Download PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lent & Easter Season

LENT/EASTER SEASON February 22, 2015 WHAT’S THIS? At its root, Lent is a name for Spring, and is a 40-day period of preparation for Easter Sunday and one of the major liturgical seasons of the Catholic Church. A penitential season marked by prayer, fasting and abstinence, and almsgiving, Lent begins on Ash Wednesday and ends on Holy Saturday. The color of Lent is purple; The six Sundays in Lent are not part of the Lenten fast, and thus we say there are 40 days of Lent – a biblical number – while there are really 46; The Stations of the Cross are a devotion imitating a pilgrimage with Jesus to commemorate 14 key events around the crucifixion; Because of the solemnity of Lent, the Gloria and Alleluia are not said or sung. March 1, 2015 WHAT’S THIS? During Lent the Church is called to embrace a spirit of repentance and metanoia (“a change of heart”) or conversion. There are many opportunities for prayer – communally or individually – such as: Daily Mass (communal) Stations of the Cross (communal and individual) The Rosary (communal and individual) Liturgy of the Hours (individual) Reconciliation (communal and individual) Adoration of the Eucharist in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel every Friday (individual) Free web Lent program offered by Dynamic Catholic—sign up at BestLentEver.com. March 8, 2015 WHAT’S THIS? The next four weeks of “What’s This” will be highlighting specific components that lead up through the Easter Vigil. Palm Sunday – March 29: The liturgical color of Palm Sunday is red. Red signifies Christ’s Passion; The Palm Sunday liturgy begins with an additional Gospel highlighting the jubilant entrance of Jesus into Jerusalem; The palms are ancient symbols of victory and hope, as well as new life; The Palm Sunday liturgy takes on a more somber tone with the second Gospel reading of Christ’s Passion; The blessed palms received this day should be discarded as other blessed articles. -

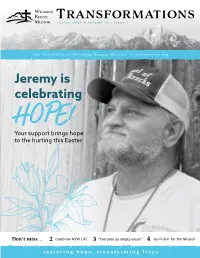

Easter 2021 • Volume 16 | Issue 1

WYOMING RESCUE MISSION Easter 2021 • Volume 16 | Issue 1 Sunday, April 4: Our Easter Celebration The Newsletter of Wyoming Rescue Mission • wyomission.org from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m.! Jeremy is celebrating HOPE! Your support brings hope to the hurting this Easter. Don’t miss… 2 Celebrate NEW LIFE 3 “I’ve been an empty vessel.” 4 Go Fishin’ for the Mission restoring hope, transforming lives “I came that you may have life and have it abundantly.” - John 10:10, NASB A Message from BRAD HOPKINS ANNUAL EASTER CAMPAIGN Celebrate hope by caring for THE MIRACLE OF EASTER our most vulnerable neighbors! lives on in you 5,148 meals Can you imagine what it must broken… every heart that turns to have been like to gaze into that Him… every life that’s restored is a empty tomb that Easter morning? cause for rejoicing. $2.15 for a meal! To rise from the depths of despair And it’s all thanks to caring to heart-pounding, indescribable friends like you! 4,633 nights joy… realizing Jesus conquered the This Easter, I pray that you will of shelter grave? see God move mightily in your That’s the power of the own life, just as you have given resurrection. And that same power generously so He can work miracles 50 men & women is still transforming hearts and lives in the lives of your neighbors like in our recovery today. Jeremy (whose incredible story is programs (on Jesus came that we may have on page 3). average) life abundantly, and we embrace May our hearts be as one as we that as our calling. -

Why Is It Called Easter?

