Reply to Enrichment of Regulatory Motifs Upstream of Predicted DAF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symposium on Aging June 19, 2015 Symposium on Aging the Paul F

The 2015 Harvard / Paul F. Glenn Symposium on Aging June 19, 2015 Symposium on Aging The Paul F. Glenn Laboratories for the Biological Mechanisms of Aging Agenda 10th Anniversary Symposium Welcome to the 10th Annual Harvard/Paul F. Glenn Symposium on Aging. June 19, 2015 Each year, the Paul F. Glenn Laboratories host the Harvard Symposium 9:00 - 5:00 on Aging with a mission to present new advances in aging research and to stimulate collaborative research in this area. The symposium has grown over the past 10 years to be one of the biggest events at Harvard Medical School. We have been fortunate to have many of the leaders in the aging field speak 9:00 – 9:45 a.m. Introduction at the symposia and today is no exception. We wish to acknowledge the generosity and vision of Paul F. Glenn, Mark 9:45 – 10:15 a.m. Ensuring the Health of the Germ-line Collins and Leonard Judson for their unwavering support of aging research Cynthia Kenyon, Ph.D. through the Paul F. Glenn Foundation. Thanks to their support, we now have a vibrant community of researchers who study aging and age-related 10:15 – 10:45 a.m. C. elegans Surveillance of Core Cellular diseases. Since the inception of the Paul F. Glenn labs at Harvard in 2005, Components to Detect and Defend Pathogen this network has grown to include aging studies at the Albert Einstein Attacks, and How This Relates to Longevity College of Medicine, the Buck Institute, the Mayo Clinic, Massachusetts Gary Ruvkun, Ph.D. -

David Sinclair Can Dramatically Extend the Life Span of Yeast

News Focus Lenny Guarente and his former postdoc David Sinclair can dramatically extend the life span of yeast. They’re battling over how this works, and competing head-to-head to grant extra years to humans Aging Research’s Family Feud BOSTON AND CAMBRIDGE,MASSACHUSETTS—At tenure-track spot on Harvard’s faculty in late share many traits common among successful 34, David Sinclair is a rising star. His spa- 1999. He then made clear that his old profes- scientists. Both are deeply ambitious, relent- cious ninth-floor office at Harvard Medical sor’s pet theories weren’t off limits. At a lessly competitive, and supremely self-confi- School boasts a panoramic Boston view. His meeting at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory dent. Both savor the limelight. Both love sci- rapidly growing lab pulled off the feat of pub- in late 2002, Sinclair surprised Guarente by ence and show little interest in other pursuits. lishing in both Nature and Science last year, challenging him on how a key gene Guarente Still, they’ve retained something of the and it made headlines around the world with discovered extends life in yeast. That sparked parent-child relationship that can shape in- a study of the possible antiaging properties of a bitter dispute that crescendoed this winter, teractions between senior researchers and a molecule found in red wine. In a typical when the pair published dueling papers. their students. Like a father dismayed when day, he fields calls from a couple practicing a Researchers who study aging are finding his son joins a punk rock band, and then dis- radical diet to extend life span, and from an the quarrel both intellectually provocative and mayed further when it attracts devoted fans actor hunting for antiaging pills and the a lively source of gossip. -

Genes That Act Downstream of DAF-16 to Influence the Lifespan Of

articles Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans Coleen T. Murphy*, Steven A. McCarroll†, Cornelia I. Bargmann†, Andrew Fraser‡, Ravi S. Kamath‡, Julie Ahringer‡, Hao Li* & Cynthia Kenyon* * Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, and † Department of Anatomy and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, San Francisco, California 94143-2200, USA ‡ Wellcome CRC Institute and Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge, Tennis Court Road, Cambridge CB2 1QR, UK ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Ageing is a fundamental, unsolved mystery in biology. DAF-16, a FOXO-family transcription factor, influences the rate of ageing of Caenorhabditis elegans in response to insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I) signalling. Using DNA microarray analysis, we have found that DAF-16 affects expression of a set of genes during early adulthood, the time at which this pathway is known to control ageing. Here we find that many of these genes influence the ageing process. The insulin/IGF-I pathway functions cell non- autonomously to regulate lifespan, and our findings suggest that it signals other cells, at least in part, by feedback regulation of an insulin/IGF-I homologue. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the insulin/IGF-I pathway ultimately exerts its effect on lifespan by upregulating a wide variety of genes, including cellular stress-response, antimicrobial and metabolic genes, and by downregulating specific life-shortening genes. The recent discovery that the ageing process is regulated hormonally never been tested directly; for example, by asking whether stress by an evolutionarily conserved insulin/IGF-I signalling pathway1–3 response genes are required for the longevity of daf-2 mutants. -

