The Arrangements of Nelson Riddle for Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazz Lines Publications Fall Catalog 2009

Jazz lines PubLications faLL CataLog 2009 Vocal and Instrumental Big Band and Small Group Arrangements from Original Manuscripts & Accurate Transcriptions Jazz Lines Publications PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA www.ejazzlines.com [email protected] 518-587-1102 518-587-2325 (Fax) KEY: I=Instrumental; FV=Female Vocal; MV=Male Vocal; FVQ=Female Vocal Quartet; FVT= Femal Vocal Trio PERFORMER / TITLE CAT # DESCRIPTION STYLE PRICE FORMAT ARRANGER Here is the extended version of I've Got a Gal in Kalamazoo, made famous by the Glenn Miller Orchestra in the film Orchestra Wives. This chart differs significantly from the studio recorded version, and has a full chorus band intro, an interlude leading to the vocals, an extra band bridge into a vocal reprise, plus an added 24 bar band section to close. At five and a half minutes long, it's a (I'VE GOT A GAL IN) VOCAL / SWING - LL-2100 showstopper. The arrangement is scored for male vocalist plus a backing group of 5 - ideally girl, 3 tenors and baritone, and in the GLENN MILLER $ 65.00 MV/FVQ DIFF KALAMAZOO Saxes Alto 2 and Tenor 1 both double Clarinets. The Tenor solo is written on the 2nd Tenor part and also cross-cued on the male vocal part. The vocal whistling in the interlude is cued on the piano part, and we have written out the opening Trumpet solo in full. Trumpets 1-4: Eb6, Bb5, Bb5, Bb5; Trombones 1-4: Bb4, Ab4, Ab4, F4; Male Vocal: Db3 - Db4 (8 steps): Vocal key: Db to Gb. -

The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents

THE CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA WHAT IS AN ORCHESTRA? Student Learning Lab for The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family ...................... 3 PART 2: Let’s Listen to Nagoya Marimbas ...................... 6 PART 3: Music Learning Lab ................................................ 8 2 PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family An orchestra consists of musicians organized by instrument “family” groups. The four instrument families are: strings, woodwinds, brass and percussion. Today we are going to explore the percussion family. Get your tapping fingers and toes ready! The percussion family includes all of the instruments that are “struck” in some way. We have no official records of when humans first used percussion instruments, but from ancient times, drums have been used for tribal dances and for communications of all kinds. Today, there are more instruments in the percussion family than in any other. They can be grouped into two types: 1. Percussion instruments that make just one pitch. These include: Snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, wood block, gong, maracas and castanets Triangle Castanets Tambourine Snare Drum Wood Block Gong Maracas Bass Drum Cymbals 3 2. Percussion instruments that play different pitches, even a melody. These include: Kettle drums (also called timpani), the xylophone (and marimba), orchestra bells, the celesta and the piano Piano Celesta Orchestra Bells Xylophone Kettle Drum How percussion instruments work There are several ways to get a percussion instrument to make a sound. You can strike some percussion instruments with a stick or mallet (snare drum, bass drum, kettle drum, triangle, xylophone); or with your hand (tambourine). -

Amjad Ali Khan & Sharon Isbin

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

Im Auftrag: Medienagentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 01805 - 060347 90476 [email protected]

