NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION Kam Wah Chung

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seattle Tilth. Garden Renovation Plan. Phase 1

seattle tilth. phase 1. conceptual plan. garden renovation plan. seattle tilth. garden renovation plan. phase 1. conceptual plan. acknowledgements. This planning effort was made possible through the support of the City of Seattle Department of Neighborhoods’ Small and Simple Grant and the matching support of members, volunteers and friends of Seattle Tilth. A special thanks to the following gardening experts, landscape architects and architects for their assistance and participation in planning efforts: Carolyn Alcorn, Walter Brodie, Daniel Corcoran, Nancy Evans, Willi Evans Galloway, Eric Higbee, Katrina Morgan, Joyce Moty, Debra Oliver, Cheryl Peterson, Alison Saperstein, Gil Schieber, Brian Shapley, Lisa Sidlauskas, Craig Skipton, Elaine Stannard, Howard Stenn, Jill Stenn, Bill Thorness, Cathy Tuttle, Faith VanDePull, Linda Versage, Lily Warner, Carl Woestwin and Livy Yueh. Staff leadership provided by Kathy Dang, Karen Luetjen, Katie Pencke and Lisa Taylor. Community partners: Historic Seattle, Wallingford Community Senior Center, Wallingford P-Patch, Meridian School, Wallingford Community Council and all of our great neighbors. Many thanks to Peg Marckworth for advice on branding, Allison Orr for her illustrations and Heidi Smets for graphic design. Photography by Seattle Tilth, Heidi Smets, Amy Stanton and Carl Woestwin. We would like to thank the 2008 Architecture Design/Build Studio at the University of Washington for their design ideas and illustration. We would like to thank Royal Alley-Barnes at the City of Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation for reviewing our grant application prior to submittal. written by nicole kistler © 2008 by seattle tilth all rights reserved Seattle Tilth 4649 Sunnyside Avenue North Seattle WA 98103 www.seattletilth.org May 30, 2008 Seattle Tilth is a special place for me. -

Preservationists: Sharpening Our Skills Or Finding Continuing Education

Preservationists: Sharpening our skills or finding continuing education training (whether for ourselves or others) should be a high priority. To make this chore easier, I have compiled a list of activities in the Western United States or those that have special significance. Please take the time to review the list and follow the links. The following is a list of activities you should strongly consider participating in or send a delegate to represent your organization. There are many other training opportunities on the East Coast and if you need more information you can either follow the links or contact me specifically about your needs. The list is not comprehensive and you should check DAHP’s website for updates. For more information contact Russell Holter 360-586-3533. Clatsop Community College in Astoria, Oregon, now offers a Certificate and an Associate’s Degree in Historic Preservation. For more information about their class offerings, please see their website www.clatsopcc.edu. There could be scholarship opportunities available depending upon which course interests you. Please enquire with DAHP or visit the website associated with each listing. February 22 Preserving Stain Glass Historic Seattle Seattle, WA www.historicseattle.org February 24-26 Section 106: Agreement Documents National Preservation Institute Honolulu, HI www.npi.org February 25 Historic Structures Reports National Preservation Institute Los Angeles, CA www.npi.org February 26-27 Preservation Maintenance National Preservation Institute Los Angeles, CA www.npi.org -