From Here to Immortality: Anti-Aging Medicine

FromFrom HereHere toto Immortality:Immortaalitty: AAnti-AgingAnnntti-AAgging MMedicineedicine Anti-aging medicine is a $5 billion industry. Despite its critics, researchers are discovering that inter ventions designed to turn back time may prove to be more science than fiction. By Trudie Mitschang 14 BioSupply Trends Quarterly • October 2013 he symptoms are disturbing. Weight gain, muscle Shifting Attitudes Fuel a Booming Industry aches, fatigue and joint stiffness. Some experience The notion that aging requires treatment is based on a belief Thear ing loss and diminished eyesight. In time, both that becoming old is both undesirable and unattractive. In the memory and libido will lapse, while sagging skin and inconti - last several decades, aging has become synonymous with nence may also become problematic. It is a malady that begins dete rioration, while youth is increasingly revered and in one’s late 40 s, and currently 100 percent of baby boomers admired. Anti-aging medicine is a relatively new but thriving suffer from it. No one is immune and left untreated ; it always field driven by a baby- boomer generation fighting to preserve leads to death. A frightening new disease, virus or plague? No , its “forever young” façade. According to the market research it’s simply a fact of life , and it’s called aging. firm Global Industry Analysts, the boomer-fueled consumer The mythical fountain of youth has long been the subject of base will push the U.S. market for anti-aging products from folklore, and although it is both natural and inevitable, human about $80 billion now to more than $114 billion by 2015. -

Alchemy of Aging

BOOK REVIEW Alchemy of aging The twists and turns of the discovery of telomerase, the cloning of the gene and the demonstration of its immortalizing Merchants of Immortality: Chasing power in cell culture systems are well told. Along the way, we the Dream of Human Life Extension learn of the squabbles, too. A sad axiom of modern biology, reflects Hall, is that the hotter the field, the ruder the behavior of Stephen S Hall its practitioners. Sad, perhaps, but as Hall very well knows, it Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003 makes for good copy. Although Hall documents his sources exhaustively, in more than 439 pp. hardcover, $25.00 50 pages of notes, his scientific range is limited. For example, he ISBN 0-61809-524-1 does not do as much as is needed to put the telomerase work into context. As the field has advanced, it has emerged that there is much Reviewed by Tom B L Kirkwood more to controlling cell proliferation than telomerase and that there is much more to tissue aging than just the Hayflick Limit. Unquestionably, the work included in Hall’s account is of great sig- nificance. But when and how it might lead to any real prospect of http://www.nature.com/naturemedicine For a work of engaging and painstaking science journalism, one intervention to extend human lifespan is anybody’s guess. Some of would have to search far to find anything that beats Stephen S. Hall’s the most interesting research in the field of aging is being done on Merchants of Immortality.This is the good news. -

Real-Time Egg Laying Dynamics in Caenorhabditis Elegans

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Real-time egg laying dynamics in Caenorhabditis elegans DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Biomedical Engineering by Philip Vijay Thomas Dissertation Committee: Professor Elliot Hui, Chair Professor Olivier Cinquin Professor Abraham Lee 2015 c 2015 Philip Vijay Thomas TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CURRICULUM VITAE vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION viii 1 Introduction and motivation 1 1.1 The impact of C. elegans in aging and lifespan studies along with current limitations . 1 1.2 Starvation and its effect on worms . 4 1.3 Microfabricated systems for C. elegans biology . 5 2 Real-time C. elegans embryo cytometry to study reproductive aging 7 2.1 High capacity low-weight passive bubble trap . 8 2.2 Microfluidic device layout . 10 2.3 Tuning habitat exit sizes to flush out embryos while retaining worms . 11 2.4 Equal flow resistance to make identical habitats . 12 2.5 Video enumeration of eggs . 13 2.6 Switching between discrete and continuously varying media concentrations . 15 3 Optimizing worm health in C. elegans microfluidics 17 3.1 E. coli densities of 1010 cells/mL maintain egg-laying in liquid worm culture 18 3.2 E. coli biofilms in devices . 19 3.3 Amino acid addition to S-media, γ irradiation of bacteria, and elevated syringe temperatures are ineffective in reducing biofilms in devices . 20 3.4 Use of a curli major subunit deletion strain significantly reduces biofilm in S-media . 23 4 Conclusions and future directions 26 Bibliography 30 ii A Appendix Title 41 A.1 Methods . -

