Ending the Constitutional Deference to Public Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

30Th Anniversary

January 2002 Vol. 27, No. 1 The Book and Paper Group: 30th Two Decades Young Anniversary ment, which has helped enlighten our col- LESLIE PAISLEY leagues in other disciplines. This is also true Inside with respect to developments in the area of n the eve of the 30th anniversary of the public service since many of our regional Continuing Education OAmerican Institute for Conservation, centers are made up primarily of BPG mem- Survey Summary the BPG specialty group reflects on its own bers specializing not only in the library and 8 past, present, and future. archives areas, but in art on paper as well. I Qualifications Task BPG members should be proud of the think that this diversity of professionalism in Force Update accomplishments and example it has set for our group—the pulling together of on-going 9 our national professional organization. In the developments in the fields of archives, words of Dianne van der Reyden,“The Book libraries, fine arts, research collections, and Annual Meeting News and Paper Group has been a role model. It is private practice—is what make our group 9 the largest specialty group in AIC and with such a strong, progressive, accomplished and FAIC Awards the high level of activity of its members, has cooperative sector of AIC.” 11 made it one of AIC’s most productive (and As BPG enters the next quarter century, forward thinking) groups. Its members— we have a strong foundation of accomplish- AIC Board Elections especially the Library and Archives areas—are ment upon which to build. 12 on the cusp of developments in the technol- Call for Posters ogy of collections management, scientific 14 research, and now in information manage- CONTINUED ON PAGE 3 In Memoriam 15 AIC Names PA and Preserving AIC’s Past Fellow Members 15 building a family or career, making a large Letter to the Editor HILARY A. -

Paradise Lost BOOK 6 John Milton (1667) the ARGUMENT Raphael

Paradise Lost BOOK 6 John Milton (1667) THE ARGUMENT Raphael continues to relate how Michael and Gabriel were sent forth to battel against Satan and his Angels. The first Fight describ'd: Satan and his Powers retire under Night: He calls a Councel, invents devilish Engines, which in the second dayes Fight put Michael and his Angels to some disorder; But, they at length pulling up Mountains overwhelm'd both the force and Machins of Satan: Yet the Tumult not so ending, God on the third day sends Messiah his Son, for whom he had reserv'd the glory of that Victory: Hee in the Power of his Father coming to the place, and causing all his Legions to stand still on either side, with his Chariot and Thunder driving into the midst of his Enemies, pursues them unable to resist towards the wall of Heaven; which opening, they leap down with horrour and confusion into the place of punishment prepar'd for them in the Deep: Messiah returns with triumph to his Father. ALL night the dreadless Angel unpursu'd Through Heav'ns wide Champain held his way, till Morn, Wak't by the circling Hours, with rosie hand Unbarr'd the gates of Light. There is a Cave Within the Mount of God, fast by his Throne, [ 5 ] Where light and darkness in perpetual round Lodge and dislodge by turns, which makes through Heav'n Grateful vicissitude, like Day and Night; Light issues forth, and at the other dore Obsequious darkness enters, till her houre [ 10 ] To veile the Heav'n, though darkness there might well Seem twilight here; and now went forth the Morn Such as in highest Heav'n, -

Edwin Kaufmann Hair and Make up Artist

Edwin Kaufmann Hair and Make up Artist Skills Hair- and make up artist Hairdresser Body make-up SFX Photographer Antonio Montani, Alfred Saerchinger, Anja Frers, Andreas Koschere, Axel Kranz, Bert Spangermacher , Birgit Bielefelds, Bob Jeusette, Daniel Woeller, Dieter Schwer, Frank Wartenberg, Gerry Ebner, Guenter, Feuerbacher, Harald Hufgad, Heli Henkel, Jens Ihnken, Jean-Luc Droux, Joerg Schifferecke, Leif Schmodde, Margaretha Olschewski, Matt Jones, Michael Leis, Michael Reh, Michael Pettersson, Marc Trautmann, Mike Azzato, Michel Comte, Neil Marriott, Nico Schmid-Burgk, Olivia Graham, Oliver Mark, Orion Dahlmann, Patrick Penkwitt, Patrick Schwalb, Peter Lidbergh, Philipp Rathmer, Tim Thiel, Thorsten Ruppert, Vlado Golub, Wilfried Bege Celebrities Aura Dione, Aloha from Hell, Britt, Backstreet Boys, Boris Becker, David Garett, Dirk Nowitzki, Die Geissens, Emily Sande, Franz Beckenbauer, Fräulein Wunder, Gabriella Cilmi, Gabrielle Strehle, Glashaus, Harald Schmidt, Jürgen Kliensmann, Jörk Pilawa, Johannes B. Kerner, Johannes Laffer, Klitschkow Brothers, Kim Wilde, Lena Meyer-Landrut, Lou Bega, Modern Talking, Mario Adorf, Nervo, No Angels, Nena, Regina Halmich, Reiner Calmund, Snap, Sabrina Settlur, Sven Väth, Steffi Graf, Verona Poth, Xavier Naidoo Clients Advertising American Express, Astra Beer, BMW, Bosch, Deutsche Bank, Dresdner Bank, Egerie, Ferrero, Ford, Gossard Lingerie, Intimates Lingerie, Lufthansa, Lidl, MTV Nestlé, Norgren, Nintento, Opel Car, Pimkie Fashion, Smart Car, Sony, Siemens, Target, Toyota, Telekom, Volkswagen -

Songs by Artist

DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist Title Versions Title Versions ! 112 Alan Jackson Life Keeps Bringin' Me Down Cupid Lovin' Her Was Easier (Than Anything I'll Ever Dance With Me Do Its Over Now +44 Peaches & Cream When Your Heart Stops Beating Right Here For You 1 Block Radius U Already Know You Got Me 112 Ft Ludacris 1 Fine Day Hot & Wet For The 1st Time 112 Ft Super Cat 1 Flew South Na Na Na My Kind Of Beautiful 12 Gauge 1 Night Only Dunkie Butt Just For Tonight 12 Stones 1 Republic Crash Mercy We Are One Say (All I Need) 18 Visions Stop & Stare Victim 1 True Voice 1910 Fruitgum Co After Your Gone Simon Says Sacred Trust 1927 1 Way Compulsory Hero Cutie Pie If I Could 1 Way Ride Thats When I Think Of You Painted Perfect 1975 10 000 Maniacs Chocol - Because The Night Chocolate Candy Everybody Wants City Like The Weather Love Me More Than This Sound These Are Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH 10 Cc 1st Class Donna Beach Baby Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz Good Morning Judge I'm Different (Clean) Im Mandy 2 Chainz & Pharrell Im Not In Love Feds Watching (Expli Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz And Drake The Things We Do For Love No Lie (Clean) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Chainz Feat. Kanye West 10 Years Birthday Song (Explicit) Beautiful 2 Evisa Through The Iris Oh La La La Wasteland 2 Live Crew 10 Years After Do Wah Diddy Diddy Id Love To Change The World 2 Pac 101 Dalmations California Love Cruella De Vil Changes 110 Dear Mama Rapture How Do You Want It 112 So Many Tears Song List Generator® Printed 2018-03-04 Page 1 of 442 Licensed to Lz0 DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Global Music Pulse: the POP CATALOG Poser's Collective

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) IIII111II1 II I 1I1II,1IIII 1I,1II1J11 III 111IJ1IInIII #BXNCCVR 3-DIGIT 908 #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 779 A06 B0128 001 033002 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT APRIL 14, 2001 COMMENTAR Y SENATE NEARING TACKLES MUSICNET PROPOSAL RAISES How To Revive INTERNET MUSIC ISSUES QUESTIONS OF FAIRNESS BY BILL HOLLAND The Senate hearing focused Singles Market BY FRANK SAXE goes into the label's pockets. WASHINGTON, D.C.-Of the many mainly on the issues of licensing NEW YORK-While the music in- Streaming media developer Real- issues presented by the 14- witness product from labels and music pub- BY MICHAEL ELLIS dustry was busy touting its new Networks is teaming with Warner panel at the Senate Judiciary Com- lishers, but no lawmakers hinted at The collapse of the U.S. sin- MusicNet digital download Music Group (WMG), mittee hearing April 3 to examine the legislation to help solve the many gles market-down more than initiative, critics were call- Inapster BMG Entertainment, growing pains marketplace 40% this year so far -is terri- ing into question the team- and the EMI Group to and problematic problems. In ble for the U.S. record indus- ing of three -fifths of the create the online sub- implications of fact, commit- try. The cause of the decline is music business into a sin- scription music service, online music, tee chairman not a lack of interest among gle entity that may one which is set to bow this lawmakers Sen. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

Natasha Bedingfield Lends Star Power As Spokesperson for EA's Boogie Superstar for Wii

Natasha Bedingfield Lends Star Power as Spokesperson for EA's Boogie SuperStar for Wii Hot Song List Revealed That Will Have Girls Cheering for More Including Hits Made Famous By The Jonas Brothers, Britney Spears, Alicia Keys, Kanye West, Katy Perry, Fall Out Boy, and Leona Lewis LOS ANGELES, Aug 27, 2008 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- The Casual Entertainment Label of Electronic Arts, Inc. (NASDAQ:ERTS) unleashes the star power behind its upcoming Boogie(TM) SuperStar game for Wii(TM) today with the announcement of international music sensation Natasha Bedingfield as the game's featured spokesperson. Additionally, EA unveils the full Boogie SuperStar soundtrack including nearly 40 hit singles made famous by today's hottest artists. Bedingfield, who has topped the Billboard charts with number one singles and albums in both the U.S. and the U.K., has joined forces with EA to promote the game, which allows girls to perform their favorite Bedingfield songs including her current single "Angel," "Love Like This," and the title track from her new hit album Pocketful of Sunshine. "Boogie SuperStar brings to life all the fun and excitement of performing," said Bedingfield. "Being on stage is such a thrill and it's great to be a part of an EA video game that lets girls experience how much fun it is to express themselves and explore their own creativity by performing." In Boogie SuperStar, players don't just play along, they are the star of the game. Girls will have a blast belting their favorite tunes into the microphone, and performing real dance moves that are captured on screen using the Wii's motion-sensing technology. -

BAYERN 3 - Der Ultimative 2000Er Countdown

BAYERN 3 - Der ultimative 2000er Countdown 1 Jahrzehnt, 2 Tage, 300 Hits - Wie gerne erinnern wir uns an Culcha Candela mit "Hamma!", an Britney Spears' "Oops, I did it again", an Nelly mit "Hot in Herre" und viele mehr. Wir versorgen euch am Rosenmontag und Faschingsdienstag (15.02./16.02.) mit dem ultimativen 2000er Countdown – hier sind eure Top 300. 300 YOU GOT THE LOVE (NEW THE SOURCE FEAT. CANDI STATON VOYAGER EDIT) 299 I DON'T WANNA KNOW MARIO WINANS 298 A THOUSAND MILES VANESSA CARLTON 297 MARIA US 5 296 ROCKSTAR NICKELBACK 295 MOVE YA BODY NINA SKY FEAT. JABBA 294 WHITE FLAG DIDO 293 DESENCHANTEE KATE RYAN 292 LA CAMISA NEGRA JUANES 291 AICHA OUTLANDISH 290 SWEET ABOUT ME GABRIELLA CILMI 289 NO ONE ALICIA KEYS 288 RELAX, TAKE IT EASY MIKA 287 TRY AGAIN AALIYAH 286 YELLOW COLDPLAY 285 HOLE IN THE HEAD SUGABABES 284 LONELY AKON 283 BLEEDING LOVE LEONA LEWIS 282 F**K YOU! CEE-LO GREEN 281 HUMAN THE KILLERS 280 I BEGIN TO WONDER J.C.A. 279 IF A SONG COULD GET ME YOU MARIT LARSEN 278 DIE LEUDE (DIE LEUTE) FÜNF STERNE DELUXE 277 ROCK DJ ROBBIE WILLIAMS 276 BUTTONS PUSSYCAT DOLLS FEAT. SNOOP DOGG 275 ONE MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 274 1234 FEIST 273 WE ARE THE PEOPLE EMPIRE OF THE SUN 272 MY HEART GOES BOOM (LA DI DA FRENCH AFFAIR DA) 271 PERFECT GENTLEMAN WYCLEF JEAN 270 FROM SARAH WITH LOVE SARAH CONNOR 269 MONSTA CULCHA CANDELA 268 IT WASN'T ME SHAGGY FEAT. RIKROK 267 CAN'T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE 266 THE SEED (2.0) THE ROOTS FEAT. -

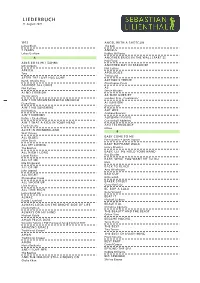

Sebastian Lilienthal

LIEDERBUCH 11. August 2021 1973 ANGEL WITH A SHOTGUN James Blunt The Cab 7 YEARS ANGELS Lukas Graham Robbie Williams A ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL [PART 2] Pink Floyd ABER BITTE MIT SAHNE Udo Jürgens ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE Phil Collins AFRICA Toto APOLOGIZE Timbaland AFTER THE LOVE HAS GONE Earth, Wind & Fire ARTHUR’S THEME Christopher Cross AGAINST ALL ODDS Phil Collins AS Stevie Wonder AI NO CORRIDA Quincy Jones AS TIME GOES BY aus dem Film „Casablanca“ AIN’T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH Diana Ross ATTENTION Charlie Puth AIN’T NO SUNSHINE Bill Withers AUF UNS Andreas Bourani AIN’T NOBODY Rufus + Chaka Khan AUTUMN LEAVES Cannonball Adderley AIN’T THAT A KICK IN YOUR HEAD Frank Sinatra AYO TECHNOLOGY Milow ALICE IN WONDERLAND B Walt Disney ALL BLUES BABY COME TO ME Miles Davis Patti Austin + James Ingram ALL MY LOVING BABY ELEPHANT WALK The Beatles Henry Mancini ALL NIGHT LONG BABY, LET ME HOLD YOUR HAND Lionel Richie Ray Charles ALL OF ME BABY, WHAT YOU WANT ME TO DO Ella Fitzgerald Elvis ALL OF ME BACK TO BLACK John Legend Amy Winehouse ALL RIGHT BAD GUY Christopher Cross Billie Eilish ALL SHOOK UP BAKER STREET Elvis Presley Gerry Rafferty ALL TIME HIGH BE-BOP-A-LULA James Bond 007 Gene Vincent ALMAZ BEAT IT Randy Crawford Michael Jackson ALWAYS LOOK ON THE BRIGHT SIDE OF LIFE BEAUTIFUL Monty Python Christina Aguilera ALWAYS ON MY MIND THE BEAUTY AND THE BEAST Michael Bublé Celine Dion AMAR PELOS DOIS BESAME MUCHO Salvador Sobral / ESC European Song Contest 2017 Tania Maria AMAZING GRACE THE BEST Traditional Gospel Tina Turner AMEN THE BEST