History in Practice Ritual Deposition at La Venta Complex A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chalcatzingo:Abrief Introduction Special DAVID C

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume IX, No. 1, Summer 2008 Chalcatzingo:ABrief Introduction Special DAVID C. GROVE Chalcatzingo Issue University of Florida containing: In 1934 archaeologist Eulalia Guzmán trav- bas-relief carvings. The largest of them Chalcatzingo: A eled to the remote hamlet of Chalcatzingo (Monument 1), nicknamed “El Rey” by Brief Introduction near Jonacatepec in the Amatzinac valley the villagers, depicts a personage seated of eastern Morelos state to investigate re- in a cave-like niche above which are rain by ports of “stones with reliefs.” The village clouds and falling raindrops (Guzmán David Grove sits near two conjoined granodiorite hills 1934:Fig. 3) (Figure 2). In addition, in a PAGES 1-7 or cerros—the Cerro Delgado and the larg- small barranca that cuts through the site er Cerro Chalcatzingo (also known as the Guzmán was shown a unique three di- • Cerro de la Cantera)—that jut out starkly mensional sculpture—a “mutilated stat- against the relatively flat landscape of the ue” of a seated personage, minus its head. Chalcatzingo valley (Figure 1). The archaeological site Guzmán also found pot sherds dating to Monument 34: A that Guzmán viewed is situated just at both the “Archaic” (Preclassic or Forma- Formative Period the base of those cerros where they meet tive) and “Teotihuacan” (Classic) periods, “Southern Style” to form a V-shaped cleft. The ancient oc- leaving her uncertain as to the date of the Stela in the Central cupation extended across a series of ter- carvings (Grove 1987c:1). Mexican Highlands races below the twin cerros. -

Were-Jaguars and Crocodilians: a Need to Redefine

Takkou-Neofytou, R 2014 Were-Jaguars and Crocodilians: A Need to Redefine. pia Papers from the Institute of Archaeology, 24(1): 25, pp. 1-12, DOI: http:// dx.doi.org/10.5334/pia.472 GENERAL Were-Jaguars and Crocodilians: A Need to Redefine Richard Takkou-Neofytou* The general consensus amongst scholars is that anthropomorphic and zoomorphic Formative art, usually associated with the Olmecs but extending to post-Columbian civilisations, are depictions of humans and/or jaguars known as were-jaguars (De La Fuente 2000: 258). More recently, there has been discussion concerning what is actually being depicted through this Mesoamerican art form. In this paper, I will argue that the art form is much more complex than first anticipated with motifs of different deities amalgamated into one depiction, thereby extolling ceremonial influence to other animals worshipped in a religion based on animism, whilst also looking critically at some anthropomorphic images of the jaguar. Introduction art under the umbrella of the jaguar. Colin Upon entering the Mexico gallery at the McEwan, the former curator of this gallery, British Museum, it occurred to me that the writes (McEwan 2009: 136): Museum was endorsing a particular view of Olmec art history; a view that is quite conten- This massive ceremonial axe (celt) tious since the issue surrounding the genre combines characteristics of the cai- of the type of art in question has not yet been man and the jaguar, the most pow- settled. Of course, I refer to the ‘were-jaguar’ erful predators inhabiting the rivers and its feline components (see figures 1 and and forests of the tropical lowlands. -