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 01805 - 060347 90476 [email protected] FRANK SINATRAS ZEITLOSE MUSIK WIRD WELTWEIT MIT DER KOMPLETTEN KARRIERE UMFASSENDEN JAHRHUNDERTCOLLECTION ‘ULTIMATE SINATRA’ GEFEIERT ‘Ultimate Sinatra’ erscheint als CD, Download, 2LP & limited 4CD/Digital Deluxe Editions und vereint zum ersten Mal die wichtigsten Aufnahmen aus seiner Zeit bei Columbia, Capitol und Reprise! “Ich liebe es, Musik zu machen. Es gibt kaum etwas, womit ich meine Zeit lieber verbringen würde.” – Frank Sinatra Dieses Jahr, am 12. Dezember, wäre Frank Sinatra 100 Jahre alt geworden. Anlässlich dieses Jubiläums hat Capitol/Universal Music eine neue, die komplette Karriere des legendären Entertainers umspannende Collection seiner zeitlosen Musik zusammengestellt. Ultimate Sinatra ist als 25 Track- CD, 26 Track-Download, 24 Track-180g Vinyl Doppel-LP und als limitierte 101 Track Deluxe 4CD- und Download-Version erhältlich und vereint erstmals die wichtigsten Columbia-, Capitol- und Reprise- Aufnahmen in einem Paket. Alle Formate enthalten bisher unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen von Sinatra und die 4CD-Deluxe, bzw. 2LP-Vinyl Versionen enthalten zusätzlich Download-Codes für weitere Bonustracks. Frank Sinatra ist die Stimme des 20. Jahrhunderts und seine Studiokarriere dauerte unglaubliche sechs Jahrzehnte: 1939 sang er seinen ersten Song ein und seine letzten Aufnahmen machte er im Jahr 1993 für sein weltweit gefeiertes, mehrfach mit Platin ausgezeichnetes Album Duets and Duets II. Alle Versionen von Ultimate Sinatra beginnen mit “All Or Nothing At All”, aufgenommen mit Harry James and his Orchestra am 31. August 1939 bei Sinatras erster Studiosession. Es war die erste von fast 100 Bigband-Aufnahmen mit den Harry James und Tommy Dorsey Orchestern. -

MUNI 20151109 – Evergreeny 06 (Thomas „Fats“ Waller, Victor Young)

MUNI 20151109 – Evergreeny 06 (Thomas „Fats“ Waller, Victor Young) Honeysuckle Rose – dokončení z minulé přednášky Lena Horne 2:51 First published 1957. Nat Brandwynne Orchestra, conducted by Lennie Hayton. SP RCA 45-1120. CD Recall 305. Velma Middleton-Louis Armstrong 2:56 New York, April 26, 1955. Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars. LP Columbia CL 708. CD Columbia 64927 Ella Fitzgerald 2:20 Savoy Ballroom, New York, December 10, 1937. Chick Webb Orchestra. CD Musica MJCD 1110. Ella Fitzgerald 1:42> July 15, 1963 New York. Count Basie and His Orchestra. LP Verve V6-4061. CD Verve 539 059-2. Sarah Vaughan 2:22 Mister Kelly‟s, Chicago, August 6, 1957. Jimmy Jones Trio. LP Mercury MG 20326. CD EmArcy 832 791-2. Nat King Cole Trio – instrumental 2:32 December 6, 1940 Los Angeles. Nat Cole-piano, Oscar Moore-g, Wesley Prince-b. 78 rpm Decca 8535. CD GRP 16622. Jamey Aebersold 1:00> piano-bass-drums accompaniment. Doc Severinsen 3:43 1991, Bill Holman-arr. CD Amherst 94405. Broadway-Ain‟t Misbehavin‟ Broadway show. Ken Page, Nell Carter-voc. 2:30> 1978. LP RCA BL 02965. Sweet Sue, Just You (lyrics by Will J. Harris) - 1928 Fats Waller and His Rhythm: Herman Autrey-tp; Rudy Powell-cl, as; 2:55 Fats Waller-p,voc; James Smith-g; Charles Turner-b; Arnold Boling-dr. Camden, NJ, June 24, 1935. Victor 25087 / CD Gallerie GALE 412. Beautiful Love (Haven Gillespie, Wayne King, Egbert Van Alstyne) - 1931 Anita O’Day-voc; orchestra arranged and conducted by Buddy Bregman. 1:03> Los Angeles, December 6, 1955. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

