Heart (Kramer); Rhetorical Strategies; 'Southwest Missouri State University ABSTRACT In 1989, some Springfield, Missouri residents demanded cancellation of the Southwest Missouri State University (SMSU) theater department's production of Larry Kramer's play, "The Normal Heart," which they allevd to be obscene. Opponents purchased newspaper advertisements which charged that the publicly funded production promoted a "homosexual, anti-family lifestyle." They held a rally, which attracted approximately 1,200 demonstrators. SMSU's attorney argued that the First Amendment barred cancellation ahsent substantial government interest, and asserted that the play was not obscene. Play opponents did not raise constitutional arguments, but suggested that freedom without commitment to moral order amounted to a "free-for-all." Some proponents of the production used the occasion to further AIDS education, while others labelled the play's critics as bigots. An arson incident brought national attention to the controversy and accusations from both sides in the dispute. The universi:4 formed a committee to oversee security for the play's performances.