Clean Cities 2015 Vehicle Buyer's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Gas Vehicles Myth Vs. Reality

INNOVATION | NGV NATURAL GAS VEHICLES MYTH VS. REALITY Transitioning your fleet to alternative fuels is a major decision, and there are several factors to consider. Unfortunately, not all of the information in the market related to heavy-duty natural gas vehicles (NGVs) is 100 percent accurate. The information below aims to dispel some of these myths while providing valuable insights about NGVs. MYTH REALITY When specifying a vehicle, it’s important to select engine power that matches the given load and duty cycle. Earlier 8.9 liter natural gas engines were limited to 320 horsepower. They were not always used in their ideal applications and often pulled loads that were heavier than intended. As a result, there were some early reliability challenges. NGVs don’t have Fortunately, reliability has improved and the Cummins Westport near-zero 11.9 liter engine enough power, offers up to 400 horsepower and 1,450 lb-ft torque to pull full 80,000 pound GVWR aren’t reliable. loads.1 In a study conducted by the American Gas Association (AGA) NGVs were found to be as safe or safer than vehicles powered by liquid fuels. NGVs require Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) fuel tanks, or “cylinders.” They need to be inspected every three years or 36,000 miles. The AGA study goes on to state that the NGV fleet vehicle injury rate was 37 CNG is not safe. percent lower than the gasoline fleet vehicle rate and there were no fuel related fatalities compared with 1.28 deaths per 100 million miles for gasoline fleet vehicles.2 Improvements in CNG cylinder storage design have led to fuel systems that provide E F range that matches the range of a typical diesel-powered truck. -

Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, and REPOWERS

What Fleets Need to Know About Alternative Fuel Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Acknowledgments This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 with Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, the Manager and Operator of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. This work was made possible through funding provided by National Clean Cities Program Director and DOE Vehicle Technologies Office Deployment Manager Dennis Smith. This publication is part of a series. For other lessons learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment (ARRA) projects, please refer to the following publications: • American Recovery and Reinvestment Act – Clean Cities Project Awards (DOE/GO-102016-4855 - August 2016) • Designing a Successful Transportation Project – Lessons Learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment Projects (DOE/GO-102017-4955 - September 2017) Authors Kay Kelly and John Gonzales, National Renewable Energy Laboratory Disclaimer This document is not intended for use as a “how to” guide for individuals or organizations performing a conversion, repower, or retrofit. Instead, it is intended to be used as a guide and resource document for informational purposes only. VEHICLE TECHNOLOGIES OFFICE | cleancities.energy.gov 2 ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Table of Contents Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................5 -

Fuel Cells on Bio-Gas

Fuel Cells on Bio-Gas 2009 Michigan Water Environment Association's (MWEA) Biosolids and Energy Conference Robert J. Remick, PhD March 4, 2009 NREL/PR-560-45292 NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. Wastewater Treatment Plants • WWTP operators are looking for opportunities to utilize biogas as a renewable energy source. • Majority use biogas through boilers for reheating • Interest is growing in distributed generation, especially where both electricity and fuel costs are high. • Drivers for the decision to purchase fuel cells – Reliability – Capital and O&M costs – Availability of Government Incentives National Renewable Energy Laboratory Innovation for Our Energy Future Anaerobic Digestion and Biogas • Anaerobic digestion is a process used to stabilize Range of Biogas Compositions wastewater sludge before final disposal. Methane 50% – 75% Carbon Dioxide 25% – 50% • The process uses Nitrogen 0% – 10% microorganisms in the Hydrogen 0% – 1% absence of oxygen to Sulfur Species 0% – 3% convert organic Oxygen 0% – 2% materials to biogas. National Renewable Energy Laboratory Innovation for Our Energy Future WWTP Co-Gen Market • There are over 16,800 WWTP in the U.S. • 615 facilities with flows > 3 mgd that use anaerobic digestion • 215 do not use their biogas but flare it instead. • California has the highest number of municipal facilities using anaerobic digestion, about 102, of which 25 do not use their biogas. -

