Criminal Procedural Agreements in China and England and Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reconciling Ireland's Bail Laws with Traditional Irish Constitutional Values

Reconciling Ireland's Bail Laws with Traditional Irish Constitutional Values Kate Doran Thesis Offered for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Law Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences University of Limerick Supervisor: Prof. Paul McCutcheon Submitted to the University of Limerick, November 2014 Abstract Title: Reconciling Ireland’s Bail Laws with Traditional Irish Constitutional Values Author: Kate Doran Bail is a device which provides for the pre-trial release of a criminal defendant after security has been taken for the defendant’s future appearance at trial. Ireland has traditionally adopted a liberal approach to bail. For example, in The People (Attorney General) v O’Callaghan (1966), the Supreme Court declared that the sole purpose of bail was to secure the attendance of the accused at trial and that the refusal of bail on preventative detention grounds amounted to a denial of the presumption of innocence. Accordingly, it would be unconstitutional to deny bail to an accused person as a means of preventing him from committing further offences while awaiting trial. This purist approach to the right to bail came under severe pressure in the mid-1990s from police, prosecutorial and political forces which, in turn, was a response to a media generated panic over the perceived increase over the threat posed by organised crime and an associated growth in ‘bail banditry’. A constitutional amendment effectively neutralising the effects of the O'Callaghan jurisprudence was adopted in 1996. This was swiftly followed by the Bail Act 1997 which introduced the concept of preventative detention (in the bail context) into Irish law. -

A Review of the United Kingdom's

A REVIEW OF THE UNITED KINGDOM’S EXTRADITION ARRANGEMENTS (Following Written Ministerial Statement by the Secretary of State for the Home Department of 8 September 2010) Presented to the Home Secretary on 30 September 2011 This report is also available online at http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/ ~ 2 ~ The Rt Hon Sir Scott Baker was called to the Bar in 1961, and practised in a range of legal areas, including criminal law and professional negligence. He became a Recorder in 1976 and was appointed as a High Court judge in 1988. In 1999, he presided over the trial of Great Western Trains following the Southall rail crash in 1997 and in the same year was the judge who tried Jonathan Aitken. He was the lead judge of the Administrative Court between 2000 and 2002 when he was appointed a Lord Justice of Appeal, presiding over the inquests into the deaths of Princess Diana and Dodi Al Fayed. He also sat regularly in the Divisional Court hearing appeals and judicial reviews in extradition cases. He retired in 2010 and is currently a Surveillance Commissioner, a member of the Bermuda Court of Appeal and a member of the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority. David Perry QC is a barrister and joint head of chambers at 6 King’s Bench Walk, Temple. From 1991 to 1997, Mr Perry was one of the Standing Counsel to the Department of Trade and Industry. From 1997 to 2001, he was Junior Treasury Counsel to the Crown at the Central Criminal Court and Senior Treasury Counsel from 2001 until 2006, when he took silk. -

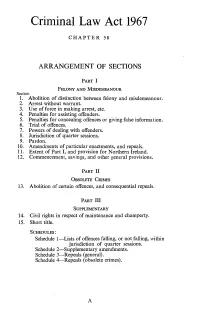

Arrangement of Sections

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART 11 OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES: Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH n , 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] E IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and BTemporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are J\b<?liti?n of hereby abolished. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Criminal Law Act 1826

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1826. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1826 1826 CHAPTER 64 7 Geo 4 An Act for improving the Administration of Criminal Justice in England. [26th May 1826] Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Short title given by Short Titles Act 1896 (c. 14) C2 Preamble omitted under authority of Statute Law Revision Act 1890 (c. 33) 1 . F1 Textual Amendments F1 S. 1 repealed by Statute Law Revision Act 1950 (c. 6), Sch. 1 2, 3. F2 Textual Amendments F2 Ss. 2, 3 repealed by Indictable Offences Act 1848 (c. 42), s. 34 4 . F3 Textual Amendments F3 S. 4 repealed by Coroners Act 1887 (c. 71), Sch. 3 2 Criminal Law Act 1826 (c. 64) Document Generated: 2021-07-21 Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1826. (See end of Document for details) 5, 6. F4 Textual Amendments F4 Ss. 5, 6 repealed by Statute Law Revision Act 1950 (c. 6), Sch. 1 7, 8. F5 Textual Amendments F5 Ss. 7, 8 repealed by Statute Law Revision Act 1873 (c. 91) 9—11. F6 Textual Amendments F6 Ss. 9-11 repealed by The Act 24 and 25 Vict. c. 95, Sch. 12, 13. F7 Textual Amendments F7 Ss. 12, 13 repealed by Courts Act 1971 (c. 23), Sch. 11 Pt. IV 14— . F8 16. Textual Amendments F8 Ss. 14-16 repealed by Indictments Act 1915 (c. 90), Sch. 2 17 . F9 Textual Amendments F9 S. -

Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are outstanding changes not yet made by the legislation.gov.uk editorial team to Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005. Any changes that have already been made by the team appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 2005 CHAPTER 15 An Act to provide for the establishment and functions of the Serious Organised Crime Agency; to make provision about investigations, prosecutions, offenders and witnesses in criminal proceedings and the protection of persons involved in investigations or proceedings; to provide for the implementation of certain international obligations relating to criminal matters; to amend the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002; to make further provision for combatting crime and disorder, including new provision about powers of arrest and search warrants and about parental compensation orders; to make further provision about the police and policing and persons supporting the police; to make provision for protecting certain organisations from interference with their activities; to make provision about criminal records; to provide for the Private Security Industry Act 2001 to extend to Scotland; and for connected purposes. [7th April 2005] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— F1 PART 1 THE SERIOUS ORGANISED CRIME AGENCY Textual Amendments F1 Pt. 1 omitted (7.10.2013) by virtue of Crime and Courts Act 2013 (c. -

