Inter-Group Relations in Africa: the Amurri-Ugbawka Groups, to 1983

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Report of Yellow Fever Cases in 14 States Serial Number 010: Epi-Week 4 (As at 29 January 2021)

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Report of Yellow fever Cases in 14 States Serial Number 010: Epi-Week 4 (as at 29 January 2021) HIGHLIGHTS ▪ The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) is currently responding to reports of yellow fever cases in 14 states - Akwa Ibom, Bauchi, Benue, Borno, Delta, Ebonyi, Enugu, Gombe, Imo, Kogi, Osun, Oyo, Plateau and Taraba States From the 14 States ▪ In the last week (weeks 4, 2021) ‒ Four new confirmed cases were reported from National Reference Laboratory (NRL) from 2 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Benue - [Okpokwu (3), Ado (1) ‒ Thirteen presumptive positive cases were reported from NRL [Benue (6)] and Central Public Health Laboratory (CPHL) from [Enugu (6), Oyo (1)] ‒ One new LGA reported a confirmed case from Ado (1) in Benue State, ‒ No new death was recorded among confirmed cases ▪ Cumulatively from epi-week 24, 2020 – epi-week 4, 2021 ‒ A total of 1,502 suspected cases with 179 presumptive positive cases have been reported from 34 LGAs across 14 States from the Nigeria Laboratories ‒ Out of the 1,502 suspected, 161 confirmed cases [Delta-63 Ika North-East (48), Aniocha-South(6), Ika South (4), Oshimili South (2), Oshimili North(1), Ukwuani(1), Ndokwa West (1)], [Enugu-53 Enugu East (4), Enugu North (1), Igbo-Etiti (6), Igbo-Eze North(13), Isi-Uzo (15), Nkanu West (3) Nsukka(8), Udenu (3)], [Benue-17 (Ogbadibo (12), Okpokwu (4), Ado (1)], [Bauchi-9 Ganjuwa (8), Darazo (1)], [Borno-6 Gwoza(1), Hawul (1), Jere (2), Shani (1), Maiduguri (1)], [Ebonyi-3 Ohaukwu (3)], [Oyo-3), Ibarapa North East (1), Ibarapa North (2)], [Gombe-1 Akko (1)], [Imo-1 Owerri North(1)], [Kogi-1 Lokoja (1)], [Plateau- 1 Langtang North (1)], [Taraba-1 Jalingo (1)], [Akwa Ibom-1 Uyo(1)] and [Osun-1 Ilesha East (1)]. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Enugu State, Nigeria Out-Of-School Children Survey Report

ENUGU STATE, NIGERIA OUT-OF-SCHOOLCHILDREN SURVEY REPORT October, 2014 PREFACE The challenge of school-aged children who for one reason or another did not enrol in school at all or enrolled and later dropped out for whatever reason has been a perennial challenge to education the world over. Nigeria alone is said to house over 10 million out of school children. This is in spite of the universal basic education programme which has been running in the country since 1999. For Enugu State, it is not clear what the state contributes to that national pool of children who are reported to be out of school. Given the effort of the State Government in implementing the universal basic education programme, it is easy to assume that all children in Enugu State are enrolled and are attending school. This kind of assumption might not give us the benefit of knowing the true state of things as they relate to out-of-school children in our State. This is even more so given the State’s development and approval of the Inclusive Education Policy, which has increased the challenge of ensuring that every child of school age, no matter his or her circumstance of birth or residence, has access to quality education; hence, the need to be concerned even for only one child that is out of school. It is, therefore, in a bid to ascertain the prevalence of the incidence of children who are outside the school system, whether public or private, that the Ministry of Education and Enugu State Universal Basic Education Board collaborated with DFID-ESSPIN and other stakeholders to conduct the out of school children’s survey. -

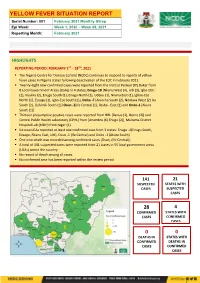

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 001 February 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: Week 1, 2020 – Week 08, 2021 Reporting Month: February 2021