Morgan Ellis Climate Policy Analyst and Clean Cities Coordinator DNREC [email protected] 302.739.9053

CLEAN TRANSPORTATION IN DELAWARE WILMAPCO’S OUR TOWN CONFERENCE THE PRESENTATION 1) What are alterative fuels? 2) The Fuels 3) What’s Delaware Doing? WHAT ARE ALTERNATIVE FUELED VEHICLES? • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THERE’S A FUEL FOR EVERY FLEET! DELAWARE’S ALTERNATIVE FUELS • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THE FUELS PROPANE • By-Product of Natural Gas • Compressed at high pressure to liquefy • Domestic Fuel Source • Great for: • School Busses • Step Vans • Larger Vans • Mid-Sized Vehicles COMPRESSED NATURAL GAS (CNG) • Predominately Methane • Uses existing pipeline distribution system to deliver gas • Good for: • Heavy-Duty Trucks • Passenger cars • School Buses • Waste Management Trucks • DNREC trucks PROPANE AND CNG INFRASTRUCTURE • 8 Propane Autogas Stations • 1 CNG Station • Fleet and Public Access with accounts ELECTRIC VEHICLES • Electricity is considered an alternative fuel • Uses electricity from a power source and stores it in batteries • Two types: • Battery Electric • Plug-in Hybrid • Great for: • Passenger Vehicles EV INFRASTRUCTURE • 61 charging stations in Delaware • At 26 locations • 37,000 Charging Stations in the United States • Three types: • Level 1 • Level 2 • D.C. Fast Charging TYPES OF CHARGING STATIONS Charger Current Type Voltage (V) Charging Primary Use Time Level 1 Alternating 120 V 2 to 5 miles Current (AC) per hour of Residential charge Level 2 AC 240 V 10 to 20 miles Residential per hour of and charge Commercial DC Fast Direct Current 480 V 60 to 80 miles (DC) per 20 min. -

Operation & Maintenance Manual E85 Compact Excavator

Operation & Maintenance Manual E85 Compact Excavator S/N B34T11001 & Above 6990616 (6-13) Printed in U.S.A. © Bobcat Company 2013 OPERATOR SAFETY WARNING Operator must have instructions before operating the machine. Untrained WARNING operators can cause injury or death. W-2001-0502 Safety Alert Symbol: This symbol with a warning statement, means: “Warning, be alert! Your safety is involved!” Carefully read the message that follows. CORRECT WRONG CORRECT WRONG P-90216 B-19792 B-19751 B-19754 Never operate without Do not grasp control Never operate without Avoid steep areas or instructions. handles when entering approved cab. banks that could break cab. away. Read machine signs, and Never modify equipment. Operation & Maintenance Be sure controls are in Manual, and Operator’s neutral before starting. Never use attachments Handbook. not approved by Bobcat Sound horn and check Company. behind machine before starting. WRONG WRONG CORRECT CORRECT Maximum Maximum MS-1784 MS1785 B-19756 MS-1786 Use caution to avoid Keep bystanders out of Never exceed a 15 slope Never travel up a slope tipping - do not swing maximum reach area. to the side. that exceeds 15. heavy load over side of track. Do not travel or turn with bucket extended. Operate on flat, level ground. Never carry riders. CORRECT CORRECT CORRECT CORRECT STOP Maximum TS-2068A NA-1435B 6808261 B-21928 NA-1421A Never exceed 25 when To leave excavator, lower Fasten seat belt securely. Look in the direction of going down or backing the work equipment and rotation and make sure up a slope. the blade to the ground. -

