3 the Copyright Act 1968: Its Passing and Achievements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Landowner Property Defenses Against Eminent Domain

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 6-18-2021 Comparative Landowner Property Defenses Against Eminent Domain Thomas A. Oriet University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Oriet, Thomas A., "Comparative Landowner Property Defenses Against Eminent Domain" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 8611. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/8611 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. COMPARATIVE LANDOWNER PROPERTY DEFENSES AGAINST EMINENT DOMAIN by Thomas A. Oriet A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Faculty of Law in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Laws at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada © 2021 Thomas Oriet COMPARATIVE LANDOWNER PROPERTY DEFENSES AGAINST EMINENT DOMAIN by Thomas A. Oriet APPROVED BY: ______________________________________________ C. Trudeau Department of Economics ______________________________________________ B. -

Malawi Independence Act 1964 CHAPTER 46

Malawi Independence Act 1964 CHAPTER 46 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Fully responsible status of Malawi. 2. Consequential modifications of British Nationality Acts. 3. Retention of citizenship of United Kingdom and Colonies by certain citizens of Malawi. 4. Consequential modification of other enactments. 5. Judicial Committee of Privy Council. 6. Divorce jurisdiction. 7. Interpretation. 8. Short title. SCHEDULES : Schedule 1-Legislative Powers in Malawi. Schedule 2-Amendments not affecting the Law of Malawi. Malawi Independence Act 1964 CH. 46 1 ELIZABETH II 1964 CHAPTER 46 An Act to make provision for and in connection with the attainment by Nyasaland of fully responsible status within the Commonwealth. [ 10th June 1964] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- 1.-(1) On and after 6th July 1964 (in this Act referred to as Fully " the appointed day ") the territories which immediately before responsible protectorate status of the appointed day are comprised in the Nyasaland Malawi. shall together form part of Her Majesty's dominions under the name of Malawi ; and on and after that day Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom shall have no responsibility for the government of those territories. (2) No Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed on or after the appointed day shall extend or be deemed to extend to Malawi as part of its law ; and on and after that day the provisions of Schedule 1 to this Act shall have effect with respect to legislative powers in Malawi. -

(Repeal of the Copyright Act 1911) (Jersey) Order 2012

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). UK Statutory Instruments are not carried in their revised form on this site. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2012 No. 1753 COPYRIGHT The Copyright (Repeal of the Copyright Act 1911) (Jersey) Order 2012 Made - - - - 10th July 2012 Coming into force in accordance with article 1 It appears to Her Majesty that provision with respect to copyright has been made in the law of the Bailiwick of Jersey otherwise than by extending the provisions of Part 1 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988(1) to the Bailiwick of Jersey. Accordingly, Her Majesty, by and with the advice of Her Privy Council, in exercise of the powers conferred on Her by section 170 of, and paragraph 36(3) of Schedule 1 to, the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 makes the following Order: Citation and Commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Copyright (Repeal of the Copyright Act 1911) (Jersey) Order 2012 and comes into force on the day on which Part 1 of the Intellectual Property (Unregistered Rights) (Jersey) Law 2011(2) comes into force in its entirety. Repeal of the Copyright Act 1911 as it extends to Jersey 2. To the extent that it has effect in the Bailiwick of Jersey, the Copyright Act 1911(3) is repealed. Richard Tilbrook Clerk of the Privy Council (1) 1988 c.48. Amendments have been made to the 1988 Act but none are material for the purposes of this Order. (2) L.29/2011. (3) 1911 c.46. The 1911 Act was maintained in force in relation to Jersey by paragraph 41 of Schedule 7 to the Copyright Act 1956 (c.74) and when the 1956 Act was repealed, by paragraph 36(1) of Schedule 1 to the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

(Jersey) Law 2011 (Appointed Day) Act 201

STATES OF JERSEY r DRAFT INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (UNREGISTERED RIGHTS) (JERSEY) LAW 2011 (APPOINTED DAY) ACT 201- Lodged au Greffe on 30th October 2012 by the Minister for Economic Development STATES GREFFE 2012 Price code: B P.111 DRAFT INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (UNREGISTERED RIGHTS) (JERSEY) LAW 2011 (APPOINTED DAY) ACT 201- REPORT Overview The Intellectual Property (Unregistered Rights) (Jersey) Law 2011 was adopted by the States on 1st December 2010, sanctioned by Order of Her Majesty in Council on 16th November 2011 and registered in the Royal Court on 9th December 2011. Article 411(2) of the Law provides for it to come into force on such day or days as the States may appoint. The Draft Intellectual Property (Unregistered Rights) (Jersey) Law 2011 (Appointed Day) Act 201- will bring the whole of the Intellectual Property (Unregistered Rights) (Jersey) Law 2011 into force 7 days after the Act is adopted by the States. Background The Intellectual Property (Unregistered Rights) (Jersey) Law 2011 completely replaces and modernises current copyright law in the Island. The current law is provided by an extension to the Island of the UK Copyright Act 1911, an Act which has not provided copyright law in the UK since 1956. The Law also makes provision about other unregistered intellectual property rights. The provisions in the Law comply with major international conventions and treaties about unregistered intellectual property rights, and so the Law paves the way for Jersey to have the UK’s membership of these extended to the Island. Convention membership delivers automatic protection for the relevant creative content in all convention countries. -