J2P and P2J Ver 1

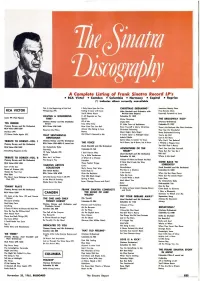

inulTo discography A Complete Listing of Frank Sinatra Record LP's RCA Victor Camden Columbia Harmony Capitol Reprise ( *) indicates album currently unavailable Is This the Beginning of the End I Only Have Eyes for You CHRISTMAS DREAMING* American Beauty Rose Whispering RCA VICTOR (PP) Falling in Love with Love (Alex Stordahl and Orchestra with Five Minutes More You'll Never Know the Kea Lane Singers) Farewell, Farewell to Love HAVING A WONDERFUL It All Depends on You Columbia CL 1032 (note: PP -Pied Pipers) TIME* Spasm' White Christmas THE BROADWAY KICK* (Tommy Dorsey and His Clambake All of Me Jingle Bells (Various Orchestras) YES INDEED Seven) Time After Time O' Little Town of Bethlehem Columbia CL 1297 (Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra) RCA Victor LPM 1643 How Cute Can You Be? Have Yourself a Merry Christmas There's No Business Like Show Business RCA Victor LPM 1229 Almost Like Being in Love Head on My Pillow Christmas Dreaming They Say It's Wonderful Stardust (PP) Nancy Silent Night, Holy Night Some Enchanted Evening I'll Never Smile Ohl What It Seemed to Me Again (PP) THAT SENTIMENTAL It Come Upon a Midnight Clear You're My Girl GENTLEMAN Adeste Fideles Lost in the Stars Santa Clous Is Conlin' to Town (Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra) Can't You Behave? TRIBUTE TO DORSEY -VOL. 1 Let It Snow, let It RCA Victor LPM THE VOICE Snow, Let It Snow I Whistle a Happy Tune (Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra) 6003 -2 record set (Axel Stordahl and His Orchestra) The Girl That I Marry RCA Victor LPM 1432 My Melancholy Baby ADVENTURES THE Can't You Just See Yourself Yearning Columbia CL 743 OF Everything Happens to Me HEART* There But For You Go I l'll Take Tallulah (PP) I Don't Know Why (Axel Stordahl and His Orchestra) Boli Ha'i Marie Try a Little Tenderness Columbia CL 953 Where Is My Bess? How Am Know TRIBUTE TO DORSEY -VOL. -

Pioneers of the Concept Album

Fancy Meeting You Here: Pioneers of the Concept Album Todd Decker Abstract: The introduction of the long-playing record in 1948 was the most aesthetically signi½cant tech- nological change in the century of the recorded music disc. The new format challenged record producers and recording artists of the 1950s to group sets of songs into marketable wholes and led to a ½rst generation of concept albums that predate more celebrated examples by rock bands from the 1960s. Two strategies used to unify concept albums in the 1950s stand out. The ½rst brought together performers unlikely to col- laborate in the world of live music making. The second strategy featured well-known singers in song- writer- or performer-centered albums of songs from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s recorded in contemporary musical styles. Recording artists discussed include Fred Astaire, Ella Fitzgerald, and Rosemary Clooney, among others. After setting the speed dial to 33 1/3, many Amer- icans christened their multiple-speed phonographs with the original cast album of Rodgers and Hammer - stein’s South Paci½c (1949) in the new long-playing record (lp) format. The South Paci½c cast album begins in dramatic fashion with the jagged leaps of the show tune “Bali Hai” arranged for the show’s large pit orchestra: suitable fanfare for the revolu- tion in popular music that followed the wide public adoption of the lp. Reportedly selling more than one million copies, the South Paci½c lp helped launch Columbia Records’ innovative new recorded music format, which, along with its longer playing TODD DECKER is an Associate time, also delivered better sound quality than the Professor of Musicology at Wash- 78s that had been the industry standard for the pre- ington University in St. -

Hedwig's Theme

Hedwig’s Theme SLS O L E ARN ING L AB Composer John Williams, best known for his movie soundtracks to films such as Star Wars and Harry Potter, has written some of the most iconic musical themes of our time. Let’s break this sentence down: • A composer is someone who writes music. • A soundtrack is music that accompanies a movie. • A musical theme is a small bit of recognizable music within a larger piece. Listen to your favorite pop song. It probably has a chorus, the recurring part that you love to sing along to. That’s kind of like a musical theme in “classical” music. Musical Themes in Hedwig’s Theme One of the most recognizable musical themes in cinematic history is Hedwig’s Theme, composed by John Williams for the movie Harry Potter and The Sorcerer’s Stone. The name suggests that the main musical theme represents Harry Potter’s owl, Hedwig. We first hear the theme played on the celesta before it is passed around to different instruments of the orchestra. A celesta, sometimes spelled celeste, looks like a miniature upright piano. When a key is pressed down, a hammer strikes a metal plate (a piano’s hammer strikes a string). You might think it sounds like a music box. Listen to the first theme from Hedwig’s Theme (0:00-0:40). Musical themes can represent different people, places, events, and even emotions. And composers aren’t limited to just one musical theme per piece. For Hedwig’s Theme, Williams composed three different musical themes. -

