Review: Sarasota Ballet, with Ashton As the Beating Heart of a Triple Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

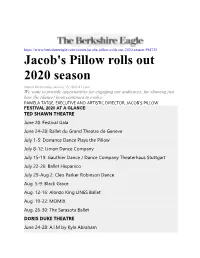

Jacob's Pillow Rolls out 2020 Season

https://www.berkshireeagle.com/stories/jacobs-pillow-rolls-out-2020-season,594735 Jacob's Pillow rolls out 2020 season Posted Wednesday, January 15, 2020 4:15 pm We want to provide opportunities for engaging our audiences; for showing just how the (dance) form continues to evolve.” PAMELA TATGE, EXECUTIVE AND ARTISTIC DIRECTOR, JACOB'S PILLOW FESTIVAL 2020 AT A GLANCE TED SHAWN THEATRE June 20: Festival Gala June 24-28: Ballet du Grand Theatre de Geneve July 1-5: Dorrance Dance Plays the Pillow July 8-12: Limon Dance Company July 15-19: Gauthier Dance / Dance Company Theaterhaus Stuttgart July 22-26: Ballet Hispanico July 29-Aug 2: Cleo Parker Robinson Dance Aug. 5-9: Black Grace Aug. 12-16: Alonzo King LINES Ballet Aug. 19-22: MOMIX Aug. 26-30: The Sarasota Ballet DORIS DUKE THEATRE June 24-28: A.I.M by Kyle Abraham July 1-5: Dorrance Dance Plays the Pillow July 8-12: CONTRA-TIEMPO July 15-19: Duets from Quebec July 22-26: Dance Heginbotham July 29-Aug. 2: Malavika Sarukkai — Thari - The Loom Aug. 5-9: LAVA Companía de Danza Aug. 12-16: Brian Brooks Moving Company Aug. 19-23: Liz Lerman Aug. 26-30: Aszure Barton & Artists By The Berkshire Eagle BECKET — Four programs involving world premieres, three companies making Jacob's Pillow debuts, the return appearances of five companies, and work developed at Pillow Lab highlight Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival 2020, which begins June 24 and runs through Aug. 30 in the Ted Shawn and Doris Duke theaters. The season also will present new commissions, anniversary celebrations, Pillow-exclusive engagements, U.S. -

Margaret Barbieri Conservatory Summer Intensive

The Sarasota Ballet – Margaret Barbieri Conservatory Summer Intensive 27 June - 30 July 2016 Strengthen Technique - Learn Legendary Repertoire - Develop Artistry Faculty to include: - Iain Webb, Director of The Sarasota Ballet - Margaret Barbieri, Assistant Director of The Sarasota Ballet - Nancie Woods, Principal of The Conservatory - Renowned Guest Faculty to be announced at a later date The Pre-Professional Summer Intensive is a 5-week program (27 June - 30 July 2016) for ages 12 - 18. Younger students should have at least 3 years of serious ballet training and ladies must be en pointe. Information about tuition and housing will be available soon. Audition dates and locations are listed below. The Junior Summer Intensive is a 3-week program (11 July - 30 July 2016) for ages 9 - 11. Participation in all 3 weeks is mandatory and students should have at least 2 years of serious ballet training. There is no housing available for Junior Summer Intensive students. Auditions for the Junior Summer Intensive will be held in Sarasota only (see below); out of town students can send a video audition, with letter stating that their parent/guardian will be acccompanying them for the 3-week summer session. Audition Schedule There is a $25 audition fee. Please bring a headshot and 1st arabesque photo. Sarasota - 3 January 2016 Junior Summer Intensive Registration: 1:30 PM - 2:00 PM; Audition 2:00 PM - 3:15 PM Pre-Professional Summer Intensive Registration: 3:30 PM - 4:00 PM; Audition 4:00 PM - 5:30 PM The Sarasota Ballet - Margaret Barbieri Conservatory, -

The Shubert Foundation 2020 Grants

The Shubert Foundation 2020 Grants THEATRE About Face Theatre Chicago, IL $20,000 The Acting Company New York, NY 80,000 Actor's Express Atlanta, GA 30,000 The Actors' Gang Culver City, CA 45,000 Actor's Theatre of Charlotte Charlotte, NC 30,000 Actors Theatre of Louisville Louisville, KY 200,000 Adirondack Theatre Festival Glens Falls, NY 25,000 Adventure Theatre Glen Echo, MD 45,000 Alabama Shakespeare Festival Montgomery, AL 165,000 Alley Theatre Houston, TX 75,000 Alliance Theatre Company Atlanta, GA 220,000 American Blues Theater Chicago, IL 20,000 American Conservatory Theater San Francisco, CA 190,000 American Players Theatre Spring Green, WI 50,000 American Repertory Theatre Cambridge, MA 250,000 American Shakespeare Center Staunton, VA 30,000 American Stage Company St. Petersburg, FL 35,000 American Theater Group East Brunswick, NJ 15,000 Amphibian Stage Productions Fort Worth, TX 20,000 Antaeus Company Glendale, CA 15,000 Arden Theatre Company Philadelphia, PA 95,000 Arena Stage Washington, DC 325,000 Arizona Theatre Company Tucson, AZ 50,000 Arkansas Arts Center Children's Theatre Little Rock, AR 20,000 Ars Nova New York, NY 70,000 Artists Repertory Theatre Portland, OR 60,000 Arts Emerson Boston, MA 30,000 ArtsPower National Touring Theatre Cedar Grove, NJ 15,000 Asolo Repertory Theatre Sarasota, FL 65,000 Atlantic Theater Company New York, NY 200,000 Aurora Theatre Lawrenceville, GA 30,000 Aurora Theatre Company Berkeley, CA 40,000 Austin Playhouse Austin, TX 20,000 Azuka Theatre Philadelphia, PA 15,000 Barrington Stage Company -

Final January 2019 Newsletter 1-2-19

January 2019 Talking Pointes Jane Sheridan, Editor 508.367.4949 [email protected] From the Desk of the President Showcase Luncheon Richard March 941.343.7117 “Our Dancers—The Boys From [email protected] Brazil” Monday, February 11, 2019, Bird I’m excited for you to read about our winter party – Key Yacht Club, 11:30 AM Carnival at Mardi Gras – elsewhere in this newsletter. It will be at the Hyatt Boathouse on Carnival at Mardi Gras February 25th. This is a chance to have fun with other Monday, February 25, 2019, The Boathouse at the Hyatt Regency, Friends and dancers from the Company. It is also an 5:30 PM - 7:30 PM opportunity to help us raise funds for the Ballet. We need help in preparing a number of themed “Spring Fling” baskets that will be auctioned at the event. In the past, Sunday, March 31, 2019, The we’ve had French, Italian, wine, and chocolate Sarasota Garden Club, 4:00 PM – baskets, among others. Those who prepare baskets are 6:30 PM asked to spend no more than $50 in preparing them. However, you can add an unlimited number of gift Showcase Luncheon certificates or donations that will increase the appeal. Margaret Barbieri, Assistant Director, The Sarasota Ballet, If you would like to pitch in to support this effort, "Giselle: Setting An Iconic Work” please contact Phyllis Myers for information at Monday, April 15, 2019, Michael’s [email protected]. And, please come to On East, 11:30 AM the party. I am certain you will have fun! Were you able to see the performance of our dancers Pointe of Fact from the Studio Company and the Margaret Barbieri November was a record-setting Conservatory at the Opera House? Together with the month for the Friends of The Key Chorale, they took part in a program called Sarasota Ballet. -

Cynthia Roses-Thema

Cynthia Roses-Thema School of Film, Dance and Theatre [email protected] Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts 480-965-5337 Arizona State University Tempe, Arizona 85281 Academic Posts Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 2003-Present Principal Lecturer 2018-present Senior Lecturer 2007-2018 Faculty Adjunct 2003-2006 GateWay Community College 2008-2010 Faculty Adjunct 2008-2010 Education Ph.D. Rhetoric and Composition Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 2007 Dissertation: Reclaiming the Dancer: Embodied Perception in a Dance Performance Committee: Maureen Goggin, Arizona State University, Chair Sharon Crowley, Arizona State University Patricia Webb, Arizona State University Master of Fine Arts Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 2003 Thesis: Dance on the Inside: A Reflective Look at the Dance Student’s Perspective and Bodymind Awareness Committee: Mila Parrish, Chair Pamela Matt Melissa Rolnick Bachelor of Fine Arts summa cum laude University of Cincinnati, College Conservatory of Music, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1983 Certificates Advanced Certificate to teach English as a Second Language High Pass University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, 2010 Basic Certificate to teach English as a Second Language High Pass University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, 2009 Roses-Thema 2 Teaching Experience Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 2001-Present Graduate Courses Developed and/or Taught: Graduate Seminar Rhetorical Moves Contemporary Ballet Dance Kinesiology Undergraduate Courses Created, -

