UK Mining Disasters 1870

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R Ed Arrow S Buses Betw Een Easington Lane, Houghton-Le

Get in touch be simpler! couldn’t with us Travelling simplygo.com the Go North East app. mobile with your to straight times and tickets Live Go North app East 0191 420 5050 0191 Call: @gonortheast Twitter: facebook.com/simplyGNE Facebook: simplygo.com/contact-us chat: web Live /redarrows 5 mins /gneapp simplygo.com Buses run up to Buses run up to 10 minutes every ramp access find You’ll bus and travel on every on board. advice safety simplygo.com smartcard. deals on exclusive with everyone, easier for cheaper and travel Makes smartcard the key /thekey the key the key X1 Go North East Bus times from 28 February 2016 28 February Bus times from Serving: Easington Lane Hetton-le-Hole Houghton-le-Spring Newbottle Row Shiney Washington Galleries Springwell Wrekenton Queen Elizabeth Hospital Gateshead Newcastle Red Arrows Arrows Red Easington Lane, Buses between Washington Houghton-le-Spring, and Newcastle Red Arrows timetable X1 — Newcastle » Gateshead » Wrekenton » Springwell » Washington Galleries » Shiney Row » Houghton-le-Spring » Hetton-le-Hole » Easington Lane Mondays to Fridays (except Public Holidays) Every 10 minutes until Service number X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1A X1 X1 X1 X1A X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 CODES C C Newcastle Eldon Square - - - 0630 0700 - 0720 0740 0800 0818 0835 0850 0905 1415 1425 1435 1445 1455 1505 1517 1527 1537 1550 1600 1610 1620 1630 1640 1650 1658 1705 1713 1720 1727 1735 1745 1755 1805 1815 1825 1840 Gateshead Interchange - - - 0639 0709 - 0730 0750 -

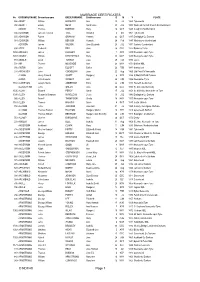

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

Indicative Layout and Capacity Study of Proposed Housing Release Sites HRS1: North of Mount Lane, Springwell Village

Core Strategy and Development Plan Indicative Layout and Capacity Study of Proposed Housing Release Sites HRS1: North of Mount Lane, Springwell Village Location SHLAA site: 407C Impact on the Green Belt: • Located on the western edge of the existing residential area of Housing release policy: HRS1 There is a moderate impact on the Green Belt if this Springwell Village site is to be removed. The site is on the urban fringe of • Lies immediately to the rear of Wordsworth Crescent and Beech Grove Owner/developer: Hellens the village and would have limited impact on urban • Lies on elevated farmland to the north of Mount Lane sprawl and countryside encroachment. Site size: 3.20 ha • Existing residential communities to the north and east • Arable land to the south and west • Close proximity to the centre of Springwell Village (which includes shops and a primary school) • Good access to the main bus route Key constraints • Bowes Railway is a Scheduled Ancient Monument (SAM) and is located to the west of the site • Springwell Ponds Local Wildlife Site (LWS) is situated to the west of the site which includes protected species. Wildlife will move through the site • The site is relatively level however the land beyond slopes southward toward Mount Lane • Development on the southern edge of the site will be subject to long distant views • Vehicle and pedestrian access to the site is restricted to one access point • Highway junction improvements will be required at Mount Lane • Development would have to ensure that additional infrastructure such as -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

