Mcleod, Arise and Fall of the Kutch Bhayat 1 the RISE and FALL OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932'

EAST INDIA (CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS) REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932' Presented by the Secretary of State for India to Parliament by Command of His Majesty July, 1932 LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H^M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120, George Street, Edinburgh York Street, Manchester; i, St. Andrew’s Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1932 Price od. Net Cmd. 4103 A House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. The total cost of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) 4 is estimated to be a,bout £10,605. The cost of printing and publishing this Report is estimated by H.M. Stationery Ofdce at £310^ House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page,. Paras. of Members .. viii Xietter to Frim& Mmister 1-2 Chapter I.—^Introduction 3-7 1-13 Field of Enquiry .. ,. 3 1-2 States visited, or with whom discussions were held .. 3-4 3-4 Memoranda received from States.. .. .. .. 4 5-6 Method of work adopted by Conunittee .. .. 5 7-9 Official publications utilised .. .. .. .. 5. 10 Questions raised outside Terms of Reference .. .. 6 11 Division of subject-matter of Report .., ,.. .. ^7 12 Statistic^information 7 13 Chapter n.—^Historical. Survey 8-15 14-32 The d3masties of India .. .. .. .. .. 8-9 14-20 Decay of the Moghul Empire and rise of the Mahrattas. -

Bull. Zool. 8Ur". India, 6 (1-3) : 87-93, 1984 22-65

Bull. zool. 8ur". India, 6 (1-3) : 87-93, 1984 ECOLOGICAL STUDIES ON THE AMPHIBIANS OF GUJARAT A. K. SARKAR Zoological Survey of India., Oalcutta ABSTRACT The brief systematic account, details of material collected, geographical distribution, observa tions on the field ecology. food and association with other animals of nine species of amphibians (256 ex.) from Gujarat are discussed in the present paper. INTRODUCTION rashtra, Goa, West Bengal, South India and The amphibians of Gujarat are very little Sri Lanka. known in the Indian fauna. Even the funda Ecology: The frogs prefer to live in mental work of Boulenger (1890 and 1920) shallow muddy rain water tanks with muddy contains no information on the amphibians bottom and embankments. The vicinity of of Gujarat. Mc Cann (1938), Soman (1960) the above collection spots exhibited perfect and Daniel and Shull (1963) have published xeric environment and Pro8opi8 and Acacia short accounts on the amphibians from Kutch bushes were in abundance. As evidenced by area and Surat Dangs (Southern Gujarat) of the stomach contents the food of Rana hexa the State. So, this will be first detailed dactyla in the said localities during February account on the amphibians of the area. and March consists of large black ants Collections have mostly been made by Dr. Oamponotu8 sp. and various species of beetles. R. C. Sharma, Superintending Zoologist, Remarks: Porous warts on neck, under Zoological Survey of India. the thighs and along each side of belly are most prominent. The dorsal region of head SYSTEMATIC ACCOUNT and body is quite smooth and light olive-green Class : AMPHIBIA in colour. -

Cutch Or Random Sketches by Mrs. Postans - 1839; Copyright © 1 GEOGRAPHICAL POSITION of the PROVINCE of CUTCH

OR, RANDOM SKETCHES, TAKEN DURING A RESIDENCE IN ONE OF THE NORTHERN PROVINCES OF WESTERN INDIA; INTERSPERSED WITH LEGENDS AND CRADITIONS Reproduced by SANI H. PANHWAR (2020) CUTCH; OR , R A NDOM SKETCH ES, TA KEN DURING A RESIDENCEINONE OFTH E NORTH ERN PROV INCESOF W ESTER N INDIA ;INTERSPER SED W ITH Legends and CradItions B Y M R S.POSTA NS. 1839 ILLUSTRA TEDW ITH ENGRA V INGSFROM ORIGINA L DR A W INGS BYTHEA UTHOR. Reproduced by Sa niH .Panhw a r (2020) DURBAR HORSEMAN, In the service and pay of the Rao of Cutch. TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE JOHN FITZGIBBON, EARL OF CLARE, LATE GOVERNOR OF BOMBAY, &c., &c., &c. MY LORD, The honor your Lordship has conferred on me, by allowing your name to be prefixed to this unpretending volume, is highly flattering. For such a favor I should not have presumed to hope, had I not been aware of your Lordship's liberality of sentiment; the subject also being one with which your Lordship is well acquainted, and in which you have taken considerable interest. In this, my first attempt to place myself before the public in the responsible position of an author, many errors may probably be discovered, for which I feel convinced your Lordship will be disposed to entertain every generous indulgence. In the anxious hope, therefore, that, should the ensuing pages be found deficient in actual importance, they may offer something for the amusement of a few leisure hours, I have the honour to subscribe myself, With the highest respect, My Lord, Your Lordship's most grateful, Most obedient, Very humble Servant, MARIANNE POSTANS. -