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 001 February 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: Week 1, 2020 – Week 08, 2021 Reporting Month: February 2021 HIGHLIGHTS REPORTING PERIOD: FEBRUARY 1ST – 28TH, 2021 ▪ The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) continues to respond to reports of yellow fever cases in Nigeria states following deactivation of the EOC in February 2021. ▪ Twenty -eight new confirmed cases were reported from the Institut Pasteur (IP) Dakar from 8 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in 4 states; Enugu-18 [Nkanu West (4), Udi (3), Igbo-Etiti (2), Nsukka (2), Enugu South (1), Enugu North (1), Udenu (1), Nkanu East (1), Igboe-Eze North (1), Ezeagu (1), Igbo-Eze South (1)], Delta -7 [Aniocha South (2), Ndokwa West (2) Ika South (2), Oshimili South (1)] Osun -2[Ife Central (1), Ilesha - East (1) and Ondo-1 [Akure South (1)] ▪ Thirteen presumptive positive cases were reported from NRL [Benue (2), Borno (2)] and Central Public Health Laboratory (CPHL) from [Anambra (6) Enugu (2)], Maitama District Hospital Lab (MDH) from Niger (1) ▪ Six new LGAs reported at least one confirmed case from 3 states: Enugu -4(Enugu South, Ezeagu, Nkanu East, Udi), Osun -1 (Ife Central) and Ondo -1 (Akure South) ▪ One new death was recorded among confirmed cases [Osun, (Ife Central)] ▪ A total of 141 suspected cases were reported from 21 states in 55 local government areas (LGAs) across the country ▪ No record of death among all cases. ▪ No confirmed case has been reported within the review period 141 21 SUSPECTED STATES WITH CASES SUSPECTED CASES 28 4 -

Precipitants of Suicide Among Secondary School Students in Nigeria

Bassey Andah Jounal Vol. 9 PRECIPITANTS OF SUICIDE AMONG SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENTS IN NIGERIA Anthony ChukwuraUgwuoke Health Department Nkanu West LGA, Enugu state Abstract At the present, the rate at whichsuicide occurs among young persons in secondary schools in Nigeria is on the increase. Cases of suicide have been recorded among students in different parts of the country. Possible precipitants of suicide among the students were examined in this study. They were grouped into biopsychosocial, environmental and sociocultural factors. Some of these precipitants were inherent in the students themselves while the others emanated from their surroundings. The precipitants could act singly or in combination with others. The psychological and the sociological theories of suicide guided the explanation of the effects of the variables on the students in secondary schools in Nigeria. With a clearer picture of the precipitants of suicide among the students made, the researcher suggested that school health educators should explore every available moment to educate the students on suicide. He also advocated the design of suicide education programme to be implemented in the schools. Keywords: suicide, students, secondary school, suicide precipitants It is an illusion to believe that the problem of suicide is still that of the industrialized countries only. According to Clayton (2013), suicide is also a growing challenge in developing countries. Specifically, Ogunseye (2011) reported that suicide is a daunting problem in Nigeria. The most disturbing aspect of this ugly development is that students in secondary schools currently engage in it. Documented evidence in Nigeria revealed that younger individuals committed suicide more frequently than was the case in the past. -

Evaluation of Ground Water Potential Status in Nkanu-West Local Government Area, Enugu State, Nigeria

IOSR Journal of Applied Geology and Geophysics (IOSR-JAGG) e-ISSN: 2321–0990, p-ISSN: 2321–0982.Volume 4, Issue 6 Ver. I (Nov. - Dec. 2016), PP 58-66 www.iosrjournals.org Evaluation of Ground Water Potential Status in Nkanu-West Local Government Area, Enugu State, Nigeria *1Okonkwo A.C, 2Ezeh C.C and 3Amoke A.I 1,2Department of Geology and Mining, Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Enugu, Nigeria. 3Department of Geology, Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike, Abia State, Nigeria. Abstract: The Evaluation of the groundwater potential status in Nkanu-west Local government area of Enugu State has been undertaken. The project area lies within latitudes 060 25I 00IIN to 060 38I 00IIN and Longitudes 0070 13I 00IIE to 0070 24I 00IIE with an area extent of about 489.4sqkm, over two main geological formations. A total of Seventy-Eight Vertical Electrical Sounding (VES) were acquired, employing the Schlumberger configuration. Resistivity and thickness of aquiferous layers were obtained from the interpreted VES data. Contour variation maps of Apparent resistivity, depth, traverse resistance, Longitudinal conductance, Electrical conductivity, aquifer transmissivity and hydraulic conductivity were constructed. Computed aquifer transmissivity from VES data, indicates medium to low yield aquifer. The latter was used to evaluate the groundwater potential status. Two groundwater potential were mapped; the moderate and low potential zones. The various contour maps and groundwater potential zone map will serve as a useful guide for groundwater exploration in the study area. Keywords: Aquifer yield, Contour maps, Groundwater potential status, Resistivity, Transmissivity, Transverse resistance. I. Introduction Knowledge of groundwater potential status in regions is key useful guide to a successful groundwater exploration and abstraction. -

