Inflammatory Transcriptome Profiling of Human Monocytes Exposed Acutely to Cigarette Smoke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulation of Cdc42 and Its Effectors in Epithelial Morphogenesis Franck Pichaud1,2,*, Rhian F

© 2019. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2019) 132, jcs217869. doi:10.1242/jcs.217869 REVIEW SUBJECT COLLECTION: ADHESION Regulation of Cdc42 and its effectors in epithelial morphogenesis Franck Pichaud1,2,*, Rhian F. Walther1 and Francisca Nunes de Almeida1 ABSTRACT An overview of Cdc42 Cdc42 – a member of the small Rho GTPase family – regulates cell Cdc42 was discovered in yeast and belongs to a large family of small – polarity across organisms from yeast to humans. It is an essential (20 30 kDa) GTP-binding proteins (Adams et al., 1990; Johnson regulator of polarized morphogenesis in epithelial cells, through and Pringle, 1990). It is part of the Ras-homologous Rho subfamily coordination of apical membrane morphogenesis, lumen formation and of GTPases, of which there are 20 members in humans, including junction maturation. In parallel, work in yeast and Caenorhabditis elegans the RhoA and Rac GTPases, (Hall, 2012). Rho, Rac and Cdc42 has provided important clues as to how this molecular switch can homologues are found in all eukaryotes, except for plants, which do generate and regulate polarity through localized activation or inhibition, not have a clear homologue for Cdc42. Together, the function of and cytoskeleton regulation. Recent studies have revealed how Rho GTPases influences most, if not all, cellular processes. important and complex these regulations can be during epithelial In the early 1990s, seminal work from Alan Hall and his morphogenesis. This complexity is mirrored by the fact that Cdc42 can collaborators identified Rho, Rac and Cdc42 as main regulators of exert its function through many effector proteins. -

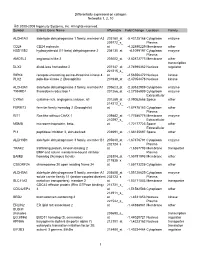

Differentially Expressed on Collagen Networks 1, 2, 10 © 2000-2009 Ingenuity Systems, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Symbol Entrez

Differentially expressed on collagen Networks 1, 2, 10 © 2000-2009 Ingenuity Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Symbol Entrez Gene Name Affymetrix Fold Change Location Family ALDH1A3 aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A3 203180_at -5.43125168 Cytoplasm enzyme 209772_s_ Plasma CD24 CD24 molecule at -4.32890229 Membrane other HSD11B2 hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 2 204130_at -4.1099197 Cytoplasm enzyme Plasma AMOTL2 angiomotin like 2 203002_at -2.82872773 Membrane other transcription DLX2 distal-less homeobox 2 207147_at -2.74996362 Nucleus regulator 221215_s_ RIPK4 receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 4 at -2.56556472 Nucleus kinase PLK2 polo-like kinase 2 (Drosophila) 201939_at -2.47054478 Nucleus kinase ALDH3A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, memberA1 205623_at -2.30532989 Cytoplasm enzyme TXNRD1 thioredoxin reductase 1 201266_at -2.27936909 Cytoplasm enzyme Extracellular CYR61 cysteine-rich, angiogenic inducer, 61 201289_at -2.09052668 Space other 214212_x_ FERMT2 fermitin family homolog 2 (Drosophila) at -1.87478183 Cytoplasm other Plasma RIT1 Ras-like without CAAX 1 209882_at -1.77586775 Membrane enzyme 210297_s_ Extracellular MSMB microseminoprotein, beta- at -1.72177723 Space other Extracellular PI3 peptidase inhibitor 3, skin-derived 203691_at -1.68135697 Space other ALDH3B1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, member B1 205640_at -1.67376791 Cytoplasm enzyme 202124_s_ Plasma TRAK2 trafficking protein, kinesin binding 2 at -1.6367793 Membrane transporter BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor Plasma BAMBI -