11/05/09 Agenda Attachment 6

Bioinformatics @ UCSF: Faculty Multidisciplinary graduate study in biological composition, structure, David Agard function and evolution at the [email protected] molecular and systems levels Professor, Biochemistry & Biophysics Apply Now Structure, function, and folding of proteins, chromosomes, and About the Program centrosomes Training Program: Program Overview Core Curriculum Nadav Ahituv Electives [email protected] Seminars & Journal Club Assistant Professor, Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences Academic Progression & Procedures Deciphering the role of gene regulatory sequences in human People: biology and disease Students Faculty Alumni Patricia Babbitt Current Events [email protected] Admission Information Professor, Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences and Links Pharmaceutical Chemistry Contact Computational and experimental analysis of protein NEWS: UCSF wins HHMI Award for its superfamilies for functional inference and enzyme design Integrative Program in Complex Biological Systems Bruce Conklin [email protected] Associate Professor, Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, Medicine & Pharmacology Combining the tools of molecular biology, genetics, bioinformatics, and physiology to answer fundamental issues in pharmacology. Joe DeRisi [email protected] Hughes Investigator, Associate Professor, Biochemistry & Biophysics Malaria gene expression profiling, functional genomics, microarrays Ken Dill [email protected] Professor, Pharmaceutical Chemistry Statistical mechanics of biomolecules, protein -

Curriculum Vitae K. Adam Bohnert Education 2003-2007 BS, Summa

Curriculum Vitae K. Adam Bohnert Education 2003-2007 BS, summa cum laude, Biology, Rhodes College, Memphis, TN 2007-2013 PhD, Cell & Developmental Biology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 2013-2017 Postdoctoral training, Dr. Cynthia Kenyon’s laboratory, University of California, San Francisco, and Calico Life Sciences, San Francisco Bay Area, CA Research Experience 2005-2006 NSF-REU Intern, Dr. Costantino Vetriani’s laboratory, Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Research topic: Microbial diversity at deep-sea hydrothermal vents 2005-2007 Undergraduate Student Research Assistant, Dr. Rosanna Cappellato’s laboratory, Department of Biology, Rhodes College Research topic: Ecosystem services of urban forests 2007-2013 Graduate Student, Dr. Kathleen Gould’s laboratory, Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, Vanderbilt University Research topic: Control of cell growth and division in fission yeast 2013-2017 Postdoctoral Scholar and Jane Coffin Childs Fellow, Dr. Cynthia Kenyon’s laboratory, University of California, San Francisco, and Calico Life Sciences Research topic: Germline rejuvenation in C. elegans Honors, Awards, and Research Support 2003-2007 National Merit Scholarship 2003-2007 Morse Scholarship (full-tuition scholarship), Rhodes College 2004 Award for Excellence in First-Year Biology, Rhodes College 2006 Michael E. Hendrick Award for Organic Chemistry, Rhodes College 2006-2007 Barry M. Goldwater Scholarship 2007 Outstanding Biology Senior Award, Rhodes College 2007 Phi -

2 the Biology of Ageing

The biology of ageing 2 Aprimer JOAO˜ PEDRO DE MAGALHAES˜ OVERVIEW .......................................................... This chapter introduces key biological concepts of ageing. First, it defines ageing and presents the main features of human ageing, followed by a consideration of evolutionary models of ageing. Causes of variation in ageing (genetic and dietary) are reviewed, before examining biological theories of the causes of ageing. .......................................................... Introduction Thanks to technological progress in different areas, including biomed- ical breakthroughs in preventing and treating infectious diseases, longevity has been increasing dramatically for decades. The life expectancy at birth in the UK for boys and girls rose, respectively, from 45 and 49 years in 1901 to 75 and 80 in 1999 with similar fig- ures reported for other industrialized nations (see Chapter 1 for further discussion). A direct consequence is a steady increase in the propor- tion of people living to an age where their health and well-being are restricted by ageing. By the year 2050, it is estimated that the per- centage of people in the UK over the age of 65 will rise to over 25 per cent, compared to 14 per cent in 2004 (Smith, 2004). The greying of the population, discussed elsewhere (see Chapter 1), implies major medical and societal changes. Although ageing is no longer considered by health professionals as a direct cause of death (Hayflick, 1994), the major killers in industrialized nations are now age-related diseases like cancer, diseases of the heart and 22 Joao˜ Pedro de Magalhaes˜ neurodegenerative diseases. The study of the biological mechanisms of ageing is thus not merely a topic of scientific curiosity, but a crucial area of research throughout the twenty-first century. -