Niger Delta Budget Monitoring Group Mapping

CAPACITY BUILDING TRAINING ON COMMUNITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT & SHADOW BUDGETING NIGER DELTA BUDGET MONITORING GROUP MAPPING OF 2016 CAPITAL PROJECTS IN THE 2016 FGN BUDGET FOR ENUGU STATE (Kebetkache Training Group Work on Needs Assessment Working Document) DOCUMENT PREPARED BY NDEBUMOG HEADQUARTERS www.nigerdeltabudget.org ENUGU STATE FEDERAL MINISTRY OF EDUCATION UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION (UBE) COMMISSION S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Teaching and Learning 40,000,000 Enugu West South East New Materials in Selected Schools in Enugu West Senatorial District 2 Construction of a Block of 3 15,000,000 Udi Ezeagu/ Udi Enugu West South East New Classroom with VIP Office, Toilets and Furnishing at Community High School, Obioma, Udi LGA, Enugu State Total 55,000,000 FGGC ENUGU S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Construction of Road Network 34,264,125 Enugu- North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Enugu South 2 Construction of Storey 145,795,243 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Building of 18 Classroom, Enugu South Examination Hall, 2 No. Semi Detached Twin Buildings 3 Purchase of 1 Coastal Bus 13,000,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East Enugu South 4 Completion of an 8-Room 66,428,132 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Storey Building Girls Hostel Enugu South and Construction of a Storey Building of Prep Room and Furnishing 5 Construction of Perimeter 15,002,484 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Fencing Enugu South 6 Purchase of one Mercedes 18,656,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Water Tanker of 11,000 Litres Enugu South Capacity Total 293,145,984 FGGC LEJJA S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. -

Characteristics of Resistivity and Self-Potential Anomalies Over Agbani Sandstone, Enugu State, Southeastern Nigeria

Advances in Research 2(12): 730-739, 2014, Article no. AIR.2014.12.004 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Characteristics of Resistivity and Self-Potential Anomalies over Agbani Sandstone, Enugu State, Southeastern Nigeria Austin C. Okonkwo1* and Benard I. Odoh2 1Department of Geology and Mining, Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Enugu, Nigeria. 2Department of Geosciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Received 17th December 2014 th Original Research Article Accepted 28 January 2014 Published 8th July 2014 ABSTRACT The characteristics of the Resistivity and Self-Potential (SP) anomalies over Agbani Sandstone have been carefully and painstakingly carried out. The study was aimed at investigating the possible rock types and their mineralogical potentials. Data was acquired using the high resolution versatile ABEM SAS 4000 resistivity meter, employing the profiling method. Datasets were analyzed using the Excel toolkits. Interpretation was basically qualitative. Based on the resistivity interpretation, Agbani Sandstone is laterally limited in extent while the mineralization potential is high as a result of the high negative SP anomalies. The negative SP values range is -200mV to -500mV. This is practically indicative of a sulphide orebodies – possibly pyrite (FeS2). Comparative profile plots show that the observed zones of sulphide orebodies are within the gradational contact of Agbani Sandstone with Awgu Shale. Stream sediment analysis and rock geochemical study are recommended. However, the study has shown that contact zones of sandstone deposits are possibly ore enrichment zones. Keywords: Self-potential; resistivity; pyrite; Agbani sandstone; enrichment zone. -

Water Aid Nigeria Expression of Interest Wateraid Is a UK Registered

Water Aid Nigeria Expression of Interest WaterAid is a UK registered international charity dedicated to the provision of safe water, sanitation and hygiene to the world’s poorest people. WaterAid has worked in Nigeria since 1996 and partners with the government and people of Nigeria to develop sustainable access to water, sanitation and hygiene. We currently implement our programmes in 6 states- Benue, Jigawa, Plateau, Bauchi, Ekiti and Enugu States. Towards our programme implementation for the current year, WaterAid Nigeria hereby invites eligible companies to apply for pre-qualification as contractors for the Construction/rehabilitation of boreholes and institutional latrines in Igbo-Eze North, Udenu, Nkanu East, Igbo-Eze South and Igbo-Etiti Local Government of Enugu State. The engagement shall be an annual contract and shall be renewable at the end of each year based on performance. Pre-qualification Requirements Interested companies are required to submit the following:- (a) Certificate of incorporation as a company in Nigeria issued by the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC) (b) Documentary evidence describing similar assignments with verifiable proof including years of experience. (c) Detailed company profile providing information on office location, staff strength and equipment capacity. (e) Evidence of financial capability. Submission and Closing Date:- Two copies of the documents in a sealed envelope and clearly marked “Pro-qualification Documents” written at the top right hand side of the envelope should be submitted to:- Enugu State Small Town Unit, EN-RUWASSA 7th Floor, Old CCB building, OkparaAvenue, Beside EEDC, Enugu Enugu State C/O Christopher Ogbu Tel; 08083865425 The sealed envelope should be submitted at the above address not later than 4pm on 11thDecember, 2014. -