Statute Law Revision: Sixteenth Report Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill

LAW COMMISSION SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION STATUTE LAW REVISION: SIXTEENTH REPORT DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL CONTENTS Paragraph Page REPORT 1 APPENDIX 1: DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL 2 APPENDIX 2: EXPLANATORY NOTE ON THE DRAFT BILL 46 Clauses 1 – 3 46 Schedule 1: Repeals 47 PART I: Administration of Justice 47 Group 1 - Sheriffs 1.1 47 Group 2 - General Repeals 1.4 48 PART II: Ecclesiastical Law 51 Group 1 - Ecclesiastical Leases 2.1 51 Group 2 - Tithe Acts 2.6 53 PART III: Education 57 Group 1 - Public Schools 3.1 57 Group 2 - Universities 3.2 57 PART IV: Finance 60 Group 1 - Colonial Stock 4.1 60 Group 2 - Land Commission 4.4 60 Group 3 - Development of Tourism 4.6 61 Group 4 - Loan Societies 4.7 62 Group 5 - General Repeals 4.9 62 PART V: Hereford and Worcester 65 Statutory Undertaking Provisions 5.8 68 Protective Provisions 5.15 71 Bridges 5.16 72 Miscellaneous Provisions 5.24 75 PART VI: Inclosure Acts 77 iii Paragraph Page PART VII: Scottish Local Acts 83 Group 1 - Aid to the Poor, Charities and Private Pensions 7.7 84 Group 2 - Dog Wardens 7.9 85 Group 3 - Education 7.12 86 Group 4 - Insurance Companies 7.13 86 Group 5 - Local Authority Finance 7.14 87 Group 6 - Order Confirmation Acts 7.19 89 Group 7 - Oyster and Mussel Fisheries 7.22 90 Group 8 - Other Repeals 7.23 90 PART VIII: Slave Trade Acts 92 PART IX: Statutes 102 Group 1 - Statute Law Revision Acts 9.1 102 Group 2 - Statute Law (Repeals) Acts 9.6 103 PART X: Miscellaneous 106 Group 1 - Stannaries 10.1 106 Group 2 - Sea Fish 10.3 106 Group 3 - Sewers Support 10.4 107 Group 4 - Agricultural Research 10.5 108 Group 5 - General Repeals 10.6 108 Schedule 2: Consequential and connected provisions 115 APPENDIX 3: CONSULTEES ON REPEAL OF LEGISLATION 117 PROPOSED IN SCHEDULE 1, PART V iv THE LAW COMMISSION AND THE SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION STATUTE LAW REVISION: SIXTEENTH REPORT Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill To the Right Honourable the Lord Irvine of Lairg, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, and the Right Honourable the Lord Hardie, QC, Her Majesty’s Advocate 1. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART II OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES : Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH II 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are Abolition of abolished. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by [F3section 33 of the Magistrates’Courts Act 1980)]] and to attempts to committ any 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Jurisdiction Over Offences of Fraud and Dishonesty with a Foreign Element

The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 180) CRIMINAL LAW JURISDICTION OVER OFFENCES OF FRAUD AND DISHONESTY WITH A FOREIGN ELEMENT Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 27 April 1989 LONDON HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE E6.60 net 318 The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are- The Honourable Mr Justice Beldam, Chairman Mr Trevor M. Aldridge Mr Richard Buxton, Q.C. Professor Brenda Hoggett, Q.C. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Collon and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London,.WClN 2BQ. 11 JURISDICTION OVER OFFENCES OF FRAUD AND DISHONESTY WITH A FOREIGN ELEMENT CONTENTS Paragraphs Page PART I-INTRODUCTION 1.1-1.9 1 A. The background to the report 1.1-1.3 1 B. The basic principles and the structure of the report 1.4-1.9 2 PART 11-SUBSTANTIVE OFFENCES 2.1-2.32 4 A. Outline of the present law 2.1-2.6 4 B. Criticisms of the present law 2.7-2.13 5 C. The position in some other common law states 2.14-2.19 7 1. The Model Penal Code of the American Law Institute 2.14 7 2. Canada 2.15 8 3. Australia 2.1 6-2.18 8 (a) Queensland and Western Australia 2.17 8 (b) Tasmania 2.18 9 4. -

Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005

Changes to legislation: There are outstanding changes not yet made by the legislation.gov.uk editorial team to Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005. Any changes that have already been made by the team appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 CHAPTER 15 SERIOUS ORGANISED CRIME AND POLICE ACT 2005 PART 1 THE SERIOUS ORGANISED CRIME AGENCY CHAPTER 1 SOCA: ESTABLISHMENT AND ACTIVITIES Establishment of SOCA 1 Establishment of Serious Organised Crime Agency Functions 2 Functions of SOCA as to serious organised crime 2A Functions of SOCA as to the recovery of assets 3 Functions of SOCA as to information relating to crime 4 Exercise of functions: general considerations General powers 5 SOCA's general powers Annual plans and reports 6 Annual plans 7 Annual reports ii Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 (c. 15) Document Generated: 2021-09-04 Changes to legislation: There are outstanding changes not yet made by the legislation.gov.uk editorial team to Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005. Any changes that have already been made by the team appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Central supervision and direction 8 General duty of Secretary of State and Scottish Ministers 8A General duty of the Department of Justice in Northern Ireland 9 Strategic priorities 10 Codes of practice 11 Reports to Secretary of State 12 Power to direct -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART IFELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1)All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2)Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12Arrest without warrant. (1)The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by [F3section 33 of the Magistrates’Courts Act 1980)]] and to attempts to committ any such offence; and in this Act, including any amendment made by this Act in any other enactment, ―arrestable offence‖ means any such offence or attempt.