A 3D Model of Complex A, La Venta, Mexico

Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 1 (2014) 72–81 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/daach A 3d model of Complex A, La Venta, Mexico Susan D. Gillespie a,n, Michael Volk b a Department of Anthropology, University of Florida, P.O. Box 117305, Gainesville, FL 32611-7305 USA b Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Florida, P.O. Box 115704, Gainesville, FL 32611-5704 USA article info abstract Article history: La Venta was a large regional center located near the Gulf coast in Tabasco, Mexico. From ca. 800–400 BC Received 21 September 2013 it was the major Olmec capital in Mesoamerica. Despite its significance La Venta has received little Received in revised form archeological attention. The clay structures of its ritual precinct, Complex A, excavated in the 1940s–50s, 14 April 2014 were subsequently destroyed. Unfortunately, the published reports on those excavations are inadequate, Accepted 27 June 2014 with misleading archeological drawings. In order to obtain a more precise and comprehensive under- Available online 5 July 2014 standing of La Venta the original excavation records were consulted, and field drawings and maps were Keywords: digitized to create more accurate 2d images as well as a 3d model of Complex A. This article summarizes La Venta the process of digitizing the archival records and the interpretive benefits from utilizing 3d visualizations Olmec of the site. Recounting the process may inform similar projects dependent on archival records when field Archival archeology mapping or excavation are no longer possible. -

Informe Del Proyecto Arqueológico Ceibal-Petexbatun La Temporada 2011

INFORME DEL PROYECTO ARQUEOLÓGICO CEIBAL-PETEXBATUN LA TEMPORADA 2011 Editado por Victor Castillo Aguilar y Takeshi Inomata Directores Takeshi Inomata y Victor Castillo Aguilar Informe entregado al Instituto de Antropología e Historia 2011 Agradecimientos El Proyecto Arqueológico Ceibal-Petexbatun desea manifestar su agradecimiento a las personas e instituciones que apoyaron la realización de la Temporada 2011. Se agradece al Maestro Erick Ponciano, Director del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural del Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes, a la Licenciada Mónica Urquizú, Directora Técnica del Instituto de Antropología e Historia y a la Licenciada Griselda Pérez Robles, Jefa del Departamento de Monumentos Prehispánicos y Coloniales por el apoyo institucional para la ejecución del proyecto. A la Licenciada Ana Lucía Arroyave y la Licenciada Elisa Mencos, supervisoras del proyecto, al Sr. Julio López, Inspector de Monumentos de la zona y demás trabajadores del Instituto de Antropología e Historia pos su apoyo y colaboración. El Proyecto Arqueológico Ceibal-Petexbatun fue financiado por la Universidad de Ibaraki, fondo que es otorgado por el Ministerio de Educación, Cultura, Deportes, Ciencia y Tecnología de Japón. CONTENIDO Agradecimientos PARTE I: INTRODUCCIÓN 1. Introducción a la temporada de 2010 1 Takeshi Inomata y Victor Castillo Aguilar PARTE II: INVESTIGACIONES EN LA CORTE ESTE 2. Excavaciones enfrente de la Estructura A-15: Operación 201B 7 Daniela Triadan 3. Excavaciones en la Estructura A-14: Operación 201C 23 Giovanni González y Daniela Triadan 4. Excavaciones detrás de la Corte Este: Operación 201D 30 Jessica MacLellan 5. Excavaciones en la fachada oeste de la Estructura A-14: Operación 201E 37 María Belén Méndez Bauer 6. -

2. Background of the 1976 UCB Project During the Summer of 1975 We Discussed the Feasibility and Profitability of Detailed Explorations at Abaj Takalik

85 ABAJ TAKALIK 1976: EXPLORATORY INVESTIGATIONS by J.A. Graham, R.F. Heizer, andE.M. Shook 1. Preface In February, 1976, in the course of a preliminary exploration of the archaeological site of Abaj Takalik, Department of Retalhuleu, southwestern Guatemala, for the purpose of evaluating its potential for more intensive investigations, a number of very important discoveries were made. While these finds serve to justify more thorough investigation of the site in the near future, an interim and preliminary report should be of interest to colleagues. Since fuller investigations will greatly expand our present information on the site, the present report will not attempt to present all data resulting from our 1976 preliminary investigations nor to undertake detailed analysis of the data collected which are still in the process of study. Monument terminology for sculptures previously reported from the site follows that of Miles (1965: 246) and as expanded,with a single exception, by Parsons (1972: 203). In a later report we will provide a fuller table of terminology including early references to these and other monuments from sources not utilized by Miles and Parsons. The earlier practice of referring to sections of the site by names of the various modern fincas which now divide up the ruins, as well as references to the site as Colomba, have created considerable confusion and some misunderstandings; to correct this problem, Miles (1966: 246) christened the ruins "Abaj Takalik" (her translation of "piedra parada" into Quiche), a convenient designation now generally adopted. In the present report we have provided descriptions of only a sampling of the many new or unpublished sculptured and plain monuments from the site; further work will expand our data on these and other monuments and will further provide a better photographic record than we were able to obtain with the limited time and resources available to us. -

