A Report from the Cambridge Primary Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebook » Celine Dion -- Taking Chances: Piano/Vocal/Chords ~ Read

Celine Dion -- Taking Chances: Piano/Vocal/Chords < Book « 9IEWNNO5MT Celine Dion -- Taking Ch ances: Piano/V ocal/Ch ords By Celine Dion Alfred Publishing Co Inc.,U.S., United States, 2008. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 297 x 224 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book. Winner of 5 Grammy Awards, 10 World Music Awards, 7 American Music Awards, and 21 Juno Awards, French superstar Celine Dion is back with her latest album, Taking Chances. Best-known for the No. 1 single, Taking Chances, the album was released internationally to critical acclaim. To celebrate, Celine kicks off her Taking Chances Tour in February of 2008. Alfred introduces the album-matching folio to Celine Dion s Taking Chances. Music includes lyrics, melody line, and chord changes with professionally arranged piano accompaniment. Titles: Taking Chances * Alone * Eyes on Me * My Love * Shadow of Love * Surprise Surprise * This Time * New Dawn * A Song for You * A World to Believe In * Can t Fight the Feelin * I Got Nothin Left * Right Next to the Right One * Fade Away * That s Just the Woman in Me * Skies of L.A. READ ONLINE [ 5.2 MB ] Reviews The book is straightforward in read safer to recognize. This really is for anyone who statte there had not been a worthy of looking at. You may like just how the blogger create this publication. -- Friedrich Nolan It is straightforward in read through preferable to fully grasp. It is really simplistic but excitement in the 50 percent of the pdf. Your life span will be enhance once you comprehensive looking at this pdf. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Some Thoughts on Reading Harry Potter in Latin

26-35_a_firmage_harry potter.qxp 1/8/2007 2:49 PM Page 26 SUNSTONE The moment America yields to its neurotic impulse to become a Christian nation, instead of being a nation that respects and values Christianity, Harry Potter and the rest of our imaginative life will join Darwin on the scaffold erected each year by the Kansas City school board to toast great ideas. THREE CHEERS FOR CICERO SOME THOUGHTS ON READING HARRY POTTER IN LATIN By Edwin Firmage Jr. AST CHRISTMAS, I DECIDED TO Dominus et Domina Dursley, qui vivebant in brush up on my Latin. I say brush aedibus Gestationis Ligustrorum numero quat- L up, but vigorous scrubbing with tuor signatis. By the end of the first page, I steel wool designed to remove heavy rust was hooked. I finished the book two weeks would be more accurate. As an undergrad- later. Following are some reflections on uate, I studied Latin, as well as a number of reading a twentieth-century children’s classic other dead languages, but had not done done into the language of Cicero, two thou- much with it in the almost twenty-five years sand years dead. since. After a couple of weeks’ review with a well-thumbed copy of Wheelock, I was HAT INITIALLY SURPRISED ready to begin my first big Latin read in me most is the fact that the decades. Providentially, at that very mo- W book could be done into Latin. ment, my kids were cleaning out their rats’ It’s a testament to the timeless quality of J. nest of a bookcase and came across a copy K. -