Historic Seattle 2016 Programs Historic Seattle

HISTORIC SEATTLE 2016 PROGRAMS HISTORIC SEATTLE HISTORIC SEATTLE is proud to offer an outstanding 2016 educational program for lovers of buildings and heritage. 2016 Enjoy lectures and workshops, private home, local, and out-of-town tours, informal advocacy-focused, issues- PROGRAMS based events, and special opportunities that bring you closer to understanding and PAGE appreciating the rich and varied JANUARY built environment that we seek 26 (TUES) Members Meeting: German House 3 to preserve and protect with your help. FEBRUARY 6 (SAT) Workshop: Digging Deeper: Pacific Northwest Railroad Archive 7 20 (SAT) Tour: Religious Life off Campus: University District Churches 10 28 (SUN) Documentary Screening: Bungalow Heaven 4 MARCH 8 (TUES) Tour: First Hill Neighborhood 10 9 (WED) Lectures: Gardens of Eden: American Visions of Residential Communities 4 12 (SAT) Workshop: Digging Deeper: Special Collections, University of Washington 7 26 (SAT) Tour: Georgetown Steam Plant 11 APRIL 2 (SAT) Tour: Montlake 11 4 (MON) Members Meeting: Congregation Shevet Achim 3 9 (SAT) Workshop: Digging Deeper: Seattle Theatre Group Library 7 23 (SAT) Tour A: Behind the Garden Wall: Good Shepherd Center Gardens 8 30 (SAT) Tour B: Behind the Garden Wall: Good Shepherd Center Gardens 8 COVER PHOTO MAY From “Seattle: In the Charmed Land,” 7 (SAT) Workshop: Digging Deeper: Ballard Historical Society 7 Seattle Chamber of Commerce, 1932 9 (MON) Lecture: The Impact of World War I on Seattle and its Cityscape 5 Collection of Eugenia Woo 22 (SUN) Tour: Bloxom Residence, -

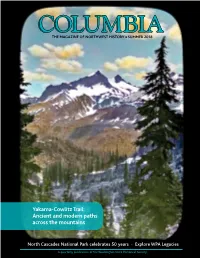

Yakama-Cowlitz Trail: Ancient and Modern Paths Across the Mountains

COLUMBIA THE MAGAZINE OF NORTHWEST HISTORY ■ SUMMER 2018 Yakama-Cowlitz Trail: Ancient and modern paths across the mountains North Cascades National Park celebrates 50 years • Explore WPA Legacies A quarterly publication of the Washington State Historical Society TWO CENTURIES OF GLASS 19 • JULY 14–DECEMBER 6, 2018 27 − Experience the beauty of transformed materials • − Explore innovative reuse from across WA − See dozens of unique objects created by upcycling, downcycling, recycling − Learn about enterprising makers in our region 18 – 1 • 8 • 9 WASHINGTON STATE HISTORY MUSEUM 1911 Pacific Avenue, Tacoma | 1-888-BE-THERE WashingtonHistory.org CONTENTS COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History A quarterly publication of the VOLUME THIRTY-TWO, NUMBER TWO ■ Feliks Banel, Editor Theresa Cummins, Graphic Designer FOUNDING EDITOR COVER STORY John McClelland Jr. (1915–2010) ■ 4 The Yakama-Cowlitz Trail by Judy Bentley OFFICERS Judy Bentley searches the landscape, memories, old photos—and President: Larry Kopp, Tacoma occasionally, signage along the trail—to help tell the story of an Vice President: Ryan Pennington, Woodinville ancient footpath over the Cascades. Treasurer: Alex McGregor, Colfax Secretary/WSHS Director: Jennifer Kilmer EX OFFICIO TRUSTEES Jay Inslee, Governor Chris Reykdal, Superintendent of Public Instruction Kim Wyman, Secretary of State BOARD OF TRUSTEES Sally Barline, Lakewood Natalie Bowman, Tacoma Enrique Cerna, Seattle Senator Jeannie Darneille, Tacoma David Devine, Tacoma 14 Crown Jewel Wilderness of the North Cascades by Lauren Danner Suzie Dicks, Belfair Lauren14 Danner commemorates the 50th22 anniversary of one of John B. Dimmer, Tacoma Washington’s most special places in an excerpt from her book, Jim Garrison, Mount Vernon Representative Zack Hudgins, Tukwila Crown Jewel Wilderness: Creating North Cascades National Park. -

