Muslims in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overlooking Sexism: How Diversity Structures Shape Women's

Overlooking Sexism: How Diversity Structures Shape Women’s Perceptions of Discrimination Laura M. Brady A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science University of Washington 2013 Committee: Cheryl Kaiser Janxin Leu Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Psychology ©Copyright 2013 Laura M. Brady Acknowledgements This research was conducted under the guidance of Cheryl Kaiser and Brenda Major and was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship awarded to Laura Brady and by National Science Foundation grants 1053732 & 1052886 awarded collaboratively to Brenda Major and Cheryl Kaiser. University of Washington Abstract Overlooking Sexism: How Diversity Structures Shape Women’s Perceptions of Discrimination Laura Michelle Brady Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Cheryl Kaiser, PhD Psychology Two experiments test the hypothesis that the mere presence (vs. absence) of diversity structures makes it more difficult for women to detect sexism. In Experiment 1, women who learned that a company required diversity training for managers thought the company was more procedurally just for women and was less likely to have discriminated against a female employee compared to women who learned the company offered general non-diversity related training for managers. Experiment 2 used a similar design, but also gave women evidence that the company had indeed discriminated against women in hiring practices. Again, compared to the control condition, women who learned that the company offered diversity training believed the company was more procedurally just for women, which led them to be less supportive of sexism related litigation against the company. To the extent that diversity structures legitimize the fairness of organizations, they may also make it more difficult for members of underrepresented groups to detect and remedy discrimination. -

Trends in Stroke Mortality in Greater London and South East England

Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 1997;51:121-126 121 Trends in stroke mortality in Greater London J Epidemiol Community Health: first published as 10.1136/jech.51.2.121 on 1 April 1997. Downloaded from and south east England-evidence for a cohort effect? Ravi Maheswaran, David P Strachan, Paul Elliott, Martin J Shipley Abstract to London to work in the domestic services Objective and setting - To examine time where they generally had a nutritious diet. A trends in stroke mortality in Greater Lon- study of proportional mortality from stroke don compared with the surrounding South suggested that persons born in London retained East Region of England. their lower risk of stroke when they moved Design - Age-cohort analysis based on elsewhere,3 but another study which used routine mortality data. standardised mortality ratios suggested the op- Subjects - Resident population aged 45 posite - people who moved to London acquired years or more. a lower risk of fatal stroke.4 Main outcome measure - Age specific While standardised mortality ratios for stroke stroke mortality rates, 1951-92. for all ages in Greater London are low, Health Main results - In 1951, stroke mortality of the Nation indicators for district health au- was lower in Greater London than the sur- thorities suggest that stroke mortality for rounding South East Region in all age Greater London relative to other areas may bands over 45. It has been declining in vary with age.5 both areas but the rate ofdecline has been The aim of this study was to examine time significantly slower in Greater London trends for stroke mortality in Greater London (p<0.0001). -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

The Trouble We''re In: Privilege, Power, and Difference

The Trouble Were In: Privilege, Power, and Difference Allan G. Johnson Thetroublearounddifferenceisreallyaboutprivilegeandpowertheexistenceofprivilege andthelopsideddistributionofpowerthatkeepsitgoing.Thetroubleisrootedinalegacyweall inherited,andwhilewerehere,itbelongstous.Itisntourfault.Itwasntcausedbysomethingwedid ordidntdo.Butnowitsallours,itsuptoustodecidehowweregoingtodealwithitbeforewe collectivelypassitalongtothegenerationsthatwillfollowours. Talkingaboutpowerandprivilegeisnteasy,whichiswhypeoplerarelydo.Thereasonforthis omissionseemstobeagreatfearofanythingthatmightmakewhitesormalesorheterosexuals uncomfortableorpitgroupsagainsteachother,1eventhoughgroupsarealreadypittedagainstone anotherbythestructuresofprivilegethatorganizesocietyasawhole.Thefearkeepspeoplefrom lookingatwhatsgoingonandmakesitimpossibletodoanythingabouttherealitythatliesdeeper down,sothattheycanmovetowardthekindofworldthatwouldbebetterforeveryone. Difference Is Not the Problem Ignoringprivilegekeepsusinastateofunreality,bypromotingtheillusionthedifferenceby itselfistheproblem.Insomeways,ofcourse,itcanbeaproblemwhenpeopletrytoworktogether acrossculturaldividesthatsetgroupsuptothinkanddothingstheirownway.Buthumanbeingshave beenovercomingsuchdividesforthousandsofyearsasamatterofroutine.Therealillusionconnected todifferenceisthepopularassumptionthatpeoplearenaturallyafraidofwhattheydontknowor understand.Thissupposedlymakesitinevitablethatyoullfearanddistrustpeoplewhoarentlikeyou and,inspiteofyourgoodintentions,youllfinditallbutimpossibletogetalongwiththem. -

