Legislative Budget and Finance Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Scorecard

2020 LEGISLATIVE SCORECARD 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 .........................................SCORING METHODOLOGY 05 ..................... LETTER FROM THE STATE DIRECTOR 06 .................................................... BILL DESCRIPTIONS 14 ............................................................... SENATE VOTES 18 ..................................................................HOUSE VOTES www.AmericansForProsperity.org/Pennsylvania 3 FELLOW PENNSYLVANIANS, Thank you for your interest in the 2019-2020 Americans for Prosperity- Pennsylvania (AFP-PA) Legislative Scorecard. Our goal with the scorecard is simple: to make the government more accountable to the people. People are capable of extraordinary things when provided with the freedom and opportunity to do so. Based on that belief, our team of dedicated staff and activists works tirelessly on the most pressing public policy issues of our time to remove barriers to opportunity to ensure that every Pennsylvanian can reach their full potential, and have the best shot at their unique version of the American Dream. Through continuous engagement, our grassroots activists across the Keystone State build connections between lawmakers and the constituents they serve to transform the key institution of government. It begins with welcoming everyday citizens that are motivated to join our charge so that we can elevate and amplify their voices in public policy—making them more powerful and influential than they could be on their own. It comes full circle when AFP-PA successfully mobilizes activists in support of principled policy leadership or to hold lawmakers accountable for harmful policies. It is about consistently pushing activists and lawmakers alike to be better and make a difference. From building diverse coalitions or providing lawmakers with the support they need to stand on principle, this approach has allowed our organization to emerge as a change-maker in the state. -

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Legislative

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA LEGISLATIVE JOURNAL MONDAY, JANUARY 26, 2009 SESSION OF 2009 193D OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY No. 2 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JOURNAL APPROVAL POSTPONED The House convened at 1 p.m., e.s.t. The SPEAKER. Without objection, approval of the Journal of Tuesday, January 6, 2009, will be postponed until printed. THE SPEAKER (KEITH R. McCALL) The Chair hears no objection. PRESIDING LEAVES OF ABSENCE PRAYER The SPEAKER. Turning to leaves of absence, the Chair The SPEAKER. The prayer will be offered by Pastor recognizes the majority whip, Representative DeWeese, who Ricky Phillips, who is a guest of the Honorable Representative requests the following leaves: the gentleman from Bucks, Bud George. Mr. GALLOWAY, for the day; the gentleman from Erie, Mr. HORNAMAN, for the day; the gentleman from Allegheny, PASTOR RICKY PHILLIPS, Guest Chaplain of the House Mr. Matt SMITH, for the day; the gentleman from of Representatives, offered the following prayer: Montgomery, Mr. CURRY, for the day; and the gentleman from Washington, Mr. DALEY, for the day. Without objection, the Let us pray: leaves will be granted. God of all creation, You are the source of all wisdom and The Chair also recognizes the gentleman, Mr. Turzai, who love. You have created all of us, and as individuals, we are all requests the following leaves: the gentleman from Delaware, different in many ways. We thank You for this diversity. Help Mr. CIVERA, for the week; the gentleman from Lancaster, us to celebrate this diversity by working together so that we can Mr. HICKERNELL, for the day; and the gentleman from appreciate the true beauty of creation in all of its fullness. -

LRI's Rev Up! Philadelphia 2018 Booklet

Register, Educate, Vote, Use Your Power Full political participation for Americans with disabilities is a right. AAPD works with state and national coalitions on effective, non- partisan campaigns to eliminate barriers to voting, promoting accessible voting technology and polling places; educate voters about issues and candidates; promote turnout of voters with disabilities across the country; protect eligible voters’ right to participate in elections; and engage candidates and elected officials to recognize the disability community. 1 Pennsylvania 2018 Midterm Election Dates 2018 Pennsylvania Midterm Election Registrations Date: Tuesday, October 9, 2018 – DEADLINE!! 2018 Pennsylvania Midterm Elections Date: Tuesday, November 6, 2018, 7 am – 8 pm Pennsylvania Voter Services https://www.pavoterservices.pa.gov • Register to Vote • Apply for An Absentee Ballot • Check Voter Registration Status • Check Voter Application Status • Find Your Polling Place 2 Table of Contents Pennsylvania 2018 Midterm Election Dates ............................ 2 2018 Pennsylvania Midterm Election Registrations ................. 2 2018 Pennsylvania Midterm Elections .................................. 2 Table of Contents ................................................................ 3 Voting Accommodations ....................................................... 7 Voter Registration ............................................................ 7 Language Access ................................................................ 8 Issues that Affect People with Disabilities -