3 Coin Festival

Auction 39 | 11 July 2015 World of Coins 3rd Coin Festival - Indore 2015 The Sponsors of 3rd Coin Festival – Indore 2015 Auction 39 World of Coins Saturday, 11th July 2015 7.00 pm onwards Sajan Prabha Garden Vijaynagar Square, Indore VIEWING (all properties) Thursday 2 July 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Friday 3 July 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Saturday 4 July 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Monday 6 July 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday 7 July 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Category LOTS Wednesday 8 July 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Ancient Coins 1-27 At Rajgor’s SaleRoom Hindu Coins of Medieval India 28-59 605 Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, 144 JSS Road, Sultanate Coins of Islamic India 60-67 Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Coins of Mughal Empire 68-111 Coins of Independent Kingdoms 112-137 Friday 10 July 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Saturday 11 July 2015 11:00 am - 4:00 pm Princely States of India 138-223 At the Indore Venue European Powers in India 224-239 British India 240-255 DELIVERY OF LOTS Republic of India 256-260 Delivery of Auction Lots will be done from the Mumbai Office of the Rajgor’s. Foreign Coins 261-307 Tokens 308-318 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S For an overview of the process, see the Badges 319 Easy to buy at Rajgor’s Medals 320-331 CONDITIONS OF SALE Front cover: Lot 24 • Back cover: Lot 162 This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale and to Reserves To download the free Android App on your ONLINE CATALOGUE Android Mobile Phone, View catalogue and leave your bids online at point the QR code reader application on your www.Rajgors.com smart phone at the image on left side. -

Name Capital Salute Type Existed Location/ Successor State Ajaigarh State Ajaygarh (Ajaigarh) 11-Gun Salute State 1765–1949 In

Location/ Name Capital Salute type Existed Successor state Ajaygarh Ajaigarh State 11-gun salute state 1765–1949 India (Ajaigarh) Akkalkot State Ak(k)alkot non-salute state 1708–1948 India Alipura State non-salute state 1757–1950 India Alirajpur State (Ali)Rajpur 11-gun salute state 1437–1948 India Alwar State 15-gun salute state 1296–1949 India Darband/ Summer 18th century– Amb (Tanawal) non-salute state Pakistan capital: Shergarh 1969 Ambliara State non-salute state 1619–1943 India Athgarh non-salute state 1178–1949 India Athmallik State non-salute state 1874–1948 India Aundh (District - Aundh State non-salute state 1699–1948 India Satara) Babariawad non-salute state India Baghal State non-salute state c.1643–1948 India Baghat non-salute state c.1500–1948 India Bahawalpur_(princely_stat Bahawalpur 17-gun salute state 1802–1955 Pakistan e) Balasinor State 9-gun salute state 1758–1948 India Ballabhgarh non-salute, annexed British 1710–1867 India Bamra non-salute state 1545–1948 India Banganapalle State 9-gun salute state 1665–1948 India Bansda State 9-gun salute state 1781–1948 India Banswara State 15-gun salute state 1527–1949 India Bantva Manavadar non-salute state 1733–1947 India Baoni State 11-gun salute state 1784–1948 India Baraundha 9-gun salute state 1549–1950 India Baria State 9-gun salute state 1524–1948 India Baroda State Baroda 21-gun salute state 1721–1949 India Barwani Barwani State (Sidhanagar 11-gun salute state 836–1948 India c.1640) Bashahr non-salute state 1412–1948 India Basoda State non-salute state 1753–1947 India -

