Delta Podcast Transcript Introduction Paul Musgrave: Welcome To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friends of the Blue Hills |

Discover the Blue Hills Blue Hills Reservation Guide and Maps Friends of the Blue Hills PO Box 416 Milton, MA 02186 [email protected] Original edition produced by David Hodgdon and Thomas Palmer www.FriendsoftheBlueHills.org Friends of the Blue Hills 1 www.FriendsoftheBlueHills.org Introduction Whether you are a frequent sojourner in the Blue Hills, or a new glimpse of the unusual mating dance of the American woodcock. visitor, there is always something new to be explored in this inspiring You can spend your summers swimming at Houghton’s Pond, a landscape. Among the 7,000 plus acres there are opportunities to hike, kettle pond formation, gift of the glacial age, or pack your rod for some bike, ski, swim, climb and contemplate the simple beauty of nature. One fishing at Ponkapoag Pond. In the warmer months, try launching your can take a serpentine drive through the reservation, stopping to admire canoe on the Neponset River at Fowl Meadow. When the precipitation views along the way, or accept the challenge of hiking the Skyline Trail turns to snow, revisit Fowl Meadow for flat, easy cross-country skiing from beginning to end. or, alternatively, speed down the slopes at the Blue Hill Ski Area. For adventurous souls, there’s the challenge of biking Great Blue Hill or rock climbing on the vertical walls at Quincy Quarries in the northernmost part of the park. Those seeking a workout can hike the Skyline Trail from Quincy to Canton, a hike offering much elevation change and wonderful views. Even if you don’t consider yourself a serious hiker, you’ll still find easy rambles on trails that take you around Houghton’s Pond. -

Thesis-1998D-C289h.Pdf (10.80Mb)

AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF NATIVE AMERICAN HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS IN THE UNITED ST ATES by CARY MICHAEL CARNEY Bachelor of Arts University of Tulsa Tulsa, Oklahoma 1969 Master of Business Administration Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1992 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May, 1998 COPYRIGHT By Cary Michael Carney May, 1998 AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF NATIVE AMERICAN HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS IN THE UNITED STATES Thesis Approved Thesis Advisor oer;(H~ ii PREFACE Many phases of Native American education have been given extensive and adequate historical treatment. Works are plentiful on the boarding school program, the mission school efforts, and other select aspects of Native American education. Higher education for Indians, however, has received little attention. Select articles, passages, and occasional chapters touch on it, but usually only regarding selected topics or as an adjunct to education in general. There is no thorough and comprehensive history of Native American higher education in the United States. It is hoped this study will satisfy such a need, and prompt others to strive to advance knowledge and analysis in this area and to improve on what is presented here. The scope of this study is higher education for the Indian community, specifically within the continental United States, from the age of discovery to the present. Although, strictly speaking, the colonial period predates the United States, the society and culture of the nation as well as several of its more prominent universities stem from that period. -

Hyde Park Historical Record (Vol

' ' HYDE PARK ' ' HISTORICAL RECORD ^ ^ VOLUME IV : 1904 ^ ^ ISe HYDE PARK HISTORICAL SOCIETY j< * HYDE PARK, MASSACHUSETTS * * HYDE PARK HISTORICAL RECORD Volume IV— 1904 PUBLISHED BY THE HYDE PARK HISTORICAL SOCIETY HYDE PARK, MASS. PRESS OF . THE HYDE PARK GAZETTE . 1904 . OFFICERS FOR J904 President Charles G. Chick Recording Secretary Fred L. Johnson Corresponding Secretary and Librarian Henry B. Carrington, 19 Summer Street, Hyde Park, Mass. Treasurer Henry B. Humphrey Editor William A. Mowry, 17 Riverside Square, Hyde Park, Mass. Curators Amos H. Brainard Frank B. Rich George L. Richardson J. Roland Corthell. George L. Stocking Alfred F. Bridgman Charles F. Jenney Henry B, Carrington {ex ofido) CONTENTS OF VOLUME IV. THEODORE DWIGHT WELD 5-32 IVi'lliam Lloyd Garrison, "J-r., Charles G. Chick, Henry B. Carrington, Mrs. Albert B. Bradley, Mrs. Cordelia A. Pay- son, Wilbur H. Po'vers, Francis W. Darling; Edtvard S. Hathazvay. JOHN ELIOT AND THE INDIAN VILLAGE AT NATICK . 33-48 Erastus Worthington. GOING WEST IN 1820. George L. Richardson .... 49-67 EDITORIAL. William A. Mowry 68 JACK FROST (Poem). William A. Mo-vry 69 A HYDE PARK MEMORIAL, 18SS (with Ode) .... 70-75 Henry B- Carrington. HENRY A. RICH 76, 77 William y. Stuart, Robert Bleakie, Henry S. Bunton. DEDICATION OF CAMP MEIGS (1903) 78-91 Henry B. Carrington, Augustus S. Lovett, BetiJ McKendry. PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY SINCE 1892 . 92-100 Fred L. 'Johnso7i. John B. Bachelder. Henry B- Carrington, Geo. M. Harding, yohn y. E7ineking ..... 94, 95 Gov. F. T. Greenhalge. C. Fred Allen, John H. ONeil . 96 Annual Meeting, 1897. Charles G. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

The Legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Michael J. Puglisi College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Puglisi, Michael J., "The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623769. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-f5eh-p644 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. -

The Narragansett Planters 49

1933.] The Narragansett Planters 49 THE NARRAGANSETT PLANTERS BY WILLIAM DAVIS MILLER HE history and the tradition of the "Narra- T gansett Planters," that unusual group of stock and dairy farmers of southern Rhode Island, lie scattered throughout the documents and records of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and in the subse- quent state and county histories and in family genealo- gies, the brevity and inadequacy of the first being supplemented by the glowing details of the latter, in which imaginative effort and the exaggerative pride of family, it is to be feared, often guided the hand of the chronicler. Edward Channing may be considered as the only historian to have made a separate study of this community, and it is unfortunate that his monograph. The Narragansett Planters,^ A Study in Causes, can be accepted as but an introduction to the subject. It is interesting to note that Channing, believing as had so many others, that the unusual social and economic life of the Planters had been lived more in the minds of their descendants than in reality, intended by his monograph to expose the supposed myth and to demolish the fact that they had "existed in any real sense. "^ Although he came to scoff, he remained to acknowledge their existence, and to concede, albeit with certain reservations, that the * * Narragansett Society was unlike that of the rest of New England." 'Piiblinhed as Number Three of the Fourth Scries in the John» Hopkini Umtertitj/ Studies 111 Hittirieal and Political Science, Baltimore, 1886. "' l-Mward Channing^—came to me annoiincinn that he intended to demolish the fiction thiit they I'xistecl in any real Bense or that the Btnte uf society in soiithpni Rhode Inland iliiTcrpd much from that in other parts of New EnRland. -

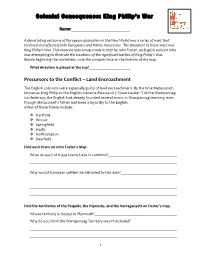

Colonial Consequence: King Philip’S War

Colonial Consequence: King Philip’s War Name: A devastating outcome of European colonialism in the New World was a series of wars that involved and affected both Europeans and Native Americans. The bloodiest of these wars was King Philip’s War. This exercise uses a map made in 1677 by John Foster, an English colonist who was attempting to illustrate the locations of the significant battles of King Philip’s War. Before beginning the worksheet, note the compass rose on the bottom of the map. What direction is placed at the top?_____________________ Precursors to the Conflict – Land Encroachment The English colonists were especially guilty of land encroachment. By the time Metacomet, known as King Philip to the English, became Massasoit (“Great Leader”) of the Wampanoag Confederacy, the English had already founded several towns in Wampanoag territory, even though Metacomet’s father had been a loyal ally to the English. A few of these towns include: Hartford Winsor Springfield Hadly Northampton Deerfield Find each town on John Foster’s Map. What do each of these towns have in common? Why would European settlers be attracted to this area? Find the territories of the Pequids, the Nipnucks, and the Narragansett on Foster’s map. Whose territory is closest to Plymouth? Why do you think the Wampanoag Territory wasn’t included? 1 Precursors to the Conflict – Suspicions and Rumors Metacomet’s older brother, Wamsutta, had been Massasoit for only a year when he died suspiciously on his way home from being detained by the governor of Plymouth Colony. Metacomet, already distrustful towards Europeans, likely suspected the colonists of assassinating his brother. -

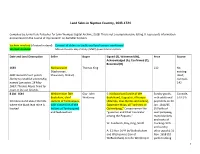

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Vital Allies: the Colonial Militia's Use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2011 Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676 Shawn Eric Pirelli University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Pirelli, Shawn Eric, "Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676" (2011). Master's Theses and Capstones. 146. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VITAL ALLIES: THE COLONIAL MILITIA'S USE OF iNDIANS IN KING PHILIP'S WAR, 1675-1676 By Shawn Eric Pirelli BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2008 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In History May, 2011 UMI Number: 1498967 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 1498967 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. -

