Listening in Cyberspace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Security Analytics 8.1.X Reference Guide

Security Analytics 8.1.x Reference Guide Updated: Friday, November 15, 2019 Security Analytics Reference Guide Security Analytics 8.1 Copyrights, Trademarks, and Intellectual Property Copyright © 2019 Symantec Corp. All rights reserved. Symantec, the Symantec Logo, the Checkmark Logo, Blue Coat, and the Blue Coat logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Symantec Corp. or its affiliates in the U.S. and other countries. Other names may be trademarks of their respective owners. This document is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended as advertising. All warranties relating to the information in this document, either express or implied, are disclaimed to the maximum extent allowed by law. The information in this document is subject to change without notice. THE DOCUMENTATION IS PROVIDED "AS IS" AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED CONDITIONS, REPRESENTATIONS AND WARRANTIES, INCLUDING ANY IMPLIED WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE OR NON-INFRINGEMENT, ARE DISCLAIMED, EXCEPT TO THE EXTENT THAT SUCH DISCLAIMERS ARE HELD TO BE LEGALLY INVALID. SYMANTEC CORPORATION SHALL NOT BE LIABLE FOR INCIDENTAL OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES IN CONNECTION WITH THE FURNISHING, PERFORMANCE, OR USE OF THIS DOCUMENTATION. THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS DOCUMENTATION IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. SYMANTEC CORPORATION PRODUCTS, TECHNICAL SERVICES, AND ANY OTHER TECHNICAL DATA REFERENCED IN THIS DOCUMENT ARE SUBJECT TO U.S. EXPORT CONTROL AND SANCTIONS LAWS, REGULATIONS AND REQUIREMENTS, AND MAY BE SUBJECT TO EXPORT OR IMPORT REGULATIONS IN OTHER COUNTRIES. YOU AGREE TO COMPLY STRICTLY WITH THESE LAWS, REGULATIONS AND REQUIREMENTS, AND ACKNOWLEDGE THAT YOU HAVE THE RESPONSIBILITY TO OBTAIN ANY LICENSES, PERMITS OR OTHER APPROVALS THAT MAY BE REQUIRED IN ORDER TO EXPORT, RE-EXPORT, TRANSFER IN COUNTRY OR IMPORT AFTER DELIVERY TO YOU. -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Title MPOP Collection Vol.3, 400 Songs NR

NR. NO ARTIST A PICTURE OF ME (WITHOUT YOU) 50995 GEORGE JONES A WOMAN ALWAYS KNOWS 52017 DAVID HOUSTON AFRICA 08044 TOTO AFTER MIDNIGHT 06810 ERIC CLAPTON AFTER THE LOVIN' 06802 ENGELBERT HUMPERDINCK AIN'T THAT LONELY YET 50474 DWIGHT YOAKAM ALL FOR LOVE 06148 B.ADAMS / R.STEWART / STING ALL FOR YOU 07049 JANET JACKSON ALL I WANT 50161 TOAD THE WET SPROCKET ALL MY LIFE 52037 AMERICA ALL MY LOVING 06196 BEATLES ALL OUT OF LOVE 06042 AIR SUPPLY ALMOST PARADISE 06006 MIKE RENO & ANN WILSON ALWAYS 06328 BON JOVI AMANDA 52018 WAYLON JENNINGS AMAZED 50475 LONESTAR AMAZING GRACE 07152 JUDY COLLINS AND I LOVE HER 06198 BEATLES ANDANTE, ANDANTE 08141 ABBA ANNIE'S SONG 07112 JOHN DENVER ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE 50218 WILL YOUNG ANYTIME 50191 THE JETS ANYWHERE BUT HERE 50628 HILARY DUFF APRIL COME SHE WILL 50299 SIMON & GARFUNKEL ARE YOU EXPERIENCED? 52038 JIMI HENDRIX AUTUMN LEAVES 06091 ANDY WILLIAMS BABY 51782 ASHANTI BABY I'M A WANT YOU 09424 BREAD BAD 07427 MICHAEL JACKSON www.magic-sing.be Title MPOP Collection Vol.3, 400 songs NR. NO ARTIST BAD DAY 52091 FUEL BE 07506 NEIL DIAMOND BE MY BABY 07785 RONETTES BEAUTY AND THE BEAST 06487 CELINE DION / P.BRYSON BECAUSE I LOVE YOU 51736 PHIL COLLINS BECAUSE OF YOU 06013 98 DEGREES BEDTIME STORY 07974 TAMMY WYNETTE BELIEVE 06497 CHER BETTER CLASS OF LOSERS 52032 RANDY TRAVIS BIGGER THAN MY BODY 08186 JOHN MAYER BLACK CAT 51786 JANET JACKSON BLACK OR WHITE 07431 MICHAEL JACKSON BLACK SHEEP 50338 JOHN ANDERSON BLUE 50631 EIFFEL 65 BOOGIE WONDERLAND 50409 EARTH WIND & FIRE BOOGIE WOOGIE BUGLE BOY 09605 -