California State University, Northridge the Were

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THE WERE-JAGUAR MOTIF AND THE OLMEC CHIEFDOM A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the .requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology by Bryn Marie Barabas January 1985 0 • The Thesis of Bryn Marie Barabas is approved: Susan Kenagy Dav~ Hayanbj f{_ Robert Ravicz, Chairma~ California State University, Northridge ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to gratefully acknowledge all of the help and guidance provided by my committee members, Susan Kenagy, David Hayano, Robert Ravicz, and my second ·chair Carol Mackey, without whom this thesis wo~ld not have been possible. I also extend thanks to Gregory Truex, Charles Bearchell, and Ralph Vicero for coming through in the end. Thanks Mom and Pops for your patient understanding and encouragement. And finally, multiple thank yous to all of those special people, particularly R. J., for seeing me through with my elusive were-jaguar dream. iii TABLE ·oF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • • • • • • • • • • • • iii LIST OF FIGURES • • • • • • • • • • • • v ABSTRACT • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • vi Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • 1 2 DEFINITIONS • • • • • • • • • • 5 Summary • • • • • • • • • • 14 3 BACKGROUND • • • • • • • • • • 16 Summary • • • • • • • • • • 36 4 THE WERE-JAGUAR • • • • • • • • • 38 Summary • • • • • • • • • • 71 5 SAN LORENZO • • • • • • • • • • 73 Summary • • • .. • • • • • • 86 6 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS • _. • • • • 89 Conclusions • • • • • • • • • 93 NOTES • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 97 FIGURES • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 99 REFERENCES • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 117 APPENDIX • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 130 iv LIST OF FIGURES figure page 1 The Olmec Area (Weaver 1981:63). • • • • • • 100 2 Chronology (Coe 1970; Tolstoy 1978; Weaver 1981) • 101 3 Olmec Central Places (Bernal 1969; Bove 1976:129). 102 4 Celts or Ceremonial Axes (Covarrubias 1946:30). • 103 5 Evolution of Mesoamerican Rain Gods (Covarrubias 1946:27) ~ • • • • • • • • • 104 6 R{o Chiquita Monument 1 (Joralemon 1976:31). -

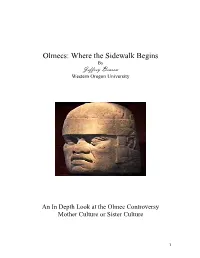

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins by Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. The data collected links the Olmecs to other cultures in several areas such as writing, pottery and art. With this new found data two main theories have evolved. The first is that the Olmecs were the mother culture. This theory states that writing, the calendar and types of art originated under Olmec rule and later were spread to future generational tribes of Mesoamerica. The second main theory proposes that the Olmecs were one of many contemporary cultures all which acted sister cultures. The thought is that it was not the Olmecs who were the first to introduce writing or the calendar to Mesoamerica but that various indigenous surrounding tribes influenced and helped establish forms of writing, a calendar system and common types of art. -