March 20, 2018 Why Is It Called Easter? Easter is the name of the most important Christian holiday, the day we celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead after his crucifixion. The resurrection of Jesus resides at the very heart of the gospel: “For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures” (1 Cor. 15:3-4). But, why is this holiday called Easter? Where did the name Easter come from? Let’s shed some light on those questions. Easter is an English word The etymology of the English word Easter indicates that it descends from the Old German—likely from root words for dawn, east, and sunrise. English is a western Germanic language named for the Angles who, along with the Saxons (another Germanic tribe), settled Britain in the 5th century. In fact, the Old German for Easter was Oster (Ostern in the modern). English and German speakers have been using variations of the term Easter for over a millennium. However, most of the countries surrounding Britain and the German principalities of Europe have long used variants of the Latin Pascha (from the Greek for Passover, a transliteration of the Hebrew pesach) as the name of the celebration of Christ’s resurrection. Today, in many non-English speaking countries, Easter is still called by a name derived from the term Pashca. A number of other languages use a term that means Resurrection Feast or Great Day. -

Read an Excerpt

A LEGENDARY CHRISTMAS ________________________ A musical fable in 12 scenes. Book and lyrics by David C. Field Music by Michael Silversher www.youthplays.com [email protected] CAST OF CHARACTERS THE MAN IN THE MOON BIG MOMMA THE APRIL FOOL THE STORK JACK FROST THE SANDMAN THE TOOTH FAIRY THE HALLOWEEN WITCH THE EASTER BUNNY THE MARCH LION FATHER TIME SANTA CLAUS SCENE 1 SCENE: Limbo TIME: The present. At Rise: FUNKY MUSIC. The disembodied face of the MAN IN THE MOON appears. MOON (Scat sings) ZAT. SHA-BOOM, ZA-BAM, ETC. (Intro:) I AM THE MOON, MAN. THE CELESTIAL NIGHT LIGHT, THE SILVER SENTINEL OF THE SKY, WAXIN' AND WANIN' AND TURNIN' THE TIDES, SLIPPIN' AND SLIDIN' THROUGH THE CIRROCUMULUS, AND I GOT MORE MYTHOLOGY IN ME THAN MUTHA GOOSE. I AM THE MOON, MAN, AND I AM RISING. IT'S DECEMBER TWENTY-TWO, AND FROM MY MOON'S EYE VIEW, THE VIBES I'M GETTING ARE TROUBLIN’. TO DE-FUZZIFY WHAT’S BUBBLIN’, LET US BOP DOWN THE ROAD TO THE COZY ABODE OF THE HOSTESS OF OUR DRAMA. YOU CALL HER MOTHER NATURE. WE CALL HER BIG MOMMA. Lights out on the Moon. END OF SCENE 1 © David C. Field & Michael Silversher This is a perusal copy only. Absolutely no copying permitted. 2. SCENE 2 Lights up on Big Momma's Health Bar. The ”Big Momma’s” sign is on the upstage wall. The bar, with holiday décor, is upstage center. Downstage on either side are chairs mounted upside down on tables. BIG MOMMA enters and begins fussing with the décor. -

Christmas and Easter Mini Test

Name: Date: 15 total marks Celebrations around the World: Christmas and Easter Mini Test 1. Name at least two countries where Christmas is celebrated. 21 marksmark 2. True or False? Christmas is always celebrated on 25th December. 1 mark 3. In Ethiopia, many people play a game called gena. What is gena? 1 mark 4. In Denmark, when do people celebrate the Christmas feast? 1 mark 5. In Mexico, what are set up several weeks before Christmas Day? 1 mark 6. In India, what do Christians decorate at Christmas time? 1 mark 7. Who introduced Christmas and Easter to Japan? 1 mark total for this page History | Year 3 | Celebrations around the World | Christmas and Easter | Lesson 6 8. Name at least two countries where Easter is celebrated. 2 marks 9. In Spain, why do people draw ash crosses on their foreheads? 1 mark 10. In the USA, where is an Easter egg rolling event held every year? 1 mark 11. In what country would you find Easter eggs hung on trees? 1 mark 12. Share one similarity between how you and how other people from around the world celebrate Easter. 1 mark 13. In your opinion, what does the Easter egg represent? 1 mark total for **END OF TEST** this page History | Year 3 | Celebrations around the World | Christmas and Easter | Lesson 6 Celebrations around the World: Christmas and Easter Mini Test Answers 1 Australia, Ethiopia, France, Denmark, Mexico, India, Japan 2 marks 2 False 1 mark 3 Gena is a kind of hockey. According to Ethiopian legend, gena was the 1 mark game played by the shepherds the night Jesus was born in Bethlehem. -