Lancaster, PA March 14, 2013 – March 17, 2013

222000111333 RRReeegggiiiooonnnaaalll RRReeesssuuullltttsss Lancaster, PA March 14, 2013 – March 17, 2013 Petite Mr. StarQuest Christopher Soares - Oh Susannah - Creative Dance Center Mr. StarQuest Jeremy Lowery - I Won't Give Up - Premier Dance Center Petite Miss StarQuest Caroline Frey - I'm A Star - Creative Dance Center Junior Miss StarQuest Cadean Rogers - Raise The Roof - Creative Dance Center Teen Miss StarQuest Lauren Stevens - A Little Faith - Creative Dance Center Miss StarQuest Tiffani Wills - Without You - Creative Dance Center Top Select Petite Solo 1st Place - Reese Brown - Grave - Creative Dance Center 2nd Place - Elizabeth Doane - Over The Rainbow - Creative Dance Center 3rd Place - Laila Gilliam - Working Day And Night - Miss Heathers School Of Dance Top Select Junior Solo 1st Place - Casey Beetle - Lost - Creative Dance Center 2nd Place - Brandon Ranalli - The Face - Broadway Bound Dance Academy 3rd Place - Cadean Rogers - Heaven - Creative Dance Center 4th Place - Ellie Mundie - Rivergod - Creative Dance Center 5th Place - Julia Adams - The Witch is Dead - The Dance Academy 6th Place - Madison Bender - Born This Way - Miss Jeannes School of Dance Arts 7th Place - Trevor Yost - Sante Fe - Miss Tanyas Expression of Dance 8th Place - Jessica Decembrino - Starstruck - On Edge Movement 9th Place - Mackenzie Butler - Cover Girl - Broadway Bound Dance Academy 10th Place - Emily Cohn - Safe And Sound - Creative Dance Center Top Select Teen Solo 1st Place - Lauren Stevens - A Little Faith - Creative Dance Center 2nd Place - -

2020 Term 2 Week 2 Newsletter

ST PATRICK’S GUILDFORD Principal: Steven Jones Parish Contact Details 34 Calliope Street Parish Priest: Fr Peter Blayney, Guildford 2161 Parish Associate: Sister Helen Cunningham OP Phone: 8728 7300 Phone: 9632 2672 Email: [email protected] www.stpatsguildford.catholic.edu.au Newsletter 1 Thursday, 7th May 2020 PRINCIPAL’S MESSAGE Dear Parents, As we come towards the end of the second week of Term 2, we are excited as a school community to commence the gradual transitioning back of our students from next Monday 11 May. We understand that some families and students will be very excited, whilst others may be a little hesitant and even quite nervous. These are all natural feelings during this time of unprecedented times. By slowly transitioning our students back, staff can support each and every child to feel once again comfortable and that school is just as it was before they left. The feedback was extremely positive and helpful in providing further ways to support our school community. It is important that parents please take time to read important information within this newsletter to assist in the safe transition commencing next week. Thank you to the parents who attended the two Zoom meetings yesterday. “God gave mothers special gifts, He made them unique. But one thing that all mothers love, Are Kisses on the cheek.” This Sunday we have the opportunity to display in words and actions our appreciation and thanks to all the mothers in our lives. Unfortunately for children, mothers and grandparents this year there has not been the opportunities as a school community to celebrate Mother’s Day (Mothers’ Day stall, Mothers’ Day Mass, Mothers’ Day morning tea). -

Find Ebook \\ Celine Dion -- Taking Chances: Piano/Vocal/Chords

UVR4W5GSMSRZ PDF < Celine Dion -- Taking Chances: Piano/Vocal/Chords Celine Dion -- Taking Chances: Piano/Vocal/Chords Filesize: 3.43 MB Reviews The ebook is fantastic and great. I really could comprehended every thing out of this published e publication. You can expect to like the way the blogger write this publication. (Precious Farrell) DISCLAIMER | DMCA YKE4J4JT3QYH \ Doc \ Celine Dion -- Taking Chances: Piano/Vocal/Chords CELINE DION -- TAKING CHANCES: PIANO/VOCAL/CHORDS Alfred Publishing Co Inc.,U.S., United States, 2008. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 297 x 224 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book. Winner of 5 Grammy Awards, 10 World Music Awards, 7 American Music Awards, and 21 Juno Awards, French superstar Celine Dion is back with her latest album, Taking Chances. Best-known for the No. 1 single, Taking Chances, the album was released internationally to critical acclaim. To celebrate, Celine kicks o her Taking Chances Tour in February of 2008. Alfred introduces the album-matching folio to Celine Dion s Taking Chances. Music includes lyrics, melody line, and chord changes with professionally arranged piano accompaniment. Titles: Taking Chances * Alone * Eyes on Me * My Love * Shadow of Love * Surprise Surprise * This Time * New Dawn * A Song for You * A World to Believe In * Can t Fight the Feelin * I Got Nothin Left * Right Next to the Right One * Fade Away * That s Just the Woman in Me * Skies of L.A. Read Celine Dion -- Taking Chances: Piano/Vocal/Chords Online Download PDF Celine Dion -- Taking Chances: Piano/Vocal/Chords 6OWYK0NOVF6O // Book < Celine Dion -- Taking Chances: Piano/Vocal/Chords Relevant Kindle Books The genuine book marketing case analysis of the the lam light. -