The Western Railway

April 18, 1953 ACC at the Centenary Exhibition The Western Railway EATURING a reinforced con crete arch bridge motif, the HE Western Railway, which F according to the then policy of rais design of the ACC stall provides a came into being on the 5th T ing of foreign capital under a system splendid example of the versatility November, 1951, consists of the old of guaranteed return. In fifty years of concrete as a building material. B B & C I Railway (small metre of development, the present shape The daring cantilever projections gauge lengths of which were subse and extent of the Broad Gauge por and the pierced concrete panelling quently transferred to the Northern tion of the Western Railway came are outstanding among the novel and North-Eastern Railways), the into being. A still later develop features of the stall. Saurashtra, Jaipur and Rajasthan ment of the Broad Gauge line was (Udaipur) Railways, the 16-mile the electrification of the Bombay The valuable contribution made section Marwar Junction to Phulad Suburban Section of about 40 route by the Cement Industry in the de of the Jodhpur Railway, and the miles. velopment of our Railway system is Narrow Gauge Cutch State line The Metre Gauge portion of the vividly depicted through a series of (72 miles), together with the re Western Railway had its beginning photographic panels showing the cently constructed and opened in the 7o's when the section Delhi- various uses of cement for railway Deesa-Gandhidham Section con Rewari, including Farukhanagar structures ranging from large span necting with the projected port of Salt Branch, was constructed, which bridges, city terminal stations to Kandla in Cutch. -

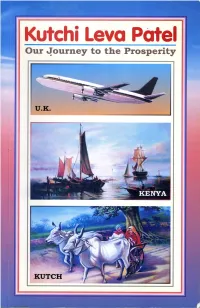

Kutchi Leva Patel Index Our Journey to the Prosperity Chapter Article Page No

Kutchi Leva Patel Index Our Journey to the Prosperity Chapter Article Page No. Author Shree S. P. Gorasia 1 Cutch Social & Cultural Society 10 First Published on: 2 Leva Patel Migration 14 Vikram Samvat – 2060 Ashadh Sood – 2nd (Ashadhi Beej) 3 Present Times 33 Date: 20th June 2004 4 Village of Madhapar 37 Second Published on: Recollection of Community Service Vikram Samvat – 2063 Ashadh Sood – 1st 5 Present Generation 55 Date: 15th July 2007 6 Kurmi-Kanbi - History 64 (Translated on 17 December 2006) 7 Our Kutch 77 Publication by Cutch Social and Cultural Society 8 Brief history of Kutch 81 London 9 Shyamji Krishna Varma 84 Printed by Umiya Printers- Bhuj 10 Dinbandhu John Hubert Smith 88 Gujarati version of this booklet (Aapnu Sthalantar) was 11 About Kutch 90 published by Cutch Social & Cultural Society at Claremont High School, London, during Ashadhi Beej celebrations on 12 Leva Patel Villages : 20th June 2004 (Vikram Savant 2060) with a generous support from Shree Harish Karsan Hirani. Madhapar 95 Kutchi Leva Patel Index Our Journey to the Prosperity Chapter Article Page No. Author Shree S. P. Gorasia 1 Cutch Social & Cultural Society 10 First Published on: 2 Leva Patel Migration 14 Vikram Samvat – 2060 Ashadh Sood – 2nd (Ashadhi Beej) 3 Present Times 33 Date: 20th June 2004 4 Village of Madhapar 37 Second Published on: Recollection of Community Service Vikram Samvat – 2063 Ashadh Sood – 1st 5 Present Generation 55 Date: 15th July 2007 6 Kurmi-Kanbi - History 64 (Translated on 17 December 2006) 7 Our Kutch 77 Publication by Cutch Social and Cultural Society 8 Brief history of Kutch 81 London 9 Shyamji Krishna Varma 84 Printed by Umiya Printers- Bhuj 10 Dinbandhu John Hubert Smith 88 Gujarati version of this booklet (Aapnu Sthalantar) was 11 About Kutch 90 published by Cutch Social & Cultural Society at Claremont High School, London, during Ashadhi Beej celebrations on 12 Leva Patel Villages : 20th June 2004 (Vikram Savant 2060) with a generous support from Shree Harish Karsan Hirani. -