Professional Division Graduates, 1999-2014

Professional Division Graduates, 1999-2014 Name Company/College/University Year Heather Aagard Ballet Arizona; Joffrey Ballet 2001 Chelsea Adomaitis Pacific Northwest Ballet 2009 Tristan Alberda Milwaukee Ballet 2000 Maggie Alden Columbia University 2009 Kirsten Allman Louisville Ballet 2009 Garrett Anderson Hubbard Street Dance; Royal Ballet of Flanders; San Francisco Ballet 2001 Jessika Anspach Pacific Northwest Ballet 2004 Isaac Aoki Grand Rapids Ballet 2013 Emma Appel University of California, Berkeley 2011 Robbie-Jean Arbaczewski Central Pennsylvania Youth Ballet 2009 Jacquelyn Arcati Cherylyn Lavagnino Dance; Nevada Ballet; Columbia Univ. School of Law 2005 Thomas Baltrushunas Pennsylvania Ballet; Temple University 2002 Edward Barnes Pennsylvania Ballet 2008 Eli Barnes Cincinnati Ballet; Alberta Ballet 2011 Andrew Bartee Ballet BC; Pacific Northwest Ballet; Princess Grace Award Recipient 2008 Reid Bartelme Alberta Ballet; BalletMet; Current: Freelance fashion/costume designer 2001 Taisha Barton-Rowledge Ballet du Capitole, Toulouse, France; Carolina Ballet 2009 Alison Basford Boston Ballet; Pacific Northwest Ballet; Suzanne Farrell Ballet 2002 Marlowe Bassett Napoles Ballet Theatre; LINES Ballet; Metamorphosis (San Francisco) 2002 Reilley Bell Alberta Ballet 2007 Ezra Benjamin Cornish College of the Arts 2003 Christiana Bennett Ballet West (Principal Dancer) 1999 Laurel Benson Ballet West II 2014 Ian Bethany Ballet Austin 2008 Kelsey Bevington Nevada Ballet Theatre; Cincinnati Ballet II 2013 Perry Bevington Nevada Ballet Theatre, -

YAGP 2021 Brazil Scholarships&Acceptances RK 3.26

Scholarships and Acceptances Presented at YAGP 2021 Tampa Finals Alberta Ballet School, CANADA Summer Name Nationality School Constanza Medina Salcedo Mexico Ballet Clásico Aguascalientes Tsumugi Tomioka USA Hariyama Ballet Kelly Fong USA Li's Ballet Studio Peri Ingram USA Indiana Ballet Conservatory Audrey Williamson USA Ballet Center of Fort Worth Ava Thomas USA Marina Almayeva School of Classical Ballet Isabella Graves USA Huntington Academy of Dance Claire Buchi USA Peninsula School of Performing Arts Jayden Towers USA Fort Lauderdale Youth Ballet Annabelle Gourley USA The Ballet Clinic Savannah Rief USA Florida Schoolfor Dance Education Chloe Kinzler USA California Dance Academy Lyla Davey USA Huntington Academy of Dance Patricia Hohman USA West Point Ballet Alexa Pierce USA Pennsylvania Ballet Conservatory Nicholas Isabelli USA Emerald Ballet Academy Maria Nakai USA Hariyama Ballet Jaida Soleman USA Dance Center of San Antonio Nily Samara USA Bobbie's School of Performing Arts Charley Toscano USA North County Academy of Dance Leon Yusei Sai USA Southland Ballet Academy Noah Lehman USA Master Ballet Academy William Kinloch USA Ocean State Ballet Bella Dinglasan USA Southland Ballet Academy Sabrina Dorsey USA Master Ballet Academy Charlotte Bengfort USA Southland Ballet Academy Kate Deshler USA Jacqueline's School of Ballet Mia Anastasia Petkovic USA Ballet West Academy Lidiia Volkova USA Next Step Dance Performing Arts Julian Pecoraro USA University of North Carolina School of the Arts Luke Jones USA Ballet Center of Fort Worth Ashton Cook USA Elite Classical Coaching Olivia Newell USA Jacqueline's School of Ballet Ben Zusi USA Southold Dance Theater Joshua O'Connor USA Cary Ballet Conservatory Joshua Howell USA The Ballet Studio Tara McCally USA Feijoo Ballet School 1/13 Ballet School of the Basel Theater, SWITZERLAND Full Year Name Nationality School Sophie DeGraff USA WestMet Classical Training Laina Mae Kirkeide USA The Ballet Clinic Audrey Beukelman USA Denver Academy of Ballet Isabella McCool USA St. -

Celebra Ting 32 Years of Excellence, Quality & Joy!