Fuel Properties Comparison

Alternative Fuels Data Center Fuel Properties Comparison Compressed Liquefied Low Sulfur Gasoline/E10 Biodiesel Propane (LPG) Natural Gas Natural Gas Ethanol/E100 Methanol Hydrogen Electricity Diesel (CNG) (LNG) Chemical C4 to C12 and C8 to C25 Methyl esters of C3H8 (majority) CH4 (majority), CH4 same as CNG CH3CH2OH CH3OH H2 N/A Structure [1] Ethanol ≤ to C12 to C22 fatty acids and C4H10 C2H6 and inert with inert gasses 10% (minority) gases <0.5% (a) Fuel Material Crude Oil Crude Oil Fats and oils from A by-product of Underground Underground Corn, grains, or Natural gas, coal, Natural gas, Natural gas, coal, (feedstocks) sources such as petroleum reserves and reserves and agricultural waste or woody biomass methanol, and nuclear, wind, soybeans, waste refining or renewable renewable (cellulose) electrolysis of hydro, solar, and cooking oil, animal natural gas biogas biogas water small percentages fats, and rapeseed processing of geothermal and biomass Gasoline or 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 1.12 B100 1 gal = 0.74 GGE 1 lb. = 0.18 GGE 1 lb. = 0.19 GGE 1 gal = 0.67 GGE 1 gal = 0.50 GGE 1 lb. = 0.45 1 kWh = 0.030 Diesel Gallon GGE GGE 1 gal = 1.05 GGE 1 gal = 0.66 DGE 1 lb. = 0.16 DGE 1 lb. = 0.17 DGE 1 gal = 0.59 DGE 1 gal = 0.45 DGE GGE GGE Equivalent 1 gal = 0.88 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 0.93 DGE 1 lb. = 0.40 1 kWh = 0.027 (GGE or DGE) DGE DGE B20 DGE DGE 1 gal = 1.11 GGE 1 kg = 1 GGE 1 gal = 0.99 DGE 1 kg = 0.9 DGE Energy 1 gallon of 1 gallon of 1 gallon of B100 1 gallon of 5.66 lb., or 5.37 lb. -

Comparison of Hydrogen Powertrains with the Battery Powered Electric Vehicle and Investigation of Small-Scale Local Hydrogen Production Using Renewable Energy

Review Comparison of Hydrogen Powertrains with the Battery Powered Electric Vehicle and Investigation of Small-Scale Local Hydrogen Production Using Renewable Energy Michael Handwerker 1,2,*, Jörg Wellnitz 1,2 and Hormoz Marzbani 2 1 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, University of Applied Sciences Ingolstadt, Esplanade 10, 85049 Ingolstadt, Germany; [email protected] 2 Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, School of Engineering, Plenty Road, Bundoora, VIC 3083, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Climate change is one of the major problems that people face in this century, with fossil fuel combustion engines being huge contributors. Currently, the battery powered electric vehicle is considered the predecessor, while hydrogen vehicles only have an insignificant market share. To evaluate if this is justified, different hydrogen power train technologies are analyzed and compared to the battery powered electric vehicle. Even though most research focuses on the hydrogen fuel cells, it is shown that, despite the lower efficiency, the often-neglected hydrogen combustion engine could be the right solution for transitioning away from fossil fuels. This is mainly due to the lower costs and possibility of the use of existing manufacturing infrastructure. To achieve a similar level of refueling comfort as with the battery powered electric vehicle, the economic and technological aspects of the local small-scale hydrogen production are being investigated. Due to the low efficiency Citation: Handwerker, M.; Wellnitz, and high prices for the required components, this domestically produced hydrogen cannot compete J.; Marzbani, H. Comparison of with hydrogen produced from fossil fuels on a larger scale. -

Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric

Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks∗ Guang Wang Xiuyuan Chen Fan Zhang Rutgers University Rutgers University Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced [email protected] [email protected] Technology, CAS [email protected] Yang Wang Desheng Zhang University of Science and Rutgers University Technology of China [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT CCS CONCEPTS Due to the ever-growing concerns on the air pollution and • Networks → Network measurement; Mobile networks; energy security, many cities have started to update their Cyber-physical networks. taxi fleets with electric ones. Although environmentally friendly, the rapid promotion of electric taxis raises prob- KEYWORDS lems to both taxi drivers and governments, e.g., prolonged Electric vehicle; mobility pattern; charging pattern; evolving waiting/charging time, unbalanced utilization of charging experience; shared autonomous vehicle infrastructures and reduced taxi supply due to the long charg- ing time. In this paper, we make the first effort to understand ACM Reference Format: the long-term evolving patterns through a five-year study Guang Wang, Xiuyuan Chen, Fan Zhang, Yang Wang, and Desh- on one of the largest electric taxi networks in the world, i.e., eng Zhang. 2019. Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving the Shenzhen electric taxi network in China. In particular, Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks. In The 25th Annual we perform a comprehensive measurement investigation International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (Mo- called ePat to explore the evolving mobility and charging biCom ’19), October 21–25, 2019, Los Cabos, Mexico. ACM, New York, patterns of electric vehicles. -

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles?

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles? Many of us have likely considered an alternative fuel vehicle at some point in our lives. Balancing the positives and negatives is a tricky process and varies greatly based on our personal situations. However, many of the negatives that previously created hesitancy have changed in recent years. Below, we have outlined a few of the most commonly mentioned negatives regarding the two leading alternative fuel vehicle types: Flex Fuel vehicles and Electric/Hybrid vehicles. Then, you can decide for yourself whether one of these vehicle types are practical for you! Cost – How much does the vehicle cost to purchase and operate? Flex Fuel: Flex Fuel vehicles typically cost about the same as a gasoline vehicle.1 For fuel cost, E85 typically costs slightly less than gasoline, however, due to decreased efficiency has a slightly higher cost per mile than gasoline.2 Overall, a Flex Fuel vehicle is likely to be slightly more expensive than a gasoline counterpart. Electric/Hybrid: This situation varies quite a bit depending on where you live. Electric vehicles and hybrid vehicles often cost considerably more than a conventional gasoline vehicle. For example, a plug-in hybrid will cost around $4000-$8000 more than a conventional model.3 However, there are federal rebates and local rebates that can refund thousands of dollars from the purchase price. Electric/Hybrid vehicles also tend to save money on fuel, with the possibility of saving thousands of dollars over the lifetime of the vehicle.4 Whether these rebates and fuel cost savings will eventually account for the higher purchase price can be estimated with comparison tools. -

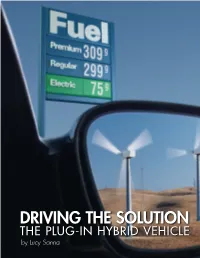

EPRI Journal--Driving the Solution: the Plug-In Hybrid Vehicle

DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna The Story in Brief As automakers gear up to satisfy a growing market for fuel-efficient hybrid electric vehicles, the next- generation hybrid is already cruis- ing city streets, and it can literally run on empty. The plug-in hybrid charges directly from the electricity grid, but unlike its electric vehicle brethren, it sports a liquid fuel tank for unlimited driving range. The technology is here, the electricity infrastructure is in place, and the plug-in hybrid offers a key to replacing foreign oil with domestic resources for energy indepen- dence, reduced CO2 emissions, and lower fuel costs. DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna n November 2005, the first few proto vide a variety of battery options tailored 2004, more than half of which came from Itype plugin hybrid electric vehicles to specific applications—vehicles that can imports. (PHEVs) will roll onto the streets of New run 20, 30, or even more electric miles.” With growing global demand, particu York City, Kansas City, and Los Angeles Until recently, however, even those larly from China and India, the price of a to demonstrate plugin hybrid technology automakers engaged in conventional barrel of oil is climbing at an unprece in varied environments. Like hybrid vehi hybrid technology have been reluctant to dented rate. The added cost and vulnera cles on the market today, the plugin embrace the PHEV, despite growing rec bility of relying on a strategic energy hybrid uses battery power to supplement ognition of the vehicle’s potential. -