The Borg Family of Cdc42 Effector Proteins Cdc42ep1–5

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institute of Cancer Research Repository Biochemical Society Transactions (2016) 0 1–8 DOI: 10.1042/BST20160219 1 2 The Borg family of Cdc42 effector proteins 3 4 Cdc42EP1–5 5 6 Aaron J. Farrugia and Fernando Calvo 7 8 Tumour Microenvironment Team, Division of Cancer Biology, Institute of Cancer Research, 237 Fulham Road, London SW2 6JB, U.K. 9 Correspondence: Fernando Calvo ([email protected]) 10 11 12 13 Despite being discovered more than 15 years ago, the Borg (binder of Rho GTPases) 14 – family of Cdc42 effector proteins (Cdc42EP1 5) remains largely uncharacterised and rela- 15 tively little is known about their structure, regulation and role in development and disease. 16 Recent studies are starting to unravel some of the key functional and mechanistic 17 aspects of the Borg proteins, including their role in cytoskeletal remodelling and signal- 18 ling. In addition, the participation of Borg proteins in important cellular processes such as 19 cell shape, directed migration and differentiation is slowly emerging, directly linking Borgs 20 with important physiological and pathological processes such as angiogenesis, neuro- 21 fi transmission and cancer-associated desmoplasia. Here, we review some of these nd- 22 ings and discuss future prospects. 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Introduction 30 The Rho GTPase family member Cdc42 regulates a diverse range of cellular functions including cyto- 31 kinesis, cytoskeletal remodelling and cell polarity [1,2]. Like other Rho family members, Cdc42 cycles 32 between two tightly regulated conformational states, a GTP-bound active state and a GDP-bound 33 inactive state [3]. -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Dissection of the genomic structure of the miR-183/96/182 gene. Previously, we showed that the miR-183/96/182 cluster is an intergenic miRNA cluster, located in a ~60-kb interval between the genes encoding nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (Ube2h) on mouse chr6qA3.3 (1). To start to uncover the genomic structure of the miR- 183/96/182 gene, we first studied genomic features around miR-183/96/182 in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.UCSC.edu/), and identified two CpG islands 3.4-6.5 kb 5’ of pre-miR-183, the most 5’ miRNA of the cluster (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1 and Seq. S1). A cDNA clone, AK044220, located at 3.2-4.6 kb 5’ to pre-miR-183, encompasses the second CpG island (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cDNA clone was derived from 5’ exon(s) of the primary transcript of the miR-183/96/182 gene, as CpG islands are often associated with promoters (2). Supporting this hypothesis, multiple expressed sequences detected by gene-trap clones, including clone D016D06 (3, 4), were co-localized with the cDNA clone AK044220 (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). Clone D016D06, deposited by the German GeneTrap Consortium (GGTC) (http://tikus.gsf.de) (3, 4), was derived from insertion of a retroviral construct, rFlpROSAβgeo in 129S2 ES cells (Fig. 1A and C). The rFlpROSAβgeo construct carries a promoterless reporter gene, the β−geo cassette - an in-frame fusion of the β-galactosidase and neomycin resistance (Neor) gene (5), with a splicing acceptor (SA) immediately upstream, and a polyA signal downstream of the β−geo cassette (Fig. -

CHARACTERIZATION, EPIGENETIC DRUG EFFECT, and GENE DELIVERY to BREAST CANCER CELLS a Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Facu