Pennsylvania State Veterans Commission 05 February 2021 at 10:00 AM Virtual Meeting

Pennsylvania State Veterans Commission 05 February 2021 at 10:00 AM Virtual Meeting 1000 (5) CALL TO ORDER Chairman Sam Petrovich Moment of Silence Vice-Chairman Nick Taylor Pledge of Allegiance Chairman Sam Petrovich 1005 (5) Commission Introduction Chairman Sam Petrovich 1010 (3) Oath of Office MG Mark Schindler Robert Forbes- AMVETS 1013 (3) Approval of 4 December meeting minutes REQUIRES A VOTE 1016 (10) DMVA Military Update MG Mark Schindler 1026 (15) VISN 4 Mr. Tim Liezert OLD BUSINESS NEW BUSINESS 1041 (5) DMVA, Policy, Planning & Legislative Affairs Mr. Seth Benge 1046 (10) DMVA, Bureau of Veterans Homes Mr. Rich Adams 1056 (10) DMVA, Bureau of Programs, Initiatives, Reintegration and Outreach (PIRO) Mr. Joel Mutschler SC 1106 (4) Approval of Programs Report (Report provided by DMVA) REQUIRES A VOTE 1110 (5) Act 66 Committee report Mr. Anthony Jorgenson 1115 (5) RETX Committee report Mr. Justin Slep 1120 (5) Legislative Committee report Chairman Sam Petrovich 1125 (5) Pensions & Relief/Grave markings Committee report Ms. Connie Snavely 1135 (10) Member-at-Large Committee Chairman Sam Petrovich 1145 (10) Good of the Order Chairman Sam Petrovich 1155 (5) Next Meeting: April 2, 2021 Webex Virtual 1200 ADJOURNMENT Chairman Sam Petrovich RETIRING OF COLORS Chairman Sam Petrovich State Veterans Commission Meeting Minutes December 4, 2020 10:00 AM to 11:48 AM Webex Video Teleconference Call to Order Chairman Samuel Petrovich The Pennsylvania State Veterans Commission (SVC) meeting was called to order at 10:00 AM by Chairman Samuel Petrovich. Moment of Silence and Pledge of Allegiance The meeting was opened with a moment of silence for the upcoming 79th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance led by Chairman Samuel Petrovich. -

Senate Leaders • Sen

The Pennsylvania House and Senate announced their 2019-2020 committee leaders. Why should I care? Committee leaders are influential members of the Pa. General Assembly. Strong relationships between them, PAMED, and physician members are key. Here are the announced committee leaders. While it may seem like some of them have nothing to do with the practice of medicine, all chairs are included because history has shown that legislation that affects physicians can get assigned to a seemingly unrelated committee due to the bill’s contents. Therefore, it’s good for physicians to be aware of all committee leaders in the Pa. General Assembly. Senate Leaders • Sen. Joe Scarnati (Jefferson) – President Pro Tempore • Sen. Jake Corman (Centre) – Majority Leader • Sen. Patrick Browne (Lehigh) – Appropriations Chairman • Sen. John Gordner (Columbia) – Majority Whip • Sen. Bob Mensch (Montgomery) – Caucus Chair • Sen. Richard Alloway (Franklin) – Caucus Secretary • Sen. David Argall (Schuylkill) – Policy Chair • Sen. Jay Costa (Allegheny) – Minority Leader • Sen. Vincent Hughes (Philadelphia) – Appropriations Chairman • Sen. Anthony Williams (Philadelphia) – Minority Whip • Sen. Wayne Fontana (Allegheny) – Caucus Chair • Sen. Larry Farnese (Philadelphia) – Caucus Secretary • Sen. John Blake (Lackawanna) – Caucus Administrator • Sen. Lisa Boscola (Northampton) – Policy Chair Aging & Youth • Sen. John DiSanto – R, Dauphin and Perry counties • Sen. Maria Collett – D, Bucks and Montgomery counties Agriculture & Rural Affairs • Sen. Elder Vogel, Jr. – R, Beaver, Butler, and Lawrence counties • Sen. Judy Schwank – D, Berks County Appropriations • Sen. Pat Browne – R, Lehigh County • Sen. Vincent Hughes – D, Montgomery and Philadelphia counties Banking & Insurance* • Sen. Don White – R, Armstrong, Butler, Indiana, and Westmoreland counties • Sen. Sharif Street – D, Philadelphia County Communications & Technology • Sen. -

Senator Michele Brooks, Senator Joseph Scarnati, Senator John Gordner, Senator Ryan Aument, Senator Mario Scavello, Senator Kim Ward