Celine Dion My Love Ultimate Essential Collection 2CD 2008 Losslessrar

1 / 2 Celine Dion My Love Ultimate Essential Collection (2CD) (2008) [lossless].rar Where Does My. Heart Beat Now 2.. Celine Dion My Love: Ultimate Essential Collection (2CD) (2008) [lossless].rar, panduan belajar corel draw x3 john w .... Cpasbien. pe] Celine Dion - Celine Une seule fois Live 2013 (2014) [320] ... ABBA - GOLD_Complete Edition 2CD (2008 Japan Edition)⭐MP3 ... ABBA - The Essential Collection (2 CD) (2012)[FLAC] ... Aloe Blacc - All Love Everything (2020) Mp3 320kbps [PMEDIA] ⭐️ ... Driving In My Car-Ultimate Car Anthems (2019) .... The Ultimate Love Songs Collection, Volume 4/ 20-Apr-2014 16:20 - [DIR] ... The Very Best of Euphoric Dance Breakdown: Summer 2008/ 20-Apr-2014 16:20 - [DIR] ... With a Little Help From My Fans - The Beatles Revisités 1969-2005/ ... Silver Bells: The Essential Country Christmas Album/ 20-Apr-2014 16:20 - [DIR] .... Jun 14, 2020 — Celine Dion My Love: Ultimate Essential Collection (2CD) (2008) [lossless].rar · Dil Hai Tumhaara 3 720p download movie · download novel .... Mar 22, 2021 — Celine Dion My Love: Ultimate Essential Collection (2CD) (2008) [lossless].rar. It is, in fact, a new category: the ultra widebody business jet.. Mar 6, 2018 — ... how,to,install,nx,8.5,crack,windows,7,.,hng,dn,vn,hnh,my,cnc,v,cc,phn ... ,via,torrent,.,password,mediafire,Unigraphics,Nx,8,5,32,Bit,download .... Man.2008. ... XViD-WBZ BBC 2CD Ballroom Dance Bryan Smith, Andy Ross Orchestras ... capture it for bb Web Template Monster Flash Templates Collection (109).rar ... X264-AMIABLE no love eminem download link Libera. ... to Blow Her Mind in Bed The essential guide for any man who wants to satisfy his woman The. -