CHARACTERIZATION, EPIGENETIC DRUG EFFECT, AND GENE DELIVERY TO BREAST CANCER CELLS A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Shan Lu December, 2015 CHARACTERIZATION, EPIGENETIC DRUG EFFECT, AND GENE DELIVERY TO BREAST CANCER CELLS Shan Lu Dissertation Approved: Accepted: Advisor Department Chair Dr. Vinod Labhasetwar Dr. Stephen Weeks Committee Chair Dean of the College Dr. Coleen Pugh Dr. John Green Committee Member Dean of Graduate School Dr. Abraham Joy Dr. Chand Midha Committee Member Dr. Ali Dhinojwala Committee Member Dr. Anand Ramamurthi Committee Member Dr. Peter Niewiarowski ii ABSTRACT Cancer relapse is strongly associated with the presence of cancer stem cells (CSCs), which drive the development of metastasis and drug resistance. In human breast cancer, CSCs are identified by the CD44+/CD24- phenotype and characterized by drug resistance, high tumorigenicity and metastatic potential. In this study, I found that MCF-7/Adr cells that are breast cancer cells resistant to doxorubicin (Dox) uniformly displayed CSC surface markers, possessed CSC proteins, formed in vitro mammospheres, yet retained low migratory rate. They were also able to self-renew and differentiate under floating culture condition and are responsive to epigenetic drug treatment. High degree of DNA methylation (modifications of the cytosine residues of DNA) and histone deacetylation are major epigenetic landmarks of CSCs. In this work, I showed that MCF-7/Adr cells are sensitive to histone deacetylation inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA). Through RNA-sequencing technology, I also found that decitabine (DAC) and SAHA similarly affected a large number of the examined pathways, including drug and nanoparticle cellular uptake and transport, lipid metabolism, carcinogenesis and nuclear transport pathways. -

Characterizing Humidity, Sex, and B-Cell Gene Regulation in Fungal Allergic

CHARACTERIZING HUMIDITY, SEX, AND B-CELL GENE REGULATION IN FUNGAL ALLERGIC ASTHMA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Emma Claire Kusick In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Department: Microbiological Sciences April 2020 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title CHARACTERIZING HUMIDITY, SEX, AND B-CELL GENE REGULATION IN FUNGAL ALLERGIC ASTHMA By EMMA KUSICK The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Dr. Jane Schuh Chair Dr. Teresa Bergholz Dr. Penelope Gibbs Dr. Sumit Ghosh Approved: 5/4/2020 Dr. John McEvoy Date Department Chair ABSTRACT Asthma is a debilitating lung disease that affects nearly 300 million people worldwide. Environments with high humidity and subsequent mold exposure often trigger allergic asthma. Sex differences have been reported in the incidence, prevalence, and severity of asthma. B-lymphocytes are recruited in high numbers to the allergic lung in response to the inhalation of Aspergillus fumigatus mold spores (conidia). In this work, we used a mouse model of allergic fungal asthma to assess environmental humidity, sex, and B-lymphocytes in an inhalational model of allergic fungal asthma. Our results showed that animals sensitized in low humidity conditions had no airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), inflammation, but an increase in IgG3 antibody production. Males weighed more than females, female mice had more fibrosis and produced more IgG3 Ab, but sex showed no impact on low humidity. -

CDC42EP4 (NM 012121) Human Tagged ORF Clone Product Data

OriGene Technologies, Inc. 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200 Rockville, MD 20850, US Phone: +1-888-267-4436 [email protected] EU: [email protected] CN: [email protected] Product datasheet for RC201162L3 CDC42EP4 (NM_012121) Human Tagged ORF Clone Product data: Product Type: Expression Plasmids Product Name: CDC42EP4 (NM_012121) Human Tagged ORF Clone Tag: Myc-DDK Symbol: CDC42EP4 Synonyms: BORG4; CEP4; KAIA1777 Vector: pLenti-C-Myc-DDK-P2A-Puro (PS100092) E. coli Selection: Chloramphenicol (34 ug/mL) Cell Selection: Puromycin ORF Nucleotide The ORF insert of this clone is exactly the same as(RC201162). Sequence: Restriction Sites: SgfI-MluI Cloning Scheme: ACCN: NM_012121 ORF Size: 1068 bp This product is to be used for laboratory only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. View online » ©2021 OriGene Technologies, Inc., 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200, Rockville, MD 20850, US 1 / 2 CDC42EP4 (NM_012121) Human Tagged ORF Clone – RC201162L3 OTI Disclaimer: The molecular sequence of this clone aligns with the gene accession number as a point of reference only. However, individual transcript sequences of the same gene can differ through naturally occurring variations (e.g. polymorphisms), each with its own valid existence. This clone is substantially in agreement with the reference, but a complete review of all prevailing variants is recommended prior to use. More info OTI Annotation: This clone was engineered to express the complete ORF with an expression tag. Expression varies depending on the nature of the gene. RefSeq: NM_012121.4 RefSeq Size: 3121 bp RefSeq ORF: 1071 bp Locus ID: 23580 UniProt ID: Q9H3Q1, B2R6D8 Domains: PBD MW: 38 kDa Gene Summary: The product of this gene is a member of the CDC42-binding protein family. -