Local Bus Links in Newcastle Designing a Network To

Local bus links in Newcastle Designing a network to TYNE AND WEAR meet your needs INTEGRATED TRANSPORT AUTHORITY Public consultation 15 March - 4 June 2010 Local bus links in Newcastle Designing a network to meet your needs Public consultation People in Newcastle make 47 million bus journeys annually - that’s an average of more than 173 journeys a year for every resident! Nexus, Newcastle City Council and the Tyne and Wear Integrated Transport Authority (ITA) want to make sure the network of bus services in the area meets residents’ needs. To do this, Nexus has worked together with bus companies and local councils to examine how current services operate and to look at what improvements could be made to the ‘subsidised’ services in the network, which are the ones Nexus pays for. We have called this the Accessible Bus Network Design Project (see below). We want your views on the proposals we are now making to improve bus services in Newcastle, which you can find in this document. We want to hear from you whether you rely on the bus in your daily life, use buses only occasionally or even if you don’t – but might consider doing so in the future. You’ll find details of different ways to respond on the back page of this brochure. This consultation forms part of the Tyne and Wear Integrated Transport Authority’s Bus Strategy, a three year action plan to improve all aspects of the bus services in Tyne and Wear. Copies of the Bus Strategy can be downloaded from www.nexus.org.uk/busstrategy. -

North East Gardens 2012 County Durham, Northumberland, Teesside & Tyne and Wear

North East Gardens 2012 County Durham, Northumberland, Teesside & Tyne and Wear The National Gardens Scheme www.ngs.org.uk North East County Volunteers County Organisers County Durham Shanah Smailes, The Stables, Chapman's Court, Catterick Village, North Yorkshire DL10 7UE, 01748 812887, [email protected] Northumberland and Tyne and Wear Maureen Kesteven, No. 2 Ferndene, Holburn Lane Court, Ryton NE40 3PN, 0191 4135937, [email protected] County Treasurers County Durham Gill Naisby, 44 Whitebridge Drive, Darlington DL1 3TY, 01325 381324, [email protected] Northumberland and Tyne and Wear David Oakley, [email protected] Publicity County Durham Kay Duggan, Braeside, Barningham, Richmond, North Yorkshire DL11 7DW, 01833 621455, [email protected] Northumberland and Tyne and Wear Susie White, 07941 077595, [email protected] Assistant County Organisers County Durham Elizabeth Carrick, Green House, Stone Man Lane, Gayles, nr Richmond, North Yorkshire DL11 7JB, 01833 621199 Northumberland and Tyne and Wear Patricia Fleming, Wooperton Hall, Alnwick NE66 4XS 01668 217009 Northumberland and Tyne and Wear Natasha McEwen, Fowberry Mains Farmhouse, Wooler NE71 6EN, 01668 282092 County Durham Jean Morley, The Willows, Lumley Lane,Kirkby Fleetham, North Yorkshire DL7 0SH, 01609 748066, [email protected] Cover photograph: 4 Stockley Grove Brancepeth, County Durham Photographer: Shanah Smailes Symbols at the end of each garden entry indicate features and items of special interest at the garden. hNEW Gardens opening for the first time this year or re-opening after a long break ◆ Garden also opens on non-NGS days. (Gardens which carry this symbol contribute to the NGS either by opening on a specific day(s) and/or by giving a guaranteed contribution) e Wheelchair access to at least the main features of the garden f Dogs on short leads welcome g Plants usually for sale d Garden that holds a Plant Heritage Collection a Gardens that offer accommodation. -

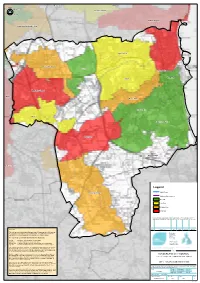

SFRA 2010 Surface Water and Sewer Map C2

Hebburn Simonside North Felling & Felling Shore Jarrow,Hedworth Heworth Seaburn & Roker Leam Lane,Wardley,Bill Quay Hylton Castle Chowdene Washington North Nissan Sheepfolds Wearmouth Pallion Washington Central Birtley Barnes Burn Hendon Burn Fatfield Ryhope & Silksworth Herrington Burdon Village Chester le Street Legend Houghton/Hetton Main Rivers Ordinary Watercourses No Risk Low Risk Medium Risk High Risk This map is reproduced from Ordinance Survey material with the permission of Ordinance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationary Office © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution of civil proceedings. Licence No. Sunderland City Council 100018385 (2009) User Notes Rev. Modifications Date Drawn Checked Approved This map has been produced using Drainage Areas GIS data supplied by NWL and has The Brew House been provided on one map for the City of Sunderland. This map shows internal and Wilderspool Park external DG5 records as supplied by NWL as a high level strategic dataset. Greenall's Avenue Warrington WA4 6HL The flood risk rating of each Drainage Area has been calculated as: United Kingdom www.jbaconsulting.co.uk No Risk No properties on internal or external register Low Risk Less than 10 properties on internal register t +44 (0)1925 437 020 Medium Risk Less than 10 properties on internal and some on external register f +44 (0)1925 437 029 High Risk Greater than 10 properties on internal and some on external register e [email protected] This map should be used to identify those locations where there may be a high number Other offices at Atherstone, Doncaster, Edinburgh, Haywards Heath, Newcastle upon Tyne, Northallerton, Northampton, Saltaire, Skipton, Tadcaster & Wallingford of historical flood records related to sewer flooding within each Drainage Area. -