Received 7/12/2019 3:00:53 PM Supreme Court Eastern District Filed 7/12/2019 3:00:00 PM Supreme Court Eastern District 102 EM 2018 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PENNSYLVANIA No. 102 EM 2018 & 103 EM 2018 JERMONT COX and KEVIN MARINELLI, Petitioners, v. COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, Respondent. BRIEF FOR AMICUS CURIAE OF SENATOR SCOTT MARTIN, SENATOR GENE YAW, SENATOR SCOTT HUTCHINSON, SENATOR MIKE FOLMER, SENATOR LISA BAKER, SENATOR WAYNE LANGERHOLC, SENATOR CAMERA BARTOLOTTA, SENATOR MICHELE BROOKS, SENATOR JOSEPH SCARNATI, SENATOR JOHN GORDNER, SENATOR RYAN AUMENT, SENATOR MARIO SCAVELLO, SENATOR KIM WARD Matthew H. Haverstick (No. 85072) Mark E. Seiberling (No. 91256) Joshua J. Voss (No. 306853) Shohin H. Vance (No. 323551) KLEINBARD LLC Three Logan Square 1717 Arch Street, 5th Floor Philadelphia, PA 19103 Ph: (215) 568-2000 / Fax: (215) 568-0140 Eml: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Senator Scott Martin, Senator Gene Yaw, Senator Scott Hutchinson, Senator Mike Folmer, Senator Lisa Baker, Senator Wayne Langerholc, Senator Camera Bartolotta, Senator Michele Brooks, Senator Joseph Scarnati, Senator John Gordner, Senator Ryan Aument, Senator Mario Scavello, Senator Kim Ward ii TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. STATEMENT OF INTEREST 1 III.ARGUMENT 4 A. The purpose of the JSGC Report was to give guidance to the General Assembly on potential legislative changes; it was not intended to stand in for judicial fact-finding or to eliminate important policy debates. 4 B. To preserve the General Assembly's ability to fix any statutes that need remedied, the Court should treat this matter as an as -applied challenge, and not as the facial challenge it attempts to lodge sub silentio. -

1 1 House of Representatives

1 1 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA 2 HOUSE AGRICULTURE AND RURAL AFFAIRS COMMITTEE AND 3 HOUSE EDUCATION COMMITTEE JOINT PUBLIC HEARING 4 AG PROGRESS DAYS 5 THEATER AREA ROUTE 45 6 ROCK SPRINGS, PA 7 WEDNESDAY AUGUST 15, 2007, 10:00 A.M. TO 12:00 NOON 8 BEFORE: HONORABLE MICHAEL K. HANNA, MAJORITY CHAIRMAN 9 HONORABLE ARTHUR HERSHEY, MINORITY CHAIRMAN HONORABLE DAVID R. KESSLER, SECRETARY 10 HONORABLE BOB BASTIAN HONORABLE MICHELE BROOKS 11 HONORABLE MIKE CARROLL HONORABLE H. SCOTT CONKLIN 12 HONORABLE LAWRENCE CURRY HONORABLE GORDON DENLINGER 13 HONORABLE MIKE FLECK HONORABLE DAVID S. HICKERNELL 14 HONORABLE ROB KAUFFMAN HONORABLE MARK KELLER 15 HONORABLE BERNARD O'NEILL HONORABLE TINA PICKETT 16 HONORABLE KATHY RAPP HONORABLE TIMOTHY SOLOBAY 17 HONORABLE TOM YEWCIC 18 ALSO PRESENT: DIANE W. HAIN, MAJORITY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 19 KERRY GOLDEN, MINORITY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DAVE CALLEN, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR/COMMERCE COMMITTEE 20 JAY HOWES, DIRECTOR OF POLICY DEVELOPMENT ALYCIA LAURETI, RESEARCH ANALYST 21 22 JO NELL SNIDER, REPORTER 23 NOTARY PUBLIC 24 Jo Nell Snider Court Reporting Service 25 P. O. Box 202 East Freedom, PA 16637 2 1 I N D E X 2 TESTIFIERS: PAGE 3 The Pennsylvania State University 4 Robert D. Steele, PhD 8 Dean, College of Agricultural Sciences 5 PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE 6 Hon. Dennis M. Wolff 28 Secretary of Agriculture 7 W. B. SAUL HIGH SCHOOL OF AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES 8 Wendy Shapiro, Principal 44 9 FUTURE FARMERS OF AMERICA Tiffany Grove, State President 59 10 PENNSYLVANIA VETERINARY MEDICAL ASSOCIATION 11 David R. Wolfgang, VMD 66 12 PENNSYLVANIA FARM BUREAU Gary Swan, Director of Governmental Affairs 13 and Communications 75 14 PENN AG INDUSTRIES Christian Herr, Assistant Vice President 77 15 PENNSYLVANIA FARMERS UNION 16 Larry Breech, President 79 17 PENNSYLVANIA STATE GRANGE 80 Betsy Huber, President 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 3 1 CHAIRMAN HANNA: Once again, good morning. -