Molecular Analyses of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma

Molecular Analyses of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Shir Kiong Lo National Heart and Lung Institute Imperial College Dovehouse Street London SW3 6LY A thesis submitted for MD (Res) Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London 2016 1 Abstract Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is an aggressive cancer that is strongly associated with asbestos exposure. Majority of patients with MPM present with advanced disease and the treatment paradigm mainly involves palliative chemotherapy and best supportive care. The current chemotherapy options are limited and ineffective hence there is an urgent need to improve patient outcomes. This requires better understanding of the genetic alterations driving MPM to improve diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic strategies. This research aims to gain further insights in the pathogenesis of MPM by exploring the tumour transcriptional and mutational profiles. We compared gene expression profiles of 25 MPM tumours and 5 non-malignant pleura. This revealed differentially expressed genes involved in cell migration, invasion, cell cycle and the immune system that contribute to the malignant phenotype of MPM. We then constructed MPM-associated co-expression networks using weighted gene correlation network analysis to identify clusters of highly correlated genes. These identified three distinct molecular subtypes of MPM associated with genes involved in WNT and TGF-ß signalling pathways. Our results also revealed genes involved in cell cycle control especially the mitotic phase correlated significantly with poor prognosis. Through exome analysis of seven paired tumour/blood and 29 tumour samples, we identified frequent mutations in BAP1 and NF2. Additionally, the mutational profile of MPM is enriched with genes encoding FAK, MAPK and WNT signalling pathways. -

Identification of Potential Pathogenic Genes Associated with Osteoporosis

610.BJBJR0010.1302/2046-3758.612.BJR-2017-0102 research-article2017 Freely available online OPEN ACCESS BJR RESEARCH Identification of potential pathogenic genes associated with osteoporosis Objectives B. Xia, Osteoporosis is a chronic disease. The aim of this study was to identify key genes in osteo- Y. Li, porosis. J. Zhou, Methods B. Tian, Microarray data sets GSE56815 and GSE56814, comprising 67 osteoporosis blood samples L. Feng and 62 control blood samples, were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in osteoporosis using Limma pack- Jining No. 1 People’s age (3.2.1) and Meta-MA packages. Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Hospital, Jining, Genomes enrichment analyses were performed to identify biological functions. Further- Shandong Province, more, the transcriptional regulatory network was established between the top 20 DEGs and China transcriptional factors using the UCSC ENCODE Genome Browser. Receiver operating char- acteristic (ROC) analysis was applied to investigate the diagnostic value of several DEGs. Results A total of 1320 DEGs were obtained, of which 855 were up-regulated and 465 were down- regulated. These differentially expressed genes were enriched in Gene Ontology terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways, mainly associated with gene expres- sion and osteoclast differentiation. In the transcriptional regulatory network, there were 6038 interactions pairs involving 88 transcriptional factors. In addition, the quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction result validated the expression of several genes (VPS35, FCGR2A, TBCA, HIRA, TYROBP, and JUND). Finally, ROC analyses showed that VPS35, HIRA, PHF20 and NFKB2 had a significant diagnostic value for osteoporosis. -

Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature Into Vascularized Glomeruli Upon Experimental Transplantation

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation † Sazia Sharmin,* Atsuhiro Taguchi,* Yusuke Kaku,* Yasuhiro Yoshimura,* Tomoko Ohmori,* ‡ † ‡ Tetsushi Sakuma, Masashi Mukoyama, Takashi Yamamoto, Hidetake Kurihara,§ and | Ryuichi Nishinakamura* *Department of Kidney Development, Institute of Molecular Embryology and Genetics, and †Department of Nephrology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan; ‡Department of Mathematical and Life Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan; §Division of Anatomy, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; and |Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST, Kumamoto, Japan ABSTRACT Glomerular podocytes express proteins, such as nephrin, that constitute the slit diaphragm, thereby contributing to the filtration process in the kidney. Glomerular development has been analyzed mainly in mice, whereas analysis of human kidney development has been minimal because of limited access to embryonic kidneys. We previously reported the induction of three-dimensional primordial glomeruli from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Here, using transcription activator–like effector nuclease-mediated homologous recombination, we generated human iPS cell lines that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the NPHS1 locus, which encodes nephrin, and we show that GFP expression facilitated accurate visualization of nephrin-positive podocyte formation in -

Network Organization of the Human Autophagy System

Vol 466 | 1 July 2010 | doi:10.1038/nature09204 ARTICLES Network organization of the human autophagy system Christian Behrends1, Mathew E. Sowa1, Steven P. Gygi2 & J. Wade Harper1 Autophagy, the process by which proteins and organelles are sequestered in autophagosomal vesicles and delivered to the lysosome/vacuole for degradation, provides a primary route for turnover of stable and defective cellular proteins. Defects in this system are linked with numerous human diseases. Although conserved protein kinase, lipid kinase and ubiquitin-like protein conjugation subnetworks controlling autophagosome formation and cargo recruitment have been defined, our understanding of the global organization of this system is limited. Here we report a proteomic analysis of the autophagy interaction network in human cells under conditions of ongoing (basal) autophagy, revealing a network of 751 interactions among 409 candidate interacting proteins with extensive connectivity among subnetworks. Many new autophagy interaction network components have roles in vesicle trafficking, protein or lipid phosphorylation and protein ubiquitination, and affect autophagosome number or flux when depleted by RNA interference. The six ATG8 orthologues in humans (MAP1LC3/GABARAP proteins) interact with a cohort of 67 proteins, with extensive binding partner overlap between family members, and frequent involvement of a conserved surface on ATG8 proteins known to interact with LC3-interacting regions in partner proteins. These studies provide a global view of the mammalian autophagy interaction landscape and a resource for mechanistic analysis of this critical protein homeostasis pathway. Protein homeostasis in eukaryotes is controlled by proteasomal turn- promote incorporation of Atg8p--PE into autophagosomes, allowing over of unstable proteins via the ubiquitin system and lysosomal turn- Atg8p to promote autophagosome closure and cargo recruitment. -

Shear Stress Modulates Gene Expression in Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2017 Shear Stress Modulates Gene Expression in Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts Zabinyakov, Nikita Zabinyakov, N. (2017). Shear Stress Modulates Gene Expression in Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27775 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/3639 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Shear Stress Modulates Gene Expression in Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts by Nikita Zabinyakov A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERING CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY 2017 © Nikita Zabinyakov 2017 Abstract Applied mechanical forces, such as those resulting from fluid flow, trigger cells to change their functional behavior or phenotype. However, there is little known about how fluid flow affects fibroblasts. The hypothesis of this thesis is that dermal fibroblasts undergo significant changes of expression of differentiation genes after exposure to fluid flow (or shear stress). To test the hypothesis, human dermal fibroblasts were exposed to laminar steady fluid flow for 20 and 40 hours and RNA was collected for microarray analysis.