MUSLIMS in BERLIN Muslims in Berlin

berlin-borito-10gerinc-uj:Layout 1 4/14/2010 5:39 PM Page 1 AT HOME IN EUROPE ★ MUSLIMS IN BERLIN Muslims in Berlin Whether citizens or migrants, native born or newly-arrived, Muslims are a growing and varied population that presents Europe with challenges and opportunities. The crucial tests facing Europe’s commitment to open society will be how it treats minorities such as Muslims and ensures equal rights for all in a climate of rapidly expanding diversity. The Open Society Institute’s At Home in Europe project is working to address these issues through monitoring and advocacy activities that examine the position of Muslims and other minorities in Europe. One of the project’s key efforts is this series of reports on Muslim communities in the 11 EU cities of Amsterdam, Antwerp, Berlin, Copenhagen, Hamburg, Leicester, London, Marseille, Paris, Rotterdam, and Stockholm. The reports aim to increase understanding of the needs and aspirations of diverse Muslim communities by examining how public policies in selected cities have helped or hindered the political, social, and economic participation of Muslims. By fostering new dialogue and policy initiatives between Muslim communities, local officials, and international policymakers, the At Home in Europe project seeks to improve the participation and inclusion of Muslims in the wider society while enabling them to preserve the cultural, linguistic, and religious practices that are important to their identities. OSI Muslims in Berlin At Home in Europe Project Open Society Institute New York – London – Budapest Publishing page OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE Október 6. Street 12. 400 West 59th Street H-1051 Budapest New York, NY 10019 Hungary USA OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATION 100 Cambridge Grove W6 0LE London UK TM a Copyright © 2010 Open Society Institute All rights reserved AT HOME IN EUROPE PROJECT ISBN Number: 978-1-936133-07-9 Website www.soros.org/initiatives/home Cover Photograph by Malte Jäger for the Open Society Institute Cover design by Ahlgrim Design Group Layout by Q.E.D. -

Ansari, Shaykh Murtada

ANIS — ANSARI 75 hardly surprising that the form ceased to be widely When Ansan met Mulla Ahmad Narak! (d. 1245/1829) cultivated after the end of the 19th century. in Kashan, he decided to remain there because he Bibliography: Critical accounts of Ams and his found Naraki's circle most congenial for learning. mardthi may be found in Muhammad Sadiq, History Narakl also found Ansari exceptionally knowledgeable, of Urdu literature, London 1964, 155-63; Abu '1-Layth saying that within his experience he had never met Siddiki, Lakhndu kd dabistdn-i shd'iri, Lahore 1955, any established mudjtahid as learned as Ansari, who which also contains examples from previous and was then ca. thirty years of age (Murtada al-Ansar!, subsequent marthiya poets. Ram Babu Saksena's Zjndigdnl va sjiakhsiyyat-i Shaykh-i Ansan kuddisa sirruh, History of Urdu literature, Allahabad 1927, in a gen- Ahwaz (sic) 1960/69). eral chapter on "Elegy and elegy writers" (123 ff.), 'in 1244/1828, Ansan left Kashan for Mashhad, contains a genealogical table of Anls's family and after a few months living there he went to Tehran. (p. 136), showing the poets in the family before In 1246/1830, he returned to Dizful, where he was and after him. widely recognised as a religious authority, despite the Among critical studies of Ams are Amir Ahmad, presence of other important culamd' in that town. It Tddgdr-i Ams, Lucknow 1924, and DjaTar cAll is said that Ansar! suddenly left Dizful secretly after Khan, Ams ki marthiya mgdn, Lucknow 1951. Shiblf sometime because he, as a religious-legal judge, was Nucman!'s Muwazana-yi-Ams-o-Dabir is still the stan- put under pressure to bring in a one-sided verdict in dard comparison of the two poets, though heav- a legal case. -