Vernal Equinox 25Th- Palm Sunday 30Th

2018 2019 2020 2021 January- None January- None January January- None February February 25th- Chinese New Year February 14th- Ash Wednesday 5th- Chinese New Year February 12th- Chinese New Year 16th- Chinese New Year March 26th- Ash Wednesday 17th- Ash Wednesday March 6th- Ash Wednesday March March 20th- Vernal Equinox 20th- Vernal Equinox 20th- Vernal Equinox 20th- Vernal Equinox 25th- Palm Sunday April April 28th- Palm Sunday 30th- Good Friday 14th- Palm Sunday 5th- Palm Sunday Passover* 30th- Passover 19th- Good Friday 9th- Passover* April April 20th- Passover 10th- Good Friday 2nd - Good Friday 1st- Easter 21st- Easter 12th- Easter 4th- Easter May May 24th-May 23rd- 13th-May 12rd- Ramadan** Ramadan** 16th-June 15th- Ramadan** 6th-June 4th- Ramadan** May May 20th- Shavuot* June 1st-23rd- Ramadan** 1st-12rd- Ramadan** June 1st-4th- Ramadan** 24th- Eid al-Fitr** 13th- Eid al-Fitr** 1st-15th- Ramadan** 5th- Eid al Fitr** 29th- Shavuot* 17th- Shavuot* 15th- Eid al Fitr** 9th- Shavuot* June-None June-None July-None July-None July July August August 31st- Eid al-Adha** 20st- Eid al-Adha** 22th- Eid- al-Adha** 12th- Eid- al-Adha** August- none August- none September September September September 10th-11th- Rosh Hashanah* 29th-30th- Rosh Hashanah* 18th-19th- Rosh Hasanah* 7th-8th- Rosh Hasanah* 19th- Yom Kippur* October 27th- Yom Kippur* 16th- Yom Kippur* 24th- Sukkot* 8th- Yom Kippur* October 21st- Sukkot* October-None 14th- Sukkot* 3rd- Sukkot* October-None November 27th- Diwali November November 7th- Diwali November- None 14th- Diwali 4th- Diwali December December December 29th- Chaunukah* 3rd- Chaunukah* 23rd- Chaunukah* 11th- Chaunukah* December 25th- Christmas Day 25th- Christmas Day 25th- Christmas Day 25th- Christmas Day 26th- Kwanzaa 26th- Kwanzaa 26th- Kwanzaa 26th- Kwanzaa Faith Description Chinese New Begins a 15-day festival for Chinese people of all religions. -

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson Introduction Sociologist Bryan R. Wilson once alleged that post-modern technology and secularisation are the allied forces of rationality and disenchantment that pose an immense threat to traditional religion.1 However, the flexibility of pastiche Neopagan belief systems like ‘Witchcraft’ have creativity, fantasy, and innovation at their core, allowing practitioners of Witchcraft to respond in a unique way to the post-modern age by integrating technology into their perception of the sacred. The phrase Deus ex Machina, the God out of the Machine, has gained a multiplicity of meanings in this context. For progressive Witches, the machine can both possess its own numen and act as a conduit for the spirit of the deities. It can also assist the practitioner in becoming one with the divine by enabling a transcendent and enlightening spiritual experience. Finally, in the theatrical sense, it could be argued that the concept of a magical machine is in fact the contrived dénouement that saves the seemingly despondent situation of a so-called ‘nature religion’ like Witchcraft in the techno-centric age. This paper explores the ways two movements within Witchcraft, ‘Technopaganism’ and ‘Technomysticism’, have incorporated man-made inventions into their spiritual practice. A study of how this is related to the worldview, operation of magic, social aspect and development of self within Witchcraft, uncovers some of the issues of longevity and profundity that this religion will face in the future. Witchcraft as a Religion The categorical heading ‘Neopagan’ functions as an umbrella that covers numerous reconstructed, revived, or invented religious movements, that have taken inspiration from indigenous, archaic, and esoteric traditions. -