My Way: a Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra Has Audiences, Artists Singing “The Best Is Yet to Come”

Sinatra Tribute Lights Up The Phoenix Theatre Company’s Outdoor Stage My Way: A Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra has audiences, artists singing “The Best Is Yet To Come” (PHOENIX – March 18, 2021) The Phoenix Theatre Company concludes its series of socially- distanced outdoor shows with a swoon-worthy tribute to musical great Frank Sinatra. My Way: A Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra features the story and music of the first great popstar. The high-energy production runs at The Phoenix Theatre Company’s socially-distanced outdoor venue April 14 through May 23. My Way: A Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra is a walk down memory lane through the music of one of the greatest artists of all time. The production is set in a mid-century cabaret-style bar with an ensemble of four performers singing and dancing their way through vignettes of Sinatra’s life story. The Phoenix Theatre Company’s production includes modern touches in the costuming, an LED screen which serves as a backdrop and the high quality lighting and sound design audiences expect from The Phoenix Theatre Company. “Frank Sinatra was one of those rare performers who left audiences electrified,” says D. Scott Withers, director of My Way at The Phoenix Theatre Company. “His songs are timeless, tender and tough all at the same time. He drew people in with his approach to the lyrics and after the song ended, he left the air charged. He had a voltage.” The show includes Sinatra favorites and hidden gems performed by a three-piece orchestra and local Phoenix artists familiar to The Phoenix Theatre Company stage. -

Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy

e-misférica 5.2: Race and its Others (December 2008) www.hemisferica.org “You Make Me Feel So Young”: Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy by Eric Lott | University of Virginia In 1965, Frank Sinatra turned 50. In a Las Vegas engagement early the next year at the Sands Hotel, he made much of this fact, turning the entire performance—captured in the classic recording Sinatra at the Sands (1966)—into a meditation on aging, artistry, and maturity, punctuated by such key songs as “You Make Me Feel So Young,” “The September of My Years,” and “It Was a Very Good Year” (Sinatra 1966). Not only have few commentators noticed this, they also haven’t noticed that Sinatra’s way of negotiating the reality of age depended on a series of masks—blackface mostly, but also street Italianness and other guises. Though the Count Basie band backed him on these dates, Sinatra deployed Amos ‘n’ Andy shtick (lots of it) to vivify his persona; mocking Sammy Davis Jr. even as he adopted the speech patterns and vocal mannerisms of blacking up, he maneuvered around the threat of decrepitude and remasculinized himself in recognizably Rat-Pack ways. Sinatra’s Italian accents depended on an imagined blackness both mocked and ghosted in the exemplary performances of Sinatra at the Sands. Sinatra sings superbly all across the record, rooting his performance in an aura of affection and intimacy from his very first words (“How did all these people get in my room?”). “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Jilly’s West,” he says, playing with a persona (habitué of the famous 52nd Street New York bar Jilly’s Saloon) that by 1965 had nearly run its course. -

Tommy Dorsey 1 9

Glenn Miller Archives TOMMY DORSEY 1 9 3 7 Prepared by: DENNIS M. SPRAGG CHRONOLOGY Part 1 - Chapter 3 Updated February 10, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS January 1937 ................................................................................................................. 3 February 1937 .............................................................................................................. 22 March 1937 .................................................................................................................. 34 April 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 53 May 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 68 June 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 85 July 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 95 August 1937 ............................................................................................................... 111 September 1937 ......................................................................................................... 122 October 1937 ............................................................................................................. 138 November 1937 .........................................................................................................