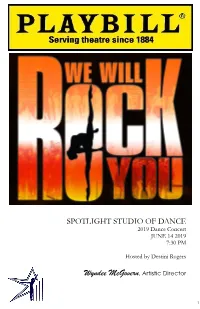

Wyndee Mcgovern, Artistic Director

SPOTLIGHT STUDIO OF DANCE 2019 Dance Concert JUNE 14 2019 7:30 PM Hosted by Destini Rogers Wyndee McGovern, Artistic Director 1 2 Thank you to the following Teachers & Choreographers for their time and commitment to providing quality dance ed- ucation & training: ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Wyndee McGovern TEACHING STAFF Jennifer Boothe Sara Cato Brent Curtis Cyra Duncan Cameron Gregg Allyson Kelly Renee Lopez Christine Puhalla Somaya Reda Kaitie Richmond Jennifer Shead Kya Smith Lisa Swenton Lenaya Williams GUEST CHOREOGRAPHERS & TEACHERS Will Bell Duncan Cooper Scott Fowler MJ Jackson Robbie Nicholson Destini Rogers Rasta Thomas Brandee Stuart Donna Vaughn 3 “The dance is over, the applause subsided, but the joy and feeling will stay with you forever.” CLASS OF 2019 OUR GRADUATES! MESHA HESTER GABRIELLE FERGUSON 4 McGovern Method Certified 5 “WE WILL ROCK YOU” Act I Choreographer ACT I - Performance Order “WE WILL ROCK YOU” Overture Wyndee McGovern Lance Kasten “Bennie and the Jets” Senior Jazz Group Wyndee McGovern/ Sarina Donze, Gabrielle Ferguson, Mesha Hester, Alexa Kasten, Destini Rogers Sydney Kuhn, Grace Mickel, Jenna Milan, Emme Mowrey, Abagale Neuberger, Ashley Reed, Zoe Schley, Kya Smith “I love Betsy” Mini Musical Theater Solo Renee Lopez Sam Klotz - Mini Mr. Showbiz “What a Wonderful World” Junior Lyrical Group Jenn Shead Ellis Byrd, Corynn Coleman, Zyeeda Farooq, Maggie Fritz, Alexys Giunta, Madison Hughes, Mackenzi McGovern, Arianna Schriner, Lilly Schultz, Aubrey Taylor “Have Mercy” Teen Contemporary Group Somaya Reda Trinity Aldridge, -

What Difference Does It Make?' - the Gospel in Contemporary Culture

What Difference Does it Make?' - The Gospel in Contemporary Culture Wednesday 20 February 2008 Lecture held in Great St Mary's Church, Cambridge, as part of the "A World to Believe in - Cambridge Consultations on Faith, Humanity and the Future" Sessions Archbishop at Great St Mary's Church I want to begin with a mention of one of the great classics of Cambridge literature. Some of you will I hope have read Gwen Raverat's book, Period Piece: a Cambridge childhood (those who haven't have a pleasure ahead of them). In it she gives a picture of her family, an Edwardian, academic family, the Darwins in fact. And among her uncles and aunts are several figures of ripe eccentricity. One uncle was absolutely convinced that whenever he left the room the furniture would rearrange itself while he was out. He was constantly trying to get back quickly enough to catch it in the act. Now, that is admittedly a rather extreme case of Cambridge eccentricity, but I suspect that it may ring one or two bells with some people around here. How many of us, I wonder, as children had that haunting suspicion that perhaps rooms rearranged themselves when we were out? Wondered whether what we were seeing was what still went on when our backs were turned? And I want to begin by thinking about that aspect of our human being in the world which is puzzled, frustrated, haunted by the idea that maybe what we see isn't the whole story, and maybe our individual perception is not the measure of all truth. -

2015 New Orleans Regionals

2015 NEW ORLEANS REGIONALS THE IN10SITY CHALLENGE Studio Average Top Non-Solo 1st Place- $1,000 Dance Factory 278.1 “Wilkomenn” 2nd Place- $750 To The Pointe Academy of Dance 270.8 “The River” 3rd Place- $500 The Dance Pointe 269.46 “Powerless” 4th Place- $250 Elite Dance Force 265.18 “No Other Man” 5th Place- $100 Phyllis Guy Dance Center 264.02 “How Heavy Are These Words” In10se Routines Routine Score Studio Prize In10se Mini Secret 271.7 To The Pointe Academy of Dance $160 In10se Junior Wilkomenn 280.5 Dance Factory $480 In10se Teen With You- Marcel Cavaliere 281.7 Dance Factory $90 In10se Senior Now Comes the Night- Vernon Brooks 277.9 Dance Factory $90 DIVISIONAL OVERALLS ELITE MINI SOLO 1st Blow The System- Chloe Barbera To The Pointe Academy of Dance 2nd SuperStar- Ali Guidroz The Dance Pointe 3rd Broadway Banana- Cara Lemoine The Dance Pointe PREMIER MINI SOLO 1st Lullaby- Victoria Sharp Phyllis Guy Dance Center 2nd SuperSonic- Marley Broussard The Dance Pointe 3rd Swinging On a Star- Molly Kate Skupien Phyllis Guy Dance Center 4th I Enjoy Being a Gril- Saydee Heil Phyllis Guy Dance Center 5th Amazing Mazie- Analise Armand Phyllis Guy Dance Center DEBUT MINI SOLO 1st Lullaby of Broadway- Kennen Santos Dance Factory ELITE MINI DUET/TRIO 1st Funky Monkey The Dance Pointe PREMIER MINI DUET/TRIO 1st The Prayer Phyllis Guy Dance Center 2nd Boom Phyllis Guy Dance Center 3rd Miracle Southern Sass Dance Company DEBUT MINI DUET/TRIO 1st Tell My Mama Elite Dance Force ELITE MINI SMALL GROUP 1st Secret To The Pointe Academy of Dance PREMIER -

