The Guardian Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludacris – Red Light District Brothers in Arms the Pacifier

Pickwick's Video/DVD Rentals – New Arrivals 19. Sept. 2005 Marc Aurel Str. 10-12, 1010 Vienna Tel. 01-533 0182 – open daily – http://www.pickwicks.at/ __________________________________________________________________ Ludacris – Red Light District Genre: Music Synopsis: Live concert from Amsterdam plus three music videos. Brothers In Arms Genre: Action Actors: David Carradine, Kenya Moore, Gabriel Casseus, Antwon Tanner, Raymond Cruz Director: Jean-Claude La Marre Synopsis: A crew of outlaws set out to rob the town boss who murdered one of their kinsmen. Driscoll is warned so his thugs surround the outlaws and soon there is a shootout. Set in the American West. The Pacifier Genre: Comedy Actors: Vin Diesel, Lauren Graham, Faith Ford, Brittany Snow, Max Theriot, Carol Kane, Brad Gardett Director: Adam Shankman Synopsis: The story of an undercover agent who, after failing to protect an important government scientist, learns the man's family is in danger. In an effort to redeem himself, he agrees to take care of the man's children only to discover that child care is his toughest mission yet. Pickwick's Video/DVD Rentals – New Arrivals 19. Sept. 2005 Marc Aurel Str. 10-12, 1010 Vienna Tel. 01-533 0182 – open daily – http://www.pickwicks.at/ __________________________________________________________________ The Killer Language: Japanese Genre: Action Actors: Chow Yun Fat Director: John Woo Synopsis: The story of an assassin, Jeffrey Chow (aka Mickey Mouse) who takes one last job so he can retire and care for his girlfriend Jenny. When his employers betray him, he reluctantly joins forces with Inspector Lee (aka Dumbo), the cop who is pursuing him. -

Delegates Guide

Delegates Guide 9–14 March, 2018 Cultural Partners Supported by Friends of Qumra Media Partner QUMRA DELEGATES GUIDE Qumra Programming Team 5 Qumra Masters 7 Master Class Moderators 14 Qumra Project Delegates 17 Industry Delegates 57 QUMRA PROGRAMMING TEAM Fatma Al Remaihi CEO, Doha Film Institute Director, Qumra Jaser Alagha Aya Al-Blouchi Quay Chu Anthea Devotta Qumra Industry Qumra Master Classes Development Qumra Industry Senior Coordinator Senior Coordinator Executive Coordinator Youth Programmes Senior Film Workshops & Labs Coordinator Senior Coordinator Elia Suleiman Artistic Advisor, Doha Film Institute Mayar Hamdan Yassmine Hammoudi Karem Kamel Maryam Essa Al Khulaifi Qumra Shorts Coordinator Qumra Production Qumra Talks Senior Qumra Pass Senior Development Assistant Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Film Programming Senior QFF Programme Manager Hanaa Issa Coordinator Animation Producer Director of Strategy and Development Deputy Director, Qumra Meriem Mesraoua Vanessa Paradis Nina Rodriguez Alanoud Al Saiari Grants Senior Coordinator Grants Coordinator Qumra Industry Senior Qumra Pass Coordinator Coordinator Film Workshops & Labs Coordinator Wesam Said Eliza Subotowicz Rawda Al-Thani Jana Wehbe Grants Assistant Grants Senior Coordinator Film Programming Qumra Industry Senior Assistant Coordinator Khalil Benkirane Ali Khechen Jovan Marjanović Chadi Zeneddine Head of Grants Qumra Industry Industry Advisor Film Programmer Ania Wojtowicz Manager Qumra Shorts Coordinator Film Training Senior Film Workshops & Labs Senior Coordinator -

New Bfi Filmography Reveals Complete Story of Uk Film

NEW BFI FILMOGRAPHY REVEALS COMPLETE STORY OF UK FILM 1911 – 2017 filmography.bfi.org.uk | #BFIFilmography • New findings about women in UK feature film – percentage of women cast unchanged in over 100 years and less than 1% of films identified as having a majority female crew • Queen Victoria, Sherlock Holmes and James Bond most featured characters • Judi Dench is now the most prolific working female actor with the release of Victoria and Abdul this month • Michael Caine is the most prolific working actor • Kate Dickie revealed as the most credited female film actor of the current decade followed by Jodie Whittaker, the first female Doctor Who • Jim Broadbent is the most credited actor of the current decade • Brits make more films about war than sex, and more about Europe than Great Britain • MAN is the most common word in film titles • Gurinder Chadha and Sally Potter are the most prolific working female film directors and Ken Loach is the most prolific male London, Wednesday 20 September 2017 – Today the BFI launched the BFI Filmography, the world’s first complete and accurate living record of UK cinema that means everyone – from film fans and industry professionals to researchers and students – can now search and explore British film history, for free. A treasure trove of new information, the BFI Filmography is an ever-expanding record that draws on credits from over 10,000 films, from the first UK film released in cinemas in 1911 through to present day, and charts the 250,000 cast and crew behind them. There are 130 genres within the BFI Filmography, the largest of which is Drama with 3,710 films. -

Mckinney Macartney ELIZABETH TAGG WOOSTER

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd ELIZABETH TAGG WOOSTER Make Up and Hair Designer FEATURE FILMS PENELOPE Director: Mark Palansky. Producers: Jennifer Simpson, Scott Steindorff, Dylan Russell, Chris Curling, Phil Robertson and Reese Witherspoon. Starring Christina Ricci, James McAvoy and Reese Witherspoon. Stern Village / Type A / Zephyr Films. Designer Make-Up / Hair. THE HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY Director: Garth Jennings. Producers: Gary Barber, Roger Birnbaum, Nick Goldsmith, Jon Glickman and Jay Roach. Starring Martin Freeman, Mos Def, Sam Rockwell, Zooey Deschanel, Warwick Davis, Bill Nighy and Anna Chancellor. Touchstone Pictures/ Spyglass Entertainment. Designer Make-Up / Hair. WIMBLEDON Director: Richard Loncraine. Producer: Mary Richards. Executive Producers: Eric Fellner and David Livingston. Starring Kirsten Dunst and Paul Bettany. Working Title Films / Universal. Designer Make-Up / Hair. THE GATHERING Director: Brian Gilbert. Producer: Mark Samuelson. Staring Christina Ricci, Ioan Gruffudd, Stephen Dillane & Kerry Fox. Samuelson Productions / Granada Films. Designer Make-Up / Hair. LONG TIME DEAD (Pick Ups) Director: Marcus Adams. Producer: James Gay Rees. Starring Alec Newman, Joe Absolom, Lukas Haas, James Hillier and Marsha Thomason. Working Title 2 / Universal Pictures / Lola Productions. Make-Up / Hair. Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 Fax: 020 8995 2414 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 ELIZABETH TAGG WOOSTER Contd … 2 PLANET OF THE APES (UK Re-Shoots) Director: Tim Burton. Producer: Richard D Zanuck. Starring Mark Wahlberg, Tim Roth and Helena Bonham Carter. 20th Century Fox. THE BOURNE IDENTITY (Pick Ups) Director: Doug Linam. Producer: Pat Crowley. Starring Matt Damon and Franke Potente. -

Selected Academic Bibliography Career Overviews

Updated: August 2015 Sally Potter: Selected Academic Bibliography Career Overviews: Books The second, longer annotation for each of these books is quoted from: Lucy BOLTON, “Catherine Fowler, Sally Potter and Sophie Mayer, The Cinema of Sally Potter” [review] Screen 51:3 (2010), pp. 285-289. Please cite any quotation from Bolton’s review appropriately. Catherine FOWLER, Sally Potter (Contemporary Film Directors series). Chicago: University of Illinois, 2009. Fowler’s book offers an extended and detailed reading of Potter’s early performance work and Expanded Cinema events, staking a bold claim for reading the later features through the lens of the Expanded Cinema project, with its emphasis on performativity, liveness, and the deconstruction of classical asymmetric and gendered relations both on-screen and between screen and audience. Fowler offers both a career overview and a sustained close reading of individual films with particular awareness of camera movement, space, and performance as they shape the narrative opportunities that Potter newly imagines for her female characters. “By entitling the section on Potter’s evolution as a ‘Search for a “frame of her own”’, Fowler situates the director firmly in a feminist tradition. For Fowler, Potter’s films explore the tension for women between creativity and company, and Potter’s onscreen observers become ‘surrogate Sallys’ in this regard (p. 25). Fowler describes how Potter’s films engage with theory and criticism, as she deconstructs and troubles the gaze with her ‘ambivalent camera’ (p. 28), the movement of which is ‘designed to make seeing difficult’ (p. 193). For Fowler, Potter’s films have at their heart the desire to free women from the narrative conventions of patriarchal cinema, having an editing style and mise- en-scene that never objectifies or fetishizes women; rather, Fowler argues, Potter’s women are free to explore female friendships and different power relationships, uncoupled, as it were, from narratives that prescribe heterosexual union. -

Tú a Harvard Y Yo a Princenton. De La Depresión a La Esquizofrenia = You

ISSN electrónico: 1885-5210 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/rmc2020161715 TÚ A HARVARD Y YO A PRINCENTON. DE LA DEPRESIÓN A LA ESQUIZOFRENIA You to Harvard and I to Princeton. From depression to schizophrenia Mª Adolfina RUÍZ MARTÍNEZ; Sebastián PERALTA GALISTEO; Herminia CASTÁN URBANO Departamento de Farmacia y Tecnología Farmacéutica. Facultad de Farmacia. Universidad de Granada (España). e-mail: [email protected] Fecha de recepción: 5 de abril de 2019 Fecha de aceptación: 23 de mayo de 2019 Fecha de publicación: 15 de marzo de 2020 Resumen Hasta hace poco tiempo las enfermedades mentales eran tratadas como un todo, sin diferenciación alguna; las investigaciones realizadas en estos últimos años han resaltado las diferencias existentes entre algunas de ellas, de tal forma que hoy en día existen tratamientos específicos para las patologías descritas. El objetivo principal de este trabajo, es el de mostrar dos enfermedades diferentes pero que en muchos casos se confunden, depresión y esquizofrenia. Patologías que pueden tener como desencadenantes, situaciones muy diversas y que requie- ren un tratamiento farmacológico diferente. Para ello, se realizará un análisis de dos películas, Prozac Nation (2001) de Erik Skjoldbjaerg y Una mente maravillosa (2001) de Ron Howard que reflejan las vivencias reales de dos personajes; se analizará la sociedad en la que conviven y el entorno que les rodea, pero resaltando muy especialmente el apartado de la farmacoterapia, que medicamentos se utilizan, si es correcto su uso, los efectos adversos que presentan…para de esta forma poder prever si la visión de la película tiene carácter formativo en este tipo de temática. -

Katya Thomas - CV

Katya Thomas - CV CELEBRITIES adam sandler josh hartnett adrien brody julia stiles al pacino julianne moore alan rickman justin theroux alicia silverstone katherine heigl amanda peet kathleen kennedy amber heard katie holmes andie macdowell keanu reeves andy garcia keira knightley anna friel keither sunderland anthony hopkins kenneth branagh antonio banderas kevin kline ashton kutcher kit harrington berenice marlohe kylie minogue bill pullman laura linney bridget fonda leonardo dicaprio brittany murphy leslie mann cameron diaz liam neeson catherine zeta jones liev schreiber celia imrie liv tyler chad michael murray liz hurley channing tatum lynn collins chris hemsworth madeleine stowe christina ricci marc forster clint eastwood matt bomer colin firth matt damon cuba gooding jnr matthew mcconaughey daisy ridley meg ryan dame judi dench mia wasikowska daniel craig michael douglas daniel day lewis mike myers daniel denise miranda richardson deborah ann woll morgan freeman ed harris naomi watts edward burns oliver stone edward norton orlando bloom edward zwick owen wilson emily browning patrick swayze emily mortimer paul giamatti emily watson rachel griffiths eric bana rachel weisz eva mendes ralph fiennes ewan mcgregor rebel wilson famke janssen richard gere geena davis rita watson george clooney robbie williams george lucas robert carlyle goldie hawn robert de niro gwyneth paltrow robert downey junior harrison ford robin williams heath ledger roger michell heather graham rooney mara helena bonham carter rumer willis hugh grant russell crowe -

Salma, Maestra De Javier Bardem

VIERNES 28 Nogales, www.eldiariodesonora.com.mx DE FEBRERO DE 2020 Sonora, México Sección B Spielberg no dirigirá Indiana Jones 5 ›› La nueva entrega está cada vez más cerca con Harrison Ford. Sin embargo, Steven Spielberg no estará al frente de la producción. Ozzy Osbourne anuncia que sacará nuevo disco ›› Después de ser diagnosticado con Parkinson, el cantante británico no piensa retirarse de la escena musical La mexicana junto al elenco y la directora, en rueda de prensa. LONDRES, ING.- Después ráneos de él, como John de ser diagnosticado con Par- Bonham y Bon Scott, kinson, el cantante británico murieron. LE ENSEÑA HABLAR COMO MEXICANO Ozzy Osbourne no piensa re- Después de que le tirarse de la escena musical, diagnosticaron Parkinson planea crear un nuevo disco tuvo que suspender su gi- y regresar con su productor ra por Estados Unidos, lo Andrew Watt. que despertó en él la in- El exvocalista de Black quietud de crear nueva Sabbath compartió en en- música. Salma, maestra trevista con el periodis- “Tal vez no puedo es- ta Zane Lowe, en Apple tar de gira, pero puedo Music, que ha llegado a hacer música. Estoy pen- pensar en retirarse, sin sando en regresar a tra- embargó, expresó no sen- bajar con mi productor tirse en ese momento, Andrew Watt en marzo”, de Javier Bardem pues ama a sus fans. expresó. “Llegué a pensarlo. A En una entrevista rea- veces tengo pensamien- lizada con New Musical ›› La cinta The roads not taken, dirigida por la británica Sally tos locos acerca de eso, Express, el cantante ex- pero no puedo retirarme. -

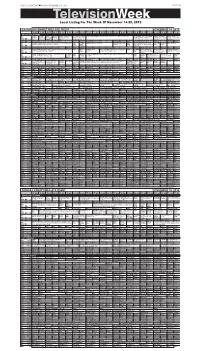

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of November 14-20, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2015 PAGE 9B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of November 14-20, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 14, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Cook’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel Songs The Lawrence Welk High School Football SDHSAA Class 11AAA, Final: Teams TBA. (N) (Live) Rock Garden Tour: Soul Butter Austin City Limits Globe Trekker The PBS Country Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd of patriotism and Show California vaca- and Hogwash (In Stereo) Å “James Taylor” (N) (In history of tea; cultural KUSD ^ 8 ^ Å Garden faith. Å tion destinations. Stereo) Å traditions. KTIV $ 4 $ College Football Wake Forest at Notre Dame. (N) Å News 4 Insider Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å Saturday Night Live News 4 Saturday Night Live (N) Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House College Football Wake Forest at Notre Dame. From Notre Dame Sta- KDLT The Big Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å Saturday Night Live KDLT Saturday Night Live Elizabeth The Simp- The Simp- KDLT News Å NBC dium in South Bend, Ind. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å News Bang (In Stereo) Å News Banks; Disclosure performs. (N) (In sons sons KDLT % 5 % (N) Å Theory (N) Å Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) College Football Michigan at Indiana. (N) (Live) Score News Edition College Football Oklahoma at Baylor. -

Women Directors in 'Global' Art Cinema: Negotiating Feminism And

Women Directors in ‘Global’ Art Cinema: Negotiating Feminism and Representation Despoina Mantziari PhD Thesis University of East Anglia School of Film, Television and Media Studies March 2014 “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Women Directors in Global Art Cinema: Negotiating Feminism and Aesthetics The thesis explores the cultural field of global art cinema as a potential space for the inscription of female authorship and feminist issues. Despite their active involvement in filmmaking, traditionally women directors have not been centralised in scholarship on art cinema. Filmmakers such as Germaine Dulac, Agnès Varda and Sally Potter, for instance, have produced significant cinematic oeuvres but due to the field's continuing phallocentricity, they have not enjoyed the critical acclaim of their male peers. Feminist scholarship has focused mainly on the study of Hollywood and although some scholars have foregrounded the work of female filmmakers in non-Hollywood contexts, the relationship between art cinema and women filmmakers has not been adequately explored. The thesis addresses this gap by focusing on art cinema. It argues that art cinema maintains a precarious balance between two contradictory positions; as a route into filmmaking for women directors allowing for political expressivity, with its emphasis on artistic freedom which creates a space for non-dominant and potentially subversive representations and themes, and as another hostile universe given its more elitist and auteurist orientation. -

Tricky Territory Creates Exciting Theatre Starring SARA BOTSFORD & TOM ORMENY

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact (for media only): Maria Gobetti, Gabriel Ormeny [email protected] (818) 841.4404 The World Premiere of The End of Sex: Tricky Territory Creates Exciting Theatre Starring SARA BOTSFORD & TOM ORMENY BURBANK, CA – March 18, 2019 – The Victory Theatre Center is proud to present the world premiere of The End of Sex (Or What’s Wrong With Mom) by Gay Walch, directed by Maria Gobetti. Opening April 26 in Burbank, this boundary-pushing new drama continues a streak of hard-hitting entertainment from the Victory Theatre. It’s Nancy’s birthday. Her daughter and son-in-law come to take the parents out to celebrate. But when new desires and old frustrations collide over dinner, all four slide into a tense standoff as Nancy questions her own collusion with the sexual agreements and power dynamics within her own marriage. Using cutting humor and venturing into tricky territory, The End of Sex (Or What’s Wrong With Mom) wrestles with how sexual behavior encourages and creates power arrangements – even in consensual relations. “As soon as I read of this play, I knew the Victory wanted to produce it,” says Gobetti. “Gay Walch has written a riveting play about an adult consensual sexual relationship. She’s investigating concerns about women colluding with their own diminishment.” Sara Botsford heads the cast with Tom Ormeny, Austin Highsmith (returning to the Victory after Resolving Hedda), Chad Coe (returning to the Victory after Resolving Hedda) and Lianna Liew. “I am excited to do The End of Sex because it takes an unflinching look at the complexities of the relations, sexual and otherwise, of consenting adults,” says Botsford. -

Download Detailseite

Panorama/IFB 2005 YES Whereas at one time he removed shrapnel from bodies, sewed up wounds Filmografie and saved lives, he now finds himself cutting up dead animals for a lavish 1979 THRILLER dinner. Nevertheless, his memories of war in the Middle East persist to this Kurzfilm YES 1983 THE GOLD DIGGERS YES day. These memories soon become their common ground – for her knowl- Kurzfilm Regie: Sally Potter edge of religious conflict in Northern Ireland means that she too is no 1986 THE LONDON STORY stranger to civil war. He lives the life of an exile in a tiny apartment – far TEARS, LAUGHTER, FEARS AND away from his culture, his family and his home. Although her surroundings RAGE may be a good deal more luxurious than his, she too lives a kind of private TV-Dokumentarserie 1988 I AM AN OX, I AM A HORSE, I AM Großbritannien/USA 2004 Darsteller exile, alone and lonely. A MAN, I AM A WOMAN Frau Joan Allen A passionate affair ensues; but all too soon their love affair is overshadowed Dokumentarfilm Länge 95 Min. Mann Simon Abkarian by events in the world at large. The religion he believed to have left behind 1992 ORLANDO (ORLANDO) Format 35 mm, 1:1.85 Anthony Sam Neill along with the world he was forced to renounce years ago, begins to take 1997 THE TANGO LESSON Farbe Putzfrau Shirley Henderson on an importance that even outweighs his need for sex and love. (TANGO LESSON) Tante Sheila Hancock 2000 THE MAN WHO CRIED Stabliste Kate Samantha Bond (IN STÜRMISCHEN ZEITEN) Buch Sally Potter Grace Stephanie Leonidas YES 2004 YES Kamera Alexei Rodionov Billy Gary Lewis C’est une Américaine originaire d’Irlande du Nord.