The Life and Times of Kateri Tekakwitha

[10][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][11][1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] [Pg vi]vii]viii]ix]xiv]2]3]4]5]6]7]8]9]10]11]12]13]14]15]16]17]18]19]20]21]22]23]24]25]26]27]28]29]30]31]32]33]34]35]36]37]38]39]40]41]42]43]44]45]46]47]48]49]50]51]52]53]54]55]56]57]58]59]60]61]62]63]64]65]66]67]68]69]70]71]72]73]74]75]76]77]78]79]80]81]82]83]84]85]86]87]88]89]90]91]92]93]94]95]96]97]98]99]100]101]102]103]104]105]106]107]108]109]110]111]112]113]114]115]116]117]118]119]120]121]122]123]124]125]126]127]128]129]130]131]132]133]134]135]136]137]138]139]140]141]142]143]144]145]146]147]148]149]150]151]152]153]154]155]156]157]158]159]160]161]162]163]164]165]166]167]168]169]170]171]172]173]174]175]176]177]178]179]180]181]182]184]185]186]187]188]189]190]191]192]193]194]195]196]197]198]199]200]201]202]203]204]205]206]207]208]209]210]211]212]213]214]215]216]217]218]219]220]221]222]223]224]225]226]227]228]229]230]231]232]233]234]235]236]237]238]239]240]241]242]243]244]245]246]247]248]249]250]251]252]253]254]255]256]257]258]259]260]261]262]263]264]265]266]267]268]269]270]271]272]273]274]275]276]277]278]279]280]281]282]283]284]285]286]287]288]289]290]291]292]293]294]295]296]297]298]299]302]303]304]305]306]307]308]309]310]311]312]313]314] THE LIFE AND TIMES [Pg 183] OF KATERI TEKAKWITHA, 1656-1680. -

Assessment of Cancer Incidence in Canton, Massachusetts 1982-1992

9/15/97 PUBLIC COMMENT RELEASE Health Consultation: Assessment of Cancer Incidence in Canton, Massachusetts 1982-1992 September 15, 1997 Public Comment Release Bureau of Environmental Health Assessment, Community Assessment Unit TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: BACKGROUND AND STATEMENT OF ISSUES II. CANCER INCIDENCE ANALYSIS A. METHODS FOR ANALYZING CANCER INCIDENCE DATA B. CANCER INCIDENCE IN CANTON 1. Cancer Incidence in Canton as a Whole (Tables 1A & 1B) 2. Census Tract 4151 (Tables 2A & 2B) 3. Census Tract 4152 (Tables 3A & 3B) 4. Census Tract 4153 (Tables 4A & 4B) C. GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION D. SMOKING STATUS AND OCCUPATION III. ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS A. BACKGROUND - DEMOGRAPHICS, LAND USE, AND NATURAL RESOURCES USE B. SITE DESCRIPTION AND HISTORY 1. Indian Line Farm (MDEP Site # 3-0283, USEPA Site # MAD980503528) 2. The Ponkapoag Golf Course (MDEP Site # 3-11044) 3. Toka-Renbe Farm (MDEP Site # 3-0284, USEPA Site # MAD981063084) 4. The Sutcliff Avenue Neighborhood (MDEP Site #3-125334) 5. The King’s Road Neighborhood IV. DISCUSSION A. KIDNEY CANCER B. LEUKEMIA C. MELANOMA D. NON-HODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA E. ENVIRONMENTAL DATA V. LIMITATIONS VI. CONCLUSIONS VII. RECOMMENDATIONS VIII. REFERENCES IX. APPENDICES A. FACT SHEET: POLYCHLORINATED BIPHENYLS (PCBS) IN CANTON, MA B. GENERAL DISCUSSION ON THE ETIOLOGY OF SELECTED CANCER TYPES 2 9/15/97 PUBLIC COMMENT RELEASE I. INTRODUCTION: BACKGROUND AND STATEMENT OF ISSUES At the request of concerned citizens and the Canton Board of Health, the Community Assessment Unit (CAU) of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH), Bureau of Environmental Health Assessment (BEHA), analyzed cancer incidence in Canton, Massachusetts. This analysis was conducted under a cooperative agreement with the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). -

Indigenous Reactions to Religious Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century New England, New France, and New Mexico

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2020 Our Souls are Already Cared For: Indigenous Reactions to Religious Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century New England, New France, and New Mexico Gail Coughlin University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Canadian History Commons, European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Latin American History Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Other History Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Coughlin, Gail, "Our Souls are Already Cared For: Indigenous Reactions to Religious Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century New England, New France, and New Mexico" (2020). Masters Theses. 898. https://doi.org/10.7275/17285938 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/898 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Our Souls Are Already Cared For: Indigenous Reactions to Religious Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century New England, New France, and New Mexico A Thesis Presented by GAIL M. COUGHLIN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree