Togethering and Positioning: the Experience of Registered Nurses of Clinically Inflicted Pain Hannelore Gertrud Krieger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2007 LAKE KIOWA CELEBRATES the NATION’S 231ST BIRTHDAY!

PRSRT STD l U.S. POSTAGE lllll lllll PAID lll lll LAKE KIOWA PERMIT 34 l ll GAINESVILLE, TEXAS ll l 76240 l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l OMMUNI UE Lake KiowaC on the web: www.lakekiowatx.com Q Vol. 29 - No. 8 Offi cial Publication of Lake Kiowa Property Owners Association August 2007 LAKE KIOWA CELEBRATES THE NATION’S 231ST BIRTHDAY! Photos: B. Stilwell important Members of Boy Scout Troop 668 started the July 4th celebration ceremonies with the raising of the fl ag. The parade moved along without major gaps, with participants demonstrating artistry and innovation. Top right is the First Place notice Winner in the parade. The weather, although spotty at times, was most conducive to lake and beach activities. All in Corrected Petition for all, it was a tremendous day enjoyed by all. Restrictive Covenant Change Board Notes July... and 70-604 Membership What a great 4th of July celebration! Executive Chef. He was our Sous Chef resend these ballots. If you have already Election Ballot will be I heard the weather even cooperated. and has two years of Culinary School. returned your ballot, it will be voided mailed out soon. THANK YOU to all the volunteers. Jason and his wife will be moving to and the Election Committee will collect See Board Notes We owe David and Brenda Long an Lake Kiowa the fi rst of August. -

Radio & Records National Airplay

RADIO & RECORDS NATIONAL AIRPLAY MOST ADDED KENNY BURRELL/GROVER WASHINGTON (15) HOTTEST Last BOBBY HUTCHERS0N (19) Week Togethering (Blue Note) Good Bait (Landmark) STANLEY JORDAN (11) DAVID SANBORN (19) 1 0 BOBBY HUTCHERSON/Good Bait (Landmark) Magic Touch (Blue Note) Straight To The Heart (WB) 10 © STANLEY JORDAN/Magic Touch (Blue Note) D. ANGER & B. HIGBIE QUINTET (10) JAMES WILLIAMS (IS) 2 3 DAVID SANBORN/Straight To The Heart (WB) Live At Montreux (Windham Hill) Alter Ego (Sunnyside) MAYNARD FERGUSON (7) 4 o JAMES WILLIAMS/Alter Ego (Sunnyside) DAVE GRUSIN (14) Live From San Francisco (Palo Alto) One Of A Kind (GRP) 3 5 DAVE GRUSIN/One Of A Kind (GRP) RARE SILK (7) 6 O TAHIA MARIA/The Real Tania Maria: Wild! (Concord Picante) STANLEY JORDAN (14) American Eyes (Palo Alto) Magic Touch (Blue Note) 5 7 JACKSON/BROWN/WALTDN/ROKER/lt Don't Mean A Thing If You... (Pablo) 20 Q DAROL ANGER & BARBARA HIGBIE QUINTET/Live At Montreux (Windham Hill) """ER L0CKW00D GROUP "Didier Lockwood Group" (Gramavision) 8/5 17 © YELLOWJACKETS/Samurai Samba (WB) 2/1 Medium 3/2, Li9h, 1/0, Ex,ra AddS 21 To,al AdClS 5 WM0T KBEM KRVS KLCC Medium K^FM ' ' ' ' - . ^LSK, Heavy: 25 (£) KENNY BURRELL/GROVER WASHINGTON/Togethering (Blue Note) NEW PULSE JAZZ BAND "Boogis Man" (Kilmamock) 8/1 11 $ FALCON & THE SNOWMAN/Soundtrack (EMI America) Rotations: Heavy 0/0, Medium 3/0, Light 5/1, Extra Adds 0, Total Adds 1, WYBC. Medium: WFAE WMOT WNUR 8 12 BOBBY SHEW QUARTET/Breakfast Wine (Pausa) DON MENZA "Horn Of Plenty" (Pausa) 8/0 15 BILL REICHENBACH QUARTET/BIN Reichenbach Quartet (Silver Seven) KAD^KJZZ^LU ' 6/0, Li9ht 0/0' 0' TOtal AddS 0' HeaVV: WBF0, WHR0 Medium: WGBH' WBEE. -

Grover Washington, Jr. Then and Now Mp3, Flac, Wma

Grover Washington, Jr. Then And Now mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Then And Now Country: Yugoslavia Released: 1988 Style: Smooth Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1321 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1335 mb WMA version RAR size: 1777 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 403 Other Formats: MP3 DTS AAC XM MOD MP3 AU Tracklist Hide Credits Blues For D.P. A1 Bass – Ron CarterDrums – Grady Tate, Marvin "Smitty" SmithPiano – Herbie HancockSoprano Saxophone – Grover Washington, Jr. Just Enough A2 Bass – Ron CarterDrums – Marvin "Smitty" SmithPiano – Herbie HancockTenor Saxophone – Grover Washington, Jr. French Connections Drums – Darryl WashingtonElectric Bass – Gerald VeasleyGuitar – Richard Lee A3 Steacker*Percussion – Miguel FuentesPiano – James SimmonsTenor Saxophone – Grover Washington, Jr., Igor Butman* Something Borrowed, Something Blue A4 Piano – Tommy FlanaganTenor Saxophone – Grover Washington, Jr. Lullaby For Shana Bly B1 Bass – Ron CarterDrums – Marvin "Smitty" SmithPiano – Herbie HancockTenor Saxophone – Grover Washington, Jr. Stolen Moments Drums – Darryl WashingtonElectric Bass – Gerald VeasleyGuitar – Richard Lee B2 Steacker*Percussion – Miguel FuentesPiano – James SimmonsSoprano Saxophone – Grover Washington, Jr.Tenor Saxophone – Igor Butman* In A Sentimental Mood B3 Alto Saxophone – Grover Washington, Jr.Piano – Tommy Flanagan Stella By Starlight B4 Drums – Darryl WashingtonElectric Bass – Gerald VeasleyPercussion – Miguel FuentesPiano – James SimmonsSoprano Saxophone – Grover Washington, Jr.Tenor Saxophone – Igor Butman* Credits Mixed By – Grover Washington, Jr., Joe Tarsia Recorded By – Fernando Krai*, Joe Tarsia Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5099746251611 Matrix / Runout (Runout Side A): 4625161-A I HP Matrix / Runout (Runout Side B): 4625161-B I HP Other (Rights Society): SOKOJ Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Grover Washington, Then And Now (LP, CBS 462516 1 CBS CBS 462516 1 Europe 1988 Jr. -

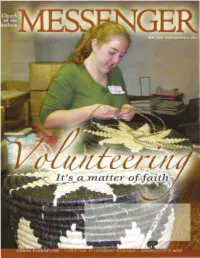

Messenger-2007-05.Pdf

Congregational Life/ Global Ministries Dinner Tuesday, July 3, 5:00-6:30 p.m. Annual Conference - Crown Plaza Ballroom, Cleveland City Center Growing the Church the Anabaptist Way A SUCCESSFUL CHURCH PLANTER SHARES HIS INSIGHTS. Speaker: Bishop Craig Sider As Bishop of the Atlantic and Southeast Conferences of the Brethren in Christ Church, Craig Sider has oversight of 86 congregations. Prior to this assignment, he served as church 1 planting pastor for 11 years in Oakville, Ontario, a suburb of Toronto. He attended Asbury Theological Seminary, Wilmore, Kentucky (M. Div). He and his wife Laura are parents of three school-aged children. Also, a special opportunity to hear the acclaimed Three Rivers Jenbe Ensemble, per/orming African singing, dancing & drumming! _J L Sponsored by: Congregational Life Ministries 7 Global Mission Partnerships ~ Church of the Brethren General Board * A ceu credit event MAY 2007 VOL.156 NO.5 WWW.BRETHREN.ORG (( . publish with the voice ef thanksgiving) and tell ef all thy wondrous work/) (Psa. 26: 7b KJV) . Editor: Walt Wiltschek Publisher: Wendy McFadden Associate Editor/News: Cheryl Brumbaugh-Cayford Promotions: Beth Burnette Subscriptions: Diane Stroyeck Design: The Concept Mill 8 Why volunteer? Every year, dozens of people offer up a year or more of their lives to serve at a Brethren Volunteer Service project. Others volunteer in more short-term ways. While many in the world are focused on getting ahead personally, why do some choose to focus instead on serving others? 12 Ministry where the rubber meets the road Wes Richard co-pastors an urban congregation in Ohio, and the unique ministry that occurs there has taught him a variety of lessons along the way. -

Sewn Together with Creativity and Purpose

FOR HOME OWNERS, HOME BUYERS, HOME DREAMERS, AND THE BUSINESSES THAT SUPPORT AND SERVE THEM | NOVEMBER 2016 REAL ESTATE MAGAZINE MENDOCINO COAST PROPERTY | LIFESTYLE | COMMUNITY Communityis Like a Quilt Volume 30 • Number 5 • Issue 691 30 • Number 5 Volume Sewn Together with Creativity and Purpose For almost a quarter-century, Mendocino Coast Children's Fund has pieced together an inclusive community "quilt" of concern and responsibility. Its actions stitch together the needs and intentions of many people of unique abilities, beliefs, and political backgrounds. Peaceful "togethering," with love and respect, for the benefit of a common cause—caring for our most vulnerable coastal children— is a model for peaceably and effectively living together. realestatemendocino.com | Find Real Events – Calendar on page 15 Page 2 Real Estate Magazine October 28, 2016 Communityis LikeB y aSara QuiltLiner Sewn Together with with Zida Borcich and Annie Liner Creativity and "Heart of Love," by Sunshine Taylor. Purpose Mixed media/collage. resources don’t stretch quite far enough to meet their needs. RESILIENCE AND COOPERATION “There’s this national narrative in the mainstream media One of the most remarkable things about living in a rural that we are a country divided by our political beliefs: left or community such as the Mendocino Coast, which is hours away right, blue or red. But our community is not defined by political from Big City resources, is that the people here come from rhetoric, it is defined by the goodwill of the people who live here, a long tradition of self-reliance. Many people still grow their and at the heart of this lies what’s most important: doing right own food, chop and stack their own wood, forage, hunt, and by our children and each other. -

Living with Animals 2: Interconnections

Living with Animals 2: Interconnections Co-organized by Robert W. Mitchell, Radhika N. Makecha, & Michał Piotr Pręgowski Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, Kentucky, 19-21 March 2015 Conference overview Locations: All talks are in the Crabbe Library, in the Grand Reading Room and Room 108. You enter the library from outside on the second floor. If you follow straight through doorways from the outside, you will eventually arrive at the Grand Reading Room, which is on the second floor. Room 108 is located on the first floor (the basement) to the left of the staircase, and the Saturday buffet lunch and poster presentations are located on the third floor. If lost, ask someone for help. Timeline: Each day begins with a keynote speaker, and follows with two tracks that run concurrently. • Thursday features the “Living with Horses” sessions, as well as concurrent sessions, and has an optional (pre-paid) trip to Berea for shopping and dinner at the Historic Boone Tavern Restaurant. • Friday features the “Teaching with Animals” sessions throughout the morning and early afternoon (which includes a boxed lunch during panel discussions and a movie showing and discussion); “Living with Animals” sessions continuing in the late afternoon, and a Conference Dinner at Masala Indian restaurant. • Saturday includes “Living with Animals” sessions throughout the day with intervening Poster Presentations during a buffet lunch. In addition, there is the optional trip to the White Hall State Historic Site (you pay when you arrive at the site). • Sunday includes an optional (pre-paid) trip to the Kentucky Horse Park. Note: Boxed lunch (Friday), conference dinner (Friday), and buffet lunch (Saturday) are included in the registration fee. -

Program and Abstracts 2016

Program and Abstracts 2016 Realizing Sustainable Futures in Socio-Ecological Systems University of Colorado Boulder, CO, USA July 24 – 30 John J. Kineman President Table of Contents Logos of Sponsors and Affiliated Organizations ............................................................................. 2 Welcome Message, Prof. John Kineman, ISSS President .............................................................. 3 Inaugural Message, Prof. Krupanidhi, Chair, Vignan ISSS Meeting ............................................... 5 Conference Schedule ...................................................................................................................... 7 Plenary Speakers .......................................................................................................................... 27 Explanation Associating Abstracts to Plenaries (Days and Topics) .............................................. 49 List of Abstracts ............................................................................................................................. 51 Plenary Speakers Abstracts .......................................................................................................... 63 Paper Session Abstracts ............................................................................................................... 69 Workshop Abstracts .................................................................................................................... 127 Poster Abstracts ......................................................................................................................... -

Toronto Arts Council Report to Economic Development Committee

Attachment TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Grants Impact Analysis ........................................................................................... 3 Summary of Increased Funding, 2013-2016, chart ……………………………………………….……. 7 Operations Budget Allocation ……………………………………………………………………………….8 Grants Programs Overview Strategic Funding .................................................................................................................. 9 Arts Discipline Funding ......................................................................................................... 10 Assessment and Allocations Process ................................................................................... 11 Loan Fund ............................................................................................................................. 11 2016 Allocations Summary ................................................................................................................ 12 Income Statement & Program Balances for the year ended December 31, 2016............................. 13 Strategic Funding 2016 Partnership Programs .......................................................................................................... 14 Strategic Partnerships ........................................................................................................... 15 Strategic Allocations .............................................................................................................. 17 Recipient Details .................................................................................................................. -

Pr Gramguide

A quarterly publication SPRING 2020 listing the programs and services pr gramof Cuyahoga County Public Library guideFREE Civic Engagement at the Library Food4Fines Reduce your library fines when you donate Super Six food items March 1 – 31. See page 1 for details. IN THIS ISSUE DEA EXHIBIT ............................. 2 – 3 A Message From Our MEET THE AUTHORS ................... 4 – 5 Executive Director BOOK DISCUSSIONS .................. 6 – 9 BUSINESS + CAREER PROGRAMS .. 10 ADULT EDUCATION PROGRAMS .... 11 Hello, WRITING PROGRAMS ................. 12 – 13 For the 10th year in a row (2010-2019), Cuyahoga STORYTIMES ............................. 14 – 15 County Public Library (CCPL) has received the highest FEATURED YOUTH PROGRAMS ..... 15 overall score in Library Journal’s Index of Public FEATURED ADULT PROGRAMS .......16 – 17 Library Service (Index). CCPL has also received the BRANCH EVENTS ........................18 – 35 Index’s prestigious five-star rating for 11 consecutive years (2009-2019). LEGEND Published annually, the Index compares U.S. W Registration Required libraries with their peers based on six per capita output measures. Ratings of five, four and three stars are awarded to libraries that generate the highest combined per capita outputs among their SPRING HOLIDAY CLOSINGS spending peers. All Cuyahoga County Public Library branches Within our peer group CCPL earned the Index’s highest overall rating, scoring 2,063 will be closed: total points, 327 points more than the next closest library system. Here’s how our per EASTER capita statistics stack up compared to America’s other large library systems: Sunday, April 12 • 1st in circulation of physical materials (e.g. books, audiobooks, DVDs, CDs) MEMORIAL DAY Sunday, May 24 & Monday, May 25 • 1st in number of visitors • 2nd in e-circulation (e.g. -

Pr Gramguide

A quarterly publication FALL 2019 listing the programs and services pr gramof Cuyahoga County Public Library guideFREE Meet Our New Executive Director IN THIS ISSUE MEET THE AUTHORS ................... 2 – 4 A Message From Our BOOK DISCUSSIONS .................. 6 – 9 Executive Director BUSINESS + CAREER PROGRAMS .. 10 ADULT EDUCATION PROGRAMS .... 11 WRITING PROGRAMS ................. 12 – 13 Hello! STORYTIMES ............................. 14 – 15 I want to take a moment to introduce myself and share FEATURED YOUTH PROGRAMS ..... 16 how honored and excited I am to be the new executive director of Cuyahoga County Public Library (CCPL). For HOMEWORK HELP ...................... 17 the past 14 years it has been a privilege to work side FEATURED ADULT PROGRAMS ....... 18 – 19 by side with former executive director Sari Feldman BRANCH EVENTS ........................ 20 – 36 as CCPL’s deputy director. I am grateful for her years of mentorship and proud of all that we accomplished LEGEND together. Sari has left behind an incredible legacy of W excellence and innovation. I am eager to work together Registration Required with library staff to continue that legacy and explore new 7 Sponsored by the Friends of the Library opportunities to serve our customers and communities. Having grown up and lived in Northeast Ohio most of my life, I bring an appreciation for the nuances of each of the 47 communities we serve. I am excited to combine that knowledge with my expertise in the breadth of services and resources CCPL offers to set a FALL HOLIDAY CLOSINGS course for the library system that will raise our standard of excellence even higher. Library All Cuyahoga County Public Library branches staff members at our 27 branches and the administrative headquarters are all focused on will be closed: exceeding your expectations, and I am grateful for and proud of the work they do every day to serve you. -