Obsessing About the Catholic Other: Religion and the Secularization Process in Gothic Literature Diane Hoeveler Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 1-1-2012 Obsessing about the Catholic Other: Religion and the Secularization Process in Gothic Literature Diane Hoeveler Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Obsessing about the Catholic Other: Religion and the Secularization Process in Gothic Literature," in L'obsession à l'œuvre: littérature, cinéma et société en Grande-Bretagne. Eds. Jean- François Baiollon and Paul Veyret. Bourdeaux: CLIMAS, 2012: 15-32. Publisher Link. © 2012 CLIMAS. Used with permission. Obsessing about the Catholic Other: Religion and the Secularization Process in Gothic Literature Perhaps it was totally predictable that the past year has seen both the publication of a major book by Lennard Davis entitled Obsession!, as well as a new two player board game called "Obsession" in which one player wins by moving his ten rings along numbered slots. Interest in obsession, it would seem, is everywhere in high and low cultures. For Davis, obsession is both a cultural manifestation of what modernity has wrought, and a psychoanalytical phenomenon: in fact, he defines it as a recurring thought whose content has become disconnected from its original significance causing the dominance of repetitive mental intrusions (Davis 6). Recent studies have revealed that there are five broad categories of obsession: dirt and contamination, aggression, the placing of inanimate objects in order, sex, and finally religion2 Another recent study, however, claims that obsessive thoughts generally center on three main themes: the aggressive, the sexual, or the blasphemous (qtd. Davis 9). It is that last category - the blasphemous - that I think emerges in British gothic literature of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, particularly as seen in the persistent anti-Catholicism that plays such a central role in so many of those works (Radcliffe's The italian, Lewis's The Monk, and Maturin's Melmoth the Wanderer being only the most obvious). -

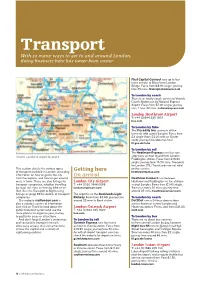

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

The Effect of Reproductive Compensation on Recessive Disorders Within Consanguineous Human Populations

Heredity (2002) 88, 474–479 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/hdy The effect of reproductive compensation on recessive disorders within consanguineous human populations ADJ Overall1,2, M Ahmad1 and RA Nichols1 1School of Biological Sciences, Queen Mary, University of London, UK We investigate the effects of consanguinity and population results show how reproductive compensation can effectively substructure on genetic health using the UK Asian popu- counteract the purging of deleterious alleles within con- lation as an example. We review and expand upon previous sanguineous populations. Whereas inbreeding does not treatments dealing with the deleterious effects of con- elevate the equilibrium frequency of affected individuals, sanguinity on recessive disorders and consider how other reproductive compensation does. We suggest this effect factors, such as population substructure, may be of equal must be built into interpretations of the incidence of genetic importance. For illustration, we quantify the relative risks of disease within populations such as the UK Asians. Infor- recessive lethal disorders by presenting some simple calcu- mation of this nature will benefit health care workers who lations that demonstrate the effect ‘reproductive compen- inform such communities. sation’ has on the maintenance of recessive alleles. The Heredity (2002) 88, 474–479. DOI: 10.1038/sj/hdy/6800090 Keywords: marriage; inbreeding; mortality; morbidity; genetic counselling Introduction whether reproductive compensation, at the level ident- ified by Koeslag and Schach (1984), can effectively The majority of the UK Asian population can trace their counteract the purging of deleterious alleles within con- origins to the Punjab region of India and Pakistan within sanguineous populations. -