2021 Colmbus Results.Docx

Columbus, OH March 10- 14th, 2021 Elite 8 Petite Dancer Kinley Barnes - Like That - Haja Dance Company 1st Runner-Up - Alaina Harris - Don't Stop - Haja Dance Company Elite 8 Junior Dancer Kendalynn Roberts - Ashes - Haja Dance Company 1st Runner-Up - Mia Astacio - Elastic Heart - NorthPointe Dance Academy 2nd Runner-Up - Alyssa Nelson - Hit Me With A Hot Note - Platinum Dance Company Elite 8 Teen Dancer Emmie Dalton - The Lucky Ones - Haja Dance Company 1st Runner-Up - Brianna Hicks - I Am Changing - Haja Dance Company 2nd Runner-Up - Aubrey Lampman - You Are The Reason - Platinum Dance Company Elite 8 Senior Dancer Ashley Smith - The First Time - Haja Dance Company 1st Runner-Up - Jessica Babich - Ubiquitous - Haja Dance Company 2nd Runner-Up - Samantha Grana - Via Dolorosa - Haja Dance Company Top Select Petite Solo 1 - Lyric Mitchell - Mr. Bassman - Dance Connection Inc. 2 - Rylan Reynolds - Hallelujah - NorthPointe Dance Academy 3 - Alexa Hoyt - Friend Like Me - NorthPointe Dance Academy 4 - Kinley Barnes - Like That - Haja Dance Company 5 - Alaina Harris - Don't Stop - Haja Dance Company Top Select Junior Solo 1 - Madeleine Shen - The Bridge - NorthPointe Dance Academy 2 - Samantha Voice - Dream On - NorthPointe Dance Academy 3 - Julia Hoffman - Party Girl - Sophistication Dance Company 4 - Gemma Reep - Poison - NorthPointe Dance Academy 5 - Kendalynn Roberts - Ashes - Haja Dance Company 6 - Makaylyn Lewis - Run To You - NorthPointe Dance Academy 7 - Maggie Ray - Brown Eyed Girl - Dance Connection Inc. 8 - Julianna Harris - The Mask - Haja Dance Company 9 - Brooklyn Glenn - Saturn - Haja Dance Company 10 - Madelyn Bobby - Listen - Haja Dance Company 11 - Alyssa Nelson - Hit Me With A Hot Note - Platinum Dance Company 12 - Addie Landon - Kaboom Pow - Dance Connection Inc. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 23/02/2020 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 23/02/2020 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born My Way - Frank Sinatra Jolene - Dolly Parton Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Let It Go - Idina Menzel Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Dancing Queen - ABBA Santeria - Sublime Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Fly Me to the Moon - Frank Sinatra Turn The Page - Bob Seger Don't Stop Believing - Journey Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Valerie - Amy Winehouse Your Man - Josh Turner Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Old Town Road (remix) - Lil Nas X EXPLICIT House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Creep - Radiohead EXPLICIT Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wannabe - Spice Girls Dance Monkey - Tones and I My Girl - The Temptations Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Black Velvet - Alannah Myles All Of Me - John Legend Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Perfect - Ed Sheeran These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash I Wanna Dance with Somebody - Whitney Houston Beautiful Crazy - Luke Combs Truth Hurts - Lizzo EXPLICIT Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Your Song - Elton John Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Zombie - The Cranberries Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Jackson - Johnny Cash I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Girl Crush - Little Big Town Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Crazy - Patsy Cline Dreams