The Engraving Copyright Acts in the Age of Enlightenment in England

International Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Studies Volume 5 Issue 12 ǁ December 2020 ISSN: 2582-1601 www.ijahss.com The Engraving Copyright Acts in the Age of Enlightenment in England Dominika Cora Department of History, Jagiellonian University Abstract : The beginnings of the copyright law date back to the Stationer's Company established in 1403. This group, initially referred to as the Guild of Stationers, was to be a guild of authors of texts, illuminators, bookbinders, and booksellers. The scope of its activities included writing, illumination, and book distribution, and later printing. The restriction of freedom and the control of published publications led to certain social divisions, to which the Statute of Queen Anne of 1710, was a reaction. The article analyses the regulations concerning the authors' copyright, which were first regulated in The Engraving Copyright Acts, of 1735, 1767, and 1777. The content of the analysis of all legal acts described was selected from the original acts, which were obtained during the search in the archives of the British Parliament. Their transcriptions are found in the Appendixes. Keywords : copyright, copyright law, England, engraving, law, mezzotint I. INTRODUCTION Great Britain is currently a hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary cabinet system. The formation of one’s own state system, based on the head of state, which was and is this monarchy, took several centuries. To describe the phenomenon related to publishing and publishing figures in eighteenth-century England, it is worth tracing the outline of the formation of this system. It influences the formation of one of the most important elements related to publishing and copyright. -

Copyright 2020 a Practical Cross-Border Insight Into Copyright Law

International Comparative Legal Guides Copyright 2020 A practical cross-border insight into copyright law Sixth Edition Published by Global Legal Group, in association with Bird & Bird LLP Featuring contributions from: Acapo AS Fross Zelnick Lehrman & Zissu, P.C. Simba & Simba Advocates Anderson Mōri & Tomotsune Grupo Gispert SyCip Salazar Hernandez & Gatmaitan Armengaud & Guerlain Hamdan AlShamsi Lawyers & Legal Consultants Synch Advokat AB Bae, Kim & Lee LLC Hylands Law Firm Wenger Plattner Baptista, Monteverde & Associados, Sociedade Klinkert Rechtsanwälte PartGmbB Wintertons Legal Practitioners de Advogados, SP, RL LexOrbis Bereskin & Parr LLP Liad Whatstein & Co. Berton Moreno + Ojam MinterEllison Bird & Bird LLP OFO VENTURA INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY & Daniel Law LITIGATION De Beer Attorneys Inc. PÉREZ CORREA & ASOCIADOS, S.C. De Berti Jacchia Franchini Forlani Studio Legale Semenov&Pevzner Deep & Far Attorneys-at-Law Shin Associates ICLG.com Table of Contents Expert Chapter 1 The DSM Directive: A Significant Change to the Regulation of Copyright Online Phil Sherrell & William Wortley, Bird & Bird LLP Country Q&A Chapters 5 Argentina 100 Norway Berton Moreno + Ojam: Marcelo O. García Sellart Acapo AS: Espen Clausen & Alexander Hallingstad 10 Australia 104 Philippines MinterEllison: John Fairbairn & Katherine Giles SyCip Salazar Hernandez & Gatmaitan: Vida M. Panganiban-Alindogan 17 Brazil Daniel Law: Hannah Vitória M. Fernandes & 111 Portugal Antonio Curvello Baptista, Monteverde & Associados, Sociedade de Advogados, SP, RL: Filipe Teixeira Baptista & Mariana Canada 23 Bernardino Ferreira Bereskin & Parr LLP: Catherine Lovrics & Naomi Zener Russia China 116 30 Semenov&Pevzner: Ksenia Sysoeva & Roman Lukyanov Hylands Law Firm: Erica Liu & Andrew Liu South Africa France 122 37 De Beer Attorneys Inc.: Elaine Bergenthuin & Claire Armengaud & Guerlain: Catherine Mateu Gibson 42 Germany Klinkert Rechtsanwälte PartGmbB: Piet Bubenzer & 128 Spain Dr. -