Historic-Seattle-2017-Programs

1117 MINOR AVENUE SEATTLE, WA 98101 Bothell City Hall Golden Gardens Park Bathhouse WHEN: Monday, January 30, 4:00 – 5:30 PM WHEN: Monday, April 10, 4:00 – 5:30 PM WHERE: 18415 101st Avenue Northeast, Bothell WHERE: 8498 Seaview Place Northwest Registration: Donations accepted Registration: Donations accepted Complimentary parking in City Hall Garage The historic Golden Gardens Bathhouse, located Meet at Bothell’s new City Hall, designed by north of the Shilshole Bay Marina, housed a Miller Hull Partnership, and hear about the changing room, storage facility, and a lifeguard Bothell renaissance and the adaptive reuse of an station. Built in the 1930s, it was closed in 1974 important cultural icon, Anderson School, into a due to limited funds. It reopened in 1994 as a new McMenamins hotel complex. Speakers drop-in center for at-risk youth. Pro Parks Levy include David Boyd, City of Bothell (COB) Senior funds from 2000 were used for its renovation in Planner, and Davina Duerr, Deputy Mayor. Joining 2004. Independent heating keeps the bathhouse HISTORIC SEATTLE them will be Tim Hills, Kerry Beeaker, and Emlyn warm in the winter, and cross ventilation keeps THANK YOU TO OUR 2017 SPONSORS WHOSE Bruns, sta of McMenamins’ History Department. it cool in the summer. Kathleen A. Conner, AICP, They will speak to the role that history plays in Planning Manager, Seale Parks and Recreation, 2017 PROGRAMS this and other projects, and conduct tours of the will discuss this project and the role of the SUPPORT MAKES THESE PROGRAMS POSSIBLE. McMenamins campus. Stay aerwards for drinks department in preserving and maintaining the and/or dinner at one of their restaurants or bars city’s historic Olmsted parks and boulevards, while (including a Tiki-themed one). -

Historic Preservation Commission Applications

From: [email protected] To: City Admin Subject: Online Form Submittal: City Advisory Group Application Date: Thursday, June 11, 2020 12:56:11 PM City Advisory Group Application Step 1 Please complete the form below if you are interested in serving on a committee or commission. Once completed, this form will become part of the City's Volunteer Roster. Please note: once submitted, this application becomes a public record. Your address and contact information will not be shared. Applicant Name Terri Bumgardner Email Phone Address City Bainbridge Island State WA Zip 98110 Current Employer Retired Environmental/City Planner City of San Diego Current Position Private Land Use Consult I am interested in Climate Change Advisory Committee , Environmental Technical serving on one of the Advisory Committee, Historic Preservation Commission following City advisory groups (select all that apply): Experience & Qualifications Have you served on No any City advisory groups in the past? If so, please indicate Field not completed. which groups: Please share your I have over 40 years of Planning, Land Use, Environmental qualifications for this review, and Historical review of Projects. appointment (skills, activities, training, education) if any: Please share your I am interested in community service, maintaining and improving community interests the Environmental health of the Island. I love working in Public (groups, committees, Service. I am new to the Island but feel I need to become organizations) if any: involved and this would give me an opportunity to meet people. ( If a resume is needed I would be glad to provide one, however I worked for the City of San Diego from 1988 to 2014 in General Services for 3 years and Planning and Building Department for the rest of my tenure, and as a private Land Use Consultant to present). -

Historic Seattle

Historic seattle 2 0 1 2 p r o g r a m s WHat’s inside: elcome to eattle s premier educational program for learning W s ’ 3 from historic lovers of buildings and Heritage. sites open to Each year, Pacific Northwest residents enjoy our popular lectures, 4 view tour fairs, private home and out-of-town tours, and special events that foster an understanding and appreciation of the rich and varied built preserving 4 your old environment that we seek to preserve and protect with your help! house local tours 5 2012 programs at a glance January June out-of-town 23 Learning from Historic Sites 7 Preserving Utility Earthwise Salvage 5 tour Neptune Theatre 28 Special Event Design Arts Washington Hall Festive Partners’ Night Welcome to the Future design arts 5 Seattle Social and Cultural Context in ‘62 6 February 12 Northwest Architects of the Seattle World’s Fair 9 Preserving Utility 19 Modern Building Technology National Archives and Record Administration preserving (NARA) July utility 19 Local Tour 10 Preserving Utility First Hill Neighborhood 25 Interior Storm Windows Pioneer Building 21 Learning from Historic Sites March Tukwila Historical Society special Design Arts 11 events Arts & Crafts Ceramics August 27 Rookwood Arts & Crafts Tiles: 11 Open to View From Cincinnati to Seattle Hofius Residence 28 An Appreciation for California Ceramic Tile Heritage 16 Local Tour First Hill Neighborhood April 14 Preserving Your Old House September Building Renovation Fair 15 Design Arts Cover l to r, top to bottom: Stained Glass in Seattle Justinian and Theodora, -