University of South Florida

Case Study www.ellacoya.com University of South Florida University of South Florida (USF), one of the top research universities in the US, is INTRODUCTION committed to formulating bold ideas and creating innovative solutions for its global community of 45,000 students, staff, and faculty. To provide its community with reliable, quality network service, USF needed an effective, flexible, and scalable way to prevent aggressive peer-to-peer (P2P) applications from using more than their fair share of bandwidth, to enable sophisticated control of individual abusers, and to support significant growth in traffic volumes. University of South Florida turned to Ellacoya’s IP Service Control System for an effective, flexible and scalable way to control bandwidth congestion in its network. As of late 2002, USF was experiencing significant network congestion due to P2P traffic. THE TRAFFIC CONTROL Its network was hit particularly hard by KaZaA 2.0, which USF’s enterprise-class PROBLEM appliance application could not reliably detect, and by a new P2P application its current firmware failed to detect at all. Network administrators also began to realize the limitations of application-based aggregate traffic management in the face of increasingly evasive emerging applications and the desirability of being able to enforce policies on specific individuals. Additionally, USF was in the process of upgrading its Internet connection to Gigabit speeds and needed a platform with the capacity for Gigabit throughput and the flexibility to scale with the university’s growing needs. Like many universities, USF had initially used an enterprise-class appliance to control EARLY ATTEMPTS TO P2P traffic, but the device was unable to consistently classify KaZaA traffic. -

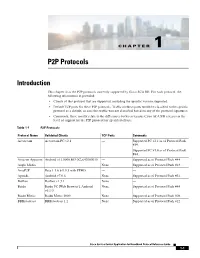

P2P Protocols

CHAPTER 1 P2P Protocols Introduction This chapter lists the P2P protocols currently supported by Cisco SCA BB. For each protocol, the following information is provided: • Clients of this protocol that are supported, including the specific version supported. • Default TCP ports for these P2P protocols. Traffic on these ports would be classified to the specific protocol as a default, in case this traffic was not classified based on any of the protocol signatures. • Comments; these mostly relate to the differences between various Cisco SCA BB releases in the level of support for the P2P protocol for specified clients. Table 1-1 P2P Protocols Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments Acestream Acestream PC v2.1 — Supported PC v2.1 as of Protocol Pack #39. Supported PC v3.0 as of Protocol Pack #44. Amazon Appstore Android v12.0000.803.0C_642000010 — Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. Angle Media — None Supported as of Protocol Pack #13. AntsP2P Beta 1.5.6 b 0.9.3 with PP#05 — — Aptoide Android v7.0.6 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #52. BaiBao BaiBao v1.3.1 None — Baidu Baidu PC [Web Browser], Android None Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. v6.1.0 Baidu Movie Baidu Movie 2000 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #08. BBBroadcast BBBroadcast 1.2 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #12. Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide 1-1 Chapter 1 P2P Protocols Introduction Table 1-1 P2P Protocols (continued) Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments BitTorrent BitTorrent v4.0.1 6881-6889, 6969 Supported Bittorrent Sync as of PP#38 Android v-1.1.37, iOS v-1.1.118 ans PC exeem v0.23 v-1.1.27. -

Peer to Peer Resources

Peer To Peer Resources By Marcus P. Zillman, M.S., A.M.H.A. Executive Director – Virtual Private Library [email protected] This January 2009 column Peer To Peer Resources is a comprehensive list of peer to peer resources, sources and sites available over the Internet and the World Wide Web including peer to peer, file sharing, and grid and matrix search engines. The below list is taken from the peer to peer research section of my Subject Tracer™ Information Blog titled Deep Web Research and is constantly updated with Subject Tracer™ bots at the following URL: http://www.DeepWebResearch.info/ These resources and sources will help you to discover the many pathways available to you through the Internet for obtaining and locating peer to peer sources in todays rapidly changing data procurement society. This is a MUST information keeper for those seeking the latest and greatest peer to peer resources! Peer To Peer Resources: ALPINE Network - SourceForge: Project http://sourceforge.net/projects/alpine/ An Efficient Scheme for Query Processing on Peer-to-Peer Networks http://aeolusres.homestead.com/files/index.html angrycoffee.com http://www.AngryCoffee.com/ Azureus - Vuze Java Bittorrent Client http://azureus.sourceforge.net/ 1 January 2009 Zillman Column – Peer To Peer Resources http://www.zillmancolumns.com/ [email protected] © 2009 Marcus P. Zillman, M.S., A.M.H.A. BadBlue http://badblue.com/ Between Rhizomes and Trees: P2P Information Systems by Bryn Loban http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1182 -

