“Smooth Jazz” Must Be a Legitimate Genre of Jazz After All. Why? Because So Many People Are Declaring It Dead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Peter White Christmas with Rick Braun and Mindi Abair Brings the Sounds of the Season to Parker Playhouse

November 20, 2015 Media Contact: Savannah Whaley Pierson Grant Public Relations 954-776-1999 ext. 225 Jan Goodheart, Broward Center 954-765-5814 A PETER WHITE CHRISTMAS WITH RICK BRAUN AND MINDI ABAIR BRINGS THE SOUNDS OF THE SEASON TO PARKER PLAYHOUSE FORT LAUDERDALE – Celebrate the holidays with A Peter White Christmas with Rick Braun and Mindi Abair at Parker Playhouse on Saturday, December 12 at 8 p.m. One of the most versatile and prolific acoustic guitarists, White leads the contemporary jazz lineup in this seasonal concert combining smooth jazz cheer with traditional Christmas classics such as “White Christmas” and “Silent Night,” plus a few surprises along the way. White launched his career as a keyboardist touring with Al Stewart and worked with him in the studio on the classic album Year of the Cat. The tour and that album marked the beginning of a 20-year association with Stewart. During that time, the two musicians co-wrote numerous songs, including Stewart’s 1978 hit, “Time Passages.” After years as a backup musician and a session player, White launched his solo recording career and his annual Christmas tour is fueled by the success of his two highly regarded holiday albums, Songs of the Season (1997) and A Peter White Christmas (2007). Braun adds his stylistically eclectic trumpeting to the mix. A consistent chart-topper who has amassed a catalogue of #1 Billboard Contemporary Jazz Chart and radio hits throughout his solo career, Braun has also produced #1 hits for David Benoit, Marc Antoine and former Rod Stewart band sidekick Jeff Golub. -

Sponsorships

An event benefitting the AP World Organization th SEPTEMBER 11 , 2021 PerformingBOB JAMES Artists PIECES OF A DREAM GERALD ALBRIGHT JAZZ FUNK SOUL MARION MEADOWS ALEX BUGNON JEFF BRADSHAW AND FRIENDS 114 S. New York Avenue, Atlantic City, New Jersey AP WORLD An 501c-3, tax deductible organization built on the legacy of a beloved son, doing our part to strengthen families and inspire communities during difficult times. Professional basketball player, DeAndre’ Bembry of the Toronto Raptors, launched AP World in memory of his brother, Adrian Potts. Adrian celebrated his brothers’ accomplishments and planned to be sitting alongside DeAndre’ to watch the NBA draft on June 23, 2016. Adrian helped plan the draft party with their mother, Essence. Essence dedicated her life to helping her sons achieve success and was devastated when she received the dreaded phone call no parent ever wants to hear. In the early morning of June 11, 2016 literally days before the much-anticipated draft, Essence received the tragic news from Adrian’s father. Her 20-year-old, ambitious, fun-loving and tenacious son, was shot and killed near the University of North Carolina, Charlotte campus. This tragedy had a shocking and paralyzing effect on the Bembry family. Knowing where to find support and assistance while planning a funeral service, dealing with unimaginable grief and the reality of life without a son, brother and best friend, were overwhelming for Essence and DeAndre’. This family tragedy served as the catalyst for DeAndre’ to develop a support system that could be an anchor and a resource hub for other families who may have to take a similar journey through grief. -

About the Artists

Contact: Michael Caprio, 702-658-6691 [email protected] Golden Slumbers is committed to creating projects that bring families together ABOUT THE ARTISTS MICHAEL MCDONALD This five-time Grammy winner is one of the most unmistakable voices in music, singing hits for three decades. His husky soulful baritone debuted 30 years ago, famously revitalizing the Doobie Brothers with "Takin' it to the Streets," "What a Fool Believes," and "Minute by Minute”. He went onto a distinguished solo career including duets with such R&B greats as James Ingram and Patti Labelle. Michael released the Grammy nominated Motown in 2003, selling over 1.3 million copies, followed by Motown 2, released in October 2004. PHIL COLLINS One of the music industry’s rock legends, Collins played drums, sang, wrote and arranged songs, played sessions, and helped Genesis become one of the leading lights in the Progressive rock field. After numerous solo hits and Platinum-selling albums, Walt Disney studios asked him in to compose the songs to their animated feature "Tarzan," and the sin- gle, "You'll be in my Heart," was a major hit which earned him the prestigious Academy, Grammy and Golden Globe Awards. He is currently working on three new Disney projects. With a new album in the pipeline, and a continued interest in all aspects of his past, Phil Collins has proved that there is no substitute for talent. SMOKEY ROBINSON Entering his fourth decade as a singer, songwriter and producer, this velvet-voiced crooner began his career as a founding Motown executive, and frontman for the Miracles. -