Natural Gas Vehicle Technology

Natural Gas Vehicle Technology Basic Information about Light -Duty Vehicles History Natural Gas Vehicles 1910’s : Low-pressu re bag carried on a trailer (USA) 1930’s Wood-Gas (Germany) © ENGVA, 2003 1 Gaseous Vehicle Fuels LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas) Propane, butane, mixture 3 – 15 bar (45 – 625 psi) at ambient temperature CNG (Compressed Natural Gas) Methane CH 4 200 bar (3000 psi) at ambient temperature LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) Methane CH 4 Cryogenic : Liquefied at -162°C (typical for vehicle use -140°C @ 3 to 5 bar) H2 (Hydrogen) CH 2 (350 bar (5150 psi) compressed) or LH 2 (liquefied, -253°C) © ENGVA, 2003 CNG system overview Light-Duty Typical CNG Components in a Natural Gas Vehicle Fill receptacle Storage tank(s) Piping and fittings High Pressure Regulator Fuel-rail CNG injectors ECU Source : Volvo © ENGVA, 2003 2 CNG storage Storage in gaseous phase Storage under high pressure : 200 bar / 3000 psi Storage in one or more cylinders LPG storage Source : Barbotti, Argentina Storage in liquid phase Storage under low pressure : 3 - 15 bar Storage (mostly) in one cylinder Source : Opel © ENGVA, 2003 CNG fuel systems Light-Duty Mono-Fuel CNG only (dedicated) Bi-Fuel Source : Fiat Auto Spa CNG & Petrol © ENGVA, 2003 3 Mono-Fuel system Light-Duty Advantages Optimised engine possible Higher power output Lower fuel consumption Better exhaust gas emissions More available space for CNG tanks Better access to incentive programs Disadvantages Higher system price Restricted (total) range Dependency on filling station availability Source : -

Waste-To-Energy and Fuel Cell Technologies Overview

Innovation for Our Energy Future Waste-to-Energy and Fuel Cell ThTechnol ogi es O vervi ew Presented to: DOD-DOE Waste-to- Energy Workshop Dr. Robert J. Remick January 13, 2011 Capital Hilton Hotel Washington, DC NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. Global Approach for Using Biogas Innovation for Our Energy Future Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Wastes is a Good Source of Methane. Organic waste + methanogenic bacteria → methane (CH4) Issues: High levels of contamination Time varying output of gas quantity and quality Photo courtesy of Dos Rios Water Recycling Center, San Antonio, TX Innovation for Our Energy Future Opportunities for Methane Production via Anaerobic Digestion • Breweries (~73 Watts per barrel of beer) • Municipal Waste Water Treatment Plants (~4 W/person) • Industrial-scale Food Processing • Landfills • Dairy and Pig Farms (~200 W/Cow) • Pulp and Paper Mills Innovation for Our Energy Future Stationary Fuel Cell Products Currently on the Maaetrket aaere Confi gured to Oper ate on Natura l Gas UTC Power, Inc. PureCell 400 FlCllFuelCell EIEnergy Inc. DFC 300, 1500, an d 3000 Bloom Energy, Inc. ES-5000 Energy Server Waste processes that produce methane, like anaerobic digestion of organic matter, are most easily mated to these fuel cell systems. Innovation for Our Energy Future Comparison by Generator Type (based on 40-million SCF* of bioggpyas per year** ) Generator Type Megawatt‐hours/year PAFC 2,900 MCFC 3,300 Micro‐tbiturbine 1, 800 Reciprocating Engine 1,500 * ~830 Btu/SCF (HHV) ** WWTP serving a community of about 110,000 people This comparison ignores the fact that generators do not come in an infinite range of sizes.