November 7, 2018 Pennsylvania Was One of the Most Closely Watched

Keep up to date with our blog: Follow us on Twitter @BuchananGov knowingGovernmentRelations.com November 7, 2018 Pennsylvania was one of the most closely watched states in the country on Election Day. Redistricting of Congressional seats meant a shakeup was coming for the Commonwealth’s 18-member delegation. At the statewide level, the Governor and one of two U.S. Senators were on the ballot. In the state legislature, half of the 50 Senate seats (even- numbered districts) and the entire 203-seat House of Representatives were up for grabs. During the 2017-18 legislative session the Pennsylvania House of Representatives was comprised of 121 Republicans and 82 Democrats. After last night’s election, the 2018-19 legislative session will have 109 Republicans and 94 Democrats, after the Democrats picked up 11 seats. In the Pennsylvania Senate, Republicans had a majority during the 2017-18 by a margin of 34-16. Yesterday, Senate Democrats picked up 5 seats, narrowing the Republican’s majority. Next session will have 29 Republican members and 21 Democratic members. The 18-member Pennsylvania delegation had only 6 Democrats during the 115th Congress (2017-19). When new members are sworn into the 116th Congress next year, Pennsylvania’s delegation will be split, with 9 Republicans and 9 Democrats. Governor Governor Tom Wolf (D) and his running mate for Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman (D) defeated the ticket of Scott Wagner (R) and Jeff Bartos (R). Wolf received 2,799,1559 votes (57.66%), while Wagner got 1,981,027 votes (40.81%). U.S. Senate Senator Bob Casey (D) defeated Lou Barletta (R) by a margin of over half a million votes. -

Contents Around the Rotunda Around the Rotunda

November 15 - 21, 2019 Contents Around the Rotunda Around the Rotunda ...... 1 Committee News ......... 1 No Around the Rotunda this week. Bullet.in.Points .......... 13 Committee News Cosponsor Memos ....... 14 Bill Actions ............. 14 House Transportation Committee 11/18/19, 11:30 a.m., Room B-31, Main Capitol Building Upcoming Events ........ 27 By Sheri Melnick, Pennsylvania Legislative Services In the News ............. 28 The committee met to consider legislation. SESSION STATUS At 3:53 p.m. on Thursday, Chairman Tim Hennessey (R-Chester) noted that “the big item on the agenda” is the November 21, 2019 the authorization of radar by municipalities other than state police. Senate stands in recess until the call of the President Pro HB 1536 Miller, Brett - (PN 1954) Amends Title 75 (Vehicles) defining “vulnerable highway Tempore. user” as a pedestrian or a person on roller skates, inline skates, a skateboard, motor- driven cycle, motorcycle, pedalcycle, motorized pedalcycle, pedalcycle with electric assist, At 3:33 p.m. on Thursday, an animal, an animal-drawn vehicle, a farm vehicle or a wheelchair. Also increases the November 21, 2019 the penalties for a person convicted of careless driving that results in the death, seriously bodily House stands adjourned until injury or bodily injury of a vulnerable highway user. Effective in 120 days. - The bill was Monday, December 16, 2019 unanimously reported as amended. at 1:00 p.m., unless sooner recalled by the Speaker. A03771 by Hennessey, reduces certain penalties and makes technical changes. The amendment was unanimously adopted. UPCOMING SESSION DAYS Rep. Brett Miller (R-Lancaster) explained that this bill pertains to an issue brought to his attention by a constituent and noted that the bill passed out of committee unanimously last House session. -