Barrientos RYAN

development barrientos project management real estate Maria Barrientos, principal qualifications Ms. Barrientos has over thirty years of experience in real estate development, project management, and construction administration. She has successfully managed the development and construction of over $900 million worth of projects in the last thirty plus years. Ms. Barrientos’ strong inter-personal communication skills, strategic thinking, leadership abilities and problem-solving capabilities enable her to successfully analyze challenging problems and work towards workable positive solutions. Ms. Barrientos also spends considerable time as a volunteer on numerous community- based organizations. Ms. Barrientos is the Managing Member and Principal of Barrientos LLC. experience January 1999 – present barrientos LLC Seattle, WA For the past 13 years, barrientos has provided real estate development services for the development of real estate projects in a combination of private development, fee development work, and project management for both public and private entities. Projects completed or under construction while at barrientos include: HOUSING PROJECTS Youngstown Flats - Mixed Use Apartment Development Project Barrientos has teamed up with Legacy Residential Partners to develop this unique apartment building located just 2 blocks south of the west Seattle bridge off of north Delridge and SW Dakota Street. This 185 unit building is located just east of the Longfellow Creek Trail with easy access to lots of green open space. This new $50 million apartment building will start construction in mid-August 2011 and includes 2 levels of below grade parking. The project will be completed early spring 2013. Ruby Condominiums - Mixed Use Apartment Development Project Barrientos was the owner/developer for this condominium project located at the northern edge of Eastlake at 2960 Eastlake Avenue North, just 2 block south of the University Bridge. -

2016 Training Opportunities

2016 TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES Looking to learn more about Historic Preservation? Here are some helpful links: Sharpening our skills or finding continuing education training (whether for ourselves or others) should be a high priority. To make this chore easier, I have compiled a list of activities in the Western United States or those that have special significance. Please take the time to review the list and follow the links. The following is a list of activities you should strongly consider participating in or send a delegate to represent your organization. There are many other training opportunities on the East Coast and if you need more information you can either follow the links or contact me specifically about your needs. The list is not comprehensive and you should check DAHP’s website for updates. For more information contact Russell Holter 360-586-3533. There could be scholarship opportunities available depending upon which course interests you. Please enquire with DAHP or visit the website associated with each listing. JANUARY 27-28 NAGPRA: Preparing for & Writing Grant Proposals National Preservation Institute Phoenix, AZ www.npi.org FEBRUARY 2 NAGPRA Essentials National Preservation Institute Anchorage, AK www.npi.org 3-4 NAGPRA: Preparing for & Writing Grant Proposals National Preservation Institute Anchorage, AK www.npi.org 6 Digging Deeper—Pacific Northwest Railroad Archives Historic Seattle Burien, WA www.historicseattle.org 23-24 Historic Windows: Managing for Preservation, Maintenance & Energy Conservation National Preservation -