Nochebuena Navidad

Sacred Heart Church, 200 So. 5th St. St. Mary’s Church, 2300 W. Madison Ave. Sacred Heart Parish Center, 2301 W. Madison Ave. Sacred Heart Parish Office 204 So. 5th St. 402-371-2621 Nochebuena Dic 24: 3:50 p.m. Proseción de Niños, Sta María 4:00 pm Sta. María 6:00 pm Sta. María 11:00 pm Música Navideña, Sta. María 12:00 pm Misa de Medianoche, Sta. María 4:00 pm St. Leonard, Madison 6:00 pm St. Leonard, Madison (bilingüe) 6:00 pm St. Peter’s, Stanton Navidad Dic 25: 8:30 am Sta. María 10:30 am Sta. María (bilingüe) 9:00 am St. Leonard, Madison 10:00 am St. Peter’s, Stanton PARISH LITURGIES Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament Teen Ministry Saturday Eve Vigil Masses St. Mary’s Church Lynnette Otero, 402-371-2621 St. Mary’s Church 24/7 every day RELIGIOUS FORMATION 5:00 pm Reconciliation 204 So. 5th St. 402-371-2621 Sunday Masses Sacred Heart Church IMMACULATA MONASTERY Sacred Heart Church 4:45 pm-5:20 pm (M-T-W-Th-F) & SPIRITUALITY CENTER 7:30 am St. Mary’s Church 300 No. 18th St. 402-371-3438 Masses: S-M-T-W-F-Sa: 7:00 am; Th-5:00 pm St. Mary’s Church 4:00 pm-4:45 pm (Saturday) Holy day Masses: 7:00 am 9:30 am, 11:30 am PARISH WEB SITE: Vespers: 5:30 pm daily (Thursday-5:00 pm) Weekday Masses www.SacredHeartNorfolk.com Monastery Website: www.mbsmissionaries.org. (Please check page 4 for changes) NORFOLK CATHOLIC SCHOOL ST. -

Happy Easter May Your Easter Be Happy, May Your Day Be Bright, May You Enjoy the Treats, and Sweets Delights

Happy Easter May your Easter be happy, May your day be bright, May you enjoy the treats, And sweets delights. But remember the meaning, Remember God’s gift, Remember the resurrection, May your soul uplift. Easter Message Easter morning bright and fair Tells me of God’s loving care. Flowers that were gone from view Now awakening, bloom anew. Though God’s face I do not see, I will trust His care for me. Jesus Lives Just because He loved us so Jesus died once long ago. But He rose on Easter Day, Now let all his children say: “Jesus lives! Jesus lives! Oh, I’m happy! Jesus lives!” Just because He loved us so Jesus died once long ago. But He rose on Easter Day, Now let all his children say: “Jesus lives! Jesus lives! Oh, I’m happy! Jesus lives!” Easter Day Christ the Lord is risen today! Angels rolled the stone away From the tomb wherein He Lay Little children, come and sing, “Glory, glory, to the King, Christ the Lord of everything!” He Lives I serve a risen Savior He’s in the world today. I know that He is living Whatever men may say. I see His hand of mercy; I hear His voice of cheer; And just the time I need Him He is always near. Jesus Rose on Easter Day Jesus rose on Easter day, The stone by his tomb was rolled away. He conquered death upon that day, And He lives again to show us the way. The Cross My small mind can’t comprehend, My simple heart can’t understand, My humble soul can’t take it in- The glory of the cross. -