Laying the Foundation for Copyright Policy and Practice in Canadian Universities

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 11-29-2016 12:00 AM Laying the Foundation for Copyright Policy and Practice in Canadian Universities Lisa Di Valentino The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Samuel E. Trosow The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Library & Information Science A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Lisa Di Valentino 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Di Valentino, Lisa, "Laying the Foundation for Copyright Policy and Practice in Canadian Universities" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 4312. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4312 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Abstract Due to significant changes in the Canadian copyright system, universities are seeking new ways to address the use of copyrighted works within their institutions. While the law provides quite a bit of leeway for use of copyrighted materials for educational and research purposes, the response by Canadian universities1 and related associations has not been to fully embrace their legal rights – rather, they have taken an approach that places emphasis on risk avoidance rather than maximizing use of materials, unlike their American counterparts. In the U.S., where educational fair use is arguably less flexible in application than fair dealing, there is a higher level of copyright advocacy among professional associations, and several sets of best practices have been created to guide the application of copyright to educational use of materials. -

Seeing Visions and Dreaming Dreams Judicial Conference of Australia

Seeing Visions and Dreaming Dreams Judicial Conference of Australia Colloquium Chief Justice Robert French AC 7 October 2016, Canberra Thank you for inviting me to deliver the opening address at this Colloquium. It is the first and last time I will do so as Chief Justice. The soft pink tones of the constitutional sunset are deepening and the dusk of impending judicial irrelevance is advancing upon me. In a few weeks' time, on 25 November, it will have been thirty years to the day since I was commissioned as a Judge of the Federal Court of Australia. The great Australian legal figures who sat on the Bench at my official welcome on 10 December 1986 have all gone from our midst — Sir Ronald Wilson, John Toohey, Sir Nigel Bowen and Sir Francis Burt. Two of my articled clerks from the 1970s are now on the Supreme Court of Western Australia. One of them has recently been appointed President of the Court of Appeal. They say you know you are getting old when policemen start looking young — a fortiori when the President of a Court of Appeal looks to you as though he has just emerged from Law School. The same trick of perspective leads me to see the Judicial Conference of Australia ('JCA') as a relatively recent innovation. Six years into my judicial career, in 1992, I attended a Supreme and Federal Courts Judges' Conference at which Justices Richard McGarvie and Ian Sheppard were talking about the establishment of a body to represent the common interests and concerns of judges, to defend the judiciary as an institution and, where appropriate, to defend individual judges who were the target of unfair and unwarranted criticisms. -

Intellectual-Property Laws in the Hong Kong S.A.R.: Localization and Internationalization Paul Tackaberry"

Intellectual-Property Laws in the Hong Kong S.A.R.: Localization and Internationalization Paul Tackaberry" In preparation for the handover, Hong Kong en- En vue de la r6trocession, l'ancien conseil 16gis- acted local ordinances in the areas of patents, designs latif de Hong-Kong a adopt6 diverses ordonnances and copyright. A new Trade Marks Ordinance is ex- dans les domaines des brevets, du design et des droits pected after the handover. Interestingly, much of this d'auteurs. On s'attend 6galement . ce qu'une ordon- legislation is based on United Kingdom statutes. The nance sur les marques de commerce soit adoptde peu success of this legislation in safe-guarding intellectual- de temps apr~s la r6trocession. Plusieurs de ces textes property rights ("IPRs") will depend less upon its con- 16gislatifs sont bas6s sur le module anglais. Le succ~s tents, and more upon a clear separation of the state and de la protection des droits de propridt6 intellectuelle judiciary in the Special Administrative Region ddpendra toutefois moins du contenu de ces lois que de ("S.A.R.") of Hong Kong. Despite the absence of a la s6paration claire entre le systime judiciaire et l'tat 1997 CanLIIDocs 49 tradition of the formal protection of IPRs, China has dans la nouvelle Zone administrative sp6ciale de Hong- identified a need to enact comprehensive intellectual- Kong. Bien qu'elle n'ait pas de tradition de protection property legislation. However, the absence of Western- de Ia propri6t6 intellectuelle, la R6publique populaire style rule of law in China has contributed to foreign de Chine a reconnu la n6cessit6 d'adopter une 16gisla- dissatisfaction with the enforcement of IPRs. -