Gail Christie-Jahn Sunny Jim 22 X 28 $200.00

HISTORIC SEATTLE & GEORGETOWN ART ATTACK: A Group Show & Sale Palace Theatre & Art Bar December 14, 2019 | 4-8 PM HISTORIC SEATTLE’S 2019 EDUCATION PROGRAMS ARE MADE POSSIBLE BY SUPPORT FROM: UNDERWRITING PARTNERS Bassetti Architects SUSTAINING PARTNERS Bennett Properties | Daniels Real Estate | Lydig Construction | Marvin Anderson Architects | Pacifica Law Group PRESENTING PARTNERS Bear Wood Windows | Beneficial State Bank | BOLA Architecture + Planning | Bricklin & Newman | BuildingWork | Chosen Wood Window Maintenance, Inc. | J.A.S. Design Build | Lease Crutcher Lewis | National Trust Insurance Services | Ron Wright Associates / Architects | SHKS | Swenson Say Fagét | Third Place Design Cooperative | Tonkin Architecture | Tru Mechanical | Watson & McDonell AND ADDITIONAL SUPPORT FROM: 4Culture | City of Seattle Office of Arts & Culture SAVE MEANINGFUL PLACES | SUPPORT LOCAL ARTISTS Thank you, Palace Theatre & Art Bar for your overwhelming enthusiasm for this project, and for your commitment to hosting this show. Thanks to the Georgetown Merchants Association for welcoming us as part of Georgetown Art Attack. Gratitude to the artists for their generosity and creativity, each capturing their own unique idea of “historic Seattle.” This collection inspires us to continue our mission to save meaningful places that foster lively communities. And finally, we are grateful to you! 50% of proceeds from art sold tonight supports Historic Seattle’s mission, the remainder goes to the individual artists. We are grateful for your support! Remember, sales close at 8pm and all artwork will be sold first come, first serve — so if you see a piece you love, let us know! We’re happy to hold artwork you purchase at this show while you enjoy the rest of Art Attack. -

Motion 10792

10792 09117/1999 Greg Nickels Rob McKenna Introduced By: . Larry Phillips 99HSP Motion Clerk 09120199 Proposed No.: 1999-0541 1 II MOTION NO 10792 2 A MOTION approving projects for the King County 3 landmarks and heritage special projects program, in 4 accordance with Ordinance 11242 .. 5 II WHEREAS, the King County landmarks and heritage commission is authorized by 6 II Ordinance 11242 to administer the special projects programs, and 7 II WHEREAS, the King County office of cultUral resources received forty-nine 8 II applications requesting $399,642 from the 1999 landmarks and heritage special projects· 9 II programs, and 10 II WHEREAS, a review panel comprised of historians, anthropologists, heritage 11 II museum professionals, community representatives and commission members reviewed the 12 II applications and made recommendations to the King County landmarks and heritage 13 II commission, and 14 II WHEREAS, the King County landmarks and heritage commission approved the 15 /I recommendations, as listedin Attachment A,and 16 /I WHEREAS, the recommendations for the landmarks and heritage special projects 17 /I adhere to the guidelines and financial plan approved by the King County council in Motion 18 II 8797, and - 1 - 10792 1 II WHEREAS, the financial plan included as Attachment C, has been revised to 2 II indiCate actual hotel/motel tax revenue for 1999; 3 II NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT MOVED by the Council of King County: 4 II The executive is hereby authorized to allocate $158,262 in support of thirty-two 5 II landmarks and heritage special projects as listed in Attachment A, from the following 6 II source: 7 Arts and cultural development fund 117 $158,262 8 PASSED by a vote of 11 to 0 this 11th day of October, 1999. -

September 14, 2016 Megan Duvall, Historic Preservation Officer City Of

September 14, 2016 Megan Duvall, Historic Preservation Officer City of Spokane City Hall, Third Floor 808 W Spokane Falls Boulevard Spokane, Washington 99201 Via email: [email protected] RE: City of Spokane Mid-20th Century Modern Context Statement and Inventory Dear Ms. Duvall: Preservation Solutions LLC (PSLLC) is delighted to submit this response to the City/County of Spokane’s Request for Proposals for professional services relating to a survey of mid-20th century architecture and the development of a historic context. As you will see in the qualifications outlined herein, our project team is uniquely qualified for this scope of work. Comprised of three professional architectural historians with a combined half-century of experience, the Preservation Solutions consulting team has extensive experience in the identification, evaluation, planning, protection, and successful nomination of cultural properties, totaling well over 23,000 resources documented nationwide. Each team member’s experience not only exceeds the qualifications for historic preservation professionals outlined by the National Park Service, but includes demonstrated familiarity with comparable studies of mid-century resources combined with public engagement and planning components. You will find this combination of skills and experience will be an asset to the project and ensures documentation of mid-century Spokane and recommendations for its future preservation will rely on the judgment of professionals trained in all National Register criteria. Furthermore, we are proud to offer two public meetings and four options of additional deliverables from which the City/County can choose. In our experience working with communities of all sizes in various states, we have found preservation works best when it is tailored to unique local conditions and perspectives.