The Hidden Cost of September 11 Liz Fekete

Racism: the hidden cost of September 11 Liz Fekete Racism: the hidden cost of September 11 Liz Fekete A special issue of the European Race Bulletin Globalisation has set up a monolithic economic system; September 11 threatens to engender a monolithic political culture. Together, they spell the end of civil society. – A. Sivanandan, Director, Institute of Race Relations Institute of Race Relations 2-6 Leeke Street, London WC1X 9HS Tel: 020 7837 0041 Fax: 020 7278 0623 Web: www.irr.org.uk Email: [email protected] Liz Fekete is head of European research at the Insitute of Race Relations where she edits the European Race Bulletin. It is published quarterly and available on subscription from the IRR (£10 for individuals, £25 for institutions). •••••• This report was compiled with the help of Saba Bahar, Jenny Bourne, Norberto Laguia Casaus, Barry Croft, Rhona Desmond, Imogen Forster, Haifa Hammami, Lotta Holmberg, Vincent Homolka, Mieke Hoppe, Fida Jeries, Simon Katzenellenbogen, Virginia MacFadyen, Nitole Rahman, Hazel Waters, and Chris Woodall. Special thanks to Tony Bunyan, Frances Webber and Statewatch. © Institute of Race Relations 2002 ISBN 085001 0632 Cover Image by David Drew Designed by Harmit Athwal Printed by Russell Press Ltd European Race Bulletin No. 40 Contents Introduction 1 1. The EU approach to combating terrorism 2 2. Removing refugee protection 6 3. Racism and the security state 10 4. Popular racism: one culture, one civilisation 16 References 22 European Race Bulletin No. 40 Introduction ollowing the events of September 11, it became commonplace to say that the world would Fnever be the same again. -

Churches of Marylebone (Pdf)

The Churches of Marylebone The Parish Church: Marylebone owes its name to its parish church. Although originally dedicated to St John the Baptist, the Parish Church has, since 1400, been dedicated to The Blessed Virgin Mary. A parish church is recorded by the 12th century and this building was situated on, what is today, Oxford Street. The parish church has always been the parish church of the Manor of Tyburn and when the parish church was moved to a position opposite the old manor house (at the top of what is now Marylebone High Street) St Mary by the Ty Bourne got shortened to Mary-le bone and then to Marylebone. The present parish church building dates from 1817 and was designed by the architect Thomas Hardwicke. Now, just off the High Street, there are three churches. They are from different Christian traditions, with different patterns of worship and different emphases in the faith, but they work together. They are one in following Jesus and his way of love. The Parish Church and Hinde Street Methodist Church signed a formal Covenant to work together in 2007. They have active links with other faiths: with the West London Synagogue, the London Central Mosque and the Buddhist Temple on Margaret Street. The parish of St Marylebone once encompassed an enormous geographical area stretching from Oxford Street in the south to Maida Vale in the north and Edgware Road in the west to the boundary with Camden in the east: the old manors of Tyburn and Lillestone. Today, this area is served by many other parish churches, all carved out of the historic parish of St Marylebone. -

A Study on the Theory of God's Science of Maturidi School Cunping

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 328 4th International Conference on Humanities Science and Society Development (ICHSSD 2019) A Study On the Theory of God's Science of Maturidi School Cunping Yun School of Foreign Language, Northwest Minzu University, Lanzhou, Gansu, China, 730050 [email protected] Keywords: Islamic theology, The science of God, Maturidi school Abstract: Maturidi school is one of the two pillars of Sunni sect in Islamic theology. In the heated debate on Islamic dogmatics, Maturidi school unswervingly protected the authority of the Book and the reason and became the one of the founders of the Sunni theology. Maturidi school successfully applied dialectical principles to ensure the supremacy of the Scriptures and at the same time upheld the role of the reason. They maintained a more rational and tolerant attitude toward many issues, and it is called "Moderatism"by the Sunni scholars. The thought of Maturidi school spread all over Central Asian countries, Afghanistan, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Rome, Persian, Turkey, Egypt and China ,etc.. In today's globalized and diversified international situation, it is of great significance to enhance the study of Maturidi school's theological thought, especially it's theory of God's Science in order to promote ideological and cultural exchanges between our country and Muslim world and to enhance the mutual understanding. 1. Introduction Muslims began to argue about the fundamental principles of Islamic belief after the Prophet passed away. And some muslim scholars even touched upon the theological questions like the essence, attributes of Allah and the relationship between human and the universe in the influence of foreign cultures of Greece, Persia and Syria, and then "Ilm El-Kalam"(Islamic theology) came into being.