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Jazz History and Research Graduate Program in Arts written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and Dr. Henry Martin And approved by Newark, New Jersey May 2016 ©2016 Zachary Streeter ALL RIGHT RESERVED ABSTRACT Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zach Streeter Thesis Director: Dr. Lewis Porter Despite the institutionalization of jazz music, and the large output of academic activity surrounding the music’s history, one is hard pressed to discover any information on the late jazz guitarist Jimmy Raney or the legacy Jimmy Raney left on the instrument. Guitar, often times, in the history of jazz has been regulated to the role of the rhythm section, if the guitar is involved at all. While the scope of the guitar throughout the history of jazz is not the subject matter of this thesis, the aim is to present, or bring to light Jimmy Raney, a jazz guitarist who I believe, while not the first, may have been among the first to pioneer and challenge these conventions. I have researched Jimmy Raney’s background, and interviewed two people who knew Jimmy Raney: his son, Jon Raney, and record producer Don Schlitten. These two individuals provide a beneficial contrast as one knew Jimmy Raney quite personally, and the other knew Jimmy Raney from a business perspective, creating a greater frame of reference when attempting to piece together Jimmy Raney. -

Beyond Classical

About the director, dean taba A highly regarded studio and freelance musician, Dean Taba began his musical studies on the piano at the age of 6 and played french horn in the Hawaii Youth Symphony. It was a desire to play in the high school jazz band that introduced him to the bass and improvised music. After extensive studies at the Berklee College of Music in Boston and a refinement of his skills on both the acoustic and electric bass, Dean relocated in 1984 to Los Angeles to HYS JAZZ become one of its most in demand musicians. Also a respected clinician and educator (Los Angeles Beyond Classical Music Academy, Musician’s Institute, Cal-Poly Pomona, Grove School of Music) Dean has recently performed/ recorded with Jeff Lorber, David Benoit, Mark Murphy, Jake Shimabukuo, Andy Summers, Sadao Watanabe, The San Francisco Symphony, Hiroshima, Rick Braun, The American Jazz Institute Orchestra, Dave Koz, Jeff Richman, Pauline Wilson, The Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra, Daniel Ho, Bill Watrous, and many others as well as playing on countless CDs, TV shows, and movie soundtracks. Take your passion and drive for music Learn more about HYS to the next level! HiYouthSymphony.org @HiYouthSymphony Hawaii Youth Symphony Open 1110 University Ave. #200 to all Honolulu, HI 96826-1598 (808) 941-9706 Students ages 14 - 18 (Grades 9 - 12) apply today! who play guitar, bass, While no prior jazz or improvisational experience is necessary, keyboards, piano, drums, admission to The Combo is by audition only. Up to 2 students sax, trumpet, trombone. of each instrument will be selected. -

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic “When Johnny Cash comes on the radio, no one changes the station. It’s a voice, a name with a soul that cuts across all boundaries and it’s a voice we all believe. Yours is a voice that speaks for the saints and the sinners – it’s like branch water for the soul. Long may you sing out. Loud.” – Tom Waits audio int‘l p. o. box 560 229 60407 frankfurt/m. germany www.audio-intl.com Catalog: IMP 6008 Format: 180-gram LP tel: 49-69-503570 mobile: 49-170-8565465 Available Spring 2011 fax: 49-69-504733 To order/preorder, please contact your favorite audiophile dealer. Jennifer Warnes, Famous Blue Raincoat. Shout-Cisco (three 200g 45rpm LPs). Joan Baez, In Concert. Vanguard-Cisco (180g LP). The 20th Anniversary reissue of Warnes’ stunning Now-iconic performances, recorded live at college renditions from the songbook of Leonard Cohen. concerts throughout 1961-62. The Cisco 45 rpm LPs define the state of the art in vinyl playback. Holly Cole, Temptation. Classic Records (LP). The distinctive Canadian songstress and her loyal Jennifer Warnes, The Hunter. combo in smoky, jazz-fired takes on the songs of Private-Cisco (200g LP). Tom Waits. Warnes’ post-Famous Blue Raincoat release that also showcases her own vivid songwriting talents in an Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Déjá Vu. exquisite performance and recording. Atlantic-Classic (200g LP). A classic: Great songs, great performances, Doc Watson, Home Again. Vanguard-Cisco great sound. The best country guitar-picker of his day plays folk ballads, bluegrass, and gospel classics. -

(Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Indie Soul Meets Jazzy Blues

Artscape Entertainment Resource Guide 2013 Band Name Genre Website Email Phone Number Allie & The Cats (Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Indie Soul meets Jazzy Blues http://www.alliemariemusic.com [email protected] 4109916973 Balti Mare Balkan Gypsy Brass http://www.facebook.com/baltimare [email protected] 4109633799 Basement Instinct (Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Alternative Rock https://www.facebook.com/basementinstinctband [email protected] 4437038941 Bearstronaut pop http://bearstronaut.com [email protected] 8609124857 Big Sur Alternative Melodic Rock http://www.bigsurrock.com [email protected] 3015931778 Billy Wilkins Jazz/Rock https://soundcloud.com/billy-wilkins-1 [email protected] 4103696360 Blizz Hip Hop http://www.hulkshare.com/Blizz [email protected] 4439860731 Boozey R&B and Hip Hop http://Boozeyonline.com [email protected] Braunsy Brooks & Worship Kulture Christian http://www.bbworshipkulture.com [email protected] 8284554010 Brittanie Thomas Music Soul/R&B http://www.brittaniethomas.com [email protected] 4433608985 Brothers Kardell Experimental electronic pop metal hip-hop http://www.soundcloud.com/brotherskardell [email protected] 2022862623 Buddah Bass Hip-Hop/Pop http://Buddahbass.bandcamp.com [email protected] 3365779559 Bumpin Uglies Reggae/Ska http://www.bumpinugliesmusic.com [email protected] 4102793613 Children of a Vivid Eden Alternative rock http://www.facebook.com/c.o.v.e.rock [email protected] 4436324130 Chris Reynolds and -

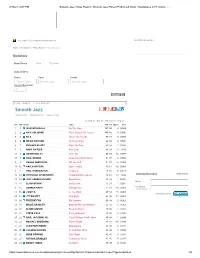

Mediabase Chart

9/30/21, 2:07 PM Smooth Jazz 7-Day Report | Smooth Jazz Panel | Published Chart | Mediabase 24/7 Charts ... … You have 92 unread Net News stories. search by keyword ... Home > Mediabase > 7-Day Report > Smooth Jazz MediabaseMediabase Song Charts Adds Stations SONG CHARTS Report Panel Format 7-Day Report Smooth Jazz Smooth Jazz Currents/Recurrents C Get Report S O N G C H A R T S : 7 - D AY R E P O R T Smooth Jazz Smooth Jazz -- Published Chart -- Currents Only lw: Sep 12 - Sep 18 TW: Sep 19 - Sep 25 lw TW Artist Title TW lw Move Aud HOT 1 1 VINCENT INGALA On The Move 107 99 8 0.089 2 2 NICK COLIONNE Right Around The Corner 100 92 8 0.095 7 3 NILS Above The Clouds 88 83 5 0.074 9 4 BRIAN SIMPSON So Many Ways 84 80 4 0.091 6 5 RICHARD ELLIOT Right On Time 83 84 -1 0.082 3 6 ANDY SNITZER Non Stop 83 88 -5 0.09 13 7 ADAM HAWLEY Risin' Up 82 68 14 0.077 10 8 PAUL BROWN Deep Into It f/Rick Braun 81 77 4 0.092 5 9 RAGAN WHITESIDE Off The Cuff 81 85 -4 0.069 14 10 KAYLA WATERS Open Portals 79 67 12 0.058 4 11 PAUL HARDCASTLE Tropicool 79 85 -6 0.073 Industry Directory quickquick searchsearch 15 12 CHRISTIAN DE MESONES Hispanica f/Bob James 75 61 14 0.06 Industry Directory 12 13 JEFF LORBER FUSION Back Room 73 72 1 0.097 Name 11 14 BLAIR BRYANT B's Bounce 72 73 -1 0.081 8 15 DARREN RAHN Midnight Sun 71 81 -10 0.069 Company or Call Letters 17 16 JIMMY B. -