2000 Port Expansion and Other Ancillary Services Apr18 to Sep18

APSEZ/EnvCell/2018-19/052 Date: 23.11.2018 To Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (C), Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Regional Office (WZ), E-5, Kendriya Paryavaran Bhawan, Arera Colony, Link Road No. – 3, Bhopal – 462 016. E-mail: [email protected] Sub : Half yearly Compliance report of Environment Clearance under CRZ notification for “Port expansion project including dry/break bulk cargo container terminal, railway link and related ancillary and back-up facilities at Mundra Port, Dist. Kutch in Gujarat by M/s. Adani Ports & SEZ Limited.” Ref : Environment clearance under CRZ notification granted to M/s Adani Ports & SEZ Limited vide letter dated 20th September, 2000 bearing no. J-16011/40/99-IA.III Dear Sir, Please refer to the above cited reference for the said subject matter. In connection to the same, it is to state that copy of the compliance report for the Environmental and CRZ Clearance for the period of April – 2018 to September – 2018 is enclosed here for your records. The stated information is also provided in form of a CD (soft copy). Thank you, Yours Faithfully, For, M/s Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Limited Avinash Rai Chief Executive Officer Mundra & Tuna Port Encl: As above Copy to: 1) The Director (IA Division), Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change, Indira Paryavaran Bhawan, Jor Bagh Road, New Delhi-110003 2) Zonal Officer, Regional Office, CPCB – Western Region, Parivesh Bhawan, Opp. VMC Ward Office No. 10, Subhanpura, Vadodara – 390 023 3) Member Secretary, GPCB – Head Office, Paryavaran Bhavan, Sector 10 A, Gandhi Nagar – 382 010 4) Deputy Secretary, Forests & Environment Department, Block – 14, 8th floor, Sachivalaya, Gandhi Nagar – 382 010 5) Regional Officer, Regional Office GPCB (Kutch-East), Gandhidham, 370201 Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Ltd Tel +91 2838 25 5000 Adani House, Fax +91 2838 25 51110 PO Box No. -

Ti>E Ln~·OA.A. ~£J ~~Wq:!W

Ti>e ln~·OA.A. ~£J ~~wq:!w ce~nfo-eKLe _ _jf?l a(lie 13bc;- .Petnivn- / . TIIE INDIAN STATES' PEOPLE'S CONFE~ENCE. REPORT OF THE BOMBAY SESSION. 17th, 18th December 1927. PUBLISHED BY Prof, G. R. ABHYANKAR, B. A., LL.B., General Secrlta,y, MANISHANKER S. TRIVEDI, B. A., Secretary. ""he Indian States' People's Conference, V 2. - 2. p Ashoka Building, Princess Street, F7 BOMBAY. Pri.uteil by B. M. Si<lhaye, at the Bombo.y Vaibhav Press, Servants of India Society's Home, Sandhurst Road, Girgaon, Bombay. 26th SeptembP.r 1928. ~\Jo nference :JJrnbay ..~~L.., INTRODUCTORY The Problem of Indian States, always difficult, has grown tremendously so in the years after the visit of the Montague Chelmsford mission to India. The estabHshment of the Princes' Cha:nber as .a direct result of this visit, and the repercussions of the introduction of elements of Responsible Government on the states as foreshadowed by the illustrious authors of the Reforms Report are the main causes that have aroused an intelligent and keen interest in the discussion of this Problem and created a demand for constitutional rule as well as a desire for participation in all matters of common interests with the pe.:>ple of Bri:isb India on the part of the people of the Indian States. This demand has increased with years, and signs are not wanting to show us the intensity as well as the earnestness that have inspired it. The People of the States have begun organising themselves by various rueanR. The establishment of the Deccan States Conference, the Kathiawar States Political Conference, the Rajputena Seva Sangha, and such other activities v:orking for the Political rights of the people of groups of Indian ~:tates, as well as Conferences of the people of individual States such as the Sangli State's People's C~nference, the Bhor Political Conference, the Bhavnagar Praja Parishad, the Cutchi Praja Parishad and tile Hyderabad State People's Conference, Janjira State Subjects Cou1erence, Miraj State People's Conference and the !dar Praja Parishad are the clear manifestations of the New Spirit that is abroad. -

Vol. III 1 Ch. 16-D PART D.—MISCELLANEOUS 1

Vol. III 1 Ch. 16-D PART D.—MISCELLANEOUS 1. It should be noted that section 54(1) seventhly, of Power of the Code of Criminal Procedure, authorises police officers Police to to arrest, without an order from a Magistrate and arrest without a warrant, persons liable under any law relating without warrant. to extradition or under the Fugitive Offenders Act, 1881, to apprehension or detention in British India on account of offences committed at any place out of British India. Such persons may, under sections 23 of the Extradition Act, 1903 be detained under the orders of a Magistrate, within the local limits of whose jurisdiction the arrest was made, in . the same manner and subject to the same restrictions as a person arrested on a warrant issued by such Magistrate under section 10. 1-A The following instructions have been issued by Provincial Government :— States which have agreed to It has been brought to the notice of the Punjab the procedure laid down as to Government that applications made by the Police of the requisition of India States for the arrest of fugitive offenders from Police for fugi- tives. their territories under the provisions of the seventh clause of section 54(1) of the Criminal Procedure Code are sometimes accompanied by no details which would assist the Magistrate before whom the alleged offender is produced to decide whether he should be released on bail or not. The Magistrate is thus placed in an un-satisfactory position when extradition is delayed and it is necessary (1) All states in the Punjab State to grant remands under section 344 of the Criminal Agency. -