The Genetics of Ageing Cynthia J

INSIGHT REVIEW NATURE|Vol 464|25 March 2010|doi:10.1038/nature08980 The genetics of ageing Cynthia J. Kenyon1 The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans ages and dies in a few weeks, but humans can live for 100 years or more. Assuming that the ancestor we share with nematodes aged rapidly, this means that over evolutionary time mutations have increased lifespan more than 2,000-fold. Which genes can extend lifespan? Can we augment their activities and live even longer? After centuries of wistful poetry and wild imagination, we are now getting answers, often unexpected ones, to these fundamental questions. For many years, molecular biologists interested in regulatory mecha- that dietary restriction is imposed. In C. elegans, for example, one nutrient nisms did not study ageing, as the tissue decline associated with ageing sensor extends lifespan in response to life-long food limitation, another suggested a passive, entropic process of deterioration that occurred in in response to every-other-day feeding and a third if dietary restriction a haphazard way. We know now, however, that the ageing process, like begins in middle age11. so many other biological processes, is subject to regulation by classical Many other conditions can increase lifespan, including heat12–14 and signalling pathways and transcription factors. Many of these pathways oxidative stress15, low ambient temperature, chemosensory signals16, were first discovered in small, short-lived organisms such as yeast, thermosensory signals17, signals from the reproductive system18,19 and worms and flies, but a remarkable fraction turn out to extend lifespan reductions in the rates of respiration19–21 or translation3,22–24. -

Could a Hormone Point the Way to Life Extension?

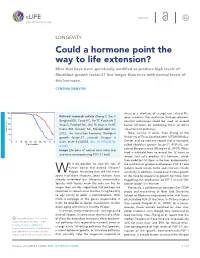

INSIGHT elife.elifesciences.org LONGEVITY Could a hormone point the way to life extension? Mice that have been genetically modified to produce high levels of fibroblast growth factor-21 live longer than mice with normal levels of this hormone. CYNTHIA KENYON stress or a shortage of energy, can extend life- Related research article Zhang Y, Xie Y, span in worms, flies and mice. Perhaps pharma- Berglund ED, Coate KC, He TT, Katafuchi T, ceutical techniques could be used to extend Xiao G, Potthoff MJ, Wei W, Wan Y, Yu RT, human lifespans by modifying these or other Evans RM, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. life-extension pathways. 2012. The starvation hormone, fibroblast Now, writing in eLife, Yuan Zhang of the growth factor-21, extends lifespan in University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical mice. eLife 1:e00065. doi: 10.7554/eLife. Center and co-workers report that a hormone, 00065 called fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF-21), can extend lifespan in mice (Zhang et al., 2012). When Image Lifespans of normal mice (blue line) food is withheld from an animal for 12 hours or and mice overexpressing FGF-21 (red) longer, liver cells produce this hormone, which then mobilizes fat stores in the liver, and promotes ill it be possible to slow the rate of the synthesis of glucose and ketones. FGF-21 also human aging and extend lifespan? reduces basal insulin levels and increases insulin WMaybe. Assuming that the first meta- sensitivity. In addition, it suppresses further growth zoans had short lifespans, gene changes have of the mice by preventing growth hormone from already extended our lifespans dramatically. -

Revisiting the Hayflick Limit

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.03.442497; this version posted May 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Revisiting the Hayflick Limit: Insights from an Integrated Analysis of Changing Transcripts, Proteins, Metabolites and Chromatin. Michelle Chan, Han Yuan*, Ilya Soifer*, Tobias M. Maile, Rebecca Y. Wang, Andrea Ireland, Jonathon O’Brien, Jérôme Goudeau, Leanne Chan, Twaritha Vijay, Adam Freund, Cynthia Kenyon, Bryson Bennett, Fiona McAllister, David R. Kelley, Margaret Roy, Robert L. Cohen, Arthur D. Levinson, David Botstein**, David G. Hendrickson** *contributed equally **Corresponding Authors Abstract Replicative senescence (RS) as a model has become the central focus of research into cellular aging in vitro. Despite decades of study, this process through which cells cease dividing is not fully understood in culture, and even much less so in vivo during development and with aging. Here, we revisit Hayflick’s original observation of RS in WI-38 human fetal lung fibroblasts equipped with a battery of high dimensional modern techniques and analytical methods to deeply profile the process of RS across each aspect of the central dogma and beyond. We applied and integrated RNA-seq, proteomics, metabolomics, and ATAC-seq to a high resolution RS time course. We found that the transcriptional changes that underlie RS manifest early, gradually increase, and correspond to a concomitant global increase in accessibility in nucleolar and lamin associated domains. During RS WI-38 fibroblast gene expression patterns acquire a striking resemblance to those of myofibroblasts in a process similar to the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT).