Ultrasound Guidance Does Not Improve the Results of Shock Wave for Plantar Fasciitis Or Calcific Achilles Tendinopathy: a Randomized Control Trial Masiiwa M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of the Inferior Calcaneal Spurs Influence on Plantar Fascia

Evaluation of the Inferior Calcaneal Spurs Influence on Plantar Fascia Thickness Clint Jiroux, PMS-II ; Kyle Schwickerath, PMS-II; Frank Felix, PMS-II; Chad Smith, PMS-II; Matt Greenblatt, PMS-II Arizona School of Podiatric Medicine – Midwestern University Printing: This poster is 48” wide by 36” high. It’s STATEMENT OF PURPOSE ANALYSIS & DISCUSSION designed to be printed on a large • Plantar fasciitis is a common pathology associated with plantar heel pain. It is Through ultrasound, our research revealed the spur does not show a reported that in the United States, two million patients are treated for plantar relationship to the thickness of the plantar fascia. Thus, based on our data, printer. fasciitis annually, and accounts for 15% of all foot disorders (1). A frequent diagnostic measurements of the fascia band thickness should not take into association with plantar fasciitis is the presence of an inferior calcaneal heel consideration the presence of a heel spur. This data is supportive to the spur. Often debated by medical professionals; Is the heel spur an incidental or consensus of 4mm being the diagnostic value for plantar fasciitis. Additionally, causation of plantar fasciitis (2-4)? Using ultrasound imaging, the plantar fascia this strengthens support of the heel spur being an incidental finding with plantar Figure 1. Type A inferior calcaneal spur that extends above the plantar fascia. (A) Type B inferior calcaneal Figure 2. Longitudinal ultrasound of the plantar fascia with the presence of an inferior calcaneal spur. (A) A fasciitis. thickness can be quantifiably measured to determine plantar fasciitis. An spur that extends into the plantar fascia. -

Right Ring Finger Volar Mass in a 14-Year-Old

6/6/2017 Right Ring Finger Volar Mass in a 14YearOld Boy CASE REPORT FREE Right Ring Finger Volar Mass in a 14YearOld Boy Mary P. Fox, MD; Jack E. McKay, MD; Randall D. Craver, MD; Nicholas D. Pappas, MD Orthopedics Posted May 22, 2017 DOI: 10.3928/014774472017051801 Abstract A trigger digit is relatively uncommon in adolescents and often has a different etiology in that age group vs adults. In the pediatric population, trigger digits frequently arise from a variety of underlying anatomic situations, including thickening of the flexor digitorum superficialis or flexor digitorum profundus tendons, an abnormal relationship between the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus tendons, a proximal flexor digitorum superficialis decussation, or constriction of the pulleys. In addition, underlying conditions such as mucopolysaccharidosis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, EhlersDanlos syndrome, and central nervous system disorders such as delayed motor development have been associated with triggering. Less commonly, triggering secondary to intratendinous or peritendinous calcifications or granulations has been described, which is what occurred in the current case. This report describes a case of tenosynovitis with psammomatous calcification treated with excision of the mass from the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon and release of both the A1 and palmar aponeurosis pulleys in an adolescent patient. [Orthopedics. 201x; xx(x):xx–xx.] The etiology for a trigger digit in the adolescent population can be complex and extensive, including underlying anatomic causes or other pathological processes such as fracture, tumor, or traumatic soft tissue injuries.1–5 Current literature has not described a case of tenosynovitis secondary to a peritendinous soft tissue mass consisting of psammomatous calcification in the adolescent population. -

Bioarchaeological Implications of Calcaneal Spurs in the Medieval Nubian Population of Kulubnarti

Bioarchaeological Implications of Calcaneal Spurs in the Medieval Nubian Population of Kulubnarti Lindsay Marker Department of Anthropology Primary Thesis Advisor Matthew Sponheimer, Department of Anthropology Defense Committee Members Douglas Bamforth, Department of Anthropology Patricia Sullivan, Department of English University of Colorado at Boulder April 2016 1 Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. 4 Abstract …................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1: Introduction …........................................................................................................... 8 Chapter 2: Anatomy …................................................................................................................ 11 2.1 Chapter Overview …................................................................................................. 11 2.2 Bone Composition …................................................................................................ 11 2.3 Plantar Foot Anatomy …........................................................................................... 12 2.4 Posterior Foot Anatomy …........................................................................................ 15 Chapter 3: Literature Review and Background of Calcaneal Enthesophytes ............................. 18 3.1 Chapter Overview …................................................................................................ -

The Painful Heel Comparative Study in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Ankylosing Spondylitis, Reiter's Syndrome, and Generalized Osteoarthrosis

Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.36.4.343 on 1 August 1977. Downloaded from Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 1977, 36, 343-348 The painful heel Comparative study in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter's syndrome, and generalized osteoarthrosis J. C. GERSTER, T. L. VISCHER, A. BENNANI, AND G. H. FALLET From the Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland SUMMARY This study presents the frequency of severe and mild talalgias in unselected, consecutive patients with rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter's syndrome, and generalized osteoarthosis. Achilles tendinitis and plantar fasciitis caused a severe talalgia and they were observed mainly in males with Reiter's syndrome or ankylosing spondylitis. On the other hand, sub-Achilles bursitis more frequently affected women with rheumatoid arthritis and rarely gave rise to severe talalgias. The simple calcaneal spur was associated with generalized osteoarthrosis and its frequency increased with age. This condition was not related to talalgias. Finally, clinical and radiological involvement of the subtalar and midtarsal joints were observed mainly in rheumatoid arthritis and occasionally caused apes valgoplanus. copyright. A 'painful heel' syndrome occurs at times in patients psoriasis, urethritis, conjunctivitis, or enterocolitis. with inflammatory rheumatic disease or osteo- The antigen HLA B27 was present in 29 patients arthrosis, causing significant clinical problems. Very (80%O). few studies have investigated the frequency and characteristics of this syndrome. Therefore we have RS 16 PATIENTS studied unselected groups of patients with rheuma- All of our patients had the complete triad (non- toid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), gonococcal urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis). -

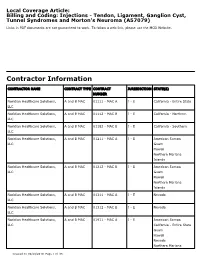

Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079)

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Created on 09/28/2019. Page 1 of 33 CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Islands Article Information General Information Original Effective Date 10/01/2019 Article ID Revision Effective Date A57079 N/A Article Title Revision Ending Date Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, N/A Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma Retirement Date N/A Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2018 American Medical Association. -

Calcific Tendinitis of the Shoulder

CME Further Education Certified Advanced Training Orthopäde 2011 [jvn]:[afp]-[alp] P. Diehl1, 2 L. Gerdesmeyer3, 4 H. Gollwitzer3 W. Sauer2 T. Tischer1 DOI 10.1007/s00132-011-1817-3 1 Orthopaedic Clinic and Polyclinic, Rostock University 2 East Munich Orthopaedic Centre, Grafing 3 Orthopaedics and Sports Orthopaedics Clinic, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Online publication date: [OnlineDate] Munich Technical University Springer-Verlag 2011 4 Oncological and Rheumatological Orthopaedics Section, Schleswig-Holstein University Clinic, Kiel Campus Editors: R. Gradinger, Munich R. Graf, Stolzalpe J. Grifka, Bad Abbach A. Meurer, Friedrichsheim Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder Abstract Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder is a process involving crystal calcium deposition in the rotator cuff tendons, which mainly affects patients between 30 and 50 years of age. The etiology is still a matter of dispute. The diagnosis is made by history and physical examination with specific attention to radiologic and sonographic evidence of calcific deposits. Patients usually describe specific radiation of the pain to the lateral proximal forearm, with tenderness even at rest and during the night. Nonoperative management including rest, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, subacromial corticosteroid injections, and shock wave therapy is still the treatment of choice. Nonoperative treatment is successful in up to 90 % of patients. When nonsurgical measures fail, surgical removal of the calcific deposit may be indicated. Arthroscopic treatment provides excellent results in more than 90 % of patients. The recovery process is very time consuming and may take up to several months in some cases. Keywords Rotator cuff Tendons Tendinitis Calcific tendinitis Calcification, pathologic English Translation oft he original article in German „Die Kalkschulter – Tendinosis calcarea“ in: Der Orthopäde 8 2011 733 This article explains the causes and development of calcific tendinitis of the shoulder, with special focus on the diagnosis of the disorder and the existing therapy options. -

Haglund's Syndrome, Retrocalaneal Exostosis

Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.820 Haglund’s Syndrome: A Commonly Seen Mysterious Condition Raju Vaishya 1 , Amit Kumar Agarwal 1 , Ahmad Tariq Azizi 2 , Vipul Vijay 1 1. Orthopaedics, Indraprastha Apollo Hospitals 2. Orthopaedics, Herat Regional Hospital, Herat, Afghanistan Corresponding author: Amit Kumar Agarwal, [email protected] Abstract Haglund’s deformity was first described by Patrick Haglund in 1927. It is also known as retrocalcaneal exostosis, Mulholland deformity, and ‘pump bump.' It is a very common clinical condition, but still poorly understood. Haglund’s deformity is an abnormality of the bone and soft tissues in the foot. An enlargement of the bony section of the heel (where the Achilles tendon is inserted) triggers this condition. The soft tissue near the back of the heel can become irritated when the large, bony lump rubs against rigid shoes. The aetiology is not well known, but some probable causes like a tight Achilles tendon, a high arch of the foot, and heredity have been suggested as causes. Middle age is the most common age of affection, females are more affected than males, and the occurence is often bilateral. A clinical feature of this condition is pain in the back of the heel, which is more after rest. Clinical evaluation and lateral radiographs of the ankle are mostly enough to make a diagnosis of Haglund’s syndrome. Haglund’s syndrome is often treated conservatively by altering the heel height in shoe wear, orthosis, physiotherapy, and anti-inflammatory drugs. Surgical excision of the bony exostoses of the calcaneum is only required in resistant cases. -

Pediatric Trigger Finger Due to Osteochondroma

HANXXX10.1177/1558944715627634HANDde Oliveira et al 627634research-article2016 Case Report HAND 1 –7 Pediatric Trigger Finger due to © American Association for Hand Surgery 2016 DOI: 10.1177/1558944715627634 Osteochondroma: A Report of Two Cases hand.sagepub.com Ricardo Kaempf de Oliveira1, Pedro J. Delgado2, and João Guilherme Brochado Geist3 Abstract Background: The trigger finger is characterized by the painful blocking of finger flexor tendons of the hand, while crossing the A1 pulley. It is a rare disease in children and, when present, is usually located in the thumb, and does not have any defined cause. Methods: We report 2 pediatric trigger finger cases affecting the long digits of the hand that were caused by an osteochondroma located at the proximal phalanx. Both children held the diagnosis of juvenile multiple osteochondromatosis. They had presented at the initial visit with a painful finger blocking. Surgical approach was decided with wide regional exposure, as compared with the trigger finger traditional surgical techniques, with the opening of the A1 pulley and the initial portion of the A2 pulley, along with bone tumor resection. Results: Patients evolved uneventfully, and recovered the affected finger motion. Conclusion: It is important to highlight that pediatric trigger finger is a distinct ailment from the adult trigger finger, and also in children is important to differentiate whenever the disease either affects the thumb or the long fingers. A secondary cause shall be sought whenever the long fingers are affected by a trigger finger. Keywords: trigger finger, pediatric, flexor tendon, bone tumor Introduction Case 1 The trigger finger, also known as stenosing tenosynovi- A 13-year-old girl who had juvenile multiple osteochondro- tis, is rare in the pediatric population and, when present, matosis (JMO) reported 18-month long complaints of left is usually located on the thumb and associated with a hand ring finger pain and snapping. -

Musculoskeletal Diagnostic Imaging

Musculoskeletal Diagnostic Imaging Vivek Kalia, MD MPH October 02, 2019 Course: Sports Medicine for the Primary Care Physician Department of Radiology University of Michigan @VivekKaliaMD [email protected] Objectives • To review anatomy of joints which commonly present for evaluation in the primary care setting • To review basic clinical features of particular musculoskeletal conditions affecting these joints • To review key imaging features of particular musculoskeletal conditions affecting these joints Outline • Joints – Shoulder – Hip • Rotator Cuff Tendinosis / • Osteoarthritis Tendinitis • (Greater) Trochanteric bursitis • Rotator Cuff Tears • Hip Abductor (Gluteal Tendon) • Adhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Tears Shoulder) • Hamstrings Tendinosis / Tears – Elbow – Knee • Lateral Epicondylitis • Osteoarthritis • Medical Epicondylitis • Popliteal / Baker’s cyst – Hand/Wrist • Meniscus Tear • Rheumatoid Arthritis • Ligament Tear • Osteoarthritis • Cartilage Wear Outline • Joints – Ankle/Foot • Osteoarthritis • Plantar Fasciitis • Spine – Degenerative Disc Disease – Wedge Compression Deformity / Fracture Shoulder Shoulder Rotator Cuff Tendinosis / Tendinitis • Rotator cuff comprised of 4 muscles/tendons: – Supraspinatus – Infraspinatus – Teres minor – Subscapularis • Theory of rotator cuff degeneration / tearing with time: – Degenerative partial-thickness tears allow superior migration of the humeral head in turn causes abrasion of the rotator cuff tendons against the undersurface of the acromion full-thickness tears may progress to -

Physiopathology of Intratendinous Calcific Deposition Francesco Oliva1, Alessio Giai Via1 and Nicola Maffulli2*

Oliva et al. BMC Medicine 2012, 10:95 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/10/95 REVIEW Open Access Physiopathology of intratendinous calcific deposition Francesco Oliva1, Alessio Giai Via1 and Nicola Maffulli2* involved tendon is the supraspinatus tendon, and in 10% Abstract of patients the condition is bilateral (Figure 1) [1]. The In calcific tendinopathy (CT), calcium deposits in the nomenclature of this condition is confusing, and, for substance of the tendon, with chronic activity-related example, in the shoulder terms such as calcific periar- pain, tenderness, localized edema and various degrees thritis, periarticular apatite deposition, and calcifying of decreased range of motion. CT is particularly tendinitis have been used [2]. We suggest to use the common in the rotator cuff, and supraspinatus, terms ‘calcific tendinopathy’,asitunderlinesthelackof Achilles and patellar tendons. The presence of calcific aclearpathogenesiswhentheprocessislocatedinthe deposits may worsen the clinical manifestations of body of tendon, and ‘insertional calcific tendinopathy’,if tendinopathy with an increase in rupture rate, slower the calcium deposit is located at the bone-tendon recovery times and a higher frequency of post- junction. operative complications. The aetiopathogenesis of CT Calcific insertional tendinopathy of the Achilles tendon is still controversial, but seems to be the result of an manifests in different patients populations, including active cell-mediated process and a localized attempt young athletes and older, sedentary and overweight indi- of the tendon to compensate the original decreased viduals [3]. Usually, radiographs evidence ossification at stiffness. Tendon healing includes many sequential the insertion of the Achilles tendon or a spur (fish-hook processes, and disturbances at different stages of osteophyte) on the superior portion of the calcaneus. -

A Systematic Review of Shockwave Therapies in Soft Tissue Conditions: Focusing on the Evidence Cathy Speed

Downloaded from http://bjsm.bmj.com/ on February 8, 2018 - Published by group.bmj.com Review A systematic review of shockwave therapies in soft tissue conditions: focusing on the evidence Cathy Speed Cambridge Centre for Health ABSTRACT other tissues.2 Many of the physical effects are and Performance, Vision Park, Background ‘Shock wave’ therapies are now considered to be dependent on the energy delivered Histon, Cambridge, UK extensively used in the treatment of musculoskeletal to a focal area. The concentrated SW energy per 2 Correspondence to injuries. This systematic review summarises the evidence unit area, the energy flux density,(EFD, in mJ/mm ), Dr Cathy Speed, base for the use of these modalities. is a term used to reflect the flow of SW energy in a Rheumatology, Sport & Methods A thorough search of the literature was perpendicular direction to the direction of propaga- Exercise Medicine, Cambridge performed to identify studies of adequate quality to tion and is taken as one of the most important Centre for Health and ‘ ’ 3 Performance, Conqueror assess the evidence base for shockwave therapies on descriptive parameters of SW dosage . There House, Vision Park, pain in specific soft tissue injuries. Both focused remains no consensus as to the definition of ‘high Cambridge CB24 9ZR, UK; extracorporeal shockwave therapy (F-ESWT) and radial and ‘low’ energy ESWT, but as a guideline, low- [email protected] pulse therapy (RPT) were examined. energy ESWT is EFD≤0.12 mJ/mm2, and high fi 2 4 Accepted 25 June 2013 Results 23 appropriate studies were identi ed. There is energy is >0.12 mJ/mm . -

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions

MEDICAL POLICY POLICY TITLE EXTRACORPOREAL SHOCK WAVE TREATMENT FOR PLANTAR FASCIITIS AND OTHER MUSCULOSKELETAL CONDITIONS POLICY NUMBER MP-2.034 Original Issue Date (Created): 7/1/2002 Most Recent Review Date (Revised): 3/23/2020 Effective Date: 6/1/2020 POLICY PRODUCT VARIATIONS DESCRIPTION/BACKGROUND RATIONALE DEFINITIONS BENEFIT VARIATIONS DISCLAIMER CODING INFORMATION REFERENCES POLICY HISTORY I. POLICY Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) using either a high- or low-dose protocol or radial ESWT, is considered investigational as a treatment of musculoskeletal conditions, including but not limited to plantar fasciitis; tendinopathies including tendinitis of the shoulder, tendinitis of the elbow (lateral epicondylitis), Achilles tendinitis and patellar tendinitis; stress fractures; avascular necrosis of the femoral head; delayed union and non-union of fractures; and spasticity. There is insufficient evidence to support a conclusion concerning the health outcomes or benefits associated with this procedure. II. PRODUCT VARIATIONS TOP This policy is only applicable to certain programs and products administered by Capital BlueCross and subject to benefit variations as discussed in Section VI. Please see additional information below. FEP PPO: Refer to FEP Medical Policy Manual MP-2.01.40, Extracorporeal Shock Wave Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions. The FEP Medical Policy Manual can be found at: https://www.fepblue.org/benefit-plans/medical-policies-and-utilization- management-guidelines/medical-policies. III. DESCRIPTION/BACKGROUND TOP CHRONIC MUSCULOSKELETAL CONDITIONS Chronic musculoskeletal conditions (e.g., tendinitis) can be associated with a substantial degree of scarring and calcium deposition. Calcium deposits may restrict motion and encroach on other structures, such as nerves and blood vessels, causing pain and decreased function.