Blue Note Label Discography Was Compiled Using Our Record Collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1949 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963

Discography Of The Blue Note Label Blue Note was started in New York City in 1938 by Alfred W. Lion. Blue Note recorded jazz only. The following history of the Blue Note record label is from the Blue Note Website (bluenote.com). “In 1925, 16-year old Alfred Lion noticed a concert poster for Sam Wooding's orchestra near his favorite ice-skating arena in his native Berlin, Germany. He'd heard many of his mother's jazz records and began to take an interest in the music, but that night his life was changed. The impact of what he heard live touched a deep passion within him. His thirst for the music temporarily brought him to New York in 1928 where he worked on the docks and slept in Central Park to get closer to the music. On December 23, 1938, Lion attended the celebrated Spirituals to Swing concert at Carnegie Hall. The power, soul and beauty with which boogie woogie piano masters Albert Ammons and Meade Lux Lewis rocked the stage gripped him. Exactly two weeks later, on January 6 at 2 in the afternoon, he brought them into a New York studio to make some recordings. They took turns at the one piano, recording four solos each before relinquishing the bench to the other man. The long session ended with two stunning duets. Blue Note Records was finally a reality. The label's first brochure in May of 1939 carried a statement of purpose that Lion rarely strayed from throughout the many styles and years during which he built one of the greatest jazz record companies in the world. -

Jazz, Swing, Harmony Vocal Group & a Capella

30' - 70' - Vocal Pop ~ Show Tunes ... (easy listening, traditional pop, rhythm & blues, blues, jazz, swing, harmony vocal group & a capella 23 184 CD Allison, Mose Western man & Mose in your ear Mose Allison, Chuck Rainey, Clyde Flowers, Billy Cobham 70. léta 20. stol. 26 606 CD Andrews Sisters The Best of Andrews Sisters 30. -40. léta 20. stol. (dále viz 23126) 30 325 CD Armstrong, Louis What a wonderful world Louis Armstrong 60. léta 20. stol. (dále viz instrumentall jazz Magic moments Tom Jones, Herb Alpert, Nat King Cole, Perry Como, Dionne Warwick, 27 303 CD 3 Bacharach, Burt 60. -90. léta 20. stol. (dále viz 29337) : the definitive Burt Bacharach collection Elvis Costello, The Drifters, Manfred Mann, The Carpenters 23 367 CD 2 Bassey, Shirley Finest collection 50. -90. léta 20. stol. 23 193 CD Bassey, Shirley Let's face the music Nelson Riddle 60. léta 20. stol. 24 103 CD Belafonte, Harry The best of Harry Belafonte Harry Belafonte 70. -90. léta 20. stol. 50. -90. léta 20. stol. CD 2 Brian Bennett 22 241 Bennett, Tony The essential 10. léta 21. stol. 29 327 CD Buarque, Chico Construcao Chico Buarque, 70. léta 20. stol. 25 774 CD Clooney, Rosemary Come on-a my house : the very best of Rosemary Clooney 50. léta 20. stol. 30 428 CD Cole, Freddy Freddy Cole sings Mr. B (Billy Eckstine) Freddy Cole, 30. -90. léta 20. stol. 26 247 CD Cole, Nat King Sings the standards Nat King Cole 50. -60. léta 20. stol. 20 802 CD Cole, Nat King Portrait of Nat King Cole 40.