Kenny G Bio 2018

A phenomenally successful instrumentalist whose recordings routinely made the pop, R&B, and jazz charts during the 1980s and ’90s, Kenny G‘s sound became a staple on adult contemporary and smooth jazz radio stations. He’s a fine player with an attractive sound (influenced a bit by Grover Washington, Jr.) who often caresses melodies, putting a lot of emotion into his solos. Because he does not improvise much (sticking mostly to predictable melody statements), his music largely falls outside of jazz. However, because he is listed at the top of “contemporary jazz” charts and is identified with jazz in the minds of the mass public, he is classified as jazz. Kenny Gorelick started playing professionally with Barry White‘s Love Unlimited Orchestra in 1976. He recorded with Cold, Bold & Together (a Seattle-based funk group) and freelanced locally. After graduating from the University of Washington, Kenny G worked with Jeff Lorber Fusion, making two albums with the group. Soon he was signed to Arista, recording his debut as a leader in 1982. His fourth album, Duotones(which included the very popular “Songbird”), made him into a star. Soon he was in demand for guest appearances on recordings of such famous singers as Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, and Natalie Cole. Kenny G’s own records have sold remarkably well, particularly Breathless, which has easily topped eight million copies in the U.S.; his total album sales top 30 million copies. The holiday album Miracles, released in 1994, and 1996’s Moment continued the momentum of his massive commercial success. He also recorded his own version of the Celine Dion/Titanic smash “My Heart Will Go On” in 1998, but the following year he released Classics in the Key of G, a collection of jazz standards like “‘Round Midnight” and “Body and Soul,” possibly to reclaim some jazz credibility. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

Album Reviews

Album Reviews I’ve written over 150 album reviews as a volunteer for CHIRPRadio.org. Here are some examples, in alphabetical order: Caetano Veloso Caetano Veloso (A Little More Blue) Polygram / 1971 Brazilian Caetano Veloso’s third self-titled album was recorded in England while in exile after being branded ‘subversive’ by the Brazilian government. Under colorful plumes of psychedelic folk, these songs are cryptic stories of an outsider and traveller, recalling both the wonder of new lands and the oppressiveness of the old. The whole album is recommended, but gems include the autobiographical “A Little More Blue” with it’s Brazilian jazz acoustic guitar, the airy flute and warm chorus of “London, London” and the somber Baroque folk of “In the Hot Sun of a Christmas Day” tells the story of tragedy told with jazzy baroque undertones of “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen.” The Clash London Calling Epic / 1979 London Calling, considered one of the greatest rock & roll albums ever recorded, is far from a straightforward: punk, reggae, ska, R&B and rockabilly all have tickets to this show of force that’s both pop and revolutionary. The title track opens with a blistering rallying cry of ska guitar and apocalypse. The post-disco “Clampdown” is a template for the next decade, a perfect mix of gloss and message. “The Guns of Brixton” is reggae-punk in that order, with rocksteady riffs and rock drums creating an intense portrait of defiance. “Train in Vain” is a harmonica puffing, Top 40 gem that stands at the crossroads of punk and rock n’ roll. -

Antelope Valley Fair Association Announces the 2Nd Annual Jazz

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Wendy Bozigian March 11, 2014 Marketing Manager 661-948-6060, ext. 132 Antelope Valley Fair Association Announces the 2nd Annual Jazz Festival Artists include: Jazz Attack (featuring Rick Braun, Euge Groove & Peter White), Jessy J, John West and local artists, The Herbie Kae & Tony Capko Band LANCASTER, CA – Officials for the Antelope Valley Fair Association announced the return of the 2nd annual Lancaster Jazz Festival scheduled for June 14, 2014. Entertainment includes Jazz Attack (featuring Rick Braun, Euge Groove and Peter White), Jessy J, John West and local art- ists, The Herbie Kae and Tony Capko Band. Tickets go on sale Tuesday, March 18th at 10am at avfair.com for $30 (general admission) and $60 and $40 (reserved seating). Parking is $5.00. The festival will open at 4pm on Saturday, June 14th, in the outdoor Cantina of the A.V. Fairgrounds and feature multiple BBQ concessions to choose from, wine tasting and other food offering unique gastronomical delights. JAZZ ATTACK - RICK BRAUN - Braun began playing music in elementary school, ultimate- ly winding up at the prestigious Eastman School of Music. Braun’s first big break came when he composed “Here With Me,” a Top 20 hit for REO Speedwagon. He's been a highly regarded pop sideman, touring and recording with the likes of Rod Stewart, War, Sade, Tina Turner, Natalie Cole, and Tom Petty. His records have ranked in the Top 10 of Billboard’s Contemporary Jazz on the R&R NAC/Smooth Jazz album charts. Braun is also an in-demand producer and has de- livered #1 radio hits with artists including David Benoit, Marc Antoine and Jeff Golub.