Internet Contract

Diocese of Youngstown Office of Catholic Schools Our Lady of Peace Revised 2005 Student use of the INTERNET Educational Acceptable Use Policy and Agreement Student use of the Internet on school computer hardware, on school premises, or through school obtained accounts, both on-site and through remote connections, is governed in accordance with Diocesan Policy, the policies of the Administrators’ Handbook and the Student/ Family Handbook. The MISSION of OLOP school Technology Committee, working in partnership with faculty, students and administrators, is to research and deploy common everyday technology into the infrastructure in such a way as to benefit the students and staff not by teaching technology, but teaching how to utilize existing technologies to gain a richer learning experience and understanding of how to most effectively utilize the technology that is now so common place in our everyday lives. Please read the following carefully before signing the attached agreement. INTRODUCTION: The Our Lady Of Peace School (OLOP) offers world wide web Internet access to your child at his/her school. OLOP provides computer equipment, computer services, and Internet access to its students and staff for educational purposes only, offering vast, diverse, and unique resources to promote educational excellence at OLOP School. The purpose of this document is to inform parents, guardians and students and all users of the availability of the Internet resources, as well as the rules governing its use, and to obtain express parental or guardian permission for an individual student to use technology and the Internet while at school. The computer system and all computer software and hardware is the property of the school. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

The Copyright Crusade

The Copyright Crusade Abstract During the winter and spring of 2001, the author, chief technology officer in Viant's media and entertainment practice, led an extensive inqUiry to assess the potential impact of extant Internet file-sharing capabilities on the business models of copyright owners and holders. During the course of this project he and his associates explored the tensions that exist or may soon exist among peer-to-peer start-ups, "pirates" and "hackers," intellectual property companies, established media channels, and unwitting consumers caught in the middle. This research report gives the context for the battleground that has emerged, and calls upon the players to consider new, productive solutions and business models that support profitable, legal access to intellectual property via digital media. by Andrew C Frank. eTO [email protected] Viant Media and Entertainment Reinhold Bel/tIer [email protected] Aaron Markham [email protected] assisted by Bmre Forest ~ VI ANT 1 Call to Arms Well before the Internet. it was known that PCs connected to two-way public networks posed a problem for copyright holders. The problem first came to light when the Software Publishers Association (now the Software & Information Industry Association), with the backing of Microsoft and others, took on computer Bulletin Board System (BBS) operators in the late 1980s for facilitating trade in copyrighted computer software, making examples of "sysops" (as system operators were then known) by assisting the FBI in orchestrat ing raids on their homes. and taking similar legal action against institutional piracy in high profile U.S. businesses and universities.' At the same time. -