The Durbar the Illustrations in This Volume Were Engraved and Printed at the Menpes Press Under the Superintendence of the Artist

mmmm r-r. THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES THE DURBAR THE ILLUSTRATIONS IN THIS VOLUME WERE ENGRAVED AND PRINTED AT THE MENPES PRESS UNDER THE SUPERINTENDENCE OF THE ARTIST AGENTS IN AMERICA THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 66 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK LORD CURZON IN HIS STUDY AT DELHI IN the face of many obstacles and predictions of failure, he organised and carried to a triumphant issue the celebration of the accession to the British throne of King Edward the Seventh. THE DURBAR * BY MORTIMER MENPES * TEXT BY DOROTHY MENPES PUBLISHED BY ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK-LONDON-W Published October 1903 if ^0 CONTENTS. PAGE 1. THE S.S. ARABIA ....... 3 2. SETTLING INTO CAMP . 19 3. THE STATE ENTRY . ..... 31 4. THE PROCLAMATION ... ... 53 5. THE PROCESSION OF RETAINERS . 71 6. THE REVIEW OF THE TROOPS ..... 99 7. THE PRESS CAMP . .... 113 8. THE RAJPUTANA CAMP . 123 9. THE PUNJAUB CAMP . 139 10. BARODA CAMP . .155 11. THE SIKKIM CAMP . .... 163 12. THE CENTRAL INDIA CAMP ... 169 13. THE BOMBAY AND IMPERIAL CADET CORPS. 177 14. THE VICEROY . .183 15. LORD KITCHENER . .... 195 16. REFLECTIONS 203 Vll LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Lord Curzon in his Study at Delhi . Frontispiece FACING PAGE 2. A Tailor 2 3. Late Afternoon ....... 4 4. A Blaze of Sun ....... 6 5. A Retainer from Rajgarh ...... 8 6. Away from the Show . ... 10 7. A Retainer of the Maharaja of Cutch . 12 8. A Street Scene . 14 9. A Distinguished Native Regiment . 16 10. A Retainer from Dhar ...... 18 11. Scene outside the Railway Station during the Delhi Durbar . -

IMPERIAL GAZETTEER of Indli\

THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDli\ VOL. XXVI ATLAS NEW EDITION PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIS MAJESTY 2 SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INDIA IN c(K~CIL OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS Hr:~R\ l'ROWDE, M t\ LOXDOX, EDI'<BURGII, NEW YORh TORC''iTO ,\XD \IU nOlJl<.i'lF ... PREFACE This Atlas has been prepared to accompany the new edition of The ImjJerzal Gazetteer of India. The ollgmal scheme was planned by Mr. W. S. Meyer, C.I.E., when editor for India, in co-operation with Mr. J S. Cotton, the editor in England. Mr. Meyer also drew up the lists of selected places to be inserted in the Provincial maps, which were afterwards verified by Mr. R. Burn, his suc cessor as editor for India. Great part of the materials (especially for the descriptive maps and the town plans) were supplied by the Survey of India and by the depart ments in India concerned. The geological map and that showing economical minerals were specially compiled by Sir Thomas Holland, K.C.I.E. The meteorological maps are based upon those compiled by the late Su' John Eliot, KC.I.E., for his Clzmatological Atlas of Indw The ethno logical map is based upon that compiled by Sir Herbel t Risley, KC.I.E., for the RejJort of tlte Comts of htdza, 1901. The two linguistic maps wele specially compiled by Dr. G. A. Grierson, C.I.E., to exlublt the latest results of the Linguistic Survey of India. The four historical sketch maps-~howing the relative extent of British, 1\1 uham madan, and Hindu power in 1765 (the year of the Dl\v;il1l grant), in 1805 (after Lord Wellesley), in ] 837 (the acces sion of Queen Victoria), and in 1857 (the Mutiny)-~-havc been compiled by the editor In England.