Year of St. Joseph

YEAR OF ST. JOSEPH Sunday, August 16th - Saturday, May 1st Pastoral Guide for Celebrating the Year of St. Joseph BISHOP’S PASTORAL LETTER August ‘20 | Joseph and the TABLE OF CONTENTS I. WHY ST. JOSEPH? WHY NOW? II. OPENING WEEKEND CELEBRATION (AUGUST 15-16) III. PRAYERS AND LITURGY IV. INDULGENCES V. ACTIVITIES AND IDEAS VI. PARISH PILGRIMAGE SITES VII. BISHOP PASTORAL LETTER VIII. CATECHETICAL RESOURCES IX. APPENDIX I. WHY ST. JOSEPH? WHY NOW? On December 8, 1870, The Sacred Congregation of Rites promulgated the following decree, which communicated the decision of Pope Pius IX to declare St. Joseph Patron of the Universal Church, and which also raised St. Joseph’s feast of March 19 to the rank of double of the first class. Quemadmodum Deus Pope Pius IX As almighty God appointed Joseph, son of the patriarch Jacob, over all the land of Egypt to save grain for the people, so when the fullness of time had come and he was about to send to earth his only- begotten Son, the Savior of the world, he chose another Joseph, of whom the first had been the type, and he made him the lord and chief of his household and possessions, the guardian of his choicest treasures. Indeed, he had as his spouse the Immaculate Virgin Mary, of whom was born by the Holy Spirit, Jesus Christ our Lord, who deigned to be reputed in the sight of men as the son of Joseph, and was subject to him. Him whom countless kings and prophets had desired to see, Joseph not only saw but conversed with, and embraced in paternal affection, and kissed. -

Eostre in Britain and Around the World

I was delighted to recent- Eostre in Britain and ly discover that many of Around the World the Iranians who escaped from Khomeni’s funda- mentalist Islamic rule of 01991, Tana Culain ‘K’A’M terror into exile - and no doubt many still trapped - are actually quite Pa- I t is no coincidence that and the Old German Eos- gan in their beliefs. A the Spring Equinox, tre, Goddess of the East. friend of mine was kind Passover, and Easter all Eostre was originally the enough to explain to me fall at the same time of name of the prehistoric that March 21 remains year. west Germanic Pagan Noruz, the ancient Per- spring festival, which is sian New Year. Many Per- The Christian Easter is a not to say that this same sians grow new seeds at lunar holiday and always festival was not celebrated this time of year and each falls on the first Sunday world over by many other family member must after the first full moon af- names. jump over seven fires ter the Spring Equinox. If made of thorns and bush- the full moon is on a Sun- es in a purification ritual. day, Easter is the next Special treats of seven Sunday. Why don’t the dried fruits and nuts are powers that be allow East- given out, and eggs are er to occur on a full moon colored and put on a fam- Sunday? Probably the ily altar alongside a mir- Christian Easter is too ror, coins, sprouted masculine a day, being grains, water, salt, and tu- the resurrection of a mon- lips. -

1 March 2021 Diversity/Cultural Events

MARCH 2021 DIVERSITY/CULTURAL EVENTS & CELEBRATIONS Women’s History Month National Women’s History Month began as a single week and as a local event. In 1978, Sonoma County, California, sponsored a women’s history week to promote the teaching of women’s history. The week of March 8 was selected to include “International Women’s Day.” This day is rooted in such ideas and events as a woman’s right to vote and a woman’s right to work, women’s strikes for bread, women’s strikes for peace at the end of World War I, and the U.N. Charter declaration of gender equality at the end of World War II. This day is an occasion to review how far women have come in their struggle for equality, peace and development. In 1981, Congress passed a resolution making the week a national celebration, and in 1987 expanded it to the full month of March. The 2021 theme is Valiant Women of the Vote: Refusing to be Silenced continues to celebrate the Suffrage Centennial” celebrates the women who have fought for woman’s right to vote in the United States. For more information visit http://www.nwhp.org/. Irish American Heritage Month A month to honor the contributions of over 44 million Americans who trace their roots to Ireland. Celebrations include celebrating St. Patrick’s Day (March 17th) with parades, family gathering, masses, dances, etc. Due to COVID-19, many of these events have been cancelled. For more information visit the Irish-American Heritage Month website at http://irish-american.org/.