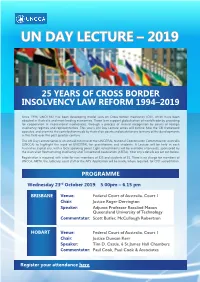

Un Day Lecture – 2019

UN DAY LECTURE – 2019 25 YEARS OF CROSS BORDER INSOLVENCY LAW REFORM 1994–2019 Since 1994, UNCITRAL has been developing model laws on Cross Border Insolvency (CBI), which have been adopted in Australia and most leading economies. These laws support globalisation of world trade by providing for cooperation in international insolvencies, through a process of mutual recognition by courts of foreign insolvency regimes and representatives. This year’s UN Day Lecture series will outline how the CBI framework operates, and examine the contribution made by Australian courts and practitioners to many of the developments in this field over the past quarter-century. The UN Day Lecture series is an annual initiative of the UNCITRAL National Coordination Committee for Australia (UNCCA) to highlight the work of UNCITRAL for practitioners and students. A Lecture will be held in each Australian capital city, with a local speaking panel. Light refreshments will be available afterwards, sponsored by the Australian Restructuring Insolvency and Turnaround Association (ARITA). Your city’s details are set out below. Registration is required, with a fee for non-members of $25 and students of $5. There is no charge for members of UNCCA, ARITA, the Judiciary, court staff or the APS. Application will be made, where required, for CPD accreditation. PROGRAMME Wednesday 23rd October 2019: 5.00pm – 6.15 pm BRISBANE Venue: Federal Court of Australia, Court 1 Chair: Justice Roger Derrington Speaker: Adjunct Professor Rosalind Mason Queensland University of Technology Commentator: Scott Butler, McCullough Robertson HOBART Venue: Federal Court of Australia, Court 1 Chair: Justice Duncan Kerr Speaker: Tim D. -

Centenary of Statutory Crown Copyright

CENTENARY OF STATUTORY CROWN COPYRIGHT Timeline Copyright Act 1911: Also known as the Imperial Copyright Act since it applied across the British Empire, with local adaptation as required. It brought together and rationalised the law on copyright which had previously been set out in many different statutes as well as previously being a part of the common law. It also enabled the UK to ratify the latest version of the Berne Convention, the principal (and at that time the only) international treaty on copyright. It came into force on 1 July 1912. References Enrolled statute (1&2 Geo 5 c46) in C 65/6288, see s18. Not freely available online. Treasury minute of 31 July 1912: This set out the terms for the publication of Crown copyright material by commercial companies. It drew attention to the fact that publication of any work by the Crown itself made that work Crown copyright. References T 243/10 Official War artists: At the beginning of both World Wars, many artists were commissioned to create artistic works relating to or inspired by the War. All such artists assigned their copyrights to the Crown. After the end of each War, the resulting works were distributed to galleries and museums in the UK and the Commonwealth. Recipient institutions in the UK were given delegated authority by the Controller of HMSO to license the use of the works they had received. References STAT 14/138 - There is a complete list of Second World War recipient institutions and works in T 162/744, file E40396/2 BBC v Wireless League Gazette Publishing [1926] LR Ch 433: In 1926, the BBC sued for infringement of its rights in the listings of radio programmes in the Radio Times. -

Megan Evetts CV 2019 Copy

Megan Evetts Barrister-at-law, Nigel Bowen Chambers Background and Practice Overview Megan has over nine years of litigation experience. She has predominantly practiced in intellectual property law, but also has experience in other areas of commercial and migration law. Prior to being called to the Bar, Megan was Associate to the Hon Justice Burley of the Federal Court of Australia. During that time, she had exposure to a wide variety of legal cases, in both first instance and appellate jurisdictions. This included intellectual property, admiralty, migration and general commercial law cases. Megan has also previously been a Senior Associate in MinterEllison’s intellectual property disputes team; in-house IP Counsel for a major international generic pharmaceutical company (Hospira, now Pfizer); and solicitor at King & Wood Mallesons. Megan has substantial experience in intellectual property litigation, intellectual property advisory work and patent and trade mark prosecution. Examples of significant cases that she has been involved in include the High Court appeal of AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd, regarding pharmaceutical patents for cholesterol drug rosuvastatin (Crestor); the first patent repair case in Australia, Seiko Epson Corporation v Calidad Pty Ltd; and the trade mark dispute Singtel Optus Pty Limited v Optum Inc. Megan is also a Trade Mark Attorney and holds a Bachelor of Biomedical Science and Bachelor of Laws (Hons) from Monash University. Admissions Barrister 2019 High Court of Australia 2012 Supreme Court of Victoria 2012 Professional Experience Federal Court of Australia Associate to the Hon Justice Burley 2018-2019 Sydney MinterEllison Senior Associate 2016-2018 Melbourne Associate 2014-2015 Lipman Karas Associate 2015-2016 Adelaide Hospira (now part of Pfizer) IP Legal Counsel 2014-2015 Melbourne (Secondee, then part-time employee) King & Wood Mallesons Solicitor 2012-2013 Melbourne Houlihan2 Trade Mark Attorney 2008-2012 Melbourne Technical Assistant Monash University, Physiology Dep.