Stone Monuments of the Rio Chiquito, Veracruz, Mexico

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology BuUetin 157 Anthropological Papers, No. 43 Stone Monuments of the Rio Chiquito, Veracruz, Mexico By MATTHEW W. STIRLING CONTENTS PAGB Introduction 5 Rio Chiquito 7 Description of monuments 8 Monument 1 8 Monument 2 8 Miscellaneous stone 8 San Lorenzo 8 Description of monuments 9 Monument 1 9 Monument 2 10 Monument 3 H Monument 4 11 Monument 5 12 Monument 6 13 Monument 7 13 Monument 8 13 Monument 9 13 Monument 10 14 Monument 11 14 Monument 12 15 Monument 13 15 Monument 14 15 Monument 15 16 Miscellaneous stones 16 Potrero Nuevo 17 Description of monuments 18 Monument 1 18 Monument 2 19 Monument 3 19 Stone snake.. 20 General discussion 20 Literature cited 23 8 ILLUSTEATIONS PLATES FOLLOWING PAGE 1. Clearing a monument at San Lorenzo. Type of jungle growth that covered the site 24 2. Rio Chiquito. Monument 1, 24 3. Rio Chiquito: a, c, Monument 2; h, stone vessels 24 4. Rfo Chiquito. Granite columns 24 5. San Lorenzo. Monument 1 24 6. San Lorenzo. Monument 1 24 7. San Lorenzo. Monument 2 24 8. San Lorenzo. Monuments 24 9. San Lorenzo. Monument 4 24 10. San Lorenzo. Monument 4 24 11. San Lorenzo: a, Monument 4; h, Monument 13 24 12. San Lorenzo. Monuments 24 13. San Lorenzo. Monument 5 24 14. San Lorenzo. Monument 6 24 15. San Lorenzo: a, Monuments; h, Monument 10 24 16. San Lorenzo: a, Monument 11; 6, Monument 12 24 17. San Lorenzo: a, Monument 7; h, Monument 9 24 18. -

Informe Del Proyecto Arqueológico Usumacinta Medio La Temporada

Informe del Proyecto Arqueológico Usumacinta Medio: La Temporada de 2017 Item Type Report; text Authors Inomata, Takeshi; Triadan, Daniela; Liendo, Rodrigo Citation Liendo, Rodrigo, Takeshi Inomata, and Daniela Triadan (editors) Informe del Proyecto Arqueológico Usumacinta Medio: La Temporada de 2017. Report presented to the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Publisher The University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Rights Copyright © The Authors. All rights reserved. Download date 30/09/2021 13:59:04 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/636878 Informe del Proyecto Arqueológico Usumacinta Medio La Temporada de 2017 Presentado al Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia Por Dr. Rodrigo Liendo Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas UNAM Dr. Takeshi Inomata Dra. Daniela Triadan Escuela de Antropología Universidad de Arizona [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1 Contenidos Resumen ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Agradecimientos ............................................................................................................................ 5 1. Introducción .............................................................................................................................. 6 Objetivos .................................................................................................................................................. -

Una Aproximación a Los Relieves De Chalcatzingo: El Escaneo Láser 3D

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections Faculty and Staff Publications Tampa Library 1-1-2015 Una aproximacioń a los relieves de Chalcatzingo: el escaneo laseŕ 3D Mario Córdova Tello Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico Carolina Meza Rodríguez Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico Omar Espinosa Severino Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico Travis F. Doering University of South Florida Lori D. Collins University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/dhhc_facpub Scholar Commons Citation Tello, Mario Córdova; Rodríguez, Carolina Meza; Severino, Omar Espinosa; Doering, Travis F.; and Collins, Lori D., "Una aproximacioń a los relieves de Chalcatzingo: el escaneo laseŕ 3D" (2015). Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections Faculty and Staff Publications. 1. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/dhhc_facpub/1 This Technical Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Tampa Library at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Una aproximación a los relieves de Chalcatzingo: el escaneo láser 3D. MARIO CÓRDOVA TELLO1 CAROLINA MEZA RODRÍGUEZ2 OMAR ESPINOSA SEVERINO3 TRAVIS F. DOERING4 LORI D. COLLINS5 La arqueología es una disciplina científica cuyas inferencias giran entorno a la memoria colectiva representada en la materialidad de las sociedades; su objetivo principal es reconocer lo objetos usados en la antigüedad e identificar en ellos las cargas simbólicas y las construcciones sociales que los hacían útiles, necesarios e indispensables. Sin embargo, la arqueología se enfrenta a varios retos para alcanzar dicho objetivo: desde la obtención adecuada de los datos para las inferencias, hasta el tipo de interpretaciones que resultan con dichas deducciones. -