BALLET ARTS OPEN DIVISION BALLET TUCSON & JOY! EXCELLENCE, QUALITY YEARS OF 32 CELEBRATING 2017 – 2018 Tucson Official School of Ballet Arizona School of Dance Training The Professional __________________________________________ www.balletartstucson.com (520) 623-3373 AZ 85716 TUCSON, TUCSON BLVD. 200 S. (Ballet Class Levels) (Ages are approximate and placement is based on ability.) PRE-BALLET: The Nutcracker BALLET 1: BALLET 2: Open c s auditions for Ballet Tucson performances of Phantom of the Opera and The Nutcracker are: BALLET 3: Saturday, August 19 & 26 and Saturday, September 9 Auditions for BT2 ( ) are: Friday, August 18 & 25 BALLET 4: Ballet Tucson American Ballet Theatre REGISTRATION FORM New York City Ballet Gus Giordano National Ballet School, Toronto Boston Ballet School of American Ballet Ballet West BALLET 5: Oregon Ballet Theatre Aspen/Santa Fe Ballet San Francisco Ballet The Kirov Academy Milwaukee Ballet Hartford Ballet Harid Conservatory Houston Ballet BALLET 6: Pacific Northwest Ballet Sarasota Ballet Cleveland Ballet Alvin Ailey Dance Theatre of Harlem Ballet Florida Pennsylvania Ballet Dayton Ballet BALLET 7 & 8: Disney Tokyo Ohio Ballet North Carolina School of the Arts Oakland Ballet Alabama Ballet Dutch National Ballet Louisville Ballet Washington Ballet Radio City Rockettes Joffrey Ballet PROFESSIONAL DIVISION TRAINEE TRACK (By audition/invitation only) TEEN/ADULT DIVISION Phantom of the Opera TEEN/ADULT BEGINNING BALLET/JAZZ: The Nutcracker TEEN/ADULT INTERMEDIATE & ADVANCED BALLET/JAZZ: All class placement is determined by the instructor and Artistic Director. JAZZ/TAP CLASS DESCRIPTIONS CLASS RATES RECOMMENDED STUDY FALL-WINTER-SPRING 2017 2018 Phantom of the Opera The Nutcracker non-refundable The Nutcracker Phantom of the Opera ENROLLMENT/TUITION POLICIES MONTHLY PAYMENT PLAN ACTUAL COST must CLASSES/MONTH TUITION PRE-BALLET PER CLASS Footprints at the Fox The Nutcracker THERE ARE NO EXCEPTIONS CONCERNING THESE POLICIES. -

Sunday, March 13, 2016 3:00 Pm Special to the Monitor

Posted: Sunday, March 13, 2016 3:00 pm Special to the Monitor Once again, dancers from the Deborah Case Dance Academy have received acceptance through an audition process to America’s most prestigious ballet programs. This summer, Jasmine Davila will be attending American Ballet Theatre Collegiate Program in NYC. She auditioned for and was accepted to attend Cincinnati Ballet Summer Intensive and Orland Ballet School Senior Intensive. Courtesy Photo Alyssa Zuniga received acceptance to San Francisco Conservatory of Dance, American Ballet Theatre in Austin, and Peter Sklar’s Beginnings Workshop in Hollywood. She will be attending the Beginnings Workshop this July. Elizabeth Garza, age 12, was accepted through audition for Houston Ballet’s summer intensive workshop. Garza was awarded partial scholarship to the six-week intensive workshop. Over the years, she has received numerous awards from Youth America Grand Prix in Dallas; was a finalist in World Ballet Competition in Orlando, Florida; and 1st place in Showstopper Regional Competition in Austin. Cielo Soto received scholarship to attend ballet intensives with NYC Ballet Performance track; Joffrey Ballet School in San Francisco, Miami, and Denver; Florence Intensive; Bolshoi Intensive; NY Broadway and LA Broadway. She will attend the Joffrey Ballet School this summer. The Joffrey Ballet School has been cultivating dancers for over 60 years. The prestigious school has a track record of producing professional dancers, choreographers, studio owners and professionals in the industry. Graduates are currently dancing with companies across the United States, including Boston Ballet, Miami City Ballet, Sarasota Ballet, Nevada Ballet, Complexions and Baller West. The Joffrey Ballet School creates dancers. -

Asolo Rep and the Sarasota Ballet Announce Completion of New Seating in the Harold and Esther Mertz Theatre in the FSU Center for the Performing Arts