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 003 May 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: 18 – 21 As at 31St May 2021 Reporting Month: May 2021

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 003 May 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: 18 – 21 as at 31st May 2021 Reporting Month: May 2021 REPORTING MONTH: May 2021 HIGHLIGHTS REPORTING PERIOD: May 1ST – 31ST, 2021 ▪ The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) continues to monitor reports of yellow fever cases in Nigeria. ▪ A total of 96 suspected cases were reported from 66 Local Government Areas (LGAs) across 19 states: Akwa Ibom (1), Anambra (12), Bauchi (11), Bayelsa (5), Borno (17), Delta (6), Edo (2), Enugu (3), Imo (3), Kwara (6), Nasarawa (1), Niger (12), Ogun (2), Ondo (1), Osun (1), Oyo (3), Plateau (3), Taraba (3), Yobe (4). ▪ Total of eight presumptive positive samples were recorded from Central Public Health Laboratory (CPHL) Lagos (6) from three LGAs in three states; Anambra -1 [Idemili (1)], Delta-2 [Aniocha South (2), Enugu -3 (Nkanu East (2), Nkanu West (1)] and two from National Reference Laboratory (NRL), Borno -2[Hawul (1), Shani (1) ▪ Seven new confirmed cases confirmed at Institut Pasteur (IP) Dakar from; Anambra-1 [Onitsha North (1)], Enugu-3(Nkanu East (3), Imo-1 (Ideato (1), Niger -1[Munya (1) and Ondo -1(Ondo West (1)] ▪ One death (Imo State) was reported among all cases within the review period 96 19 SUSPECTED STATES WITH CASES SUSPECTED CASES 7 5 CONFIRMED STATES WITH CASES CONFIRMED CASES 0 0 DEATHS IN STATES WITH CONFIRMED DEATHS IN CASES CONFIRMED CASES CUMMULATIVE FOR 1st JANUARY– 31ST MAY, 2021 ▪ Cumulatively from 1 January - 31 May 2021, a total of 626 suspected cases have been reported from 34 states -

Enugu State Nigeria Erosion and Watershed

RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) Public Disclosure Authorized ENUGU STATE NIGERIA EROSION AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (NEWMAP) Public Disclosure Authorized FOR THE 9TH MILE GULLY EROSION SUB-PROJECT INTERVENTION SITE Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) ENUGU STATE NIGERIA EROSION AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (NEWMAP) FOR THE 9TH MILE GULLY EROSION SUB-PROJECT INTERVENTION SITE FINAL REPORT Submitted to: State Project Management Unit Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project (NEWMAP) Enugu State NIGERIA NOVEMBER 2014 Page | ii Resettlement Action Plan for 9th Mile Gully Erosion Site Enugu State- Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................................................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................................................... v LIST OF TABLES...................................................................................................................................................................... v LIST OF PLATES ...................................................................................................................................................................... v DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Nigeria – Enugu State – Village Kings – Ethnic Igbos – State Protection – Orun-Ekiti

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: NGA34743 Country: Nigeria Date: 24 April 2009 Keywords: Nigeria – Enugu State – Village kings – Ethnic Igbos – State protection – Orun- Ekiti This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. How are kings appointed at village level in Nigeria? 2. What is their role? How much political influence and power do they have? 3. Is the position passed on to father and son only if the son has a son himself? If not, how is the position passed on? 4. [Deleted] 5. [Deleted] 6. Is Ekiti State still part of Nigeria? Who is the current Alara? 7. A brief update on the adequacy of state protection in Nigeria, particularly related to the effective (or otherwise) investigation and prosecution of serious crimes, such as murder. 8. Any relevant information about the Igwe ethnic group, such as whether it is predominant, whether there are any reports of discrimination against people of Igwe ethnicity, and whether local village kings have to be from a particular ethnicity. RESPONSE A map of Nigeria which indicates the locations of the states of Enugu, Ekiti and Lagos is provided as a general reference at Attachment 1 (United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations, Cartographic Section 2004, ‘Nigeria – Map No.