Instructions for Using Your PC ǍʻĒˊ Ƽ͔ūś

Instructions for using your PC ǍʻĒˊ ƽ͔ūś Be careful with computer viruses !!! Be careful of sending ᡅĽ/ͼ͛ᩥਜ਼ƶ҉ɦϹ࿕ZPǎ Ǖễƅ͟¦ᰈ Make sure to install anti-virus software in your PC personal profile and ᡅƽញƼɦḳâ 5☦ՈǍʻPǎᡅ !!! information !!! It is very dangerous !!! ΚTẝ«ŵ┭ՈT Stop violation of copyright concerning illegal acts of ơųጛňƿՈ☢ͩ ⚷<ǕOᜐ&« transmitting music and ₑᡅՈϔǒ]ᡅ others through the Don’t forget to backup ඡȭ]dzÑՈ Internet !!! important data !!! Ȥᩴ̣é If another person looks in at your E-mail, it’s a big ὲâΞȘᝯɣr problem !!! Don’t install software in dz]ǣrPǎᡅ ]ᡅîPéḳâ╓ ͛ƽញ4̶ᾬϹ࿕ ۅTake care of keeping your some other PCs without ˊΙǺ password !!! permission !!! ₐ Stop sending the followings !!! ŌՈϹوInformation against public order and Somebody targets on your PC for Pǎ]ᡅǕễạǑ͘͝ࢭÛ ΞȘƅ¦Ƿń morals illegal access !!! Ոƅ͟ǻᢊ᫁ĐՈ ࿕Ϭ⓶̗ʵ£࿁îƷljĈ Information about discrimination, Shut out those attacks with firewall untruth and bad reputation against a !!! Ǎʻ ᰻ǡT person ᤘἌ᭔ ᆘჍഀ ጠᅼૐᾑ ᭼᭨᭞ᮞęɪᬡᬡǰɟ ᆘȐೈ ᾑ ጠᅼ3ظ ᤘἌ᭔ ǰɟᯓۀ᭞ᮞᮐᮧ᭪᭑ᮖ᭤ᬞᬢ ഄᅤ Έʡȩîᬡ͒ͮᬢـ ᅼܘᆘȐೈ ǸᆜሹظᤘἌ᭔ ཬᴔ ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᬞᬢŽᬍ᭑ᮖ᭤̛ɏ᭨ᮀ᭳ᭅ ரἨ᳜ᄌ࿘Π ؼ˨ഀ ୈὼ$ ഄጵ↬3L ʍ୰ᬞᯓ ᄨῼ33 Ȋථᬚᬌᬻᯓ ഄ˽ ઁǢᬝຨϙଙͮـᅰჴڹެ ሤᆵͨ˜Ɍ ጵႸᾀ żᆘ᭔ ᬝᬜΪ̎UઁɃᬢ ࡶ୰ᬝ᭲ᮧ᭪ᬢ ᄨؼᾭᄨ ᾑ ٕᅨ ΰ̛ᬞ᭫ᮌᯓ ᭻᭮᭚᭮ᮂᭅ ሬČ ཬȴ3 ᾘɤɟ3 Ƌᬿᬍᬞᯓ ᬿᬒᬼۏąഄᅼ Ѹᆠᅨ ᮌᮧᮖᭅ ᛴܠ ఼ ᆬð3 ᤘἌ᭔ ƂŬᯓ ᭨ᮀ᭳᭑᭒ᭅƖ̳ᬞ ĩᬡ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᬞٴ ரἨ᳜ᄌ࿘ ᭼᭤ᮚᮧ᭴ᬡɼǂᬢ ڹެ ᵌೈჰ˨ ˜ϐ ᛄሤ↬3 ᆜೈᯌ ϤᏤ ᬊᬖᬽᬊᬻᯓ ᮞ᭤᭳ᮧᮖᬊᬝᬚ ሬČʀ ͌ǜ ąഄᅼ ΰ̛ᬞ ޅᬝᬒᬡ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᭅ ᤘἌ᭔Π ͬϐʼ ᆬð3 ʏͦᬞɃᬌᬾȩî ēᬖᬙᬾᯓ ܘˑˑᏬୀΠ ᄨؼὼ ሹ ߍɋᬞᬒᬾȩî ᮀᭌ᭑᭔ᮧᮖwƫᬚފᴰᆘ࿘ჸ $±ᅠʀ =Ė ܘČٍᅨ ᙌۨ5ࡨٍὼ ሹ ഄϤᏤ ᤘἌ᭔ ኩ˰Π3 ᬢ͒ͮᬊᬝᯓ ᭢ᮎ᭮᭳᭑᭳ᬊᬻᯓـ ʧʧ¥¥ᬚᬚP2PP2P᭨᭨ᮀᮀ᭳᭳᭑᭑᭒᭒ᬢᬢ DODO NOTNOT useuse P2PP2P softwaresoftware ̦̦ɪɪᬚᬚᬀᬀᬱᬱᬎᬎᭆᭆᯓᯓ inin campuscampus networknetwork !!!! Z ʧ¥᭸᭮᭳ᮚᮧ᭚ᬞᬄᬾͮᬢȴƏΜˉ᭢᭤᭱ Z All communications in our campus network are ᬈᬿᬙᬱᬌʧ¥ᬚP2P᭨ᮀ always monitored automatically. -

Strategic Intertextuality in Three of John Lennonâ•Žs Late Beatles Songs

STRATEGIC INTERTEXTUALITY IN THREE OF JOHN LENNON’S LATE BEATLES SONGS* MARK SPICER his article will focus on an aspect of the Beatles’ compositional practice that I believe T merits further attention, one that helps to define their late style (that is, from the ground- breaking album Revolver [1966] onwards) and which has had a profound influence on all subsequent composers of popular music: namely, their method of drawing on the resources of pre-existing music (or lyrics, or both) when writing and recording new songs. This may at first seem entirely obvious, especially since nowadays such a practice has been adopted routinely by many songwriters and producers, and is in fact the prevailing compositional strategy within certain pop and rock genres, rap being probably the most blatant example. Many rap artists are well known for their so-called “rap versions,” as Tim Hughes has described them, in which a distinctive element of a pre-existing song is lifted out of its original context—typically via digital sampling—and used as the foundation upon which a new song is built.1 Will Smith’s hit “Wild Wild West” (1999), for example, is composed around a sample of the bass-driven main groove from Stevie Wonder’s funk classic “I Wish” (1976); and Eminem’s hit “Like Toy Soldiers” * This essay is based in part on the first chapter of my dissertation, “British Pop-Rock Music in the Post-Beatles Era” (Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, 2001). An earlier version was presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory, Columbus, in November 2002.