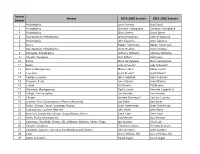

2021-2022 Members of the PA Senate

Senate County 2019-2020 Senator 2021-2022 Senator District 1 Philadelphia Larry Farnese Nikil Saval 2 Philadelphia Christine Tartaglione Christine Tartaglione 3 Philadelphia Sharif Street Sharif Street 4 Montgomery, Philadelphia Arthur Haywood Arthur Haywood 5 Philadelphia John Sabatina John Sabatina 6 Bucks Robert Tomlinson Robert Tomlinson 7 Montgomery, Philadelphia Vince Hughes Vince Hughes 8 Delaware, Philadelphia Anthony Williams Anthony Williams 9 Chester, Delaware Tom Killion* John Kane 10 Bucks Steve Santarsiero Steve Santarsiero 11 Berks Judy Schwank* Judy Schwank* 12 Bucks, Montgomery Maria Collett Maria Collett 13 Lancaster Scott Martin* Scott Martin* 14 Carbon, Luzerne John Yudichak John Yudichak 15 Dauphin, Perry John DiSanto John DiSanto 16 Lehigh Pat Browne Pat Browne 17 Delaware, Montgomery Daylin Leach Amanda Cappelletti 18 Lehigh, Northampton Lisa Boscola Lisa Boscola 19 Chester Andrew Dinniman* Carolyn Comitta 20 Luzerne, Pike, Susquehanna, Wayne, Wyoming Lisa Baker Lisa Baker 21 Butler, Clarion, Forest, Venango, Warren Scott Hutchinson Scott Hutchinson 22 Lackawanna, Luzerne, Monroe John Blake John Blake 23 Bradford, Lycoming, Sullivan, Susquehanna, Union Gene Yaw* Gene Yaw* 24 Berks, Bucks, Montgomery Bob Mensch Bob Mensch 25 Cameron, Clearfield, Clinton, Elk, Jefferson, McKean, Potter, Tioga Joe Scarnati Cris Dush 26 Chester, Delaware Timothy Kearney Timothy Kearney 27 Columbia, Luzerne, Montour, Northumberland, Snyder John Gordner John Gordner 28 York Kristin Phillips-Hill Kristin Phillips-Hill 29 Berks, Schuylkill -

Legislative Budget and Finance Committee

Legislative Budget and Finance Committee A JOINT COMMITTEE OF THE PENNSYLVANIA GENERAL ASSEMBLY Offices: Room 400 Finance Building, 613 North Street, Harrisburg Mailing Address: P.O. Box 8737, Harrisburg, PA 17105-8737 Tel: (717) 783-1600 • Fax: (717) 787-5487 • Web: http://lbfc.legis.state.pa.us SENATORS ROBERT B. MENSCH Chairman JAMES R. BREWSTER Vice Chairman MICHELE BROOKS THOMAS McGARRIGLE CHRISTINE TARTAGLIONE JOHN N. WOZNIAK Study of Family Work Support Programs REPRESENTATIVES ROBERT W. GODSHALL Secretary JAKE WHEATLEY Treasurer STEPHEN E. BARRAR JIM CHRISTIANA SCOTT CONKLIN PETER SCHWEYER Conducted Pursuant to Senate Resolution 2013-62 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR PHILIP R. DURGIN December 2015 Table of Contents Page Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations ...................................... S-1 I. Introduction ........................................................................................ 1 II. Findings .............................................................................................. 5 A. When Taken Together, the Major Benefit Programs for Low Income Families, Such as TANF, SNAP, EITC, and the Child Tax Credit, Reduce the Number of Households in Poverty Headed by Single Mothers by About 40 Percent, From 48 Percent to 28 Percent. .............. 5 B. Pennsylvania Has Implemented Several Options to Ease the “Cliff” When Moving From Welfare to Work ...................................................... 8 C. About 870,000 Pennsylvania Households (1.8 Million Individuals) Participate in the SNAP (Food Stamp) Program, -

2017-Year-End-Political-Report.Pdf

1 Verizon Political Activity January – December 2017 A Message from Craig Silliman Verizon is affected by a wide variety of government policies -- from telecommunications regulation to taxation to health care and more -- that have an enormous impact on the business climate in which we operate. We owe it to our shareowners, employees and customers to advocate public policies that will enable us to compete fairly and freely in the marketplace. Political contributions are one way we support the democratic electoral process and participate in the policy dialogue. Our employees have established political action committees at the federal level and in 18 states. These political action committees (PACs) allow employees to pool their resources to support candidates for office who generally support the public policies our employees advocate. This report lists all PAC contributions, corporate political contributions, support for ballot initiatives and independent expenditures made by Verizon and its affiliates during 2017. The contribution process is overseen by the Corporate Governance and Policy Committee of our Board of Directors, which receives a comprehensive report and briefing on these activities at least annually. We intend to update this voluntary disclosure twice a year and publish it on our corporate website. We believe this transparency with respect to our political spending is in keeping with our commitment to good corporate governance and a further sign of our responsiveness to the interests of our shareowners. Craig L. Silliman Executive Vice President, Public Policy and General Counsel 2 Verizon Political Activity January – December 2017 Political Contributions Policy: Our Voice in the Democratic Process What are the Verizon Political Action Committees? including the setting of monetary contribution limitations and The Verizon Political Action Committees (PACs) exist to help the establishment of periodic reporting requirements.