New Seating Page 1 of 3 **FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE** September 24, 2019 Asolo Rep and The Sarasota Ballet Announce Completion of New Seating in the Harold and Esther Mertz Theatre in the FSU Center for the Performing Arts Photos of the new Mertz Theatre are available by visiting: https://asolorep.smugmug.com/Mertz-Theatre-2019/ (SARASOTA, September 24, 2019) — Asolo Repertory Theatre and The Sarasota Ballet proudly announce the completion of brand new seating in the Harold and Esther Mertz Theatre, the main performing space for Asolo Repertory Theatre and the home of The Sarasota Ballet. Located in the FSU Center for the Performing Arts, which is also home to the FSU/Asolo Conservatory for Actor Training, the exquisite Mertz Theatre is one of Sarasota's most populated and significant cultural venues. This installation was completed in August, with the comfortable new seating ready for Asolo Rep and The Sarasota Ballet's highly anticipated fall seasons. Capacity has increased from 503 to 535 seats, with most of the new seats added to the orchestra section of the theatre. Aisle lighting was also added for increased safety and visibility for patrons.The new layout also allows for an improvement in sight line clarity and an increase in ADA seating at a variety of price points. The seats, manufactured by Irwin Seating, are a replica of those in the historic New Amsterdam Theatre, the oldest operating theatre on Broadway, and reflect the style and aesthetic of the Mertz. The installation was funded by Florida State University and championed by Sally McRorie, the university's Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs. -

Final February 2020 Newsletter.Pages

February 2020 Talking Pointes Jane Sheridan, Editor 508.367.4949 [email protected] From the Desk of the Editor 2019 - 2020 Friends Events Jane Sheridan Showcase Luncheon Friends President Richard March asked me to take his normal Ricardo Graziano & Iain Webb, 10 spot in Talking Pointes this month. I’m honored to do so. Years with The Sarasota Ballet Monday, February 10, 2020, Michael’s It was so exciting to see Matthew Hart’s vision in John Ringling’s on East, 11:30 AM Circus Nutcracker – a first for me. The performances were outstanding. I attended the Saturday matinee whose audience was filled with children. What struck me was how quiet they were Showcase Luncheon as they sat spellbound by the magic on stage. It was quite Peter Schaufuss, Dancer & Director remarkable! Monday, March 16, 2020, Michael’s on East, 11:30 AM Next, of course, was the stunning Ballet Gala which was featured in January’s Brief Talking Pointes. This was an opportunity to showcase The Company, along with The Sarasota Ballet Studio Showcase Luncheon Company and Margaret Barbieri Conservatory students. Our Margaret Barbieri and “The Italian dancers excelled alongside internationally-known guest artists Job” including Marcelo Gomes, Diana Vishneva, Misa Monday, April 6, 2020, Bird Key Yacht Kuranaga, and Angelo Greco. The evening raised $600,000 Club, 11:30 AM for The Sarasota Ballet. The January Showcase Luncheon, discussed elsewhere in the newsletter, featured Jean Volpe interviewing Dominic Walsh. Let’s just say that it was a great introduction to I Napoletani, the final piece in the REDEFINED MOVEMENT program – a smorgasbord of delights that includes Ashton’s Les Rendezvous and The Company premiere of Paul Taylor’s Brandenburgs. -

May 2020 Newsletter

May 2020 Talking Pointes Jane Sheridan, Editor 508.367.4949 [email protected] From the Desk of the Editor From the Desk of the President Jane Sheridan Richard March 941.343.7117 [email protected] While this is not the Newsletter I As we deal with a crisis none of us expected to see in our had expected to write in May, we lifetime, I sincerely hope that you and your families are wanted to take this opportunity to healthy and staying safe. The coronavirus curtailed what had look back at the Season and to say been a wonderful Season for both The Sarasota Ballet and thank you to Richard March, as he finishes his two-year term as the Friends. Although our plans, like those of so many other President of the Friends. organizations, have been set aside, I am confident in the bright future for The Ballet and look forward to next Season We all owe him a debt of gratitude with great expectation. for what he has done for the Friends of The Sarasota Ballet. We were very disappointed that we had to cancel our March and April luncheons and thank those who donated back their You will get to read Richard tickets. As you may know, donations help us provide March’s thoughts as he finishes his two-year term as President. financial support to The Ballet. We had planned to present a gift of $20,000 to Director Iain Webb at the March A Peek Behind the Curtain offers luncheon. Since the event did not take place, we insight into the decision to cancel subsequently presented him with a check in this amount, the remainder of this Season, and along with an additional $1,000 for The Sarasota Ballet how The Ballet is supporting the Emergency Fund.