COUNTY DURHAM a N 50 Gateshead L H

. D D T Scotswood W D S G E R D D ST. D O B E A W R R To — Carr N N E Nexus O W E S E B A L L A T E A L A N E M O G I Baltic HEBBURN 89 Monkton T D A TE G G Y R O O S U O O G S Jarrow and R A N Ellison O T D LAWRENCE I House R C Millennium R 88 O M S St. Anthony’s R Law T Hall A E N C Centre R K T NEW TOWN Hebburn K R A D N E Park 87 E R I A R R C W G O R R O For details of bus services E S Courts S Bridge LT M E A Park Lightfoot I E D T D N E G A 27 A N A T K E Y S O T L O D E W W N N R I A T in this area G O E E U S A L A A B A T O T K Adelaide D T T Q H N R E R S D see the C N O M O A E T T A R O HEBBURN E C E O A N ST. Y PO Newcastle guide Centre R T R D D B A S C N E Y PO G D Hebburn E E T A M B&Q L Q1 N L L S G A O D ’ ANTHONY’S I D I L S P N E V B L R O D A I T A R M D O H B S T R R R R W A O R S S N G A K Q1 93 E R O A D O E L S W I C I K S O D O E L R SAGE Q E R Newcastle W L G 94 A D U T ST. -

Bud-30 St Th 31

COLLIERY MEMORANDA , ACCIDENT [and Incident,] Bud-30 st th 31 . Dec 1814 to 19 . May 1825 A . [iii] Accidents, 3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,23,29,30,34,36,37, Air, weight of &c,18, Arch Dukes of Austria, 31, Accidents,38,39,40,43,44,46,51,52,67,68,70, B . Banks – Stop of, 15,43, Baloon, 19, Blast, Harraton, 52, Burnt, 69, [Bud-30] C . E . [iv] Coak, quality of made from Coal, 24, Cooke’s Bank Stopped, 43, Coal, consumption of in England, 90, D . F . Drowned, 37, Flood, 37, r Davy S . H., 45, Fire, 68,79, Davy Lamp, Fire art, 86, [Bud-30] G . I . [v] Gunpowder, 1, Banks – Stop of, 15,43, Gas Lights, 73, Baloon, 19, Grand Duke Michael of Russia, 84, Blast, Harraton, 52, Ditto – – – Maximilian Ditto , 91, Burnt, 69, H . K . Harraton Blast, 52, Killed, 3,4,5,6,7,9,10,15,16,23,29,30,34,36,38,39,40,43,44,46 Ditto, 51,60,63,67,70,71,72,79, Keel Wear Water, Dimensions of, 75, [Bud-30] L . N . [vi] Liege Colliery – Accident by Water, 25, Northumberland the Duke of died, 68, M . O . [Bud-30] P . R . [vii] Pitmen, Stop of, 41, Russell, Wm. Esqr., died, 68, Rainton Colly, Accident, 79, Q . S . Harraton Blast, 52, Seamen reduced to Subordination, 30, Spots on the Sun discovered, 45, Sp[ecic]gravity, 77, [Bud-30] T . W . [viii] Thermometrical observations, 47, Waggons, drawing of, Experiment, 76, V . -

Pattinson South Industrial Estate

PATTINSON SOUTH INDUSTRIAL ESTATE Washington NE38 8QD TO LET - from 1,152 sq ft LOCATION FACILITIES Washington New Town is ideally situated between the • On site parking A1 (M) and A19 providing easy access to the North East Region. Newcastle, Sunderland and Durham are within • Roller shutter doors 15 minutes drive time and Teesside is within 30 minutes. The centre is 6 miles from Sunderland and approximately 10 miles from Newcastle, with easy access from the A1 (M) / A19. The centre is located in District 8, close to the Asda Distribution Centre. DESCRIPTION TERMS The site consists of 42 self contained light industrial Please call our Asset Managers to discuss terms and units which are located on the A195. The centre is conditions. We are flexible landlords and will tailor a easily accessible direct from the A1 (M). specific package to suit your business needs EPCs available upon request Hansteen Holdings PLC is a FTSE 250 property company who are one of the largest owners of commercial property in the UK. Hansteen Asset Managers will be involved throughout the entire leasing process, from undertaking the initial viewing to agreeing terms and conditions and making sure the leasing process is an efficient experience. • Well established industrial location • Loading doors to main production area • Good access to the A1(M), A19 & A167 • Flexible terms available Misrepresentation Act 1967. These details are provided only as a general 0191 415 9415 guide to what is being offered subject to contract and subject to lease 0191 415 9415 being available and are not intended to be construed as containing any hansteen.uk.com representation of fact upon which any interested party is entitled to rely. -

Three Five Four Three Two Two One Three

Central Station Metro Bus and Metro tickets Area map and local bus services Transfare tickets Network One tickets to St James’ Park to Monument Map Key Nexus E Nearest bus stops for 9 minutes T 8 minutes R Road served by bus S Are you making one journey using Are you travelling for one day or one week on different onward travel W A A Bus stop (destinations listed below) ES R H Stop Stop no. Stop code TG E ATE C Metro bus replacement R different types of public transport types of public transport in Tyne and Wear? ø A 08NC95 twramgmp OAD GS N T G I J Metro line B 08NC94 twrgtdtw O The Journal K A HN ST N L I National Rail line C 08NC93 twramgmj R in Tyne and Wear? For one day’s unlimited travel on all public transport in Tyne Theatre D T M G National Cycle Network (off-road) D D 08NC92 twramgmg D Alt. J S E Tyne and Wear*, buy a Day Rover from the ticket machine. Hadrian’s Wall Path E 08NC91 twramgmd R Dance U Newcastle P A Transfare ticket allows you to buy just one ticket W A Gallery W Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright 2015. P ES F T 08NC90 twramgma V City IN TGA E Arts Arena T E K E R for a journey that involves travelling on more than For one week’s travel on all public transport in Tyne and Wear*, G 08NC87 twramgjt E OA L LA D Metro bus R H 08NC86 twramgjp U T simply choose which zones you need S one type of transport – eg Metro and bus. -

Meadow Well Metro Station, Newcastle

Meadow Well Metro station Bus and Metro tickets Area map and local bus services Transfare tickets Network One tickets N EW B LY ENT R N CRESC Map Key A B Norham Community M D K A A R Are you making one journey using Are you travelling for one day or one week P O Ro a d se rv ed by b us Technology L A D TO R P K R A W N E O R Directio n of travel School N O N Y T E RD C P A R L E G E L 391 M A Bus stop (destin ation s listed below) V P different types of public transport L O O T on different types of public transport in P E R A 1A G C ES S V 1 U D W Metro bus replacement E N I N S ø O L N M N D K U C H G E V I R E E 310 M L Y Metr o line A A C in Tyne and Wear? H Tyne and Wear? L St Joseph's C K ' S Y E Y A E DG W3W3 O E E UE RI E U L FORD RC Primary L L National Cycle Network N N B L E S N AV E G A P O K IN P E DA K I IC Schooll V N R W ET U A H N R North Tynes ide Stea m Railway H L N E C ᵮ A AL G D A B A E N A N A Transfare ticket allows you to buy just one ticket For one day’s unlimited travel on all public transport in V I I M E VE K O F A A A R R Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright 2013.