La Historia Arquitectónica Del Complejo "A" De La Venta: Una Reconstrucción Basada En Los Registros De Campo De 1955

FAMSI © 2010: Susan D. Gillespie La historia arquitectónica del Complejo "A" de La Venta: una reconstrucción basada en los registros de campo de 1955 Año de Investigación: 2007 Cultura: Olmeca Cronología: Preclásico Medio (ca. 900-500 a.C.) Ubicación: Tabasco, México Sitio: La Venta Tabla de Contentidos Resumen Abstract Introducción: Antecedentes del Proyecto Antecedentes del Problema de Investigación La Venta La arquitectura del Complejo "A" Las fases constructivas del Complejo "A" Problemas con los mapas y dibujos del Complejo "A" El mapa de 1955 del Complejo "A" El mapa de La Venta hecho en 1968 Los dibujos de perfiles Resumen Los registros de campo de 1955 Los papeles de Robert F. Heizer Datos de elevación La digitalización de la información del Complejo "A" Los mapas fase por fase Conclusiones Agradecimientos Lista de Figuras Lista de Cuadros Referencias Citadas Entregado el 5 de febrero del 2008 por: Susan D. Gillespie Department of Anthropology University of Florida [email protected] Resumen El Complejo A, la zona ceremonial del sitio Formativo Medio olmeca de La Venta, Tabasco, se excavó en 1955 en un proyecto dirigido por Philip Drucker y Robert Heizer. Desgraciadamente, la arquitectura de la superficie del Complejo A fue destruido en 1956, tanto que los arqueólogos debían que fiarse de los 1955 mapas, dibujos de perfiles, y las descripciones de las excavaciones, que se publicó en 1959. Sin embargo, hay muchos defectos reconocidos en la publicación de 1959. El objetivo de este proyecto debía obtener información adicional con respecto a las 1955 excavaciones consultando los mapas de campo y registros en los Archivos Antropológicos Nacionales (Institución Smithsonian) en Suitland, Maryland. -

Chalcatzingo Monument 34: a Formative Period “Southern Style” Stela in the Central Mexican Highlands Susan D

Chalcatzingo Monument 34: A Formative Period “Southern Style” Stela in the Central Mexican Highlands Susan D. Gillespie University of Florida It is a little known fact that the Mesoamerican Middle ever, Chalcatzingo’s sculptors also produced motifs, Formative site with the most carved stone stelae is not forms, and spatial patterns that have no known Gulf the major Olmec center of La Venta, but Chalcatzingo coast Olmec connections, such as the quatrefoil (Grove in the highland state of Morelos, Mexico (Grove n.d.) 2000), and some designs show ties to west Mexico and (Figure 1). Chalcatzingo (Grove 1984; Grove, ed. 1987) is to the Pacific slopes and highlands of Chiapas and Gua- justly famous for its stone carvings dating to the Cantera temala (Grove 1989, 1999, 2000). phase, c. 700-500 bc (uncalibrated radiocarbon years). This paper describes a recently discovered These mostly bas-relief sculptures—carved on the face Chalcatzingo stela, Monument 34, carved with motifs of the Cerro Chalcatzingo, on nearby hillside boulders, strikingly reminiscent of later (Late Formative) art- and on free-standing stones—have long been recog- works in southern Mesoamerica, including those in the nized as having affinities with Olmec sculptures on the lowland Maya region. This stela manifests yet another Gulf coast. Their closest stylistic affiliations are with La historical tie between Chalcatzingo and other areas of Venta, and a few motifs are known only at these two Mesoamerica, and it may possibly signal the site’s status sites (Grove 1987b:426-430, 1989:132-142, n.d.). How- as an innovator of important motifs.